Two cheers for postal regulators’ move to formalize cost rules

When the last postal reform law, the Postal Accountability and Enhancement Act or PAEA, passed in 2006, it laid out three rules that work together to limit the scope of postal product offerings and prevent the Postal Service from unchecked growth into markets where competition might make it lose money.

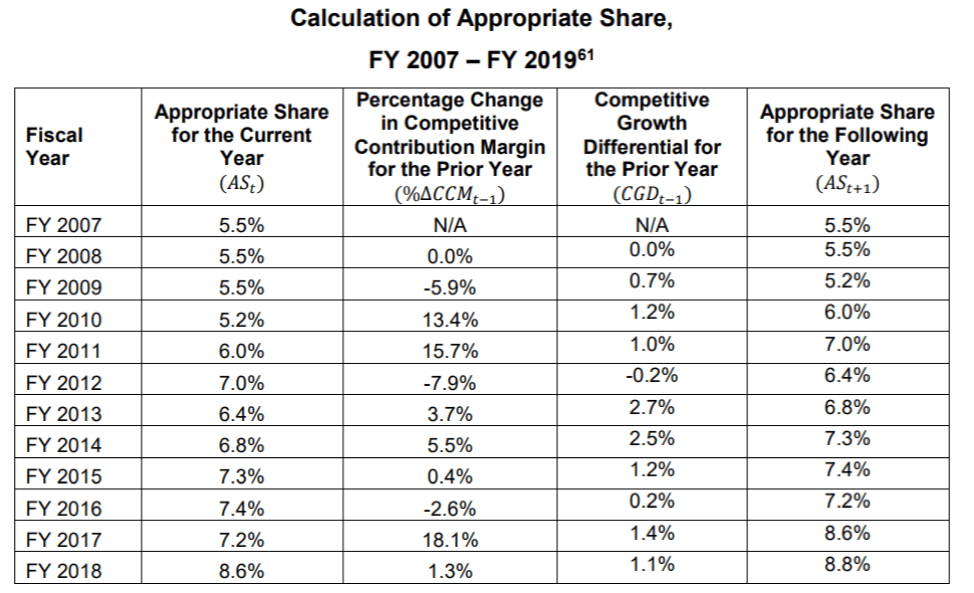

First, PAEA stipulated that competitive products can’t be subsidized by monopoly products. Second, each individual competitive product offered by USPS must earn enough to cover its attributable costs. Third, all competitive products must pay, collectively, for an appropriate share of institutional costs. Studies at the time determined that this “appropriate share” amounted to 5.5 percent of total postal costs in 2007, the first year the law was in effect. This percentage was to be reassessed every five years.

The debate over whether particular competitive postal products are being legally offered has raged for more than a decade. Accounting for whether competitive products get subsidized by monopoly products—mainly letters—gets complicated. Some argue that the existing method fails to account for all potential subsidy mechanisms. Others rely on competitive products that could lose money in the future and become unavailable, with this uncertainty adding risk to business plans. Much of the debate centers on whether the 5.5 percent of overhead costs attributable to competitive products accurately represents how much of overhead costs are incurred from parcel, express mail and other postal products.

Recently, the Postal Regulatory Commission (PRC) issued a final rule on its cost method, quantifying what previously had been a vague qualitative measure. This new approach will determine how much of postal overhead gets attributed to packages, which could effect shipping prices. Ultimately, the new cost method aims to help determine whether competitive products, like different types of parcels and express mail, are actually profitable.

In its final rule, the PRC stated clearly that it believes the 5.5 percent rate was appropriate in 2007, but that reviews should be more regular than every 5 years. The ruling makes clear that the post and parcel business is different today than it was 10 years ago. The rise of e-commerce has seen online sales triple since PAEA went into effect, with growth averaging more than 10 percent per year. At the same time, mail volumes in America have declined by about one third.

Growth that happens this fast necessitates more regular reviews of postal products to ensure that USPS only offers competitive products that are legally allowed under PAEA’s criteria. Within the post and parcel industry, ambiguity and widely divergent positions on the appropriate way to account for “fair share” rules have encouraged postal regulators to seek a permanent solution in the form of a formalized, quantitative method that allows the costs attributed to competitive products to change in line with market conditions. If USPS’ market share in parcels rises, more costs will now be attributed to competitive products, and vice versa.

By replacing what had been a fraught, qualitative test with a quantitative regulation—one that’s gone through a notice-and-comment rulemaking process—postal regulators have made the prices of USPS’ competitive products clear and predictable. The PRC’s ruling argues that the new equation successfully captures changing dynamics in the parcel business at the macro level and links costs that will be attributed to competitive products in the future to the initial 5.5 percent rate deemed appropriate in 2007. The table below illustrates how the appropriate cost share is adjusted for growth of USPS’ competitive products and its market share of the parcel business.

But this equation is imperfect. The measures used may not accurately portray the dynamics in play in the parcel business. For example, the amount of overhead caused by any particular competitive product is not considered. Rather, in this model competitive products are considered as a whole, in part because the method relies on census reports that don’t capture product-specific data. The rate at which these packages must be marked up for overhead is partially determined by the revenue share of competitive products as a whole versus other package company revenues, but only in retrospect.

This fails to account for future costs of carrying packages if, for instance, USPS must buy bulkier mail trucks than they would have to if they only delivered mail. These new costs would only be reflected in attributed costs if they caused USPS to gain market share or caused USPS package revenues to grow faster than private package companies as a whole, which is far from a sure thing. While this new quantitative method remains imperfect, it is preferable to the alternative of a fixed rate of 5.5 percent of postal costs. Even if parcels cause more than the 8.8 percent of costs that the new method projects for FY 2019, the certainty brought by the end of a long regulatory process could be a major plus in and of itself. All in all, postal regulators should be praised for taking seriously the many comments this rule drew, and developing a method that attempts to account for USPS’ unique position in the parcel industry.