How Should We Think of the OBBBA’s Electricity Subsidy Repeal?

On July 4, President Donald J. Trump signed into law the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA), which included many key changes to the subsidization and tax treatment of energy projects—most notably, a sunset of subsidies for wind and solar projects by the end of 2027. An outstanding question is what the law’s climate impact will be, given its curtailment of clean energy subsidies. While other analyses of the OBBBA detail policy changes or anticipated emission effects, this piece attempts to convey an understanding of how serious the implications might be for climate issues when these subsidies are terminated.

Will the End of Wind and Solar Subsidies Dramatically Increase Emissions?

The OBBBA makes numerous changes to energy-related subsidies, notably terminating subsidies for wind and solar projects—the largest recipients of energy subsidies—beginning in 2028. The repeal of energy-related subsidies, most of which were expanded as part of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), is projected to raise approximately $500 billion in revenue over a 10-year period. Pre-OBBBA, these subsidies were projected to cost $1.2 trillion, including $442 billion in production and investment tax credits predominantly claimed by wind and solar.

Because adding subsidies to an activity will increase it, subsidies for clean energy construction and generation increase their uptake in the market. Consequently, multiple analyses have projected that the repeal of these subsidies will result in a sharp decline in clean energy growth, with a considerable negative outcome on emissions. At R Street, we agree that the reduction of clean energy subsidies will increase emissions; however, we believe some skepticism as to the magnitude of the projected effects is warranted.

As a matter of economics, the effectiveness of a subsidy in inducing a change in the market depends upon elasticity in the affected industries and the ability of capital to induce marginal changes in activity.

A recent R Street piece explained the former point, noting that if a subsidized industry operates in a business environment where a lack of competition diminishes the need to pass on a subsidy, then the effectiveness of the subsidy in shifting activity—and especially in being passed on to product consumers—is lessened. Basically, if someone receives a subsidy to do something they would have done anyway (and if they have no competitors), then there is no additional industry growth and the only effect of the subsidy is to enrich the subsidy recipient.

The latter point on the relevance of capital in inducing additional uptake is especially important for clean energy. To understand this, consider a hypothetical: Suppose the government offered a $1,000 subsidy per person to buy a device that would make them carbon neutral, but the device itself costs $1 million. The subsidy has minimal impact in this scenario because the only people incentivized to buy the product are those willing to pay up to $999,000 (but not $1 million) out of pocket. Inversely, suppose this carbon neutral device only cost $1. What effect would the subsidy have then? Again, the additional effect would be slight—this time because the device was so cheap that people would have bought it even without the subsidy.

Analyses on the emission impacts of repealing clean energy subsidies must make assumptions about the effectiveness of subsidies in inducing market changes. Wind and solar power are already so low-cost that the effectiveness of those subsidies in inducing marginal changes in the market is likely less than what analysts are predicting—mainly due to the challenges of modeling non-capital related factors in clean energy growth. Additionally, no amount of subsidy can overcome barriers to market entry that are unrelated to cost. Notably, past R Street research has found that clean energy-related projects are more likely to encounter permitting challenges than fossil fuel projects, and surveys of wind and solar developers have found that capital constraints are the least likely reason for a project to be canceled.

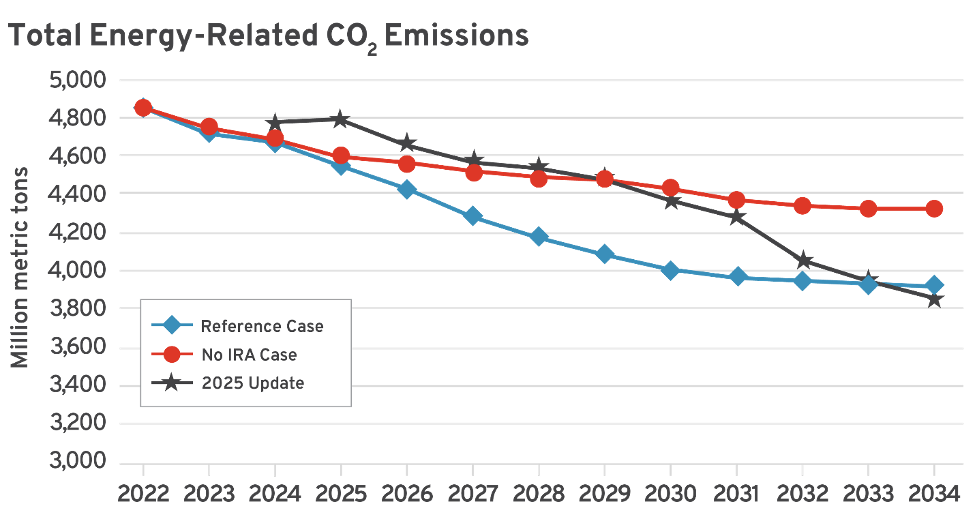

Recent R Street research reinforces these findings. Analysis of the effectiveness of IRA subsidies in inducing clean energy growth has found that current clean energy growth is far below what was anticipated to occur with the subsidies; consequently, U.S. energy-related carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions exceed projections. The following chart details projections from 2023 as to how energy subsidies from the IRA would impact emissions and compares them to the update from earlier this year.

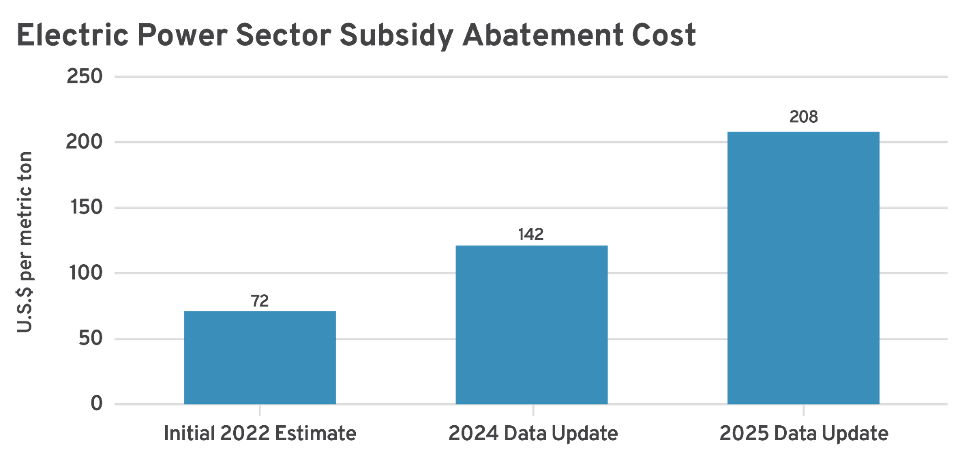

Rising abatement costs can reflect the diminishing effectiveness of clean energy subsidies in stimulating clean energy growth. The following chart demonstrates how the abatement cost of clean electricity subsidies has increased due to a combination of higher costs and less projected effect.

A conventional economics take is that subsidies for mature, cost-effective technologies like wind and solar are poor policy. Competitive energy developers already have a profit motivation to invest in these technologies where possible, and barriers to their uptake are largely due either to artificial constraints (such as permitting) or the imperfect substitutability between resources (e.g., the need to balance a portfolio of generation for when renewable energy is unavailable). Because subsidies cannot address such constraints, they have a diminishing return on effectiveness.

Overall, while it would be accurate to say we expect the repeal of wind and solar subsidies to result in higher emissions, we also believe the effectiveness of subsidies in inducing emission benefits has substantially lessened in recent years, making the policies highly inefficient. Given the inaccuracy of ex ante projections of the emission decreases from subsidy expansion in 2022, we are skeptical of similar projections regarding the effect of subsidy repeal.

A Bigger Climate Policy Picture

From an environmental perspective, and especially with an eye toward climate change, the objective is for clean energy to be a cost-effective substitute for polluting energy sources. This point on cost-effectiveness is especially important, as poorer, developing nations are the largest source of future emissions. To abate those emissions, clean energy needs to be affordable—even in areas that cannot support large government subsidies.

Analyses asserting that wind, solar, or other clean energy sources are only taken up in the United States in the presence of large subsidies ironically validate critiques of those technologies as ineffective climate solutions. If analysts projecting large emission increases from the curtailment of wind and solar subsidies are correct, then it would stand to reason that wind and solar technologies have less potential for global emission abatement than claimed.

Importantly, a careful eye toward industry characterization of electricity economics reveals this is not true. As S&P Global has noted:

Risk—not capital—is the constraint on wind and solar PV [photovoltaic] growth. A wide range of major players across the energy and finance industries have indicated no change to investment strategies—including investment in wind and solar PV—amid the dramatic change in tone from the US government, removal of climate-specific languages from websites, and select high-profile shifts, such as BP’s pivot back to fossil fuels.

This largely tracks with our understanding that considerable capital desires to invest in clean energy because it has market value even without subsidization. While we anticipate that less subsidy will consequently reduce investment, it is important to appreciate that other factors driving investment and the uptake of clean energy are still at work.

A Note About the Fiscal Picture

Past R Street work has noted that subsidies for mature technologies like wind and solar make for poor environmental policy because their high cost relative to additional environmental benefit means the policy’s social cost is almost certain to outweigh its social benefit. In lay terms, the harm to Americans from the deficit increases of wind and solar subsidies likely outweighs the potential climate benefit.

However, one cannot examine the repeal of clean energy subsidies in a vacuum. The critique of wind and solar subsidies from a fiscal responsibility perspective carries less weight in the context of the OBBBA, which utilized resultant revenues for some fiscally unwise policies while increasing deficits on net. For example, subsidies for tips or overtime will encourage employers to utilize more of those mechanisms to cover their labor costs, thereby complicating the tax code while offering no economic benefit.

Similarly, the OBBBA includes some obviously bad policies, such as the expansion of biofuel subsidies in a way that will reward environmentally damaging conventional biofuels without a discernible economic rationale. Overall, the OBBBA is expected to add $3-5 trillion to the deficit, which at some point will have to be repaid.

While we acknowledge that the OBBBA also contains many pro-growth provisions—such as making full expensing a permanent item of the tax code—from a policy perspective, we view the package as mixing some good with some bad. Consequently, deficit increases from the OBBBA may overshadow the potential economic benefits of repealing wind and solar subsidies.

Conclusion

Given the large volume of expenditure for wind and solar subsidies now slated for repeal, it makes sense that emissions will increase. But we caution against analyses that project large emission increases, as for those analyses to be correct, wind and solar technologies would have to be cost-ineffective without the subsidies—something we don’t believe to be true.