What Is Open Banking?

Authors

Media Contact

For general and media inquiries and to book our experts, please contact: pr@rstreet.org

Summary

Section 1033 of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act establishes the regulatory requirement of an open banking framework for financial institutions and their consumers. Open banking rulemaking is interpreted and implemented by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) under the Personal Financial Data Rights (PFDR) rule. Though Dodd-Frank passed in 2010, the official rulemaking governing Section 1033 has not been finalized. Rulemaking was previously established under the Biden administration, with litigation halting implementation. The CFPB subsequently rescinded the rule under the Trump administration, initiating new rulemaking under an expedited process.

Open Banking

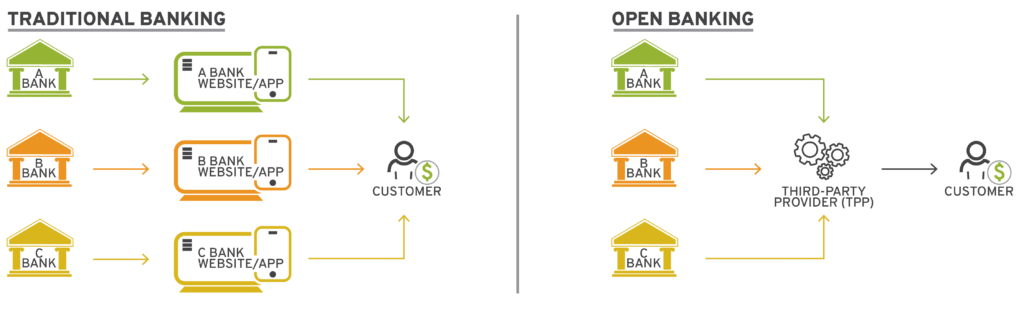

Open banking is a regulatory framework that allows consumers to securely access and share their banking information (e.g., purchase history, balance, recurring payments) with third-party financial technology providers without sharing login credentials.

Figure 1: Traditional Banking vs. Open Banking (Open Banking Drives Consumer Benefits and Choice)

Key Stakeholders

The following table shows some of the key stakeholders in open banking along with associated benefits and challenges regarding the rulemaking (which may change based on the final rule), including those related to data access fees.

| Stakeholders | Benefits | Challenges |

|---|---|---|

| Consumers | • Improved data access • Improved financial insights • More tailored recommendations and product offerings • Convenience | • Data privacy concerns • Complexity • Fragmentation |

| Consumer and Business FinTechs | • Increased customer base • Increased customer trust • More accurate data analysis | • Data access challenges, especially with smaller institutions • Regulatory risk |

| Banks/Financial Institutions | • Operational efficiency • More tailored product offerings • Customer retention and engagement via third-party integration | • Regulatory burdens • Security concerns • Competitive realignment • Liability concerns • Application programming interface (API) burden and/or unfair competitive advantage for smaller institutions |

| FinTech Data Companies | • Expanded market opportunity • More seamless data sharing • Increased demand | • Security expectations • Liability and compliance risks • Relationship management |

The Role of Technology—Including Artificial Intelligence (AI)

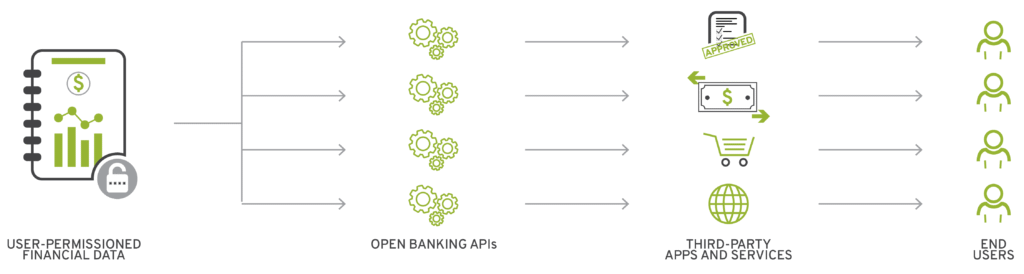

Open banking relies on secure, standardized data-sharing technologies that allow consumers to safely connect their financial accounts with third-party applications. At the center of this system is the API—a set of definitions, rules, and protocols that enable communication between two entities. In practice, APIs serve as digital “bridges” linking financial institutions to authorized third parties.

Emerging technologies like AI further strengthen this ecosystem by automating identity verification, managing user consent, and detecting anomalies that could indicate fraud or misuse. Figure 2 illustrates how these components interact across the open-banking ecosystem.

Figure 2: What Is an Open Banking API?

Real-World Example

A customer has multiple financial accounts across different institutions, including checking and investment accounts. She wants help with budgeting and determining if she can increase her allocation to meet long-term goals. She finds a trusted budgeting application that can aggregate her various accounts in one place to easily analyze and track habits.

All of her external accounts are pulled into her chosen budgeting application using APIs in conjunction with a data aggregator, which will continue to provide data securely and in real time for as long as the customer wishes. She does not need to share her credentials with the budgeting application, which creates an additional layer of privacy and security.

Key Points: The Regulatory Process and Proposed Rulemaking

“Consumer” Definition

A major point of contention in the proposed rulemaking is the technical definition of “consumer.” Section 1033 of Dodd-Frank defines a consumer as “an individual or an agent, trustee, or representative acting on behalf of an individual.” This typically would mean those with a fiduciary responsibility to the consumer, though Dodd-Frank fails to state this explicitly.

In the context of the PFDR rule, information access should be “in an electronic form usable by the consumer.” However, when paired with the current rule’s definition of “consumer,” this provision means that the permissioned data aggregators who do the heavy lifting behind the scenes would not have a right to access that information. Because individuals would be required to work with a third party in order to make any data useful, this could theoretically render the rule useless.

Conversely, including permissioned data aggregators as consumers/representatives would be a departure from typical financial regulatory definitions, broadening the term outside of those with a fiduciary duty.

Liability Framework

Who should bear responsibility if something goes wrong—the bank, the fintech, or the data aggregator? Under Section 1033, both financial institutions and authorized third parties have obligations to safeguard consumer data, yet the current rule is ambiguous regarding liability for breaches or unauthorized transactions. Many stakeholders recognize that a shared, consistent, and clearly defined liability framework would help align incentives, strengthen consumer confidence, and reduce uncertainty in enforcement.

Privacy Standards

Broader concerns surround privacy and the scope of consumer consent in open banking. Finalized under the Biden administration in 2024, the Section 1033 rule was widely criticized for exceeding the CFPB’s statutory mandate and undermining innovation and consumer privacy. By mandating that banks share sensitive financial data with third-party fintechs and aggregators without clear oversight, accountability, or baseline security requirements, the rule had the potential to increase exposure to fraud, data breaches, and unauthorized access.

Conversely, supporters of the 2024 approach maintained that the rule advanced consumers’ rights to access and control their financial information, claiming it would modernize data portability and promote innovation while also raising baseline privacy and security standards. As the CFPB reconsiders the rule, the debate has shifted toward achieving a more balanced framework.

Data Access Costs

Per the rule (as written under the Biden administration), financial institutions may not charge consumers for access to their data. However, there is no mention of costs (or lack thereof) within Section 1033. This is tightly bound to the definition of “consumer,” as charging an individual to access their own data is unreasonable as a consumer protection policy.

Conversely, it is reasonable to expect a third party to pay for access to customer data when they will ultimately profit from it. But if the definition of “consumer” includes permissioned data aggregators acting on a consumer’s behalf, then access should be free since the data is being shared at the consumer’s direction rather than for the aggregator’s independent commercial gain.

Conclusion

Section 1033 of the Dodd-Frank Act requires the CFPB to establish a regulatory framework for open banking, with the intent of allowing consumers to transfer their banking information to and among relevant parties—including fintech applications and other financial institutions—freely, seamlessly, and securely. Because the rule is under a new, abbreviated timeline for creation and implementation, relevant stakeholders have a keen interest in ensuring their needs are met with minimal regulatory burden, clear liability frameworks, and appropriate consumer protections. While these needs may compete with one another at times, rulemaking should focus on following statutory requirements and upholding consumer protections.