By the Numbers: Parsing Cybersecurity Incident and Breach Reporting Requirements

In March 2022, the U.S. Congress passed the Cyber Incident Reporting for Critical Infrastructure Act of 2022 (CIRCIA), which requires the Cybersecurity Infrastructure Security Agency to build out a new set of requirements defining how and when specified critical infrastructure entities must inform the government of a cybersecurity incident.

CIRCIA’s passage reflects the recognition that sharing timely and accurate cybersecurity threat information between the government and private sector is critical to U.S. national security. Yet the process of transitioning CIRCIA from theory to practice will likely be more contentious.

As it is, the incident reporting environment in the United States is rather crowded. Over the past several decades—particularly since 2016—a number of federally-issued cybersecurity incident and/or data breach reporting requirements have been introduced and remain in effect today. These requirements do not apply uniformly across industry, but rather are targeted at specific functions, products, sectors, or sub-sectors, and are promulgated by a variety of different federal agencies and departments.

The existing landscape of reporting requirements is both a boon and a source of frustration. On one hand, it enables overseeing authorities to micro-target some of the sectors most critical to U.S. national security and it is more developed than the reporting structures of many other peer countries. On the other hand, it leaves many sub-sectors and critical functions unaccounted for or, conversely, subjected to duplicative reporting requirements. The varied requirements make it difficult for industry, researchers and policymakers alike to parse out what already exists, where the gaps are and what compliance should look like.

These weaknesses undercut the main goal of incident reporting in the first place: to improve national security by increasing the federal government’s insight into major cyber events.

Partly to alleviate this gap, we undertook a project to chart all existing federal cyber incident and breach reporting requirements. Our research is available here. Read on for a summary of our findings and high-level takeaways.

Please note: The below graphs and analysis are based off of the total number of regulations (24) we identified. The below analysis does not include the Special Additions section of the chart. Pending or proposed requirements are also included.

The Landscape at Large

Currently, at least two dozen federally issued cybersecurity incident and/or breach reporting requirements exist. Some of these requirements apply to agencies or departments within the federal government, while others apply to the private sector. This number does not count voluntary or “suggested” reporting guidelines, but does include emergency directives and pending or proposed requirements. It also includes instances in which a federal authority offers “guidance” that is backed up by the potential for legal or regulatory action in the event of noncompliance—see, e.g. the Securities and Exchange Commission’s 2018 Guidance.

The nation’s network of sector-specific requirements differs from that of peer countries, which generally have fewer, more catch-all incident or breach reporting laws, such as Australia’s cyber incident reporting law or the European Union’s protections under the General Data Protection Regulation.

Cybersecurity Incident Reporting vs. Data Breach Disclosure

The majority of identified federal requirements pertain to cyber incident reporting rather than data-breach reporting, which differ. Roughly, an “incident” occurs when the confidentiality, integrity and availability of a digital asset or its function is compromised; a “data breach” occurs when it is confirmed that data residing on an asset or system was compromised. Both, however, require a similar reporting function and the formation of strong working relationships across industry, the U.S. government and the public.

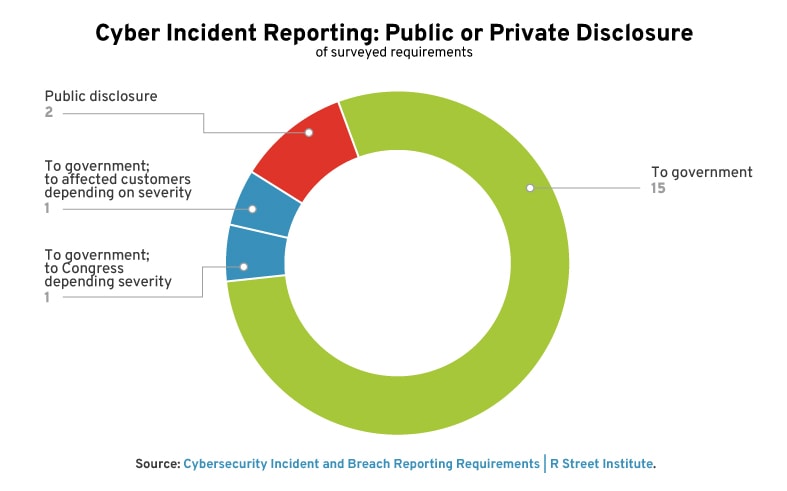

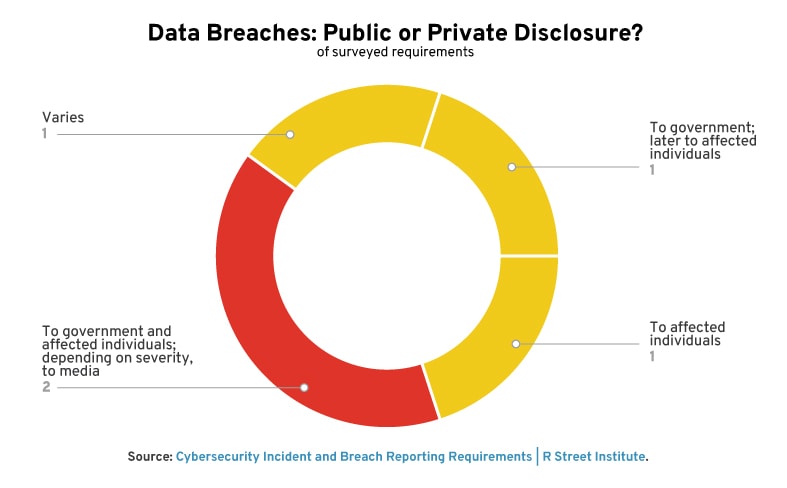

Private (Governmental) vs. Public Reporting

In the United States, there are far more instances of private reporting requirements in which disclosures are made only to the federal government and not the public. Public reporting is generally required in the case of a data breach, while private reporting is more often tied to cybersecurity incident reporting requirements. Our research suggests that public reporting is required for a cybersecurity incident in only two examples: (1) if a disruption to a banking organization is expected to last more than four hours and (2) if the affected entity is a public company regulated by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).

Data breaches require public disclosure. Sometimes, this reporting is to the impacted individual, and sometimes it is to the public at large via the media. Some requirements can escalate: for example, if more than 500 individuals are impacted under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Breach Notification rule, the individuals and the media must be notified to help spread the word.

Sector by Sector

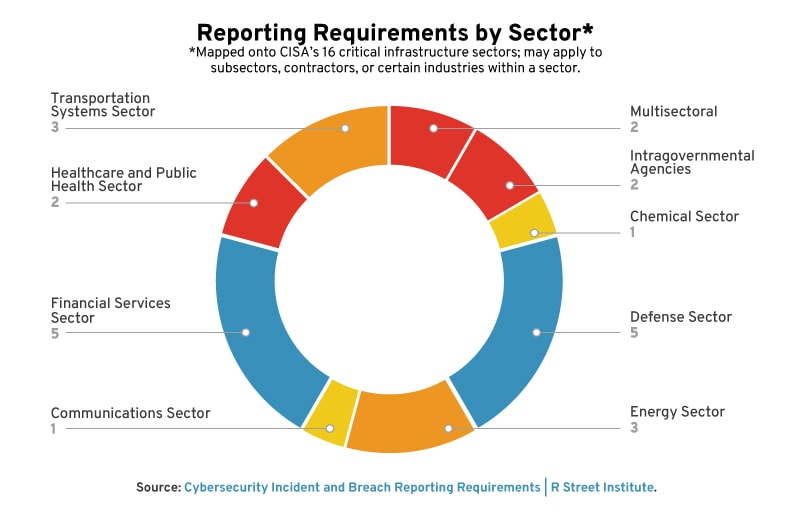

Sixteen sectors in the United States are considered “critical infrastructure.” Some of these sectors are subjected to multiple reporting requirements, while others have none at all (e.g., the water sector and waste-water treatment facilities). A sector may have reporting requirements that apply to only some entities within that sector (e.g., although healthcare has a number of requirements for reporting, medical device compromises are not included).

Often, requirements within a single sector are split under different authorities based on the entity or incident type. For example, hospitals and health care providers covered under HIPAA must report data breaches to the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). However, the loss of personal health records must be reported to the Federal Trade Commission (FTC). Thus, healthcare entities sometimes report breaches to the HHS, sometimes to the FTC and sometimes to both.

As seen below, the greatest number of individual surveyed rules apply to the financial and defense sectors. The health, energy and transportation sectors follow behind. More rules do not necessarily equal “better” cybersecurity policy—but they certainly do increase the level of complexity in navigating reporting requirements.

Reporting Timelines

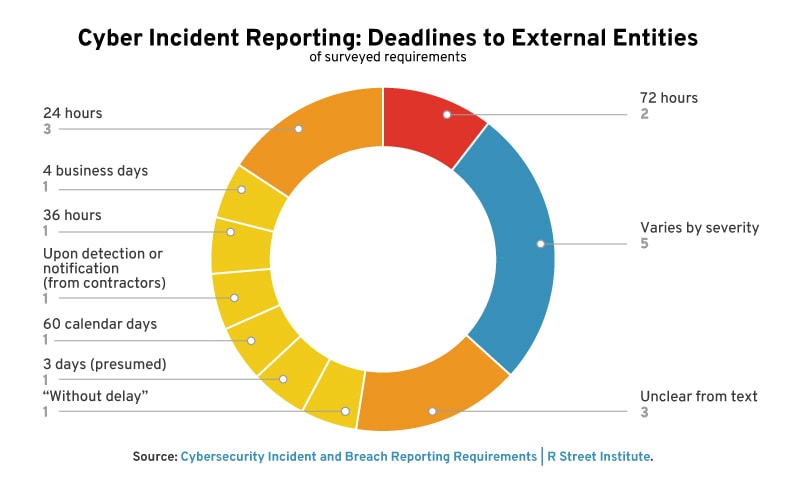

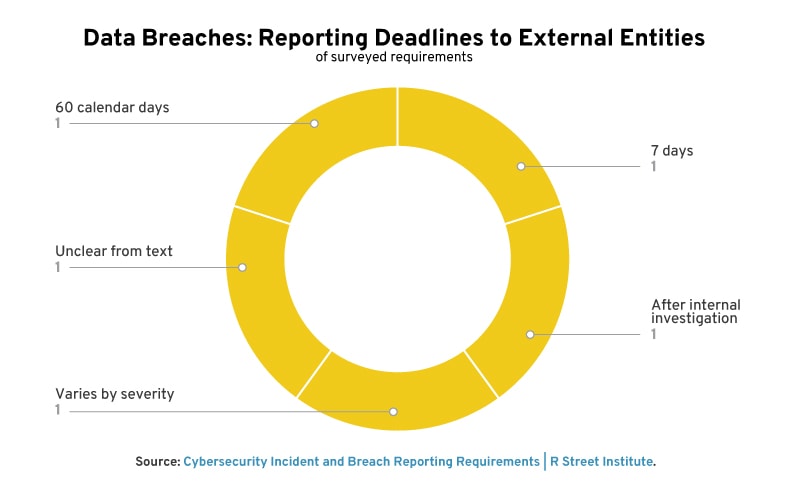

Reporting timelines range substantially in duration. Generally, incident reporting timelines are shorter than data breach timelines.

Some requirements have timelines that vary based on severity. Electric utilities reporting an attempted compromise under the Department of Energy’s form OE-417 have either 1 hour, 6 hours, or the end of the next calendar day.

Frequently, requirements decline to specify an exact deadline, offering instead phrases such as “without unreasonable delay,” “rapidly,” or “as soon as possible.” This offers some flexibility to reporting entities, but brings obvious shortcomings: difficulty of enforcement, general vagueness, etc. On the other hand, when timelines are defined—particularly when they are short—there is concern that there is insufficient time to understand the threat at hand before being forced to disclose.

Notably, public reporting can often be delayed for law enforcement or national security reasons, as in the case of FTC’s health breach notification rule. Currently, there does not appear to be a national security exemption for public reporting in the proposed SEC rulemaking (2022).

Implementing Agencies and Regulators

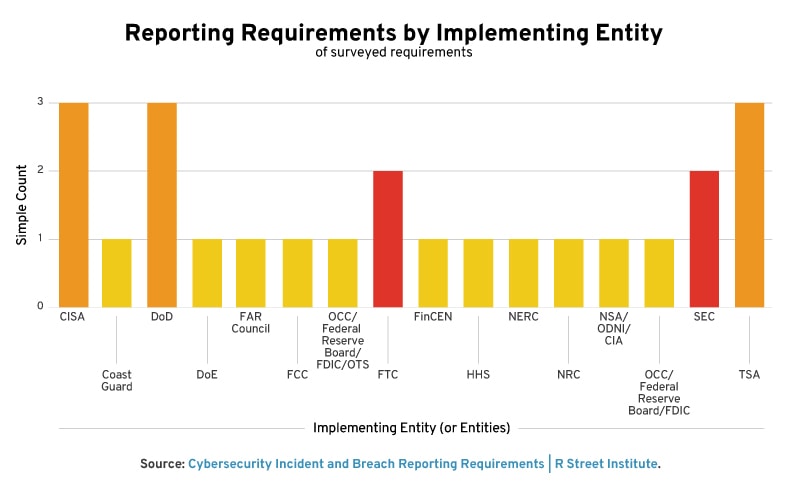

According to our findings, over a dozen different entities directly implement or otherwise oversee specific federal cybersecurity incident and breach reporting requirements. Some of these are the traditional security agencies or the designated sector risk management agency for a given sector, such as the Cybersecurity and Information Security Agency (CISA) of the Department of Homeland Security or the Department of Defense. Many others are sector or sub-sector-specific like the Federal Communications Council, which regulates carriers and providers, or the North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC), which regulates bulk power systems.

Sometimes a lead agency handles the issue area on its own; other times, it splits the work among other entities with similar or complementary jurisdictions. For example, banking institutions are required to report pursuant to a joint rulemaking by the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation.

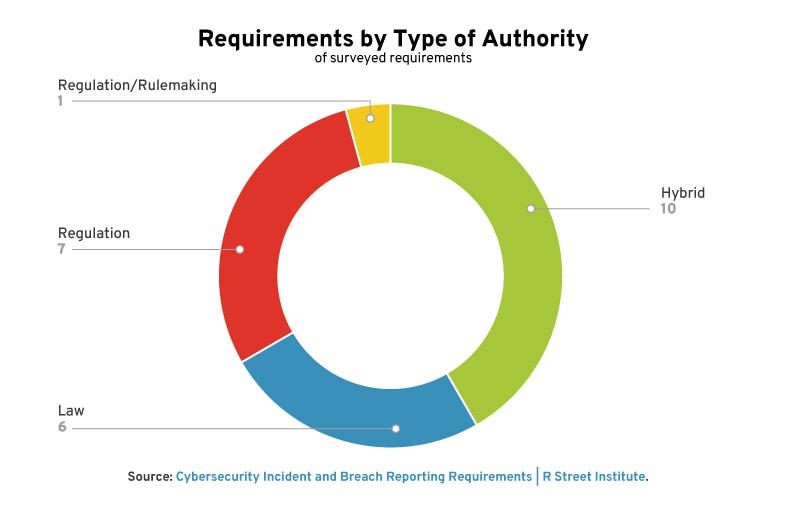

Requirements are sometimes issued following the passage of a specific law by Congress, as is the case with CIRCIA and the Federal Information Security Modernization Act of 2014. Other times, Executive Orders are used to issue new requirements for federal agencies or departments, including two new ones issued by President Joe Biden: One directed at the security of executive branch entities broadly and one directed at the security agencies.

However, a number of requirements are issued as regulations or rules by a federal agency within its own, often preexisting, rulemaking authority. Consider, for example, last year’s promulgation of new pipeline security requirements via emergency directives by the Transportation Safety Administration or the Coast Guard’s authority to issue rules to ports that guarantee maritime safety and security.

Most requirements apply statutorily—that is, to all designated entities within a sector or those that provide a certain product. The major exception is the Department of Defense’s contractually-imposed requirements (e.g. the Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement (DFARS) Clause 252.204-7012), which obligate companies to report—who otherwise would not have to do so—if they supply the defense industrial base under contract with the U.S. government.

Updates and Revisions

It is not uncommon for requirements to be rooted in older pieces of legislation and to be amended or interpreted more broadly over time.

A prominent example is the original HIPAA, which broadly called for security practices to protect information against intrusion. The law was updated by the HITECH Act, which required the Department of Health and Human Services to issue specific regulations around breach reporting. The result of this update was the HIPAA Breach Notification rule. Similarly, the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act and the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act expanded upon existing rules in the financial and health industries, respectively.

In Conclusion

The current cybersecurity incident and breach reporting landscape in the United States is dynamic and highly fragmented, which is an approach that reflects the history of its evolution and the federalized nature of the U.S. government, as much as any overall security aim.

Over the course of the next few years, and particularly as CIRCIA is developed, this landscape is likely to undergo substantial transformation. Ideally, of course, any new regulations will be designed to alleviate regulatory complexity while eliminating duplicative requirements or gaps in coverage.

However, throughout this process, it’s important to retain sight of the bigger picture: The United States government’s risk assessment has fundamentally changed. Whereas, just over a decade ago, the government was content to let industry voluntarily share data and set its own security standards, today it has realized that this stance is no longer sufficient. A stronger, more explicitly defined reporting relationship is mandatory.

Yet at the same time, for all the importance of the federal government’s role, policymakers cannot forget that it is industry that is at the forefront of national security efforts in cyberspace. It is the private sector that owns, operates and bears responsibility for a substantial portion of U.S. critical infrastructure. As such, a fully-developed incident and breach reporting system, and a matured CIRCIA, is one that makes industry compliance as easy and efficacious as possible, all in the service of broader national security goals.