Transportation Network Company Insurance: Problems and Solutions

Author

Table of Contents

- Executive Summary

- Part 1: TNCs Face Challenges on Many Fronts

- Part 2: Insurance and Public Policy Solutions to TNC Issues

- UM/UIM History – Addendum 1

- Tough to Make a Buck in Commercial Auto – Addendum 2

- Conclusion

Media Contact

For general and media inquiries and to book our experts, please contact: pr@rstreet.org

Executive Summary

Insurance exposures, trends, and solutions for the transportation network company (TNC) sector are influenced by numerous factors. Many of these factors are similar to insurance challenges faced by private passenger automobile (PPA) and commercial automobile insurance. In some cases, however, loss severity for TNCs is significantly higher than that of PPA and more akin to elevated loss severity trends seen at commercial auto insurers. Factors impacting TNC insurance trends explored in this study include:

- Social inflation

- High attorney representation rates

- Long claim payment patterns

- High loss severity compared to non-TNC losses

- High limits

- Phantom damages, paid versus incurred discrepancy, excessive utilization

- Overall high insurance costs

- Claims fraud

The combined impact of these TNC loss drivers has created challenges for ratemaking—challenges exacerbated by the novelty of the TNC business model and the absence of historical loss data to inform pricing and reserving practices appropriately. In this study, we explore each of these loss drivers and their impact on TNC insurance results.

Our study also presents recommended avenues to reduce some of the volatility in results and to lay the foundation for risk-adjusted rates for the TNC industry. Lower volatility in results is beneficial for TNC drivers, their customers, insurers, and their shareholders. Our recommendations include:

- Introduce lower limits of insurance

- Overturn the collateral source rule

- Call out phantom damage abuse

- Implement the Maryland model

- Pursue an occupational accident insurance alternative

- Slow down runners and ambulance chasers

In the addenda, we provide case studies of unintended consequences that emerged following efforts to reduce automobile insurance litigation by introducing no-fault and uninsured/underinsured motorist (UM/UIM) coverage. The addenda also describe the challenging conditions in commercial auto insurance, a line of business that shares some of the same challenges as TNCs.

Introduction

The burgeoning transportation network company (TNC) and the broader sharing sector has ushered large firms with novel business models into the economy. These include Uber, Airbnb, DoorDash, and Lyft, four companies with approximately $350 billion in market capitalization. The emergence of such firms highlights the need for new insurance products designed to cover their unique exposures.

It has been 15 years since Uber was launched in San Francisco in 2009, with Lyft following three years later. Early challenges with insurance for TNCs may have been growing pains; yet, some pain points continue.

Early challenges in providing coverage for TNCs included crafting policy wording such that the commercial-use exclusion in conventional private passenger automobile (PPA) policy forms could be replaced by wording that provided commercial use cover. For example, because TNC drivers are not covered by their PPA policy—from the time they are available to accept rides in the TNC application (app) until the driver logs off—the TNC is exposed to a variety of automobile-related risks. These include:

- Third-party automobile liability

- Uninsured and underinsured motorists’ (UM/UIM) liability

- Auto physical damage

- Personal injury protection

In addition to PPA-related exposures, TNCs are exposed to numerous other insurable risks, including:

- Commercial auto liability

- Commercial general liability

- Excess liability

- Business interruption

- Directors’ and officers’ liability

- Cyber liability from data breaches and ransomware

- Fidelity

- Workers’ compensation

- Employment practices liability

The lack of historical TNC loss data led TNCs to manage their insurance risk with a combination of self-insurance in the form of single-parent captive insurers and risk retention groups, as well as risk-transfer to reinsurers with quota share or excess of loss treaties. The largest TNCs and sharing companies have all formed captives. These include Uber’s Aleka, DoorDash’s Agora Insurance Company, Lyft’s Pacific Valley Insurance Company, and Airbnb’s Launa Insurance Company.

In the absence of historical loss data to inform ratemaking for this new economic sector, existing loss history for conventional PPA and commercial automobile insurance guided insurers’ ratemaking. TNC insurance results for insurers writing TNC coverage were poor. Insurers that took on TNC risk underpriced and under-reserved TNC business so much that balance sheet strength was challenged. The risk component TNC companies retained also proved inadequately reserved, leading to several rounds of large losses, adverse prior accident year loss development, and significantly higher accruals to their captives.

This study analyzes insurance challenges for the TNC sector. It identifies the issues that have made TNC insurance challenging and proposes responses to introduce more stability into TNC insurance—for rideshare drivers, customers, insurers, TNCs, and their shareholders.

Part 1: TNCs Face Challenges on Many Fronts

Social Inflation, Tort Trends

Social inflation, a form of legal system abuse, has exerted and continues to exert upward pressure on courtroom civil liability litigation tort trends. The issue has also impacted TNC defendants. It occurs when growth in civil litigation awards outpaces economic inflation, measured by the change in the consumer price index (CPI). The impact of social inflation on insurer results is felt mainly in commercial liability and commercial auto lines but also impacts the liability portion of PPA insurance.

There have been many useful studies that include data to support the case that social inflation balloons third-party liability awards at a rate higher than increases in the CPI. In fact, the only recent study to challenge the notion that social inflation is a real phenomenon is a journal article by a consumer advocate.

R Street has continued to engage with the issue of social inflation, including in a 2021 study, a more recent analysis of third-party litigation funding (TPLF), and a submitted testimony at a congressional hearing on TPLF. However, the issue persists, and insurers’ continuing concern is evident in remarks by Chubb CEO Evan Greenberg:

[Social inflation] is the problem that is enduring. It’s not episodic. It’s not going away, and it is getting worse […] more individual verdicts, class action lawsuits and new theories of liability are all driving up the cost of settlements and verdicts […] the trial bar has developed into a money-making industry with new funding sources, and society is becoming more anti-corporation.

The anti-corporation sentiment to which Greenberg refers is exacerbated by politics, and stoked by strong populist sentiment in Republican, as well as Democratic, administrations. Such populism appears poised to continue at least through 2028, regardless of the occupant of the White House.

Attorney Involvement in Claims

Increased attorney involvement in auto claims drives up average claim severity and the length of time that elapses until a claim is closed. One survey found that 57 percent of surveyed personal and commercial auto insurance claimants engaged lawyer services before filing their claim. Further, the survey found that 85 percent of respondents were solicited by an attorney after the accident, and 60 percent heard from two or more attorneys.

A claims adjusting firm found that attorney involvement in commercial auto claims rose in the past five years. Another study noted that increased attorney involvement in commercial claims is a direct cause of elevated loss ratios and that costs continue to rise. This study also found that 55 percent of litigated commercial auto claims have attorney involvement before or on the same day a claim is reported to the insurer, up from 43 percent only four years ago. Further, 67 percent of litigated claims have attorneys involved within the first 14 days of claims being reported.

In another study by a data provider, they found that over 50 percent of attorney-represented claims are reported to attorneys prior to the injury report, and 80 percent of those claimants made that decision within 24 hours of the accident. It found further that 93 percent of claimants who sought legal counsel were likely to retain legal services in the future.

Loss Severity

Higher claim severity for litigated claims is due in part to attorneys learning the limits of the insurance policy and crafting their demand at or close to policy limits. At a conference of the Auto Insurance Report, a former Auto Club VP said that attorneys are, “building the case to the policy limit.” There is even a cottage industry of firms that research and identify policy limits and sell that information to plaintiff attorneys. One such firm advertises that it charges as little as $175 to find personal auto liability insurance limits and upwards of $305 to find commercial auto insurance limits.

A study by an actuarial consulting firm on attorney involvement found that attorney involvement led to higher awards. It found, for claims closed in 2019, that the average loss for claims represented by an attorney was 14.3 times higher than the average loss for claims without an attorney. Similarly, the average cost for resolving a claim with an attorney was 34 times higher than without. The average total defense and cost containment expense (DCC) (formerly called allocated loss adjustment expense, or ALAE) for claims with an attorney was 15.3 times higher than the average cost for claims without an attorney.

Similarly, a study by data provider LexisNexis found that claim severity rose by 20 percent since the pandemic, and physical damage claim amounts rose by 47 percent.

Uber has reported that in its California business with one insurer, when $100,000 is the limit available for a UM/UIM insurance claim, 96 percent of personal auto claims settle below $100,000. However, if the limit for a UM/UIM claim is $1 million, only 56 percent of claims settle below $100,000. In addition, UM/UIM claims are 45 percent more likely to be attorney-represented over personal auto claims. Furthermore, UM/UIM severity is 10-12 times that of personal auto UM/UIM severity.

Data from another insurer compared UM/UIM premiums in period 2 (when a driver is transporting a customer) in states with $1 million TNC UM/UIM limits, such as Vermont and Oregon, to industry-wide PPA data. The comparison found TNC premiums to be many multiples higher than the generic industry premium.

An insurance research firm that also reported on increased attorney involvement in claims attributed the increase in part to increases in attorney advertising, including commercial ads by lawyers who advertise on billboards (billboard lawyers).

Louisiana is an example of a state where high loss severity is driven by elevated medical costs. In fact high limits as well as other factors have made it among the most challenging states for insurance.

Payment Patterns

If insurance company pricing and reserving actuaries have not recognized the extended timeframe of payments, older accident years may prove to be deficient or insufficiently reserved. This would constitute a change to the payment pattern, prolonging the duration of claims payments and stretching them out over more years. This results in claims costing more before they are closed. Auto liability loss reserves have traditionally been among the most straightforward to analyze for rate adequacy, whether deficient or redundant. PPA payment patterns have traditionally been very stable, with short tails (meaning that claims are paid quickly) and a large corpus of claims data to inform ratemaking. However, in the past decade, payment patterns have lengthened. This has made reserving for losses less reliable and has called pricing adequacy into question.

Use of attorneys in routine automobile accidents increases settlement times and contributes to lower paid-to-incurred ratios and larger ultimate losses. If attorney representation is not fully captured by reserving actuaries, there will be resulting adverse prior accident year loss development, fueling the need for higher rates.

In Table 1, a comparison of the first year paid-to-incurred ratios for State Farm, Progressive, and Allstate shows lower paid-to-incurred ratios than a decade ago, and more incurred but not reported (IBNR) posted, indicating losses will take longer to develop to ultimate. In the table below we see, for example, that Progressive’s paid-to-incurred ratio fell from 49.5 percent in 2014 to 40.8 percent in 2023.

Table 1: Paid-to-Incurred Ratios

| 2014 | 2023 | Change 2014-2023 | |

| State Farm | 41.4% | 35.1% | -15.2% |

| Progressive | 49.5% | 40.8% | -17.6% |

| All State | 38.6% | 32.0% | -17.1% |

The consistency between the three top auto insurers in changes to their paid-to-incurred ratio is remarkable. The story these numbers tell is that in 2014, close to half of claim amounts were paid in the most recent accident year, whereas in 2023, approximately one-third of claims are paid out in the first year.

Table 2 likewise demonstrates, in a comparison of the volume of bulk reserves (IBNR) put away in the most recent accident year, that auto insurers are taking longer to settle claims. The data shows that the top-three auto insurers are putting considerably more than they used to into long-term reserves. This is in response to experiencing claims of longer duration. Allstate, for example, put almost twice as much into bulk reserves in 2023 compared to 2014. Claims that used to be paid and closed in less than a year are now open for two years or more.

Table 2: IBNR-to-Incurred Ratios, PPA Insurance

| 2014 | 2023 | Change 2014-2023 | |

| State Farm | 31.1% | 36.8% | 18.3% |

| Progressive | 13.5% | 19.1% | 41.5% |

| All State | 12.1% | 22.8% | 83.9% |

marketintelligence/en/solutions/sp-capital-iq-pro#five-new-reasons.

Attorney Advertising

Saturation attorney advertising includes ubiquitous multimedia messaging from plaintiff attorney firms on billboards, the internet, radio, the sides of buses, and television. It is extremely effective in driving higher awards, including “nuclear” verdicts (i.e., those above $10 million). A 2024 R Street webinar reported that the average frequency of legal services television advertisements in 2023 was 45,000 ads per day, which translates into 1,876 per hour, or one ad every two seconds across the United States.

The litigation type targeted by the most legal service ads in 2023 was personal injury resulting from accidents, with legal ad spending at $1.0 billion. The distant second and third litigation types targeted in legal ads were environmental contamination, at $59 million, and asbestos, at $51 million in spending. The top local markets for attorney advertising were New York City, New Orleans, Houston, Detroit, and Philadelphia. One Chief Claims Officer points out that a factor driving more and earlier attorney involvement is a “significant increase in attorney advertising.”

Phantom Damages

The practice of third-party medical funding (TPMF), also known as consumer funding, enables funders and personal injury lawyers to profit when the amount of medical services billed exceeds the amount actually paid to medical providers. In TMPF, accident victims transfer their rights of recovery from medical bills to a third-party funder with a lien. The Government Accountability Office (GAO) defines consumer funding as “arrangements between a funder and an individual person, such as the plaintiff in a personal injury case.”

TPMF differs from Medicare or Medicaid in that funders refuse to negotiate lien reductions. This drives up the cost of defense and hinders settlements. There are 25 states that allow full recovery of phantom damages. Eleven states permit jurors to consider the existence of phantom damages.

Regulatory Inertia

The amount of time insurance regulators take to approve or respond to rate filings ranges widely from state to state. A study by an actuarial consulting firm analyzed the average number of days individual states take to approve a rate filing for PPA insurance. Those with the most average days were Hawaii (112 days), Texas (118 days), Vermont (92 days), and New Jersey (74 days). Those with the fastest rate filing turnaround times were North Carolina (17 days), Nebraska (19 days), Arkansas (21 days), and Illinois (23 days).

It is noteworthy that the actuarial firm analysis did not include data on California. California is unique among states in having exceptionally long lags between filings and responses to rate filings as a result of straitjacketing insurance legislation introduced in 1988: Proposition 103. A separate actuarial consulting firm analyzed California rate filing delays. It found that responses to rate change filings for new programs rose from 80-90 days in 2012 to approximately 350 days in 2023, and other filings (rule and form filings) increased from approximately 65 days to approximately 150 days. Other indicators of the efficiency or inefficiency of state insurance regulation are analyzed in R Street’s 2022 Insurance Regulation Report Card.

Insurance Fraud

Insurance fraud is one of the largest categories of white-collar crime, second only to tax evasion. Insurance fraud measures $308.6 billion annually. If insurance fraud were eliminated entirely, premiums for policyholders would be approximately 10 percent lower. One of the largest categories of insurance fraud is staged automobile accidents, which are responsible for driving up the cost of PPA and commercial auto insurance. Criminal rings are increasingly staging accidents involving trucks because there is potential for larger monetary awards in truck accident scams than staged accidents involving personal autos.

Some recent staged accidents were perpetrated by large fraud rings. Among the largest organized staged accident schemes was one in Louisiana, with over 150 accidents, dozens of arrests, a guilty plea by a complicit attorney, and the gangland-style execution of one participant who had turned witness. It led to indictments for 52 people, 44 of whom pleaded guilty.

Dishonesty Among Younger Customers

A disturbing trend likely to keep staged accidents at elevated levels is the willingness of younger generations to tolerate insurance fraud. A recent survey found that respondents aged 45 and younger are more accepting of insurance fraud, even to the point that a significant number of individuals feel envious of those who commit insurance fraud, inspiring them to want to do so as well.

The survey found that insurance fraudsters may justify cheating an insurance company because they consider it to be a victimless crime. In fact, close to 9 percent of respondents justified insurance fraud as not being wrong or criminal because they believed that “insurance companies rip people off, so it’s fair” and “I pay them enough, it’s my money I’m getting back.” The survey revealed a significant percentage of respondents (28.6 percent) believe insurance fraud is “not a real crime” (8.5 percent) or a “business practice with no real victim” (20.1 percent).

The finding that younger people are more tolerant of insurance fraud and are less likely to see it as a crime than older people has negative ramifications for the insurance industry. As today’s younger generations reach middle-age and the more mature generations age out of the economy, there will be a higher proportion of Americans who believe that insurance fraud is justifiable and who are more willing to perpetrate it.

The combination of the above factors is responsible for stoking claim amounts and hiking required reserves ever higher. For example, large IBNR reserve increases by one TNC firm in the past two years reflects the rise in its insurance costs. As Table 3 shows, with this firm’s overall 2023 expenses at $36.1 billion, large swings in insurance expenses on the order of $1 billion or $2 billion can have a material impact on the company’s bottom line.

Table 3: Short-Term and Long-Term Insurance Reserves

| 2022 | 2023 | Change | |

| Long-term insurance reserves | 1,692 | 2,016 | 19.1% |

| Long-term insurance reserves | 3,022 | 4,722 | 56.3% |

https://d18rn0p25nwr6d.cloudfront.net/CIK-0001543151/6fabd79a-baa9-4b08-84fe-deab4ef8415f.pdf.

Part 2: Insurance and Public Policy Solutions to TNC Issues

Just as there are numerous drivers of higher TNC insurance costs, there are numerous actions that TNCs could consider to guide insurance costs toward more predictable, reasonable levels.

Lower Limits

As in past insurance cycles, the soft market phase is characterized by rate reductions, more generous terms and conditions, and higher limits. In the soft market years prior to 2019, casualty limits rose, and liability insurers put up higher primary limits to be competitive with the market. In today’s environment, with close to five years of a hard market, insurers are retaining more risk, pushing up reinsurance attachment points. The same should be done for UM/UIM, as the current limits of $1 million for TNCs and commercial auto makes TNCs an easy target for plaintiff attorneys seeking to profit from deep-pocketed defendants.

California, which pioneered UM/UIM, stipulated soon after the introduction of UM/UIM to the market that UM/UIM limits should accord with liability limits, which are substantially less than $1 million. The purpose of UM/UIM is to provide protection to a prudent driver in the event of an accident involving an at-fault insured motorist whose insurance coverage limits are in line or above minimum financial responsibility limits. The wide disparity in many states between minimum liability limits and UM/UIM limits supports narrowing the gulf between the two.

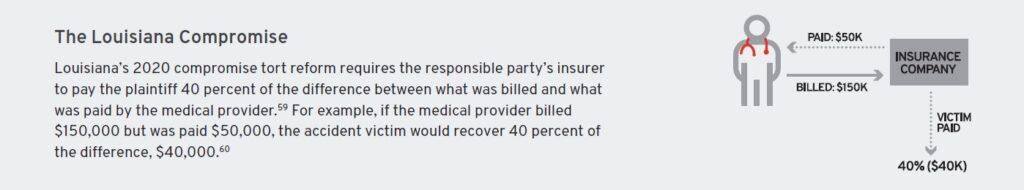

Overturn Collateral Source Rule

The collateral source rule stipulates that if an injured person receives compensation for his injuries from a source wholly independent of the tortfeasor, the payment should not be deducted from the damages that he would otherwise collect from the tortfeasor. However, the enactment of this rule across the 50 states is patchy at best. Disallowing the collateral source rule has long been an objective of tort reform advocates and should continue to be. The recent partial rollback of Louisiana’s collateral source rule shows that progress is possible.

Call Out Phantom Damage Abuse

The phenomenon of phantom damages has long been recognized as a driver of social inflation. Whether phantom damages are allowable is a tort reform issue that numerous states continue to debate. The contention emanates, in part, from the numerous red flags indicating that phantom damages may be exploited. These include:

- Uncharacteristically high cost for back surgeries. The cost of lumbar spinal fusion ranges from approximately $50,000 to $80,000. Phantom damages of 100 percent can generate a large five-figure windfall for funders and attorneys. One law firm reported billings as high as several hundred thousand dollars for soft tissue treatments in low-speed car accidents.

- Reporting unrelated injuries. Accident victims report symptoms after a crash totally unrelated to cover expensive procedures performed many months after the accident.

- Unqualified medical providers. Physicians referred by third-party funders may have no experience in the treatment required, which can lead them to misdiagnose issues.

- Inconsistency in medical payment practices from state to state. There is inconsistency in medical payment practices from state to state. Treatment for the same accident by varying providers typically results in different payment amounts. There may also be a difference between the amount incurred, or billed, for a treatment, and the amount actually paid. The differences from provider to provider and between amounts paid versus incurred create inconsistency and lead to a reduction in the predictive reliability of case loss reserving.

Adopt the Maryland Model

Unlike most states, where the cost of a given medical procedure varies from one hospital to another and from one payer to another, the Maryland Total Cost of Care (MD TCOC) model requires all payers, whether private, commercial, Medicare, Medicaid, or self-paid, to be charged the same rate for the same service at the same hospital. The Maryland model is good for patients because it eliminates billing surprises, and it is good for hospitals, providers, and TNC insurers because it makes for greater stability and predictability. The Maryland model seeks to improve the overall health of Marylanders, reduce avoidable hospital readmissions and emergency room visits, and improve the patient experience.

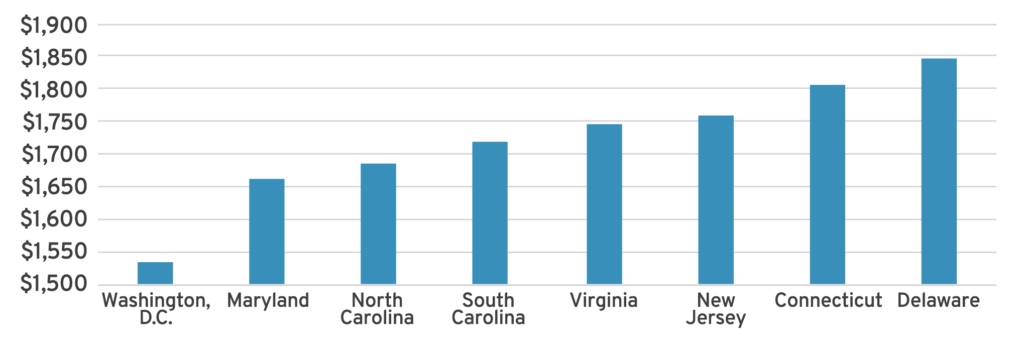

Maryland’s TCOC is thought to be responsible for average health insurance premiums for employees in the state with single coverage through employer-provided health insurance being lower than in surrounding states. As Figure 1 shows, with the exception of Washington, D.C., Marylanders pay lower health insurance premiums than residents in surrounding states.

Figure 1: Average Health Insurance Cost

Source: Cassidy Horton and Kelly Anne Smith, “The Most (and Least) Expensive States for Healthcare 2024,” Forbes Advisor, March 18, 2024. https://www.forbes.com/advisor/health-insurance/most-and-least-expensive-states-for-health-care-ranked.

Maryland also has the lowest costs for unintentional injury deaths. The average cost in Maryland, $3,054, is approximately two-thirds lower than in the most expensive, West Virginia, at $8,607.

Introduce Occupational Accident Alternative

Occupational accident (Occ/Acc) insurance was created to address the insurance needs of independent contractors ineligible for workers’ compensation insurance. It is an optional coverage that costs approximately 30 percent less than workers’ compensation insurance. It was first introduced to provide a solution for truck owner-operators and has expanded to cover others in the gig/freelancing economy. Occ/Acc insurance provides some coverage for lost wages and medical expenses, as well as death benefits for survivors. Unlike workers’ compensation, in which benefits are unlimited, Occ/Acc claims are subject to policy limits. Occ/Acc is written on a group basis.

Slow Down Runners and Ambulance Chasers

Restrictions on ambulance chasing could help stem the tide of aggressive solicitations by attorneys who mine accident reports to identify prospective injured plaintiffs.

Black’s Law Dictionary defines a runner as a “person who solicits business for [an] attorney from accident victims” and defines an ambulance chaser as one who “on hearing of a personal injury which may have been caused by the negligence or wrongful act of another […] at once seek[s] out the injured person with a view to securing authority to bring action on account of the injury.”

The American Bar Association has rules circumscribing attorney solicitation, and some states have passed their own legislation restricting the unseemly practice of ambulance chasing. For example, in 2014, Georgia passed House Bill 828, spelling out penalties for the practice of ambulance chasing. The bill protects injured people because it allows them time to research and choose an attorney, rather than be pressured by aggressive solicitations. The bill prohibits “the solicitation, release, or sale of automobile accident information.” It also defines running and how attorneys and runners can be penalized for this unethical and illegal practice.

There are 20 other states, in addition to Georgia, in which ambulance chasing is illegal. In states where it is legal, such as Missouri, it is straightforward for attorneys to prospect for clients because, following an accident, the Missouri State Highway Patrol makes public accident reports available immediately. The reports include the names of those involved in the accident, injury severity, insurer, and the hospital.

UM/UIM History – Addendum 1

With the exception of New Hampshire, the “live free or die” state, all others require drivers to have some form of insurance coverage. UM/UIM coverage was designed to cover accident victims and recover their costs if the at-fault driver has minimum limits or no insurance coverage. UM/UIM differs from no-fault or personal injury protection (PIP) in that no-fault provides coverage regardless of who was responsible for the accident. Therefore, to obtain coverage under UM/UIM, the injured driver must prove the other driver was at fault.

UM coverage was developed by insurers in the 1950s in order to prevent compulsory automobile insurance. It went into effect in California in 1961 with minimum limits of 15/30. Inflation has eroded the value of these limits, and they have risen in most states; the most common UM/UIM limit is 25/50.

Lessons from The Michigan Experiment

One reason that motorists carry no coverage at all is because of the expense of required automobile liability insurance coverages for third-party bodily injury and third-party property damage, combined with the high cost of coverage for comprehensive and collision. There is wide variation across states in terms of the percentage of drivers who are uninsured or underinsured. It ranges from a low of 5.9 percent in Wyoming to a high of 25.2 percent in the District of Columbia. The national average in 2022 was 14.0 percent. Tables 4 and 5 present the national percentage of uninsured drivers and states with the highest and lowest percentage of uninsured drivers.

An actuarial consulting firm explored the reasons for the percentage of drivers with no insurance across the country. It found that drivers in states with the highest percentage of uninsured drivers did not buy insurance because of socioeconomic factors, including income, employment, and education. The study found that the lowest-earning families who lacked steady employment and had low educational attainment also had the highest rates of UM/UIM. Conversely, states where income, education, and employment were high

had the lowest rates of UM/UIM.

Table 4: Percentage of Uninsured Drivers, National Average

| Year | Percentage |

| 2017 | 11.6% |

| 2018 | 11.5% |

| 2019 | 11.1% |

| 2020 | 13.9% |

| 2021 | 14.2% |

| 2022 | 14.0% |

Table 5: 10 States with Highest and Lowest Percentage of Uninsured Drivers

| Highest | Lowest |

| D.C. 25.2% | WY 5.9% |

| NM 24.9% | ME 6.2% |

| MS 22.2% | ID 6.2% |

| TN 20.9% | UT 7.3% |

| MI 19.6% | NH 7.8% |

| KY 18.1% | NE 7.8% |

| GA 18.1% | ND 7.9% |

| DE 18.1% | KS 8.0% |

| CO 17.5% | SD 8.0% |

| OH 17.1% | MI 8.7% |

The introduction of no-fault insurance in Michigan in 1973 was an experiment to develop an approach more advantageous than a tort liability system. Its aim was to be fair and give policyholders more benefits at lower costs.

The impetus for the drafters of no-fault insurance was to create a system similar to workers’ compensation, where injured workers give up their right to sue their employer following a workplace injury in exchange for guaranteed reimbursement of medical expenses and lost time (the “grand bargain”). The disadvantages of a tort system for auto insurance were:

- The fault standard caused many victims to be completely uncompensated or undercompensated.

- There was a considerable delay in obtaining compensation because of the workings of the civil litigation system.

- There was inconsistency in how injured drivers were compensated—some were compensated too much, others too little.

- It was hard to ascertain who was at fault, and it was complex and expensive.

- There was substantial dishonesty in presenting the facts of an accident.

Supporters of no-fault argued it would reduce litigation and ultimately lead to lower auto insurance premiums for policyholders. It was designed as a tradeoff; policyholders would have more certainty regarding how much they would receive in claim payments, and at the same time insurers would benefit from lower loss adjustment expenses (LAE) in the absence of litigation. In the first half of the 1970s, 16 states adopted some form of mandatory no-fault. However, in the 1990s, it became apparent that no-fault was not achieving its goal, and support from large insurers waned.

Instead of auto insurance premiums declining from no-fault, premiums rose. This was because of:

- Unlimited medical coverage

- Uncontrolled utilization

- Lack of a medical fee schedule

These problems led to medical providers prescribing more services than required and contributed to fraud and abuse.

One study found that injury costs under no-fault rose from 12 percent higher above tort in 1987 to 73 percent higher by 2004. This result was the opposite of what was sought: No-fault was supposed to be cheaper than tort. The study also found that states that restricted lawsuits against other drivers in order to reduce costs had higher claim costs than states allowing litigation.

Soon after the introduction of no-fault, insurers realized that they had inadvertently surrendered their ability to control medical costs for accident victims because the no-fault system offered unlimited medical costs. This drawback led to automobile insurance premiums in Michigan being the highest in the nation. For instance, in 2019, the average cost of automobile insurance in Michigan was $2,611, whereas the average premium in the United States was $1,457. The second highest behind Michigan was Louisiana, at $2,298. However, in 2022, three years after Michigan’s no-fault system was reformed, the state with the highest auto insurance premium was Florida, at $2,560. Michigan had fallen to the fourth highest, at $2,133. This suggests that the reforms worked.

One of the drivers of Michigan’s high automobile insurance premiums is elevated loss exposure in Detroit. Detroit has been plagued with high incident rates of theft, and attorneys frequently being involved in auto insurance claims. PIP loss severity for Detroit was approximately twice as high as that of surrounding counties.

One consequence of the high auto insurance cost in Michigan was an increase in drivers not buying automobile insurance. To be sure, in 2019, 25.5 percent of Michigan drivers were uninsured. This was the highest of any state, with the exception of Mississippi. It is also more than twice the national average of 12.6 percent. Three years after passage of the 2019 Michigan reforms, in 2022, the percentage of uninsured drivers in Michigan fell to 19.6 percent, and Michigan became the fifth-highest state for uninsured drivers.

The 2019 Michigan no-fault reform package introduced four changes:

- PIP coverage options. Policyholders were offered five options for the level of PIP insurance. They could get lower premiums if they made their health insurance coverage the primary source of coverage for auto accident-related medical costs.

- Medical cost controls. Insurers would reimburse medical care providers at no more than 230 percent of Medicare costs. For costs that are not covered by Medicare, care providers are only responsible for 55-78 percent of their fee schedules for the services they provide.

- Controls on utilization. Insurers are allowed to conduct utilization reviews to determine if the amount and quality of medical treatments are in line with accepted standards for medical providers.

- Minimum liability insurance. The minimum liability insurance requirements are raised to $50,000 per person and $100,000 for all persons.

The Michigan experience with no-fault exemplifies the power of unintended consequences, and that reforms can work.

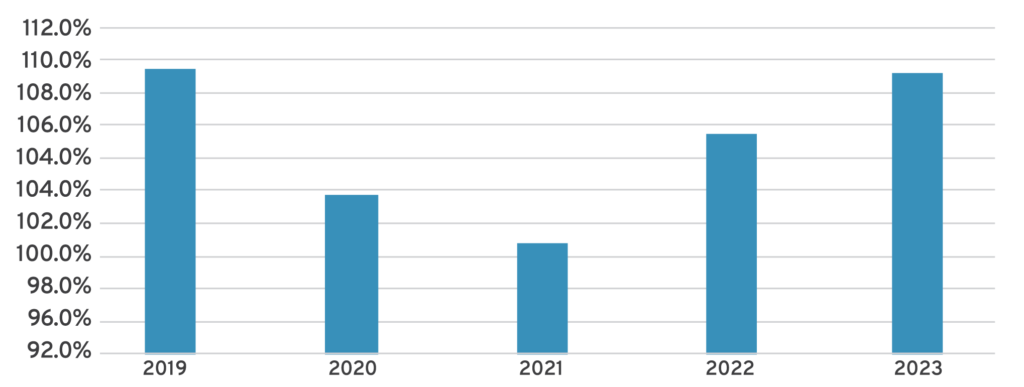

Tough to Make a Buck in Commercial Auto – Addendum 2

Commercial automobile liability insurance has been the worst-performing insurance line for close to a decade. Prior to the pandemic, its combined ratio remained close to 110 percent. The combined ratio fell during the pandemic years, as roads were emptier, even dipping below 100 percent in one year, but it has recently returned to highly unprofitable territory, with a combined ratio of 109.2 percent in 2023. Because TNC coverage is commercial, TNC insurance performance is affected by some of the same factors responsible for commercial auto’s elevated combined ratio. It is therefore instructive for TNCs to be familiar with commercial auto trends.

Figure 2 below shows that, with the exception of 2021, commercial auto insurance saw underwriting losses in the past five years, with 2019 and 2023 delivering the most unprofitable results.

Figure 2: Commercial Auto Combined Ratio

Source: S&P Capital IQ Pro, last accessed Sept. 10, 2024. https://www.spglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/solutions/sp-capital-iq-pro#five-new-reasons.

In addition to the unprofitable results for commercial auto insurance, the failure of a commercial auto insurer owned by a long-haul trucking firm conveys the severity of the line’s troubles. In 2021, the nation’s fifth-largest long-haul trucking company, Knight-Swift, launched a plan to provide trucking-related services, including insurance, to third parties. In its announcement, the CEO commented that the service “brings wholesale prices within reach for all trucking businesses, regardless of size.”

The venture into the insurance business was ultimately a failure, with insurance and claims rising from $456 million in 2022 to $610 million in 2023. The unit that provided the insurance services to third-party trucking firms reported a $125.5 million operating loss for its business in 2023. The poor results, which included continued unfavorable development of insurance reserves, led the company to announce exiting all third-party insurance business in Q4 2023.

Another large publicly-traded long-haul trucking firm, Werner, felt the pain of truck insurance losses and reported that its liability insurance premiums in 2023 were $1.0 million higher than in 2022. The premium increase was driven by “small dollar liability claims, increasing cost-per-claim, and increased cost for repairs.” The company also reported that its unfavorable prior accident year reserves in 2022 were caused by:

unexpected and unfortunate legal developments for two prior year motor vehicle accidents that have been settled, including a settlement of a lawsuit in Texas arising from a May 24, 2020 accident for which we recognized $9.5 million of insurance and claims expense in 2022.

They also reported having incurred insurance and claims expenses of $5.7 million and $5.4 million in 2023 and 2022, respectively, for accrued interest related to a 2018 adverse jury verdict.

Conclusion

Pricing TNC insurance business with rates commensurate with risk has proven to be a thorny challenge. Due to its status as a commercial insurance product, factors driving TNC insurance losses are not unlike social inflation-related drivers of commercial auto losses. In addition to social inflation driving ever larger awards, several factors peculiar to TNCs contribute to adverse loss trends, including rising average loss severity, increased involvement by attorneys, extended payment patterns, attorney advertising, phantom damages, excessively high UM/UIM limits, regulatory inertia, and insurance fraud. The rising loss trend has numerous deleterious consequences for publicly traded insurers and TNCs, which experience volatile results that even impact share prices, leading to rating agency downgrades and increased costs for drivers and investors.

TNCs and insurers should respond to adverse TNC loss trends in a number of ways.

- Insurers and TNCs should present the case to regulators that UM/UIM limits should be lowered to be consistent with other automobile insurance coverages.

- Tort reform efforts should target the collateral source rule in states where it allows plaintiffs to be compensated twice.

- Phantom damages should be proscribed, as they allow plaintiffs and their attorneys to monetize the difference between paid and incurred losses.

- The example of Maryland, where providers are charged the same rate for the same service at the same hospital, should be adopted by other states.

- Occ/Acc insurance should be introduced to limit cost shifting where providers get larger reimbursements from auto insurance than obtainable from Medicare/Medicaid.

- Action should be taken against the unseemly practice of ambulance chasers and runners, where aggressive attorneys take advantage of injured drivers.

Some combination of success with these six recommendations should contribute to TNCs and their drivers having more reasonable and reliable insurance rates in the future.