Restorative Justice

Author

Media Contact

For general and media inquiries and to book our experts, please contact: pr@rstreet.org

Disclaimer: This research was funded in part by The Annie E. Casey Foundation and the R Street Institute. We thank them for their support; however, the findings and conclusions presented in this report are those of the author alone and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of these organizations.

Restorative justice is an alternative approach to crime focused on repairing harm and restoring relationships.

Introduction

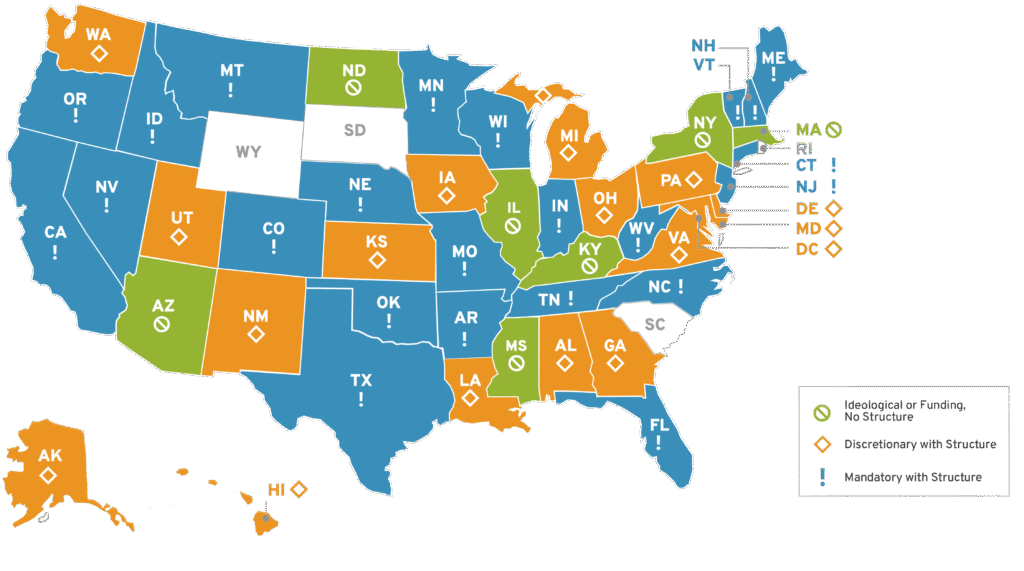

While restorative justice has rapidly gained traction in the 21st century (see Figure 1), it is one of the oldest concepts in criminal justice. From international peacemaking tribunals to school playgrounds, its framework can be adapted to fit almost any situation. Restorative justice works by bringing together a person who caused harm, the victims of that harm, and relevant community members to discuss what happened and how to make it right (a “restorative conference”). This approach promotes accountability without the life-altering pitfalls associated with court, probation, or detention. Furthermore, it places victims front and center, recognizing that the people most affected by a crime are best equipped to determine a just outcome.

Figure 1: Restorative Justice Laws in the United States

What’s wrong with the current system?

The adult and juvenile systems are different in many ways, but they share the same model: On one side, a defense attorney stands in for the defendant; on the other, a prosecutor stands in for the victim. This adversarial structure creates a winner-takes-all dynamic that incentivizes both sides to conceal what really happened. Instead of searching for truth and reconciliation, both the prosecution and defense are trained to beat the opposing side—regardless of what actually occurred.

What’s different about restorative justice?

Restorative justice represents a philosophical shift in how we think about crime and punishment. By directly involving victims, family, and the community, it offers a 360-degree response to juvenile delinquency. Under a restorative framework, crimes are not acts against an impersonal, monolithic state; rather, they are acts against specific people. Instead of owing a debt to society, people who have caused harm owe a debt to their victims. In this way, restorative justice re-contextualizes crime as primarily a breach of human relationships. Instead of fixating on which statute was broken and who should be punished, restorative justice focuses on who was harmed, who was responsible, and how that harm can be repaired.

| Restorative Justice | Retributive Justice |

|---|---|

| Crime violates people and relationships | Crime violates the state and its laws |

| Justice focuses on needs and obligations so things can be made right | Justice focuses on establishing guilt so punishment can be applied |

| The central parties are the victim and the person who caused harm | The central parties are the state and the defendant |

| Justice is sought through dialogue and mutual agreement | Justice is sought through a conflict between adversaries |

| Accountability is achieved by making amends and repairing harm | Accountability is achieved by punishing offenders |

How does it work?

Restorative justice works best as part of a coordinated diversion strategy. In a typical conference session, a trained facilitator brings together the offender, the victim, and family or community supporters for each party to discuss what happened, what harm was caused, and what steps are required to repair that harm. This may involve an apology, restitution (e.g., paying for damaged property), and/or a plan to address underlying issues, including regular attendance at school or counseling. The victim has a chance to express their experience and needs, and the person who caused the harm is held accountable for their actions. Once the plan has been fulfilled to the satisfaction of the victim (or victim surrogate), the case is dismissed without a formal adjudication.

Why is restorative justice well suited for juveniles?

Youth are still developing both cognitively and emotionally, making them an ideal population for restorative intervention. The prefrontal cortex—responsible for decisions and impulse control—develops rapidly during adolescence. This higher neuroplasticity is a double-edged sword: While it makes teens more susceptible to negative influences, it also makes them more responsive to rehabilitation. Addressing delinquent behavior through constructive measures before it escalates to serious crime can prevent the negative downstream effects of formal prosecution and incarceration.

What about victims of crime?

Currently, only 1 in 3 crime survivors get help recovering from the emotional, physical, and financial harm, while more than half report being ultimately unsatisfied with the outcome of their case. Empowering individuals to narrate their trauma and define their own needs can be a critical step in transcending the experience of a crime. People are more likely to be satisfied with an outcome when they feel the process was fair and their voice was heard. A 2023 meta-analysis found that victims experience considerable reductions in negative emotions (e.g., fear, anger, guilt, anxiety, distress) after a restorative conference. By actively involving those affected by a crime in finding a resolution, restorative programs increase the process’ perceived legitimacy among offenders and victims alike.

Does restorative justice let youth off the hook?

Accountability in the traditional justice system is passive—the court hands down a sentence, and the offender receives their punishment. There is no requirement to take responsibility for what happened or even acknowledge harm occurred at all. Rather than imposing penalties from the outside, restorative justice insists that individuals actively take accountability. This includes intentionally confronting the harm they caused, working to make amends, changing antisocial behaviors, and earning back trust through positive action. This process builds character, an internal sense of responsibility, and reconnection to community norms. In fact, taking personal responsibility for one’s actions is a cornerstone of criminal rehabilitation.

What does the data say?

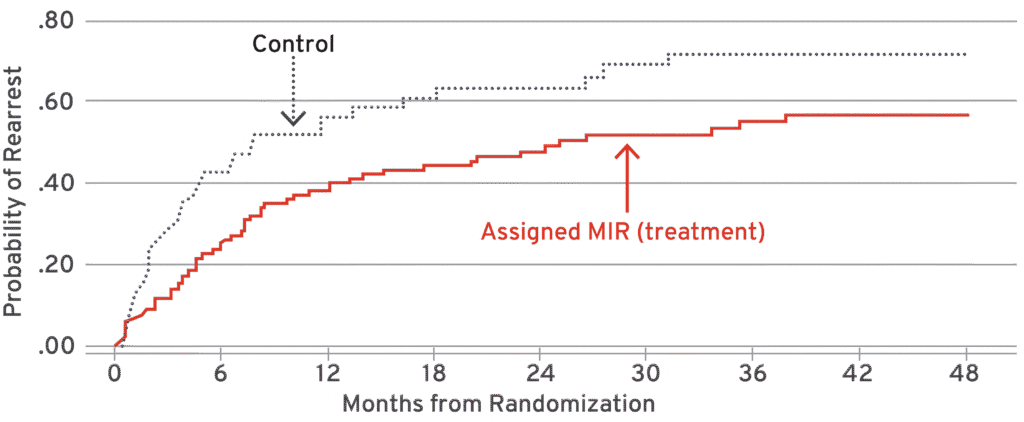

In 2022, researchers used a randomized controlled trial—the gold standard in social science—to evaluate a restorative justice program in San Francisco called “Make-it-Right,” randomly assigning either a restorative conference or juvenile court to eligible youth charged with mid-level felonies (e.g., burglary). Results showed that Make-it-Right participants were 20 percent less likely to be rearrested in the follow-up period compared to the control group (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Rearrest Probability Curve in the Four Years Following Make-it-Right

Is restorative justice right for every case?

Restorative processes rely on the offender to take ownership of their actions and participate in good faith. Restorative justice is generally not suitable for youth who refuse to accept responsibility or for serious crimes like sexual assault, where a face-to-face meeting is impossible or inappropriate. Proper screening is needed to identify the right cases and to ensure participants have the cognitive and emotional capacity to engage meaningfully.

Conclusion

By bringing together victims, youth, and communities in search of win-win solutions, restorative justice challenges the notion that justice must be zero-sum. When those closest to injustice help resolve it, an ethic of co-responsibility emerges—a recognition that crime arises in a social context and that blame does not lie entirely with the accused. By emphasizing relationships, restorative justice heals both the victim and the offender, offering a new route to protecting public safety and promoting the common good.