To Make International Plastics Treaty Succeed, Focus on Pollution Instead of Politics

Introduction

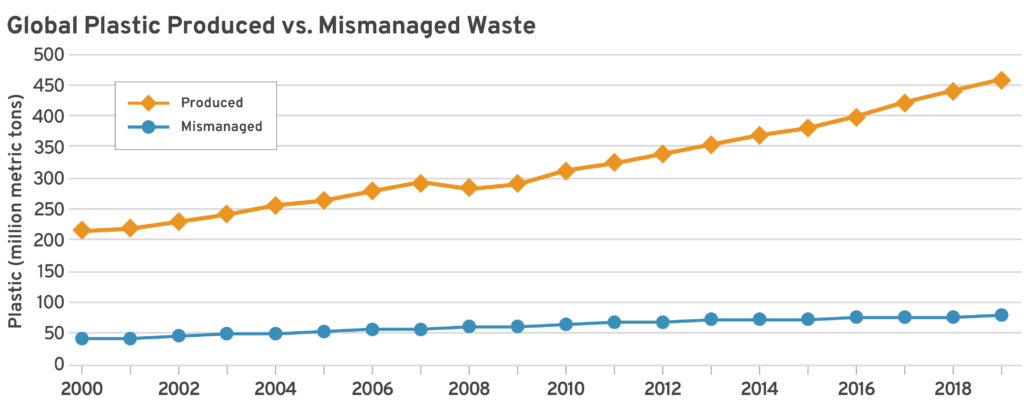

Soon, representatives of many of the world’s nations will once again convene to negotiate a global treaty aimed at reducing plastic pollution. This treaty is important: The world’s annual mismanaged plastic waste has increased by 95 percent since 2000, rising from 40.19 million metric tons in to 78.26 million metric tons in 2019. This increase shows no sign of abating, and given the uncertainty as to the effects of plastic waste on environmental quality and public health, it represents a clear collective action problem that an international treaty should aim to resolve.

Unfortunately, negotiation efforts have not been fruitful to date. A likely reason is negotiators’ insistence on shifting focus away from pollution mitigation to indirect policy solutions, such as capping plastic production.

Where Plastic Pollution Comes From

The rationale from negotiators who seek production caps as a means of combating plastic pollution is that if less plastic is produced, then there will be less plastic pollution. The problem with this line of thinking is that there is not a linear relationship between production and pollution.

As noted earlier, mismanaged global plastic waste increased by 95 percent from 2000 to 2019. But global plastic production increased by 116 percent over that same period. This decoupling of production and pollution is becoming more pronounced, as global mismanaged plastic waste increased by 7 percent between 2015 and 2019, while production increased by 21 percent. The following chart illustrates this trend. To explain it simply, the idea that reducing plastic production translates to a reduction in pollution is not empirically supported in the data.

Plastic pollution in the environment generally comes from mismanaged plastic waste. This is when plastic products, such as packaging materials, shopping bags, or fishing nets, end up in the environment instead of a landfill or recycling facility. When discarded improperly, especially in a body of water, the environmental conditions erode the plastic into smaller pieces that do not organically break down and can be dispersed to other areas by wind or ingested by animals.

But not all plastic ends its life as mismanaged waste. Overall, the global rate of mismanaged plastic waste is about 17 percent of annual production; however, this varies considerably by country. Consider the following table, which enumerates the percentage of plastic waste mismanaged by country.

| Plastic Waste Generated (million metric tons) | Mismanaged Plastic Waste (million metric tons) | % Rate of Mismanaged Plastic Waste | |

|---|---|---|---|

| United States | 72.84 | 2.45 | 3% |

| Europe | 69.34 | 3.8 | 5% |

| China | 65.44 | 17.46 | 27% |

| India | 18.52 | 8.46 | 46% |

| Asia (excl. China and India) | 54.36 | 18.15 | 33% |

| World | 353.29 | 78.26 | 22% |

Policies focused on capping production—like those proposed for the international plastics treaty—fail to target pollution. This is especially important because only a handful of countries represent the lion’s share of plastic pollution. For example, an estimated 81 percent of plastic pollution emitted into the ocean comes from Asia, with the largest contributor being the Philippines at an estimated 36 percent of global plastic waste emitted.

In other words, plastic pollution is not something that goes up just because people produce and consume more plastic. Plastic pollution is on the rise because areas with rising plastic consumption are not adequately managing plastic waste.

What This Means for Policy

The policy implications of the earlier points are significant. An international treaty focused on improving the waste management of plastics in a handful of countries will mitigate far more pollution than trying to limit production. This is a lower-cost solution than finding low-cost substitutes for plastics, and lessons from the history of environmental treaties reveal why this is essential.

There is little argument that the most successful international environmental treaty is the 1987 Montreal Protocol (MP), which limited the consumption of ozone-depleting substances (ODSs) that were deteriorating the ozone layer. While one might be tempted to draw similarities between the MP and recent plastics treaty efforts, the recipe for the MP’s success was that low-cost substitutes for ODSs were relatively simple to produce. This reduced the cost of transitioning away from ODSs relative to the environmental benefit. Not only was the resulting mandate able to pass cost-benefit tests, it was also palatable to the public—which ultimately must support or reject policy.

Conversely, securing a meaningful global climate treaty that limits greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions has been especially challenging. A notable failure is the 1997 Kyoto Protocol (KP), which mandated emission reductions for rich countries while giving others—notably, China—an exemption from any requirement. The KP failed to secure ratification by the United States, and similar efforts for international climate treaties have repeatedly run into the challenge that major emitters like China and the United States are unwilling to commit to the burden of major GHG emission reductions.

In making an international plastics treaty, nation representatives must focus on what made the MP a success and why the KP failed. More simply, the lesson from history is that international treaties are more successful when the costs of compliance are low and the benefits are high. Guided by this logic, a more worthwhile focus of the international plastics treaty would be to improve the waste management capacity in highly polluting nations and clamp down on pollution in international regions (like discarded fishing gear in oceans). This also has the merit of benefiting people who are directly harmed by plastic pollution, which is more prevalent in areas with underdeveloped waste management infrastructure.

Conclusion

R Street research on plastics has noted that the greatest opportunities for mitigating waste both internationally and domestically hinge upon making it easier to dispose of and recycle plastics at the end of their useful life. This simple lesson of economics—that reducing pollution is easier when it is cheaper—should be a guiding principle for policy proposals.

While one can appreciate proponents’ intent in capping plastics production, an empirical approach to the issue does not show a linear relationship between production and pollution. Consequently, this weakens any evidentiary argument that a treaty limiting plastic production would bring sought-after plastic pollution abatement.

Put simply, to have a treaty that successfully reduces global plastic pollution, negotiators should focus on waste management policies that we know reduce pollution rather than ideas that politicians speculate might reduce pollution.