The Abatement Costs of the IRA Energy Subsidies Are Rising

Summary

- Recent data indicates that clean-energy growth is below the level anticipated to occur given increased clean-energy subsidies under the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA).

- In light of lower clean-energy growth and rising subsidy costs, the IRA’s effectiveness in stimulating clean energy has likely lessened while the overall abatement cost has increased.

- In comparing IRA costs relative to its estimated emission effects, the overall abatement cost of the IRA is estimated at $600 per metric ton of carbon dioxide (CO2). For the largest portion of the IRA’s costs—its electricity subsidies—we estimate the abatement cost to be $208 per metric ton of CO2.

Introduction

Updated emission projections from the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) provide new understanding as to the effectiveness of the energy subsidies expanded as part of the IRA in abating emissions. New EIA data shows misalignment between the overall trajectory of U.S. emissions and the IRA’s projected emission abatement, signifying an increase in the cost of IRA subsidies relative to their emission benefit.

U.S. Emission Projection Updates

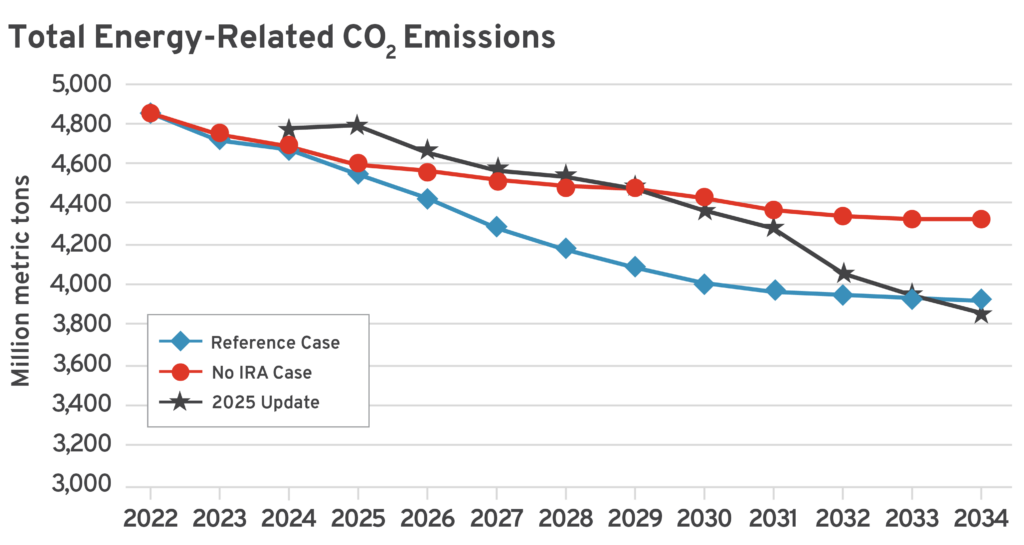

Overall, the EIA’s historical data for 2022 shows approximately 87 million metric tons of CO2 above what was projected, pushing U.S. emissions higher even before the IRA’s implementation. Additionally, the anticipated effect of the IRA subsidies on displacing fossil-fuel use has lessened in the near term. The following chart compares projected CO2 emissions from energy use to the reference case, including IRA subsidies, estimated in 2023; a no-IRA case also estimated in 2023; and the latest 2025 projections. (Bear in mind that changes in market conditions between 2023 and 2025 have likely also contributed to changes in emission projections.)

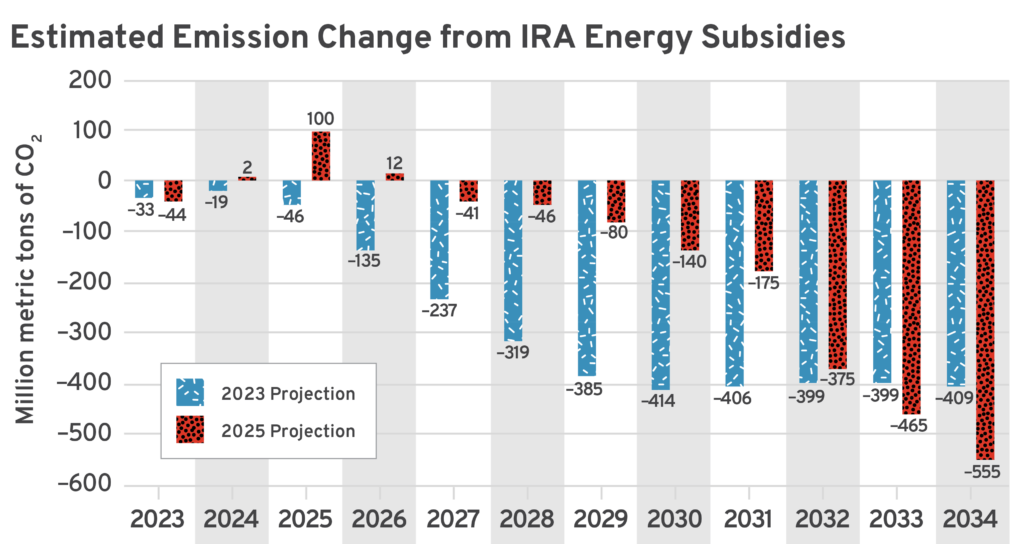

Recall, though, that the EIA substantially underestimated 2022 emissions, making it harder to extrapolate the IRA’s effect by simply comparing these baselines. The following chart attempts to isolate the effect of the IRA subsidies, showing the difference between the 2023 projections and the 2025 projections by demonstrating the additional emission abatement relative to the 2023 no-IRA scenario. Other changes in the EIA’s emission projections since 2023 (e.g., fuel prices, technology costs) can significantly affect emission projections; however, absent a 2025 no-IRA scenario update from EIA, we must rely on their 2023 projections.

The EIA initially projected in 2023 that the IRA would reduce cumulative CO2 emissions by 3.1 billion metric tons from 2025 to 2034 (relative to 2022 emission levels); under the updated data, this value has fallen to 1.8 billion metric tons. Importantly, 79 percent of that abatement is projected to occur in the last three years of the analysis window. This means that the majority of the IRA’s potential emission abatement is contingent upon the EIA’s accuracy regarding the medium- and long-term effects of IRA subsidies, despite their overestimation of the near-term effects.

Abatement Cost

To estimate the effectiveness of energy subsidies, it is useful to weigh the total cost of the IRA subsidies against the projected emission abatement. In this analysis, we take the estimated expenditure costs of the IRA-related subsidies—estimated in nominal dollars over a 10-year period—and apply that to the estimated emission abatement we consider attributable to the subsidies over the same period. These values offer a simple ballpark estimate of the IRA’s average abatement cost.

Alternative methodologies might look at lifetime emission effects and apply them to a discounted net-present cost of the IRA subsidies; however, due to data limitations and uncertainty of both costs and emission effects over the long term, we will not pursue those here. It is worthwhile to note, though, that projections of the lifetime cost of the IRA are exceptionally high, meaning that employment of such an analytical methodology should be anticipated to have a commensurately large abatement cost.

From a policy perspective, one could argue that abatement cost goes down over time as the emission gap between subsidy and no-subsidy scenarios widens. However, the cost of subsidies has risen in practice while the relative deployment of new clean energy and its opportunity to displace fossil fuels has fallen. This means that while some analyses may show lower abatement costs over longer projected timeframes, we can expect abatement costs to remain relatively high due to a steady reduction in marginal abatement opportunities amid the rising uptake of subsidies.

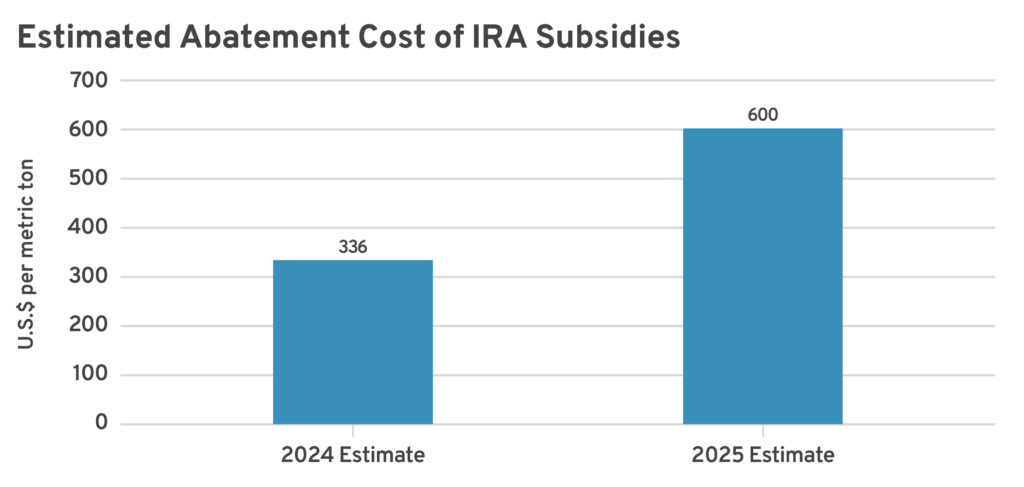

Overall, we estimate that if the IRA not passed, then climate-related energy subsidies over the 2025-2034 period would have been $124 billion compared to current-law projections of $1.2 trillion. We then compare this to the projected emission effects of the IRA from 2023 and to the most recent emission projections. Using 2023 emission projections, we would update the overall abatement cost of the IRA’s energy subsidies to $336 per metric ton of CO2; using the latest 2025 emission estimates, this value increases to $600 per metric ton.

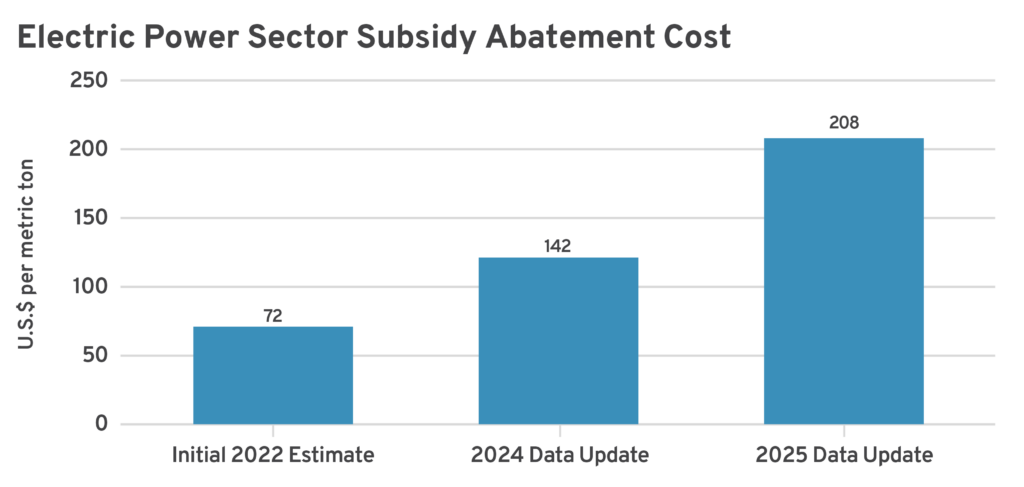

Importantly, the discrete abatement cost of IRA subsidies will vary significantly by sector, and while this is more difficult to determine owing to data limitations, we do have sufficient data to assess the electric power sector. When the IRA first passed, R Street estimated the abatement cost of subsidies in this sector would be, at lowest, $72 per metric ton. Rising subsidy costs and failure to meet emission targets have elevated the overall abatement cost of the clean-electricity subsidies. The following chart shows our initial estimate, an estimate combining the EIA’s 2023 projection of the IRA emission effects with 2024 subsidy expenditure projections, and the most recent estimate updated with 2025 emission projections.

Unconsidered Factors

While there are more complex methods for estimating abatement cost—as well as other factors to consider—we followed conventional methodology, which takes the direct cost (tax expenditure) and applies it to the estimated effect (emissions avoided). Had we included economic benefits, such as climate damage avoided or increased economic activity, those factors would depress the abatement cost. Alternatively, had we included the estimated economic effects from levying taxes to pay for the subsidies, the abatement cost would increase.

While it is outside the scope of this analysis to determine the magnitude of such effects, as a matter of economic principle we would anticipate that an econometrical evaluation of these policies (i.e., considering the interactive effects of taxes and subsidies on the economy) would result in a higher abatement cost. This is because as the value of the subsidies grows, so too does the anticipated “deadweight loss” to the economy from necessarily higher taxes.

In general, the potential positive economic effects of government subsidy are greatest during periods of high unemployment, which indicate a surplus of labor and lack of capital, and least effective when subsidies fail to induce additional entry of labor or capital to markets. Current economic conditions, in which unemployment is low and capital investments in clean energy were high even before the IRA, indicate that the subsidies are less likely to induce an economic benefit that outweighs the harm from private-sector losses of capital and labor elsewhere in the economy.

Overall, we acknowledge that this estimate is simply an approximation, given the narrowness of its variable consideration. It is intended for comparison against earlier estimates to determine whether the IRA energy subsidies are attaining their initially projected climate impact.

Causes of Rising Abatement Cost

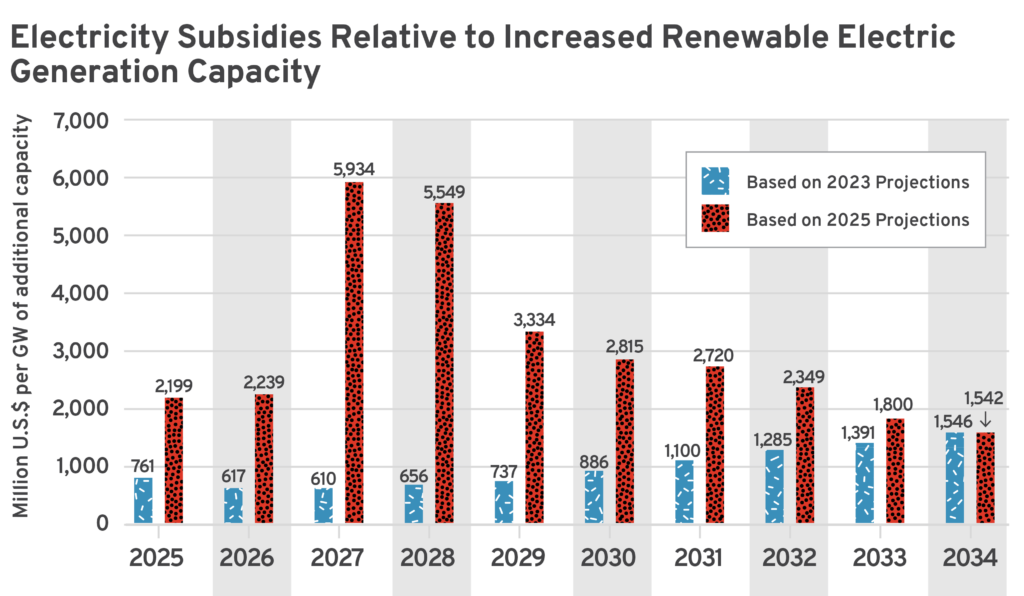

While there is little firm data on what steers investors to take up subsidies, we note that the overall subsidy expenditure relative to the market entry of new technology is rising as the increasing cost of subsidies relative to new clean-energy deployment is driven by both policy and market constraints. To illustrate this, we compare current-law Investment Tax Credit (ITC) and Production Tax Credit (PTC) expenditures relative to the projected additional renewable energy capacity attributable to the subsidies (i.e., above the no-IRA estimates).

The following chart shows the cumulative subsidy cost over the 10-year window relative to the cumulative additional renewable capacity attributable to the IRA subsidies. Both the 2023 and 2025 values use the same subsidy cost estimate (the Treasury Department’s FY2026 projections). The higher expenditures using the 2025 data reflect markedly lower projections of renewable energy capacity growth than in 2023.

The rising cost of electricity subsidies relative to new deployment is likely explainable primarily by permitting constraints and grid interconnection challenges—two of the most common reasons for canceling wind and solar electricity projects.

Another major explanatory factor is that much of the subsidy expenditure is being used to replace renewable energy, meaning that the net-capacity additions attributable to the subsidies are lessened. For example, almost half of new wind capacity added in 2024 was estimated to come from “repowering,” the process by which existing wind turbines are replaced with newer ones.

Policy Insight

Data updates reveal that the subsidies are underperforming compared to early projections. This is because earlier estimates of their emission effect largely relied on the assumption of capital availability as the constraining factor in clean energy growth, which is untrue. Permitting, grid interconnection, and power source characteristics are larger factors that govern the rate of clean-energy deployment and/or displacement of fossil fuels; however, eligibility is such that even projects with only slight emission effects can claim subsidies.

These factors combine to reduce the subsidies’ efficiency in stimulating emission abatement. From an environmental economics perspective, it is unlikely that IRA subsidies could carry enough environmental benefit to outweigh their cost to the public. From a climate policy perspective, the subsidies are encouraging inefficient deployment of technologies rather than valuing emission abatement, leading to a relatively high-cost climate policy compared to alternatives (e.g., permitting reform).

Conclusion

Data updates reveal that clean-energy subsidies expanded under the IRA have substantially underperformed. An abatement cost estimate is a product of policy cost relative to emission decline attributable to the policy. Pressure on both sides of that equation—rising costs and shrinking emission benefits—indicate that the abatement costs of subsidy-focused policies are rising. Future data updates are likely to reinforce this trend, as the estimates provided in our analysis rely on EIA projections that assume subsidy effectiveness over the long term despite inefficiency in the near term.

Overall, we believe that projections of the IRA’s efficiency in emission abatement and cost-effectiveness have likely overestimated its potential benefits and underestimated its costs. This is consistent with the conventional economic theory that subsidies are less effective at stimulating the market entry of new capital where barriers to entry are unrelated to capital availability.