State Permitting Challenges: Geothermal

New energy sources often face special regulatory challenges precisely because they are new. For an established energy source like oil, wind, or nuclear, the issues and points of controversy are largely known, and the regulatory system has been developed with the requirements of those sources in mind. An emerging energy resource, by contrast, is unlikely to fit neatly within any existing regulatory boxes.

While the theoretical potential of geothermal energy has long been known, it is only now beginning to come into commercial use on a large scale. Analysis has suggested that up to 90 gigawatts of geothermal electricity could be operational in the United States by 2050.

Geothermal producers take advantage of the heat emanating from the Earth’s molten core, using it as a source of power for heating and electricity generation. Geothermal energy is harnessed by drilling miles into the crust of the Earth, until temperatures are high enough to boil water and produce steam which can be used to run turbine engines.

The total amount of energy emanating from the Earth’s core far exceeds human needs. The main question for geothermal production, therefore, is whether this energy can be captured via technologically and economically feasible means.

Despite being a “clean” and “renewable” energy resource, geothermal projects still require extensive review and approval of permits from regulatory agencies to address possible environmental and other concerns. In terms of permitting, the geothermal production process most resembles oil and gas, though with some difference. State, local, federal, and sometimes tribal permits can be required for exploration, land access, leasing, drilling, and production. Some projects may require additional reviews and permits if located in an environmentally or culturally sensitive area. Finally, after the water extracted during geothermal production has been used, it must be reinjected underground, which requires its own set of permitting and standards.

While many aspects of the geothermal process are broadly similar to those for oil and gas production, the oil and gas industry has had over a century of experience in dealing with these requirements and has been granted waivers in some areas for some requirements. On the flip side, geothermal may not provoke as much public or interest group hostility as oil and gas projects because the energy source does not involve substantial greenhouse gas emissions or the emission of other types of emissions. However, geothermal projects can still provoke opposition, particularly if the companies involved have also been connected to fossil fuel production.

Because commercialization of geothermal energy at scale is still in the early stages, there is less quantitative data to draw on to identify which aspects of the permitting process are most challenging. That said, analyses have flagged several issues that are likely to result in delays.

State-based vs State-specific Challenges

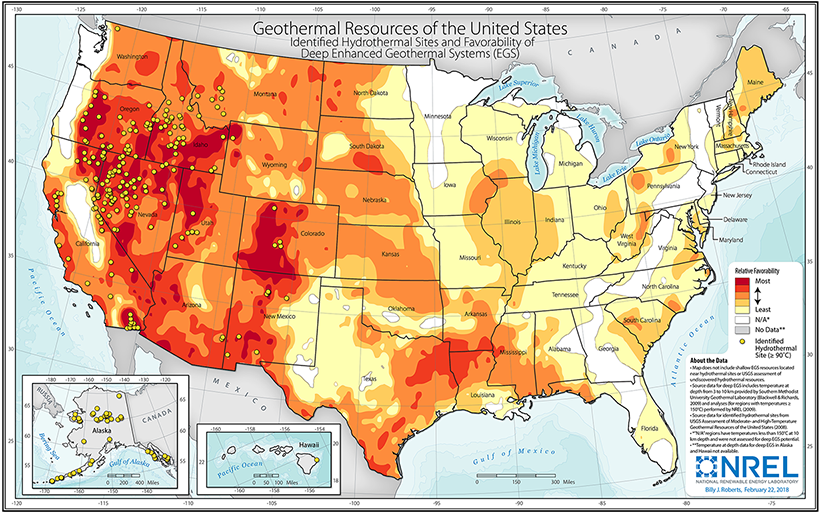

While all geothermal energy ultimately derives from the Earth’s core, that energy is not equally accessible from all parts of the Earth’s surface. In general, it is easier to tap into geothermal energy in the western United States because of differences in the thickness of the Earth’s crust and the location of tectonic plates.

Source: National Renewable Energy Laboratory

This can create some special challenges for geothermal energy production as geographical considerations that make permitting more complicated are more prevalent in some parts of the country. A significantly greater proportion of land in western states is federal land. Though approximately 26 percent of U.S. territory is federal land, in the seven states with active geothermal power plants (California, Hawaii, Idaho, New Mexico, Nevada, Oregon, and Utah), federal land comprises an average of 45 percent of land. This can create additional layers of permitting complexity. For example, in Nevada geothermal projects located on federally managed land must get drilling permits from both the federal Bureau of Land Management and the Nevada Division of Minerals.

Other issues can also complicate the permitting process. For example, permitting tends to take longer and be more costly to complete when the project implicates wildlife concerns, such as when it is in the habitat of an endangered or threatened species, or otherwise impacts biological resources. Research has found that the median environmental assessment takes 69 days longer to complete if it involves endangered species and 177 days longer to complete if it involves migratory birds. This is an issue for geothermal, as some of the western states with the greatest geothermal potential also contain a large number of environmentally sensitive areas. California, for example, ranks second in the number of listed species as threatened or endangered under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) within its territory, at 292.

Another issue that can cause delays is if the project is in an area that implicates cultural resources. Environmental assessments take an average of 81 days longer to complete for projects that implicate tribal concerns. As with endangered species, tribal areas are more common in the western states where geothermal potential is highest.

Longer timelines can significantly add to the cost of geothermal projects. One analysis of projects in several western states found that the levelized cost of electricity was 4-11 percent higher for projects with longer California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA)/National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) review timelines than for projects with the fastest CEQA/NEPA review timeline. This translated to a loss of $64-227 million in revenue on a net present value compared to what the developers could have otherwise generated if the project could be reduced to the fastest review timeline.

However, the fact that these are state specific does not necessarily mean that they are state based, in the sense that there are not issues with state-level permitting but rather with other issues that are more pronounced in some states. For example, projects in a particular state may be more likely to raise concerns under the ESA, but these are still federal issues, though some states do have their own state-level process for addressing wildlife concerns.

Permitting Redundancy

A key state challenge for geothermal is the need to obtain permits from multiple agencies that often have different standards and overlapping jurisdictions. Projects in Imperial County, California must receive permits from 11 different state and local agencies, apart from any federal or other processes that may be required.

Some states have developed a more streamlined system for geothermal permitting. In California, projects with an installed capacity of 50 megawatts (MW) or more can use a single Application for Certification process through the state’s California Energy Commission. This process allows permitting to be handled mostly through a single agency and includes statutory mandated processing time limits to reduce delays. Projects of less than 50 MW, however, must still go through the more cumbersome, multi-agency process. Of active geothermal plants in the United States, only around one-third have a capacity of 50 MW or more, suggesting that a lower threshold could help with project completion.

Additionally, where both state and federal permits are required for a project, it may be possible to decrease the time necessary to complete permitting through better coordination between agencies and formalized memoranda of understanding to reduce uncertainty in the process.

Conclusion

The geothermal energy footprint in the United States is still fairly small. As such, there is limited data upon which to draw conclusions about the effect of state-permitting processes on geothermal development. What data exists suggests that key challenges may reside in other areas, such as the interaction of projects with federal or tribal lands, or with federal laws such as the ESA. Nevertheless, there are ways in which state-level permitting could be simplified to reduce project cost and timeliness without compromising environmental or other concerns.

Series: State Energy Infrastructure Permitting and Siting

Meeting electricity demands over the next few decades will require substantial infrastructure expansion throughout the energy sector. This new series surveys the challenges state and local permitting requirements pose to new energy infrastructure.