Possible Modifications to IRA Subsidies That Would Reduce Taxpayer Liabilities While Retaining Climate Benefits

Key Findings

- Modifying most IRA clean energy subsidies to be repealed starting in 2028 would still retain 66 percent of the estimated emission benefits of those subsidies.

- Such modification would save approximately $771 billion over 10 years.

- Most clean energy subsidies are extraordinarily high-cost in their current form, creating substantial opportunity for modification to improve efficiency.

Introduction

Republicans have expressed interest in repealing elements of the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). This may be an attractive option for funding other priorities (e.g., tax cut extension), but because Republican constituents also benefit from IRA subsidies, repeal or modification of such subsidies may be politically challenging. As a historical example, despite Republican opposition to clean energy subsidies, the Republican-led 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act did not substantially modify them.

The U.S. Treasury Department estimates the total expenditures and outlays of relevant IRA climate-related tax-based subsidies to be $1.2 trillion over the fiscal year (FY) 2025-2034 period—much greater than the initial estimate of $270 billion. Despite the political appeal of clean energy subsidies, Congress likely will be under increased pressure to reduce IRA costs, especially to pay for tax cut extensions set to expire this year.

To this end, we feel it is worthwhile to outline a policy proposal that could capture substantial revenues while maximizing environmental benefits. The following analysis details a proposal that could balance these objectives. What we call the “Innovation 28 (I28)” proposal would partially repeal IRA subsidies. The most expensive and least beneficial subsidies are repealed under I28, while subsidies for innovation and early-stage technologies would be retained. Such a policy would retain most of the potential emission benefits of the IRA while substantially reducing the overall cost to taxpayers.

I28 Proposal

I28 aims to reduce the level of government subsidy expended while maintaining potential innovation benefits by sunsetting any subsidy that is unlikely to deliver significant environmental gains. It also incorporates two legislative proposals from past Congresses. The first is the Energy Sector Innovation Credit Act (ESIC), which would replace most existing energy-related subsidies starting in FY 2028. ESIC functions much like current clean electricity subsidies, except with much narrower eligibility criteria (available only to early-stage technologies accounting for less than 3 percent of electricity production). This preserves subsidies considered important for innovation while eliminating subsidies for mature technologies that do not need them to be competitive in the market. The second is the Carbon Removal and Emissions Storage Technologies Act (CREST), which aims to incorporate competitive mechanisms into carbon capture subsidies.

Other subsidies would be sunset after FY 2027. The form of sunset for relevant credits is full credit for FY 2025-FY 2027 and full repeal for FY 2028 and beyond. A simple overview of I28 is as follows:

- Retain production tax credit (PTC) and investment tax credit (ITC) for FY 2025-FY 2027.

- Beginning in FY 2028, replace PTC and ITC with ESIC, ending subsidies for new onshore wind and photovoltaic (PV) solar facilities while retaining subsidies for immature low-carbon electricity generating resources.

- Beginning in FY 2028, return the 45Q carbon capture credit to its pre-IRA form and establish a new carbon capture subsidy program modeled after the CREST Act, with an additional $300 million reverse auction for carbon dioxide removal for FY 2028-FY 2034.

- Retain all other subsidies (e.g., domestic manufacturing, electric vehicles, clean fuels, residential energy efficiency) for FY 2025-FY 2027; repeal for FY 2028-FY 2034.

In short, I28 modifies an estimated $1.2 trillion in clean energy subsidies. The proposed plan would retain subsidies for early-stage technologies and eliminate subsidies for mature technologies beginning in FY 2028. This is key because the highest cost, least effective subsidies go toward resources that would be built anyway while the technologies that could benefit most from subsidies remain nascent.

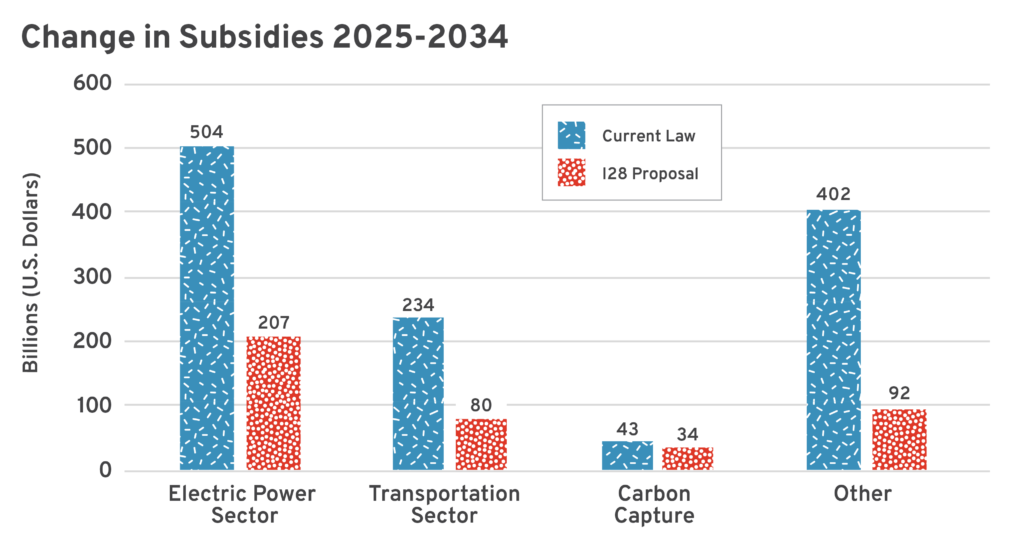

The following chart shows the current-law cost of climate-related subsidies by sector compared to what each sector would receive under the I28 proposal.

While this analysis assumes that the Treasury’s estimated costs of these tax credits equal the potential revenue gained from their repeal, the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT), which is responsible for producing revenue estimates from legislative proposals, may estimate either more or less revenue when accounting for the interactive effect of affected policies. For example, if a taxpayer is eligible for two mutually exclusive tax credits—one $100 and the other $50—the estimated tax expenditure from the tax credit is $100. If the $100 credit is repealed, the taxpayer will claim the $50 credit for a revenue gain of only $50—not the $100 value of the repealed credit. Ultimately, it is up to JCT to give an official revenue estimate; in the interim, we will use the Treasury’s values as a substitute.

We do have some insight as to the potential accuracy of the Treasury’s estimates, thanks to a leaked memo from the U.S. House of Representatives Budget Committee that estimated $796 billion of potential revenue from repealing “green energy tax credits,” as well as $404.7 billion of revenue from repealing other energy-related provisions of the IRA. If these provisions are additive, the value would be $1.2 trillion, or roughly the same as the Treasury’s. However, the leaked memo does not provide clarity on precisely which provisions are included in each estimate. This makes a direct comparison to the Treasury’s estimates impossible.

Electric Power Sector

Most subsidies in the electric power sector go to onshore wind and PV solar. The EIA estimated that, in FY 2022, 85 percent of the PTC went to onshore wind while 100 percent of the ITC went to PV solar. These subsidies increase as time goes on and as more eligible claimants enter the market. Treasury Department estimates for the 2025-2034 period are $304 billion for the PTC and $138 billion for the ITC.

The I28 proposal reduces the cost of electric power sector subsidies by approximately $297 billion over the 10-year period. The reduced cost results almost entirely from decreasing subsidies for onshore wind, PV solar, and existing nuclear power plants. Note that a certain amount of the PTC cost (which mostly goes to onshore wind power) should be considered baked in, as eligible facilities can claim credit for up to 10 years after entering service. While Congress could technically modify the PTC to eliminate eligibility retroactively, it is not a commonly proposed policy.

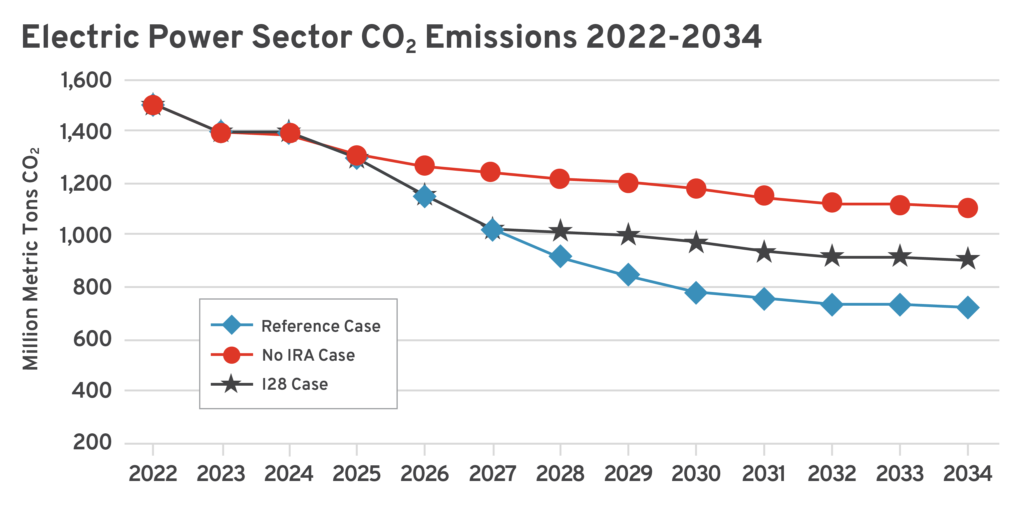

This proposal also retains most of the IRA’s potential emission benefits in the electric power sector. This is because subsidies have a greater impact in earlier years than later ones. So even though subsidies are reduced dramatically for seven out of 10 years of the budget window, 61 percent of anticipated emission abatement in the electric power sector stems from clean energy entering the market during the first three years.

Utilizing data from the EIA (which modeled emission outcomes without the IRA as part of its 2023 Annual Energy Outlook), we see that the IRA could deliver a cumulative emission reduction of 2.9 billion metric tons of CO2 from 2025 to 2034; compared to the no-IRA scenario, I28 still achieves a cumulative 1.8 billion metric ton emission reduction.

However, the EIA’s estimation of emission benefits from the IRA is potentially overstated. It is unclear to what extent their modeling sufficiently accounted for emerging barriers to market entry that are unrelated to access to capital. If the EIA overestimated the subsidies’ benefits, then that would lessen the difference between retaining them or sunsetting them.

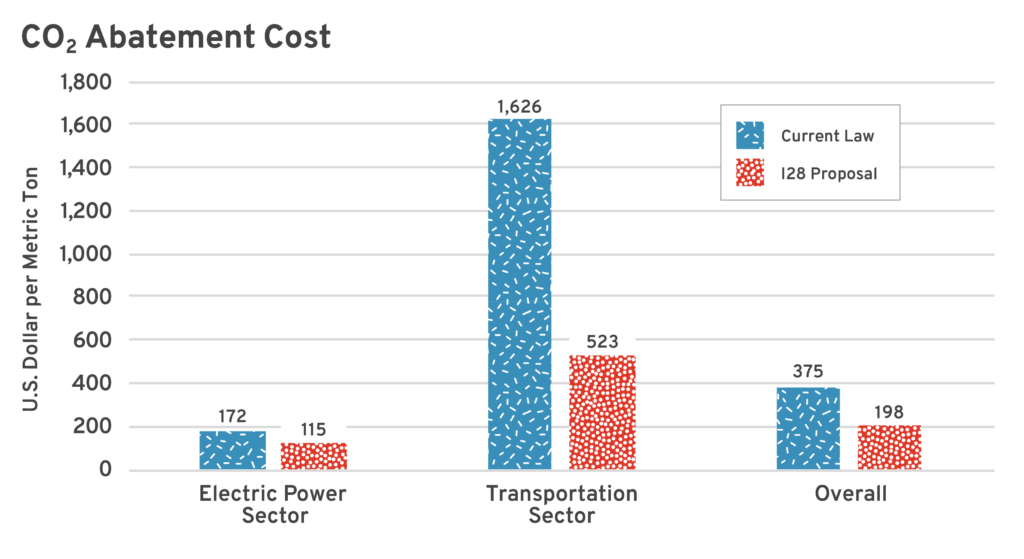

By combining the total costs and potential CO2 emission abatement estimates based on EIA data, we can estimate an abatement cost of the relevant tax credits, expressed as their total cost over the 10-year period compared to the CO2 emission change from the baseline. This would differ from the marginal cost to abate one ton of emission in that we are estimating what the government pays rather what an emitter would pay to reduce emissions by this amount.

We count $504 billion of electric power sector subsidies under the current law case, giving an abatement cost of $172 per metric ton. Electric power subsidies under I28 would cost $207 billion, giving an abatement cost of $115 per metric ton (roughly 33 percent lower cost per metric ton of CO2).

Transportation Sector

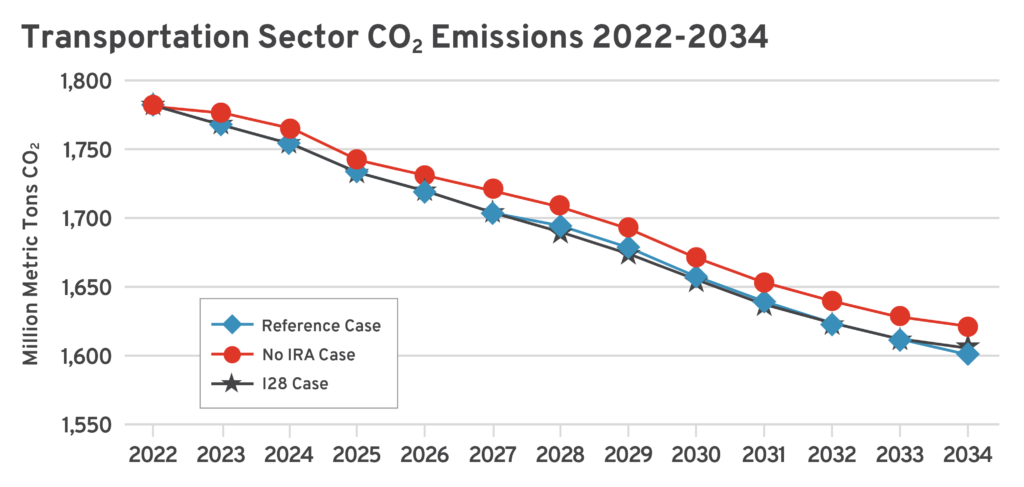

Although the IRA contains several transportation-related subsidies, this analysis focuses on subsidies for clean electric vehicles, low-carbon fuels, and refueling properties. The I28 proposal phases these credits out entirely beginning in FY 2028.

The IRA’s transportation-related subsidies are extremely inefficient at abating emissions. Under current law, transportation-related climate subsidies are expected to cost $234 billion; the I28 proposal would reduce that amount to $80 billion. The high cost of transportation-related subsidies is largely a product of their intent to affect large capital purchases rather than their potential impact on emissions. Additionally, we anticipate a large uptake of electric vehicles and clean fuels even without the IRA subsidies, making them less effective compared to scenarios that include their repeal. The following chart shows the difference in emissions with and without subsidy modification.

The inefficiency of transportation-related clean energy subsidies in modifying emission outcomes also increases cost. Relevant subsidies currently cost approximately $1,626 per metric ton of CO2 abated; I28 would reduce this cost to $523 per metric ton while capturing approximately the same emission abatement as the current scenario, since most of the subsidies’ potential benefits are concentrated in their early years. In total, the I28 proposal would reduce the abatement cost of transportation-related subsidies by approximately 68 percent.

Overall Effects

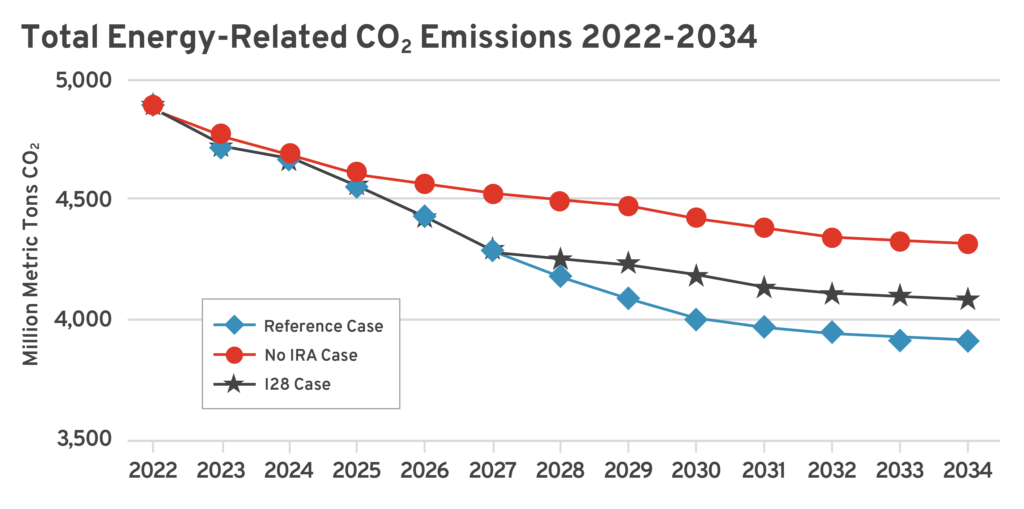

I28 would substantially reduce the cost of clean energy subsidies while retaining most of their benefits. Compared to the current-law subsidy cost of $1.2 trillion, the I28 proposal would cost $412 billion—a savings of $771 billion. Because the I28 proposal retains incentives for near-term deployment of clean energy-related resources, it also retains most of the overall emission benefit. The following chart shows an estimated emission trajectory that assumes early presence of subsidies with phase-out beyond FY 2027.

The EIA estimates that the current-law scenario (i.e., no modification to the IRA) would reduce energy-related CO2 emissions over the 2025-2034 period by a cumulative 3.2 billion metric tons. Meanwhile, we estimate that I28 would result in cumulative energy-related CO2 emissions that are 2.1 billion metric tons below the no-IRA scenario. The proposal would reduce overall energy subsidy cost by $771 billion while retaining 66 percent of emission benefits, which would reduce the overall abatement cost of clean energy subsidies from $375 per metric ton to $198 per metric ton.

Analytical Constraints

In practice, I28’s total cost would likely be higher than stated here for a few reasons. One is that when tax credits expire, we see a certain volume of activity shift earlier to capture the tax credit (e.g., people buying electric vehicles before the tax credit runs out). The proposal does not estimate that effect. Another reason is that eliminating subsidy for conventional wind power while retaining subsidy for newer technologies may shift activity to those sectors. Our proposal does not model this. Lastly, I28 bases the future PTC cost on its added eligible generation while in reality, we have seen much of it go toward “repowering” existing renewable energy facilities. The PTC’s total cost may increase if such activity is permitted for FY 2025-FY 2027.

Additionally, these estimates are based on limited data reported by the government rather than modeled econometrically. This means there are other constraints that can be difficult to adjust for, such as the fact that tax expenditure data is reported in fiscal years while energy production and emission data is reported in calendar years. We expect that if Congress’s JCT and/or the EIA were to model these same policies, they would report different results.

That said, we expect the cumulative effect of these challenges to be modest relative to overall estimates. We believe I28 offers a sufficiently accurate “ballpark” estimate that can inform Congress of the approximate magnitude of reduced government spending from their approach to modifying relevant tax credits.

Conclusion

While we do not expect Congress to adopt the I28 proposal, the plan illustrates how modified subsidies can retain most environmental benefits and maintain pro-innovation energy policy priorities at far lower cost. Overall, I28 shows that a cost reduction of over half a trillion dollars in clean energy subsidies can be achieved in a manner that avoids near-term disruption to energy investment while retaining substantial portions of the estimated environmental benefits the IRA could have captured.