How Do We Measure What Congress Has Accomplished?

With approval ratings somewhere below Nickelback and root canals, Congress is hardly America’s favorite institution. The American public certainly seems to view gridlock and shutdowns dimly, and there’s a popular notion that the best measure of whether Congress is doing its job is whether it’s passing a large number of laws. “More laws good; fewer laws bad,” according to this view.

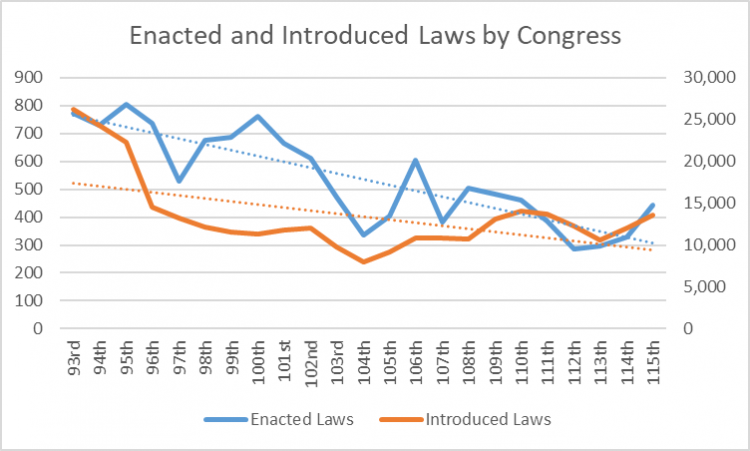

That framing might not be accurate – more on that later – but the number of enacted and introduced laws has certainly trended downward over time.

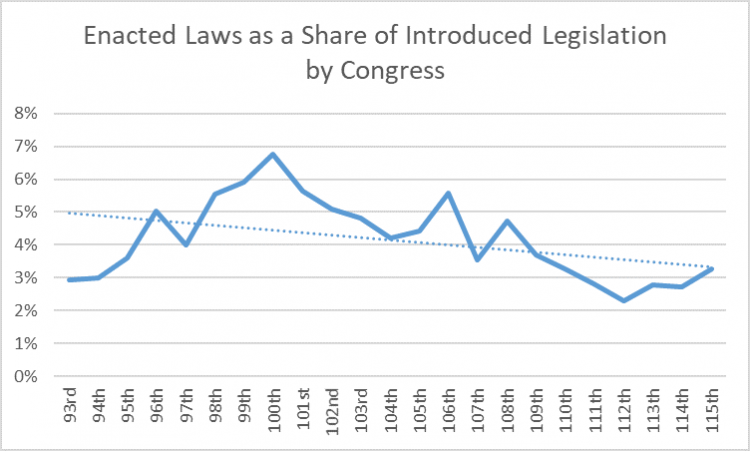

The same trend holds if you look at enacted legislation as a share of bills introduced. After peaking at nearly seven percent in the late 1980s, only between two to four percent of bills have ultimately passed in recent years. Schoolchildren might need to have their lessons updated.

Some see this trend as evidence that lawmakers are less committed to crafting winning legislation than in years past, while others view it as an unsurprising side effect of partisanship and increased polarization. Of course, there are many ways to assess legislative accomplishment, and the raw number of bills passed is only one. Few would characterize Congress as productive were all those bills merely renaming post offices and federal buildings.

An alternative approach is to examine the key pieces of legislation that Congress is passing. Whether one thinks legislators are accomplishing good or bad things is largely in the eye of the beholder, but a large budgetary impact in one direction or another can give a sense of how Congresses compare with one another.

What are we to make of Congress so far during the Trump presidency? One way is to consider recent Congresses.

Under this framework, the most consequential bill signed into law during this session has been the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2019, which raised federal budget caps for two consecutive years and effectively increased federal spending by nearly $300 billion during that time. Indeed, the member rankings on SpendingTracker.org, which tracks all legislative votes for new spending, correlate heavily with whether a representative voted for or against that legislation.

H.R. 3877: The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2019

Congress also approved, and the President signed, the new defense authorization for 2020 that dramatically increased Pentagon spending. S. 1790, the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020 raised federal spending by about $44 billion over the previous year.

Other legislation of significant consequence during the last year-and-a-half, includes primarily omnibus and supplemental appropriations bills, the most recent of which is H.R. 6074, the Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act of 2020. (For a complete list of the budgetary impact of legislation signed into law this session, see here.)

The last three-plus years have seen substantially bigger government when compared to the divided composition that characterized the early 2010s. And there can be no denying the unprecedented increase in the federal debt during a time of strong economic growth.

How does this compare to previous Congresses? The table below summarizes Spending Tracker data from sessions of Congress since the start of the Obama Administration.

| Congress | President | Congress | New Spending |

| 111th | Obama | Democratic | $2,181,809,000,000 |

| 112th | Obama | Split | $348,027,840,000 |

| 113th | Obama | Split | $105,712,660,000 |

| 114th | Obama | Split | $715,566,720,000 |

| 115th | Trump | Republican | $579,648,820,000 |

| 116th | Trump | Split | $423,983,010,000 |

Source: SpendingTracker.org

Obviously this is not a perfect way of comparing Congresses, because it depends, among other things, on the set of legislation for which the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) ultimately provides estimates. That said, CBO maintains a standardized process for scoring legislation, and it’s probably reasonable to assume that most major pieces of legislation ultimately received an official estimate.

Right away, a few observations stand out.

The first is that by far the biggest-spending Congress in the last 12 years was that in office immediately after President Obama took office. This shouldn’t be surprising, given that the wake of the financial crisis saw the passage of the stimulus package, Obamacare, and CHIP reauthorization, in addition to the usual big defense bills and other appropriations.

The second observation is the dramatic decline that took place in the middle part of Obama’s time in office. This makes sense, too, given the passage of the Budget Control Act of 2011, which contributed to a decline in total government spending in back-to-back years for the first time since the Korean War.

Much like the political climate of the mid-1990s, the combination of a Democratic president and a Republican Congress resulted, perhaps not in a balanced budget, but definitely in a period of robust economic growth and restrained federal expenditures.

What’s also clear, however, is that we no longer live in those times.

In the latter years of the Obama presidency and the early years of Trump, the “Ryan-Murray” Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013, the “Obama-Boehner” Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015, and the “McConnell-Schumer” Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 all paved the way for more spending.

This trend culminated most recently with the “Pelosi-Mnuchin” Bipartisan Budget Act of 2019 discussed earlier, but there’s no doubt that increases to federal expenditures were already well underway by the end of Obama’s second term in office.

Republicans may claim that united Republican government will lead to more responsible spending and balanced budgets, but as Congress under President Trump has shown, the evidence is unfortunately mixed at best.

The 115th Congress certainly looks better than the 111th, which was united with Democrats in control. Of course, those were very different times, with the federal government––rightly or wrongly––imposing emergency measures in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. No such crisis existed at the start of the Trump presidency.

How one interprets this Congress’s legislative record will likely depend on one’s assessment of the bills that end up signed into law. What’s clear, though, is that even as fewer laws are passed, Congress remains adept at finding creative ways to spend on priorities old and new.

In that respect, history ultimately may judge the 116th as more efficient than its predecessors of years past. Whether that efficiency leads to better outcomes, however, is another matter altogether.