From Victim to Defendant: How Justice Falls Short for Women

Authors

Table of Contents

- Executive Summary

- Introduction

- Women as Victims

- Women as Defendants

- Victims as Defendants

- Conclusion

Media Contact

For general and media inquiries and to book our experts, please contact: pr@rstreet.org

For decades, the justice system has failed to recognize how deeply intertwined women’s victimization and criminalization are. A serious response requires policies that account for trauma, economic instability, relational dynamics, health differences, and other factors that drive many women into the system.

Executive Summary

Far too often, when a woman meets the justice system, it is first as a victim of violence and later as a defendant charged with criminal activity. As victims, it is not uncommon for women to find their voices lost in the criminal justice discussion. As defendants, relevant context, including trauma, coercion, and the fight to survive, is rarely considered in courtrooms—especially in cases of self-defense, substance misuse, and human trafficking. This lack of acknowledgment leaves women doubly failed: They are denied justice when harmed, and they are punished harshly if victimization later shapes their actions.

The rapid increase of women in the justice system over the past 40 years has exposed how poorly equipped current policies are to respond to the realities of women’s experiences and specific needs. Traditional reforms have focused on men in the justice system, overlooking that women’s pathways into the system are frequently rooted in abuse, caregiving pressures, and economic instability. By failing to recognize the distinct needs of women, the system has expanded incarceration without improving public safety or addressing the underlying drivers of women’s involvement in the justice system.

This policy paper explores women’s involvement with the justice system in three primary contexts: as victims, as defendants, and as both. Across these forms of justice system involvement, common themes emerge: low reporting and conviction rates for gender-based violence; rising rates of female incarceration tied to poverty, substance misuse, and punitive policies; and persistent issues in offering effective approaches for victim-defendants (i.e., those whose criminal behavior stems from abuse). The result is a system that broadly fails to deliver safety, fairness, or legitimacy.

Key Policy Recommendations:

• Strengthen victims’ rights and recourse by enacting notification laws, guaranteeing rights to proceedings, training system practitioners in trauma-informed approaches, and expanding the availability of victim-centered alternatives to prosecution

• Improve justice for female defendants by integrating gender-responsive programming and reentry practices, providing access to gender-specific health supplies and services, adopting clear policies and oversight around pregnancies, and investing in specialized courts

• Protect and support victim-defendants by granting victim immunity, passing survivor justice laws, adjusting mandatory arrest laws and laws meant to prevent sexual abuse in carceral settings, and training criminal justice professionals in trauma-informed practices

Introduction

For most of American history, the criminal justice system was built by and for men. That design reflected the simple reality that men have long been—and remain—the most significant perpetrators of crime. Over the last 40 years, however, these demographics began to shift, and women moved from the margins to a growing share of defendants. Today, nearly 1 million women are involved with the U.S. criminal justice system. Unfortunately, this increase in justice-involved women has collided with an infrastructure unprepared to meet their needs. In most cases, the rules, routines, and assumptions established for justice-involved men were automatically applied to women’s correctional facilities, despite the presence of gender-specific differences that warrant specialized approaches. Although “gender-responsive correctional practices” began appearing in the 2000s, research on women’s pathways into the system remains outdated, and research on how the system can support them is limited.

Meanwhile, the voices of victims have faded in today’s criminal justice reform conversations. Current debates tend to focus on incarceration and the defendants’ rights, with less emphasis on violence prevention or meaningful justice for those who have been harmed. Indeed, for many women, victimhood and criminality are not separate conditions, but overlapping realities.

This tension between victimhood and criminality hangs over the justice system, as it draws in more women, protects fewer women from harm, and rarely acknowledges that these individuals are often one and the same. This paper examines the role of women in crime and justice as victims, as defendants, and as both. It also assesses blind spots in criminal justice policy that disproportionately impact incarcerated women and suggests targeted policy solutions to support and protect women more effectively while simultaneously addressing the rising involvement of women in criminal activity.

Women as Victims

Women experience violence at alarming rates, but their experiences are often unreported, misunderstood, or underserved by the justice system. Intimate partner violence (IPV)—which includes crimes like sexual assault, domestic violence, and stalking—disproportionately affects women, with rates of reported sexual violence and stalking nearly triple those reported by men. Some studies suggest that one out of every two women will experience IPV in their lifetimes, and women account for more than one-half of all violent crime victims. The majority of these incidents never reach a courtroom.

Barriers to Reporting and Seeking Justice

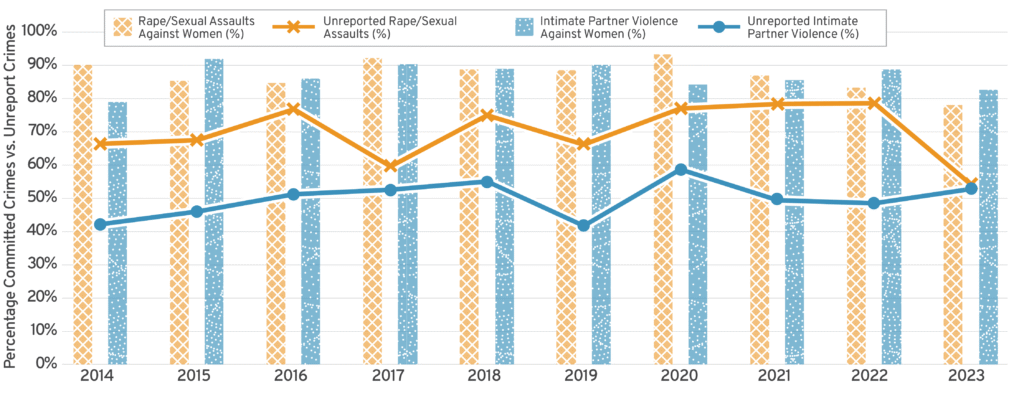

Often, female victims feel that the justice system fails to provide meaningful outcomes, which contributes to rates of underreporting. As Figure 1 shows, approximately one-half of violent crimes and two-thirds of rape cases—in which women are disproportionately victims—go unreported. Victims choose not to report violent crimes for a variety of reasons, including believing police would not be helpful, fearing retaliation, or thinking the offense should be addressed outside of the criminal justice system. Concerns about police response are particularly strong in cases of sexual or domestic violence, where victims often anticipate dismissal or re-traumatization by law enforcement.

Figure 1: Female Victim Rates and Reporting in Sexual Assault and Intimate Partner Violence

For many victims, seeking justice is not primarily about punishment. Most do not expect the offender to receive a lengthy sentence, nor do they think such sentences are the most effective form of justice. Rather, they come forward with the hopes of stopping the offender’s behavior and preventing harm to others. Victims are typically seeking concrete rehabilitative steps like counseling, addiction treatment, relationship or emotional regulation classes, restitution, or a genuine apology.

This desire to rehabilitate and educate makes sense on a societal scale, as the vast majority of those convicted of a violent crime will eventually return to their communities. Like the public as a whole, victims want to ensure that when the offender does so, they have changed for the better and will not reoffend. Some victims may also prefer alternatives to traditional prosecution because they seek healing, empowerment, or safety over punishment—particularly when the justice system feels re-traumatizing or fails to meet their needs.

When victims do report violent crimes to the police, the likelihood of achieving justice remains low. Although research is limited, available studies suggest that sexual assault and domestic violence cases experience high attrition rates—meaning cases are often declined for prosecution or dismissed. One recent study from eight major cities shows that fewer than 4 percent of sex crime cases result in convictions. Moreover, the legal process for these cases often stretches over months or years, during which time victims must repeatedly recount their traumatic experiences in courtrooms or interviews that are designed to dissect and challenge every detail of a victim’s story rather than support recovery. Victims often experience invasive questioning about their behavior, history, and motives. Such scrutiny deters reporting because it delays and complicates emotional recovery.

Importantly, the perception that women frequently fabricate IPV claims is not supported by evidence. Rates of false allegations of IPV are extremely low, as the moral weight and legal risk of filing a false report act as powerful deterrents, and false reports rarely get far in the prosecution process. Yet legitimate allegations also face steep barriers. An inherent challenge is the private nature of most IPV, which typically occurs behind closed doors, without witnesses or clear evidence. These dynamics often trigger deep-seated, bias-laden questions among police, prosecutors, and jurors that shift blame from the perpetrator to the victim: Why didn’t she leave? Why didn’t she fight back? Why was she there in the first place? As a result, victims are required to recount painful and deeply personal experiences to a series of strangers—police officers, prosecutors, judges, and juries—while investigators and defense attorneys comb through their personal histories, expose private details, and work relentlessly to discredit testimony. Even worse, scrutiny often continues outside of the courtroom; for example, a recent study found that one in four social media comments on IPV articles fell into the category of victim-blaming. Few would endure this experience for the sake of a fabricated claim.

Systemic Gaps and Long-Term Impacts

The criminal justice process itself can compound trauma. Victims are often flooded with information immediately after reporting a crime—while still in shock—yet left uninformed about key proceedings, plea negotiations, and outcomes as cases progress. Even in states with strong victims’ rights laws, protections frequently fail in practice because of weak enforcement and a lack of meaningful representation to help victims assert them. For example, some jurisdictions do not require that victims be notified of hearings involving bail, protective orders, pleas, or sentencing, instead offering only general or delayed updates. Others are required to provide notification, but lack a consistent and effective process for doing so. Even when rights are codified, victims frequently remain unaware of them because of minimal outreach, lack of plain-language materials explaining the process, and an absence of systematic procedures for informing them at critical stages. As a result, victims often face these complex systems alone, with little recourse when they fail.

When the justice system falls short in these ways, victims may face long-term, compounding health, financial, and social challenges, which can further entrench cycles of dependency, vulnerability, and system involvement. Inadequate access to support and services, such as crisis counseling, legal aid, and medical resources, is a particular problem in rural and underserved areas. These types of services are critical, as victims commonly experience post-traumatic stress disorder and other serious mental health conditions. Victims of IPV may also experience employment instability, which increases their risk of declaring bankruptcy, having a life-threatening illness, or having a disability or chronic illness.

The cumulative effect is a justice system that fails the very people it is meant to protect. With low conviction rates, long and painful legal processes, and limited support, many women find that coming forward carries more cost than staying silent. Recognizing these systemic shortcomings is the first step toward creating a more responsive and accountable framework.

Policy Recommendations

Policymakers should prioritize approaches that enhance victim safety, uphold victim dignity, and expand meaningful choices in how justice is pursued. In addition, system actors—from police to prosecutors to court staff—should be empowered to handle interactions with victims responsibly and productively and hold perpetrators of IPV accountable for their actions. We recommend the following:

• States should enact clear, enforceable victims’ rights laws. This includes laws that guarantee timely notification of all meaningful proceedings, proactively inform victims of their rights from the outset (including to be present and heard), and provide access to legal remedies when these rights are violated (e.g., victims’ rights attorneys, qualified advocates). Without these structural supports, victims’ rights risk being symbolic rather than substantive.

• Courts should implement opt-in email and text notification systems that are clearly communicated to victims and easy to access. Notification systems complement existing platforms like VINE (Victim Information and Notification Everyday) by updating victims on hearing dates, continuances, plea agreements, and sentencing, helping them to engage with the justice process. Expanding notifications across all courts and delivering them through easy-to-use formats like text messages ensures that victims have the information they need to engage meaningfully in the justice process. Law enforcement and the courts should work together to inform victims about court notification systems and provide straightforward, timely ways to enroll.

• All law enforcement officers, prosecutors, and judges should receive mandatory, ongoing training in trauma-informed practices and victim-centered approaches. Trainings should cover the neurobiological effects of trauma, common victim behaviors that may seem counterintuitive (such as delayed reporting, inconsistent statements, or continued contact with offenders), and evidence-based techniques for conducting respectful interviews and interactions. Justice professionals can avoid re-traumatizing victims by understanding how trauma affects memory, decision-making, and behavior, while building stronger cases and maintaining the integrity of the legal process.

• States should expand the availability of victim-centered alternatives to prosecution. Restorative justice approaches, such as victim-offender mediation or community conferencing, offer structured, voluntary spaces for dialogue, accountability, and repair. Programs should be made available pre-charge and with prosecutor approval for appropriate cases, and victims should be offered the option of such approaches. Participation must be voluntary for all parties, and victims should retain the right to pursue formal prosecution. Programs must be staffed by trained facilitators and follow strict safety protocols.

• Lawmakers should embed victim voices and protections in reforms and core procedures. Too often, reforms prioritize efficiency or defendant-focused changes while overlooking the needs of victims. Lawmakers should ensure that victims’ rights are built into the structure of criminal justice reforms and adopt safeguards to protect against re-traumatization and coercion (e.g., limiting defense subpoenas in early-stage hearings and redacting victim identities in publicly released camera footage) to enhance procedural fairness and strengthen trust in the system for all parties.

Women as Defendants

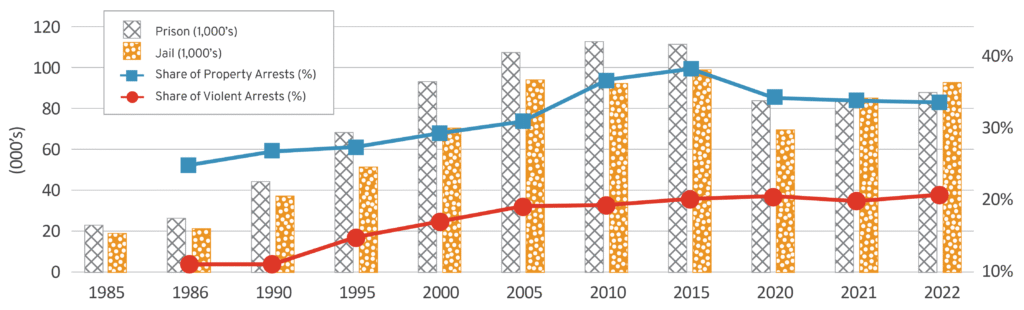

Over the last several decades, women have been the fastest-growing population in the criminal justice system. As shown in Figure 2, the incarcerated female population has tripled since 1985, doubling the growth rate seen among men. Arrest trends mirror this rise. In 2019, female arrest rates for violent crimes were 63 percent higher and for drug crimes 317 percent higher than they were in 1980. By the early 2020s, nearly 1 million women were involved in the criminal justice system.

Figure 2: Women’s Involvement in the System (Incarceration)

Research consistently shows that women commit fewer crimes than men, particularly violent offenses. One factor that may help explain this disparity is the earlier development of social cognitive skills in girls, which supports stronger prosocial behavior. Studies suggest that girls benefit from a combination of biological and social influences, such as more effective brain communication and greater verbal ability. These skills not only reduce the likelihood of early antisocial behavior but may also buffer against its escalation into more serious criminal activity.

Women’s Pathways into the Justice System

Pathways into the justice system often look different for women than for men. While men are more likely to commit violent offenses and engage in organized criminal activity, women’s offenses tend to be lower-level, nonviolent, and rooted in economic hardship, relational dynamics, or survival. Unlike men, who are more likely to offend in public, women are more likely to commit crimes during the day, in homes or familiar settings, and against people they know.

Women are also more frequently arrested for drug-related offenses, property crimes such as shoplifting or fraud, and offenses tied to poverty or caretaking responsibilities. These acts are often impulsive rather than premeditated and driven by immediate needs such as feeding children, escaping abusive partners, or sustaining addiction. Their involvement in “street economies”—whether through drug sales, theft, or sex work—often reflects a lack of legitimate economic opportunity and inadequate social safety nets.

Two categories stand out where women offend more than men: sex work and embezzlement. Both are offenses that reflect broader gender dynamics. Sex work is often a form of economic survival, especially for women who are homeless, struggling with addiction, or escaping violence. Embezzlement, on the other hand, tends to occur in workplaces where women hold low-level administrative or financial roles—positions that offer opportunity, but little power or pay.

A significant portion of female offending involves male co-offenders, often in the context of intimate relationships. It is not uncommon for women to be pressured, manipulated, or simply drawn into criminal activity by a partner or male peer already engaged in the behavior. This relational dimension complicates perceptions of culpability and challenges traditional justice responses by introducing ambiguity around agency and intent, making it more difficult to assign accountability. Independent violent acts—though still relatively rare—often take place in domestic settings rather than public, and the victims are frequently known to the offender. Mandatory arrest laws in domestic violence cases can also draw women into the system as defendants, blurring the line between victimization and offending.

The rise in female incarceration rates may also be influenced by two intersecting trends: increasing substance use among women and punitive drug policies stemming from the War on Drugs. Approximately one in four women in prison has been convicted of a drug offense. Many women develop substance use disorders as a response to trauma or abuse, and these individuals both progress more quickly from first use to dependency and face higher rates of co-occurring mental health conditions. Yet treatment programs in correctional and community settings are rarely tailored to these realities, leaving many women without effective pathways to recovery. At the same time, sentencing laws, such as mandatory minimum sentences and aggressive enforcement of low-level drug offenses, have increased incarceration, even for nonviolent conduct tied to addiction. This punitive approach has helped drive the surge in drug-related arrests for women, which is outpacing increases among men.

Family, Behavioral Health, and Economic Challenges

Rising incarceration rates do not affect women alone; they reverberate through families, as most incarcerated women are mothers, and many are primary caregivers. Moreover, among those in custody, approximately 5 to 10 percent are pregnant at any given time. In 2023 alone, more than 700 babies were born in custody. This almost always results in the separation of women from newborn children, which disrupts critical developmental bonds made during an infant’s formative years. Distance, cost, and burdensome visitation procedures typically make contact impossible, even when mothers and children want to remain connected. In addition, because women make up a smaller share of the overall prison population, most states operate only one or two women’s facilities—leaving many women incarcerated much farther away from home than male offenders. As a result, more than one-half of incarcerated women never receive a visit from their children, and fewer than one in 10 see them weekly.

When no other family members are available to provide care, children may be placed in the foster care system—a pathway strongly associated with an increased risk of future justice system involvement. Research indicates that foster youth also face higher rates of school instability, mental health challenges, and arrest compared to their peers. The psychological harm of this dynamic extends to mothers as well. Separation from infants deepens their trauma and erodes their mental health resilience. One study found that incarcerated mothers separated from their children experienced three to five times more depression, anxiety, and substance use than other women in jail. Although uncommon, prison nursery programs—where mothers co-reside with their infants during incarceration—offer an alternative approach that supports maternal-infant attachment and has been shown to reduce recidivism.

Economic instability is another factor that fuels and deepens women’s involvement in the justice system. The gender pay gap, higher poverty rates, and lower accumulated wealth make it more difficult for women to afford bail, secure quality legal representation, and pay court fines. These financial constraints increase the likelihood of pretrial detention, which can trigger job loss, eviction, and loss of child custody. Upon release, the barriers intensify. Employers call back 60 percent fewer applicants with criminal records, and women with records get 30 percent fewer callbacks than men with records.

For many incarcerated women, employability is limited not only by past trauma but also by family responsibilities. Gender-responsive employment programs that address women’s specific employment needs strengthen their economic stability after release and reduce their risk of falling back into a financially abusive relationship. Therapeutic communities and peer recovery support are also especially valuable tools for improving outcomes for women after incarceration. If employability issues are left unaddressed during incarceration, they can spiral into post-release homelessness for many women. Those exiting prison are almost 10 times more likely to be homeless than the general public, and women face even higher rates of homelessness than men. Once an individual is homeless, the criminal justice system often becomes a revolving door.

Finally, because today’s justice system was designed primarily around male patterns and circumstances of offending, Congress took steps to ensure that women’s most basic toiletry and dignity needs were met in federal facilities. The First Step Act of 2018 mandated that Bureau of Prisons facilities make tampons and sanitary napkins available to women at no cost. Unfortunately, the operational health of state and local systems varies widely, and many jails at these levels continue to ration feminine supplies or charge commissary fees that create inequities for indigent women. The First Step Act also sought to curb the practice of shackling pregnant incarcerated women. Shackling women during pregnancy has been widely condemned by medical and public health groups. However, it unfortunately continues in some jurisdictions, despite most states having enacted formal bans. Furthermore, fewer than one-half of facilities test women for pregnancy at intake, and many women who test positive receive no prenatal care. Beyond federal legislation, states are also passing legislation—such as the Dignity for Incarcerated Women Act—which would bring reforms similar to the federal First Step Act to state correctional facilities and begin to further right some of these ongoing practices.

Policy Recommendations

Policymakers should pursue reforms that recognize the unique pathways women take into the justice system and the distinct challenges they face once involved. By working to embed gender-responsive practices at key points in the justice process—from arrest and sentencing to custody, reentry, and family reunification—lawmakers can reduce recidivism, strengthen families, and build safer communities. We suggest the following:

• States should develop gender-responsive programs that address how women become involved in the criminal justice system. Research shows that women’s justice involvement is often driven by overlapping challenges such as trauma, economic instability, caregiving responsibilities, and substance use disorders. States should enact gender-responsive, rehabilitation-focused approaches that pair accountability with evidence-based treatment, trauma-informed care, and practical supports like housing, childcare, and employment services.

• Expand gender-responsive specialty courts to address the distinct needs of women and girls in the justice system. Specialty courts have a proven record of reducing recidivism by addressing the root causes of crime through structured, supportive interventions. A Caretaker’s Court would provide a sentencing alternative for sole caretakers, particularly in nonviolent cases, pairing judicial oversight with services that support accountability and family preservation. Similarly, a Girls Court would focus on justice-involved youth, offering gender-responsive support that addresses trauma and social factors contributing to system involvement.

• Correctional facilities should provide free and adequate access to menstrual hygiene products and gender-specific health services for all women in custody. Lack of access to tampons, pads, and menstrual supplies is linked to both physical health risks and psychological harm. In addition to menstrual products, facilities must ensure access to well-woman exams and prenatal care, including screenings for sexually transmitted infections and cervical cancer.

• State and local correctional systems should adopt clear policies for prenatal and postnatal healthcare. Investments in maternal health and early childhood stability reduce long-term justice system and child welfare costs. Policy reforms should guarantee comprehensive prenatal services, ban shackling of pregnant women, and expand access to nursery programs that allow eligible mothers to remain with their newborns during the critical early months of life. Implementing these measures would align correctional practices with health standards, safeguard maternal dignity, and promote healthier child development. Policymakers should pair these reforms with oversight mechanisms to ensure compliance.

• Correctional facilities should adopt gender-specific reentry programs. Reentry programs for women should address parenting demands, deficits in employability, treatment for trauma, and health issues. Implementing risk and need assessments that explicitly consider gender-specific variables can better account for differences that men and women experience upon reentry.

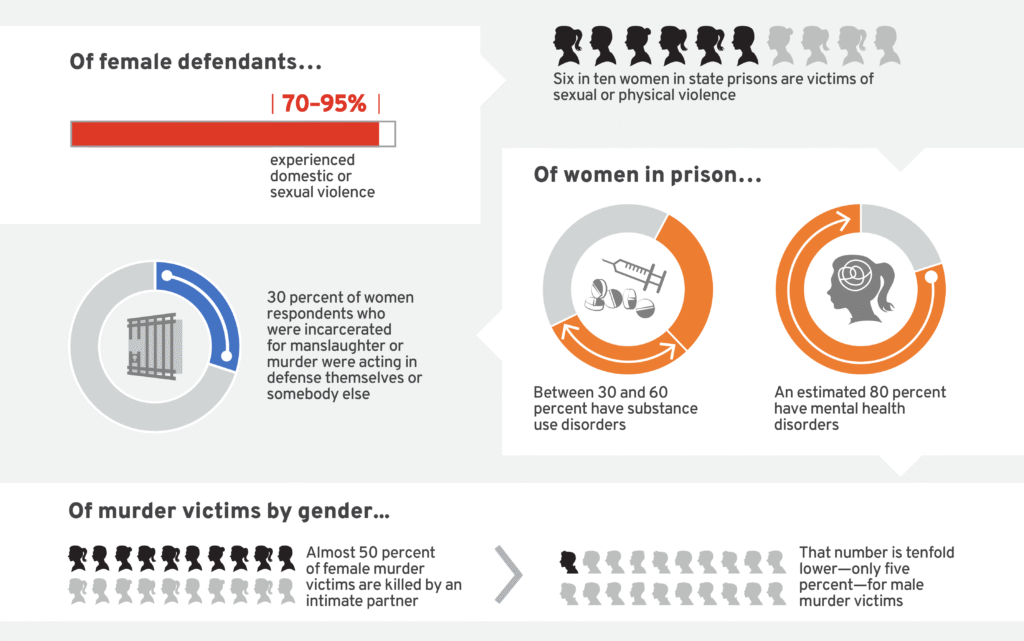

Victims as Defendants

Women in the criminal justice system frequently carry histories of trauma; national data show that one-half of American women experience IPV in their lifetimes. The numbers are even higher for women in the justice system: The National Institute of Justice found that nearly six in 10 women in state prisons have been victims of sexual or physical violence, and other analyses have put this number as high as 86 percent. For many women in custody, criminal behavior cannot be separated from their histories of violence. Any response that ignores this connection risks criminalizing survival rather than addressing the root causes of criminality.

Figure 3: Victims as Defendants

Many women and girls also report polyvictimization, which means experiencing multiple types of victimization, including victimization involving a weapon, sexual victimization, and caregiver perpetration. Polyvictimization in particular can significantly increase the risk of trauma and mental health issues, which frequently result in poor coping abilities and difficulty regulating emotions. Childhood victimization is also common among women who are incarcerated. In fact, more than 90 percent of women in the criminal justice system have either experienced violence themselves or have witnessed extreme violence as children.

The Overlap of Trauma and Criminalization

When left unaddressed, these compounded harms create predictable pathways into the justice system, suggesting that prevention efforts must start with trauma-informed responses in schools, healthcare settings, and policing. Trauma often manifests in ways that can be misinterpreted as defiance, irrationality, or dishonesty—such as difficulty recalling details, heightened fear responses, or seemingly erratic behavior. When those who are in positions to help have an understanding of these dynamics, they are better equipped to interpret behavior accurately, avoid re-traumatization, and respond in ways that foster safety and trust.

One prescient example of victims as defendants in the criminal justice system is sex trafficking, an issue that disproportionately affects women. Some women who are victims of sex trafficking are incarcerated for crimes they were forced to commit while being trafficked. This dynamic highlights how current laws can punish victims of crime rather than their perpetrators, exposing a gap in the justice system’s ability to distinguish between coerced crime and genuine culpability.

Common crimes of this nature include prostitution, theft, fraud, drug offenses, violent crimes, and crimes stemming from self-defense against one’s trafficker. Aside from incarceration resulting from coerced crimes, victims of human trafficking also experience high levels of trauma, which itself can alter judgment, increase risk-taking behaviors, and impair one’s ability to escape abusive situations, leading to a “cycle of criminalization.”

System Policies that Exacerbate Victimization

Statistically, when a woman becomes violent, it is often in self-defense against an intimate partner. Women in these situations are otherwise nonviolent, highlighting that the type of offenses and motivations behind them differ greatly from those of men. Despite this, some studies suggest that women receive longer sentences on average than men for these violent offenses, including for killing their partner. The failure to account for victimization in sentencing can not only deepen inequities between men and women but can also undermine proportionality and fairness.

While many women do indeed perpetrate domestic violence against their partners, when broken down by gender, IPV leads to murder at far higher rates for female victims than for male victims. Almost 50 percent of female murder victims are killed by an intimate partner, whereas this number is 10-fold lower—only five percent—for male murder victims. The higher likelihood for women to be killed by an intimate partner than men can help explain why self-defense against active or threatened violence is a primary motivator for women defendants of violent offenses. In fact, one survey found that at least 30 percent of women respondents who were incarcerated for manslaughter or murder were acting in defense of themselves or somebody else during the commission of the crime. However, most current laws do not take self-defense or current or prior victimization into consideration during the course of prosecution and sentencing.

Of course, not all women in the justice system convicted of violent crimes are there for manslaughter or murder. Although violent offenses perpetrated by women overall have stayed at fairly level rates since the 1960s, one category—assault—has increased. Some believe this may be the byproduct of new “mandatory arrest” laws for domestic violence cases, which result in more prosecutions for lower-level violent offenses like assault.

Mandatory arrest laws were established to address domestic violence. They require law enforcement to make an immediate arrest on the scene if they have probable cause to believe that domestic violence has occurred. As a result, many women—who may in fact be the victims—are arrested either as the sole perpetrator or as part of a dual arrest and are subsequently charged with crimes like assault. This can occur when officers misread signs of self-defense or fail to correctly identify the primary aggressor. Given the gendered nature of IPV, these types of policies disproportionately affect women.

Another issue with mandatory arrest laws is that they deter victims from reporting crimes out of fear that they may be mistakenly viewed as the abuser. Analysis has revealed that the misidentification of victims as perpetrators was already a common problem before mandatory arrest laws and is likely worsened by these laws.

Victims may fear the on-scene arrest of their abusers as well. Even though abuse is harmful to victims, many victims are dependent on their abuser for financial support, childcare, and shelter. They may also fear retaliation—violent or otherwise—from having their abuser arrested, or they themselves may not be prepared for the changes that would come after this irreversible step.

Regardless of whether a woman is arrested and convicted for an abuse-related circumstance, trauma exposure from an abusive environment substantially increases her risk of mental health disorders and substance use. Additionally, abuse is a significant factor in delinquency, addiction, and criminality broadly. Many people turn to drugs or alcohol to cope with abuse, which increases their chances of arrest, particularly for illegal drug use.

The connection between trauma, mental health, and substance use is amplified behind bars, with statistics showing incarcerated women having far higher rates of all three than the general population. Of women in prison, an estimated 80 percent have mental health disorders, and between 30 and 60 percent have substance use disorders. These rates are higher than among men and five times higher than among women in the general population. The care we provide to women with these challenges is insufficient. Suicide remains the leading cause of death in jails, reflecting gaps in screening, monitoring, and treatment. Incarcerated women attempt suicide at higher rates than men, and suicide deaths among female jail inmates have increased by 65 percent over the past two decades.

These behavioral health issues are challenging to navigate outside of a carceral setting, but become even more challenging inside. The carceral environment itself is unsafe for many women. Thousands of allegations of sexual assault are made in correctional facilities every year. Although women are more likely than men to report being sexually victimized by other incarcerated people, correctional staff can be perpetrators as well. From 2019 to 2020 alone, hundreds of staff-on-inmate sexual misconduct cases were substantiated.

After release, the consequences of under-addressed trauma and behavioral health issues intensify. Overdose risk spikes dramatically, with one study finding that overdose is the leading cause of death of formerly incarcerated individuals in the weeks after release, with an especially high risk for women, specifically. This underscores the urgent need for reentry planning that includes continuity of care. Collateral consequences like limited job prospects, minimal savings, housing restrictions, and the potential loss of child custody only add to women’s already precarious situations.

Taken together, these realities show that women’s involvement in the justice system is rarely just about crime itself. It is often the complex product of layered victimization, unmet behavioral health needs, and gendered criminal justice blind spots, all of which demand targeted policy responses geared at slowing the cycle of economic hardship and repeated exposure to victimization and incarceration.

Policy Recommendations

Policymakers must confront the reality that many women enter the justice system not only as defendants, but as prior victims of violence, coercion, and exploitation. Treating these women solely as offenders without accounting for histories of abuse risks criminalizing survival and perpetuating cycles of harm. By adopting policies that recognize trauma, ensure proportionality in sentencing, prevent the punishment of victimization, and stymie further victimization during incarceration, lawmakers can create a justice system that is more equitable, effective, and aligned with public safety. Such policies include the following:

• States should grant sex trafficking victims immunity from prosecution for crimes tied to their exploitation. Victims are often arrested and convicted for crimes such as prostitution, drug possession, or minor theft that occurred under the coercive control of traffickers. States should enact legislation granting immunity from prosecution to victims of sex trafficking for these offenses that are a direct result of their exploitation. Immunity statutes would provide a clear legal safeguard, ensuring that victims are treated first and foremost as victims of crime rather than as offenders. This approach aligns legal practice with the reality of trafficking dynamics, promotes victim recovery, and directs prosecutorial resources toward traffickers and exploiters rather than their victims.

• Key system stakeholders should receive trauma-informed training to improve interactions with victim-defendants. Trauma-informed training for system practitioners—including police, prosecutors, judges, and correctional staff—could improve justice responses and help address the underlying harm that leads many into the system. Making supportive services such as counseling, victim advocacy, and reentry support available throughout the justice system process—including behind bars—can help reduce recidivism and ensure those criminalized due to violent relationships have a safer path to rehabilitation.

• States should pass laws requiring courts to consider evidence of abuse as a defense, mitigating factor, or basis for resentencing. “Survivor Justice Act” laws allow evidence of coercion or trauma to serve as a defense at trial, a mitigating factor at sentencing, and/or a basis for revisiting lengthy terms of incarceration once a victim has demonstrated rehabilitation. This approach ensures that prior abuse is meaningfully factored into the criminal process, recognizing that many victims of domestic violence, sexual assault, or trafficking are criminalized for actions directly connected to their victimization.

• Congress must strengthen the Prison Rape Elimination Act (PREA). The 2003 PREA has fallen dramatically short of its goals. Currently, PREA lacks meaningful oversight or whistleblower protections, which disincentivizes staff from reporting abuse. There is also a conflict-of-interest issue, as audits are performed by former state corrections officials who are paid by the very facilities they are inspecting. Meaningful consequences for states and facilities that repeatedly fail their audits would also help with enforcement. Congress should reform PREA by adding whistleblower protections, requiring independent audits, and imposing meaningful funding consequences for noncompliance.

• States should replace rigid mandatory arrest policies in domestic violence cases with structured discretion. Mandatory arrest laws in domestic violence cases were designed to protect victims, but research and practitioner feedback suggest they can unintentionally undermine safety and discourage victims from calling for help. States should replace rigid mandates with structured discretion, allowing officers to make arrests when evidence clearly supports it, while requiring thorough documentation when alternative interventions are pursued. Coupled with strong officer training, victim-centered safety planning, and access to immediate services, this approach maintains accountability for offenders while reducing the risks of dual arrests, unnecessary detention, and re-traumatization.

Conclusion

For decades, the justice system has failed to recognize how deeply intertwined women’s victimization and criminalization are. A serious response requires more than doubling down on the same practices that do not work for women. It requires policies that account for trauma, economic instability, relational dynamics, health differences, and other factors that drive many women into the system. The rapidly increasing population of women in the criminal justice system has far outpaced research, leaving major gaps in understanding the scope of the problem and studied strategies for addressing their realities. Experts should prioritize updated studies on the factors driving women’s criminality and on effective strategies for rehabilitation and successful reentry after conviction.

Furthermore, policymakers at the federal, state, and local levels must act to build a justice framework that is better at preventing harm, responds to victimization with dignity rather than with skepticism and blame, and encourages accountability without perpetuating never-ending cycles of abuse and incarceration. If we are serious about restoring public trust in the justice system, we must ensure that it fully recognizes women not only as offenders but also as victims whose safety and dignity are essential to the pursuit of justice.