Drug Use 101: What is Overdose?

Author

Media Contact

For general and media inquiries and to book our experts, please contact: pr@rstreet.org

The Definition of Overdose

Most frequently, the word “overdose” is used to describe what happens when a person consumes a larger amount of a substance (usually a drug) than their body can process without causing negative effects. Another way to think about overdose is as severe intoxication. Although not all drug overdoses are fatal, they have caused more than 100,000 deaths annually in the United States in recent years. Overdoses can be either accidental or intentional to self-harm. Currently, the term “overdose” is most often associated with opioids, but overdoses can also occur from prescription medications, illicit drugs, over-the-counter medications, alcohol, caffeine, and even water.

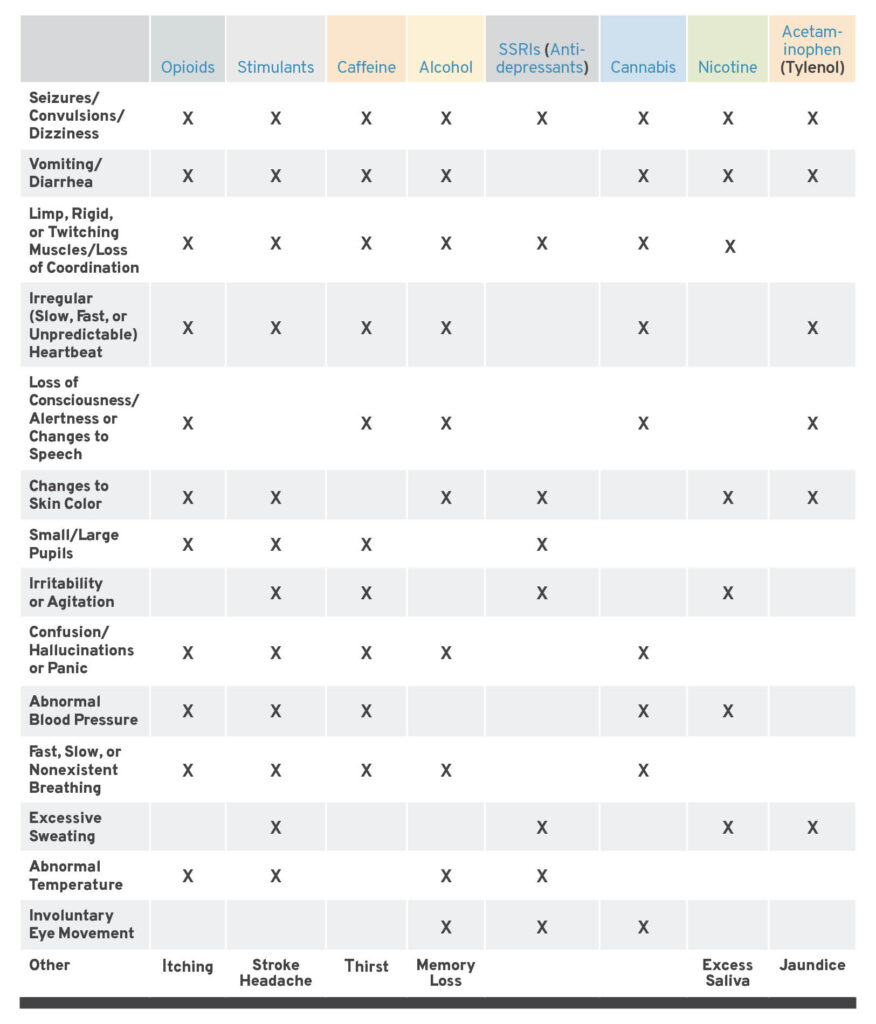

Signs of Overdose by Substance

Different substances cause different symptoms during an overdose. Although not universal, vomiting, seizures or convulsions, irregular heartbeat, and loss of consciousness or alertness are common across overdoses of several different substances.

Policy Can Empower People to Prevent Overdose

While overdose prevention differs depending on the substance used, there are some general precautions that can decrease risk. Using prescription and over-the-counter medication according to the directions provided by the prescribing health care provider or on the packaging are the best ways to prevent overdose. This includes not sharing prescription medications with people for whom they are not prescribed.

For other substances and uses, titrating doses (i.e., slowly increasing the quantity or potency of a substance used) can help achieve the desired effect while decreasing the likelihood of overdose. Starting with the lowest potency is easiest if a substance is regulated and labeled such that consumers can understand its contents. If this information is available, individuals who decide to start using a substance or people returning to use after a period of abstinence should start using the least potent products. Titrating doses can also help prevent unintentional overdose if the substance may contain adulterants (e.g., heroin that may be contaminated with fentanyl).

Another method for decreasing overdose risk is drug checking or testing substances for adulterants. Harm reduction organizations, such as syringe services programs, often distribute fentanyl and xylazine test strips or use more advanced technology to conduct point-of-service checking for multiple substances in a sample of drugs. Laws that limit access to harm reduction programs or criminalize these tools can discourage their use.

Policy Can Improve Overdose Response

Using substances without others present increases the risk of an overdose becoming fatal. Often, emergency services are not the first people on the scene of an overdose. Increasingly, bystanders, many of whom also use drugs, are administering naloxone to reverse opioid overdoses.

Comprehensive naloxone access and Good Samaritan laws (GSLs) are vital to bystander overdose response, as they protect rescuers who provide care or call emergency services from civil and criminal liability. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention suggests that GSLs should provide immunity from arrest, detention, prosecution, parole violations, and warrant searches. Furthermore, comprehensive laws extend these protections to all parties present, not just the person who called emergency services or the person experiencing an overdose. Many states’ GSLs do not include all of these suggested protections.

For opioid overdoses, naloxone access is vital. Although naloxone is now available over the counter, cost and lack of insurance reimbursement or coverage can prevent those most at risk from accessing it. For this reason, programs that distribute naloxone at no cost should be supported by opioid settlement and other public funding mechanisms. And states should retain in perpetuity naloxone access laws that lower barriers to various naloxone formulations, including injectable.

Because drug supply and drug use patterns change, policies must be flexible to allow organizations serving people who use drugs to adapt in real time according to local needs.