Applying Behavior Change Theory to Policy Can Help Older Americans Who Smoke

Author

Table of Contents

- Encouraging Quitting by Shifting Perceptions

- Supporting Quit Attempts Among Older Smokers

- Applying Theory to Policy

Media Contact

For general and media inquiries and to book our experts, please contact: pr@rstreet.org

Smoking cessation is a case in which the saying “If at first you don’t succeed, try, try again” is particularly relevant. It typically takes many attempts to achieve long-term success; in fact, estimates range from an average of six to 142.

Trying to quit is vital to quitting successfully, and older people—the group that accounts for more than 70 percent of smoking-related deaths annually—are less likely to attempt to quit than younger people. This contributes to the persistently slow decline in smoking rates among people over 65. Deciding to quit smoking is a personal decision that depends on many factors, but appropriate policies can help shift the scales toward quitting.

Encouraging Quitting by Shifting Perceptions

Applying behavior change theories to targeted policies and interventions can help inspire older smokers to quit. First, acknowledging that the decision to quit smoking involves multiple stages of thought, recognition, and decision-making can help policymakers understand there is no “one-size-fits-all” approach to encouraging smoking cessation. Different types of programs are required to fulfill different needs within this group.

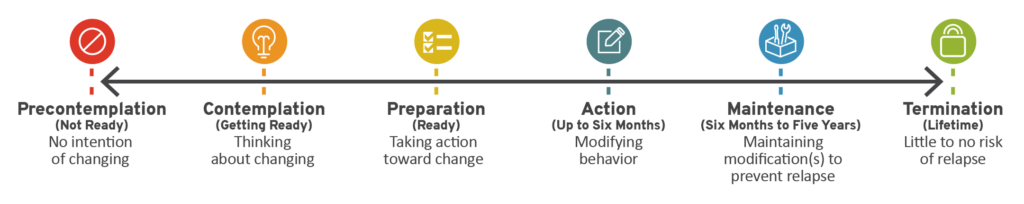

The transtheoretical model of change (TTM) outlines six phases of behavior change:

Each stage necessitates different approaches to help people progress. For example, educational campaigns might be especially effective at helping people move from Precontemplation to Contemplation while quitlines and other support programs might be more effective for people in the Preparation, Action, or Maintenance phases.

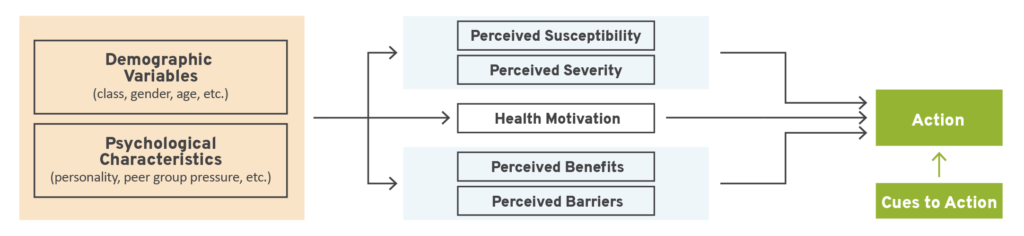

The health belief model (HBM) can help further refine which tools and messages smoking cessation policies should support by explaining how people’s beliefs and assessments of personal circumstances influence their actions. This model posits that individual motivation and perceptions of benefits, barriers, risks, and potential outcomes dictate action. It allows policymakers to focus on tools that can help shift perceptions and spur action among older adults who smoke.

Using the HBM to understand how perceptions and motivation might differ at each stage in the TTM can help focus and tailor policies for maximum effectiveness. Together, these models offer a powerful framework for building policies that promote change.

Supporting Quit Attempts Among Older Smokers

Although individuals are ultimately responsible for deciding to change their behavior, policies can provide motivation through external cues and support. The government supports several programs to help people quit smoking, including online resources and quitlines that provide support over the phone. However, older smokers are less aware of these resources and use them less frequently than younger smokers. Developing tailored and targeted campaigns to increase awareness of existing resources among older smokers can help modify their health beliefs, moving them toward taking action to quit. Similarly, these campaigns can provide information that helps older smokers move through the early stages of the TTM toward actively quitting.

Believing that change is possible is also important to quitting smoking, and older smokers can have lower self-efficacy in this area than younger smokers. When considering which cessation programs to expand and support, their effect on self-efficacy is a critical measure. Programs that include social support and/or cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) are shown to increase self-efficacy around smoking cessation. Social support is important throughout the stages of change, and CBT can give older smokers the tools to decrease perceived barriers to quitting, change their health beliefs, and motivate action.

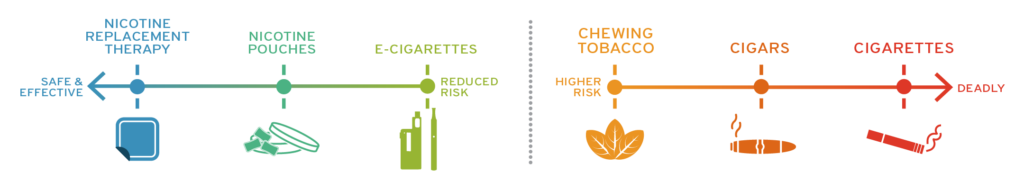

For some older smokers, quitting smoking may not mean quitting nicotine completely. Smoking is the most harmful way for a person to consume nicotine, which is the chemical that makes cigarettes addictive. Switching to an alternative nicotine delivery system (ANDS) like e-cigarettes or nicotine pouches decreases exposure to many of the harmful chemicals in cigarette smoke and can lead to complete smoking cessation. Switching from smoking to a reduced-risk ANDS product can help a person in the Action and Maintenance phases of the TTM; however, older smokers use ANDS at the lowest rates, and many misperceive their risk relative to cigarettes. Meanwhile, the HBM can help policymakers understand these misperceptions in order to create tailored health campaigns that encourage switching.

Applying Theory to Policy

As policymakers determine which programs and policies can have the greatest impact on smoking cessation rates among older adults, the HBM and TTM can be useful—the HBM describes why older smokers continue to smoke, while the TTM defines the behavioral phases of change. Health beliefs and appropriate interventions will differ at each phase, providing many avenues for reaching older smokers through policy. Theory-driven policies targeted and tailored toward this hard-to-influence population will be most beneficial.

Continuum of Risk*

The continuum of risk shows that not all tobacco or nicotine products are equally harmful. They range from nicotine replacement therapies, designed to assist individuals in moving away from smoking, to combustible cigarettes, the highest risk category on the spectrum.

* The placement of products in this graphic is intended to illustrate general categories of risk associated with each product. It is not to scale and should not be interpreted as a precise comparison of products, as comprehensive data to determine exact relative risk is not available.