Abused by the State: The Hidden Crisis Inside America’s Juvenile Detention System

Author

Table of Contents

- Executive Summary

- Introduction

- Sexual Abuse in Juvenile Detention

- Failure of the Prison Rape Elimination Act

- Delayed Justice and the Legal Reckoning

- Financial Fallout

- The Staffing Crisis

- “Zero-Tolerance” Recommendations

- Conclusion

Media Contact

For general and media inquiries and to book our experts, please contact: pr@rstreet.org

A zero-tolerance approach requires that juvenile justice policies mitigate abuse, hold abusers accountable, and demand responsibility from leadership.

Executive Summary

On any given day, about 27,000 children and teens are held in juvenile detention centers across the United States. Despite decades of reform, these facilities continue to be plagued by reports of sexual abuse. This trauma, particularly when inflicted by those in positions of authority, compounds the baseline harm that comes with youth incarceration.

This policy paper explores systemic sexual abuse in America’s juvenile detention system and discusses new developments suggesting that it is more pervasive than previously believed. Specifically, recent changes in the law have allowed thousands of former detainees to come forward with credible allegations of staff misconduct, triggering a wave of litigation and multibillion-dollar settlements that threaten to overwhelm public budgets.

Drawing on these legal developments, recent data, and concerning reports, we find that juvenile detention facilities have failed to uphold their dual mandate of rehabilitation and public safety. In fact, many facilities have become threats in and of themselves, perpetuating cycles of abuse and criminality among already vulnerable youth. The persistence of abuse in state-run youth facilities undermines both the rehabilitative mission of juvenile justice and the public’s trust in government. It also creates long-term public safety concerns by perpetuating cycles of trauma, recidivism, and system involvement.

To address these failures, we offer an evidence-based policy roadmap to strengthen the Prison Rape Elimination Act, expand reporting mechanisms, raise hiring standards, update infrastructure, and bolster oversight. These recommendations should be combined with a strategic reduction in the footprint of secure detention overall, as the most effective safeguard against institutional abuse is to reduce unnecessary incarceration in the first place.

Introduction

Over the past 25 years, youth incarceration in the United States has declined sharply, driven by falling crime rates and a growing preference for diversion and rehabilitation over detention. Since its peak in 2000, the number of young people held in U.S. detention facilities has dropped by 77 percent.

Intuitively, one might expect that as detention rates fall, conditions inside would improve. Yet reports of abuse within these facilities are more frequent than ever. Recent high-profile investigations have chronicled everything from “gladiator fights” between detained youth to chronic sexual abuse involving thousands of victims in dozens of states. Changes in state laws—particularly those extending or eliminating statutes of limitations on child sexual abuse reporting—have exposed a scale of institutional abuse so widespread that it invites comparison to the Catholic Church crisis. The systems intended to rehabilitate have become a clear and present danger to the very youth they were meant to serve.

While there is a legitimate public safety interest in detaining certain individuals—sometimes even young people—there is also a public safety interest in ensuring that children are not unnecessarily incarcerated, subjected to psychological harm, or sexually assaulted while under state supervision. If the phrase “law and order” is to have any meaning, it must begin inside our criminal justice institutions. This paper traces the scope and nature of sexual abuse in juvenile detention, documents the institutional failures behind it, and proposes a series of evidence-based reforms to establish a true zero-tolerance system.

Sexual Abuse in Juvenile Detention

Sexual abuse in juvenile detention remains disturbingly pervasive, despite federal efforts to prevent it. The Bureau of Justice Statistics’ (BJS’) most recent survey on the issue (conducted in 2018) found that 7.1 percent of detained youth reported sexual victimization during their time in custody—a rate significantly higher than that seen in adult prisons. Understanding why sexual abuse persists in juvenile justice systems requires a closer look at the conditions and oversight failures that sustain this pattern of harm.

Youth in custody are acutely vulnerable to abuse. Separated from their families, they are placed under the authority of institutional staff who oversee their daily lives. This power imbalance is magnified by the fact that adolescents are neurologically immature, with underdeveloped executive functioning, weaker impulse control, and a limited ability to navigate coercive situations. This vulnerability is heightened by children’s natural deference to authority and desire for approval, making them uniquely susceptible to institutional abuse.

Youth in the justice system are also more likely to be struggling with trauma, mental illness, or substance use, which can be used as levers for exploitation and manipulation. Investigative reporting and court documents filed in connection with recent lawsuits detail accounts of juvenile detention staff allegedly “grooming” victims with offers of drugs and special privileges or threatening youth with extreme punishments like solitary confinement to prevent abuse reporting.

Analyses of the BJS survey suggest that most cases of abuse occur in crowded, understaffed, state-run facilities and draw attention to some noteworthy differences between the victimization of male and female youth. For example, although a higher percentage of male than female youth (6.1 percent vs. 2.9 percent) reported sexual abuse by a staff member, a higher percentage of female youth (4.7 percent vs. 1.6 percent) reported sexual abuse by other youth. In addition, although most sexual violence in society is committed by men, in juvenile detention, the majority of serious incidents of staff-on-youth sexual misconduct involve female staff alone (91 percent). Dishearteningly, authorities often dismiss or discredit allegations of sexual abuse that come from incarcerated youth; fewer than one out of every 10 claims are verified, and perpetrators rarely face criminal charges.

Failure of the Prison Rape Elimination Act

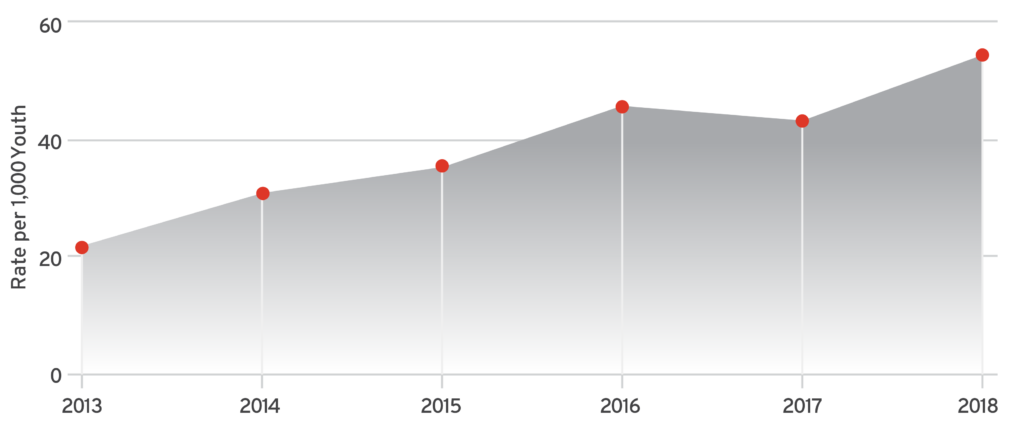

The continued failure to protect children in residential detention raises urgent questions about federal and state oversight. In 2003, Congress passed the Prison Rape Elimination Act (PREA) to prevent sexual abuse in U.S. correctional institutions. Ten years later, the U.S. DOJ released the final PREA standards for juvenile facilities, which limited isolation, prohibited cross-gender pat-downs, and required staff-to-youth ratios of 1:8 during waking hours. Still, PREA has failed to reduce sexual abuse in juvenile facilities. On the contrary, since the standards went into effect, reports of sexual victimization in juvenile detention facilities have increased by 89 percent, and the rate of juvenile sexual assault has more than doubled, from 21.7 incidents per 1,000 youth in 2013 to 54.1 per 1,000 in 2018 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Rate of Sexual Abuse Allegations per 1,000 Youth, 2013 to 2018

The spike in juvenile sexual assault is likely not the result of enhanced reporting. PREA lacks meaningful oversight or whistleblower protections, providing little incentive for correctional staff to report abuses—especially when doing so risks retaliation. Although PREA does outline statutory protections against retaliation, they are not enforced, leaving staff and youth vulnerable to reprisals. Thus, because the law lacks external enforcement mechanisms or whistleblower protection infrastructure, compliance varies widely across states.

Delayed Justice and the Legal Reckoning

Importantly, official BJS statistics represent only a fraction of the abuse that has occurred (and continues to occur) in juvenile facilities. Many survivors are just now coming forward with accounts that date back decades, long after their time in custody. The true extent of misconduct in juvenile facilities will likely never be known. Most victims of childhood sexual abuse (CSA) delay disclosure for decades; studies show that between 55 and 70 percent of CSA survivors wait until adulthood to disclose abuse, typically between the ages of 40 and 50. Moreover, when a perpetrator holds a position of authority—such as a clergy member, educator, or correctional officer—victims may be more reluctant to come forward. In more than one-third of cases, abuse is never reported to authorities.

Legal and institutional barriers further complicate reporting. Statutes of limitations are the legally defined timeframes within which a victim must file civil or criminal charges. These deadlines vary widely by state and by criminal offense, but in many jurisdictions, CSA survivors have as little as five years after reaching adulthood to take legal action. This is long before most are emotionally prepared to come forward or old enough to fully articulate what happened to them. In Michigan, for example, attorneys representing a dozen plaintiffs in a recent case estimated that 20 to 30 times more victims were affected but barred from suing because of the statute of limitations.

Statutes of limitations in sexual abuse cases have drawn increased scrutiny in recent years. The #MeToo movement, which began in 2017, prompted a wave of state legislation extending—or even eliminating—statutes of limitations on certain sex crimes. So far, 44 states have eliminated such statutes for at least some CSA-related felonies, and 19 states have removed them for civil suits altogether. In addition, in 2022, Congress removed the time limit on civil claims in federal court. Beyond these efforts, 30 states have passed so-called “revival” or “lookback” laws, which allow survivors to file previously expired civil claims. These laws generally come in one of two forms: revival windows, which establish a set period during which survivors can file old claims, and revival age, which allow victims to sue until a designated age, usually between 27 and 55 years.

In 2025 alone, lawmakers in 18 states introduced bills aimed at giving CSA survivors more time to seek justice. Although these measures provide survivors with an opportunity for closure, their value extends beyond those who were personally affected by the abuse, helping to identify serial abusers and problem institutions and making the entire system safer.

Financial Fallout

For decades, sexual abuse in the juvenile detention system was hidden behind walls of silence. Survivors were ignored, discredited, or barred from compensation because of restrictive statutes of limitations. As a result, the public had little sense of the scale of abuse occurring inside these facilities. Opening the legal floodgates has allowed thousands of former juvenile detainees to come forward for the first time, revealing deeply entrenched patterns of exploitation, complacency, and institutional cover-up (Table 1). The harrowing accounts—from illegal strip searches to violent rapes—date back to the 1980s and earlier. As a result, jurisdictions are now facing massive legal exposure, and settlement costs are straining public budgets. To manage these costs, state governments have had to issue bonds, delay infrastructure projects, and cap legal liability. For example:

• New Hampshire removed the statute of limitations on CSA in 2020, shedding light on over 1,300 previously unknown incidents of correctional abuse. In one case, the jury awarded $38 million to a man who alleged he was repeatedly raped, beaten, and held in isolation as a teenager. If even half of the state’s pending lawsuits result in comparable awards, the total cost to the state could reach $25 billion—$10 billion more than its entire biennium budget.

• Maryland passed the Child Victims Act in 2023, removing the statute of limitations and allowing victims to receive up to $890,000 in compensation per abuse incident. Since then, 3,500 victims have filed claims, with thousands more anticipated. Overwhelmed by the volume, the Maryland Attorney General’s Office issued a call for attorneys specializing in child abuse cases. When the state’s financial exposure became unsustainable, lawmakers were forced to cap damages and clarify the scope of abuse claims.

• California extended the deadline for filing civil CSA claims to age 40 and introduced a three-year “lookback window” for older cases. The response was overwhelming. In April 2025, Los Angeles County tentatively agreed to a $4 billion settlement covering more than 6,800 sexual abuse claims dating back to 1959. If approved, it would be the costliest municipal settlement in history, requiring annual payments in the hundreds of millions through the 2050s. A recent county budget document described the payouts as the “most serious fiscal challenge in recent history.”

Table 1: Sampling of Juvenile Detention Sex Abuse Lawsuits

| State | No. of Reported Abuse Lawsuits* | Recent News Article/Documentation |

| Arkansas | 9 | CBS 4 Local News |

| California (LA County) | 6,800 | Courthouse News Service |

| Illinois | 800+ | CBS News Chicago |

| New Hampshire | 1,300+ | The Press Democrat |

| New Jersey | 108 | New Jersey Courts |

| New York (NYC) | 539 | New York Post |

| Louisiana | “Dozens” | The New York Times |

| Maryland | 3,500+ | Stateline |

| Michigan | 35 | Click On Detroit |

| Oklahoma | 20 | Oklahoma Appleseed |

| Oregon | 26 | KGW 8 |

| Pennsylvania | 200+ | WHYY |

| Texas | 100+ | U.S. DOJ |

| Washington | 36 | The Stranger |

The Staffing Crisis

The current wave of scandals plaguing America’s juvenile detention centers comes at a paradoxical moment: Although fewer youth are in custody than ever before, reports of abuse are rising. One explanation for this is the ongoing recruitment and retention crisis affecting juvenile justice facilities nationwide. Nearly 90 percent of state-run systems report moderate to severe staffing shortages with vacancy rates reaching 30 to 40 percent in some jurisdictions. This is partly because of lower pay rates among juvenile detention workers who earn, on average, 33 percent less than other kinds of law enforcement workers.

To cope with these staffing shortfalls, juvenile systems have lowered hiring standards to remain in operation, leading to a decline in both the quality and quantity of available personnel. Many youth entering detention have mental illnesses, substance abuse issues, and traumatic pasts. To effectively rehabilitate youth facing these challenges, correctional staff should be trained in cognitive-behavioral therapy, trauma-informed care, and substance abuse counseling. Yet juvenile facilities are struggling to recruit professionals with these skill sets. Additionally, a strong labor market has allowed mental health professionals to find safer, better-paying jobs in other sectors. To remain open, facilities are hiring individuals who lack the qualifications and temperament needed to adequately address these youth’s specialized needs.

Staffing shortages not only weaken rehabilitation efforts but also compromise basic safety. Under PREA, secure juvenile facilities must maintain minimum staffing ratios to ensure adequate supervision and reduce opportunities for misconduct. In recent years, dangerously low staffing levels have forced juvenile detention centers to implement “operational confinement” on days when facilities are short-staffed. Confined to cells for multiple days at a time, children in one Texas facility resorted to using water bottles and lunch trays as toilets because staffing levels were insufficient to allow for trips to the bathroom. Last year, citing a lack of adequate supervision as a major contributor to the abuse problem, the DOJ warned Texas that it would face federal litigation under the Civil Rights of Institutionalized Persons Act if it did not improve conditions, admonishing the state for “failing to prevent staff from sexually abusing children.”

The Dangers of Understaffing

When correctional officers leave their jobs, a primary reason they cite is working conditions, which have deteriorated dramatically across the country. This has led to preventable tragedies. In November 2022, a teen at an understaffed Kentucky detention center assaulted a staff member, stole their keys, and released other youth from their cells. During the ensuing riot—which staff described as “pure chaos”—a teenage girl was sexually assaulted, a 13-year-old male detainee was severely beaten, and an injured worker had to be evacuated via helicopter. Order was restored only after armed state troopers and other law enforcement officers donned riot gear to retake the facility. The incident sparked a DOJ inquiry and raised questions about the safety of similarly understaffed facilities in other states.

“Zero-Tolerance” Recommendations

The most effective way to prevent abuse in juvenile detention facilities is to reduce the number of youth in secure detention. This approach is both a moral and a practical imperative that not only minimizes the risk of institutional abuse but also improves long-term outcomes. States like Florida have achieved significant public safety gains while simultaneously reducing juvenile confinement, eliminating thousands of residential beds by using civil citation-based deflection programs to keep youth out of the system. Such steps are critical, as each youth kept out of the system is one less child vulnerable to harm behind bars.

For youth who do require secure placement, strong oversight, improved staffing, and meaningful accountability are vital. The following 10 evidence-based, actionable solutions form a blueprint for a zero-tolerance approach to sexual abuse that will make facilities safer for youth and staff alike.

1. Tie PREA Compliance to Meaningful Consequences. Increase financial penalties for noncompliance beyond the current 5 percent cap on DOJ grant funding—a minimal cost compared to the expense of addressing the issue. States and facilities that repeatedly fail PREA audits should lose eligibility for federal juvenile justice funds until they improve.

2. End Conflict-of-Interest Auditing. PREA audits are performed once every three years by former state corrections officials known as “certified auditors.” This is problematic because they are paid by the very facilities they are inspecting, and private or contract facilities like immigrant detention centers often go overlooked. Lawmakers should establish independent Inspectors General or Ombudsmen to conduct regular, unannounced inspections of youth facilities, review complaints, and report publicly on conditions.

3. Incentivize Reporting. Too often, reports of sexual abuse must go through internal channels, meaning victims and workers must report abuse to the very institution where it occurred. Whistleblower protections should shield staff who speak out, and youth should have accessible, safe channels—like an abuse hotline or dedicated child advocate—for reporting mistreatment without fear of retaliation.

4. File Criminal Charges. Abuse must be met with swift and certain consequences, and perpetrators must be prosecuted. PREA sets institutional standards but provides no mechanism for external investigation by law enforcement or criminal prosecution. Additionally, administrators who knew of abuse and did nothing to stop it should also be subject to charges.

5. Update Technology. Video monitoring deters abuse, provides evidence, and protects youth and staff from false allegations; however, these systems are notably outdated. Congress recently required federal prisons to upgrade cameras and should provide grants for juvenile facilities to do the same. Additionally, juvenile systems should consider implementing body cameras when staff interact with youth.

6. Raise Hiring Standards. Juvenile detention facilities should be staffed by professionals trained to meet the complex needs of at-risk youth. States should increase funding to recruit and retain staff with relevant clinical expertise, including adolescent psychology, de-escalation techniques, and crisis intervention. Without competitive pay and professional development pathways, juvenile systems will continue to rely on underqualified workers, undermining rehabilitation and placing youth at risk.

7. Fund Juvenile Justice. Youth thrive when they can develop connections and follow a consistent routine, but high staff turnover disrupts continuity of supervision and relationship-building between youth and staff. Jurisdictions can improve recruitment and retention by offering competitive salaries and benefits, closer to what law enforcement officers earn. More staff on duty would also mean better supervision and more opportunities for constructive programming, giving bad actors fewer places to hide.

8. Downsize Detention. Large, warehouse-like institutions should be phased out in favor of smaller, community-based settings. Research shows that smaller facilities grouped by risk level and therapeutic needs have better outcomes and lower abuse rates. Shifting the institutional culture from a correctional mindset to a therapeutic one would help minimize the power differential that leads to abuses of authority.

9. Develop an Abuse Mitigation Plan. Facilities must develop a comprehensive plan that goes beyond PREA requirements. The plan should consider multiple factors, including physical layout, resident demographics, prevalence of abuse, programmatic needs, and the use of monitoring technology.

10. Full Transparency. Although PREA requires states to report data to the BJS, the level of public disclosure varies drastically by state. Some states, like Louisiana, Texas, and Pennsylvania, voluntarily release disaggregated data, including numbers broken down by facility, substantiated vs. unsubstantiated cases, and multi-year trend analyses. More jurisdictions should create a culture of transparency so policymakers and the public can make informed decisions.

Conclusion

For years, certain juvenile justice systems have downplayed the problem of CSA within their walls. Today, with thousands of survivors now coming forward and filing lawsuits, it is no longer possible to deny the problem. Civil litigation has forced long-overdue public reckonings, but the issue is ongoing, and justice can no longer wait until a tragedy occurs. A zero-tolerance approach requires that juvenile justice policies mitigate abuse, hold abusers accountable, and demand responsibility from leadership. Policymakers must work to eliminate the conditions that allow CSA to occur, such as understaffing, secrecy, and institutional inertia. But—more than that—they must also prevent unnecessary detention in the first place. Every child who is supervised in the community is one less child vulnerable behind bars. If we are serious about ending the CSA epidemic in juvenile facilities, we must move beyond damage control and dismantle the structures that perpetuate harm.

This research was funded by the Annie E. Casey Foundation, and we thank them for their support; however, the findings and conclusions presented in this report are those of the author(s) alone, and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the Foundation.