Testimony for Fostering A Healthier Internet to Protect Consumers Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act

SUBMITTED STATEMENT FOR THE RECORD OF

JEFFREY WESTLING

FELLOW, TECHNOLOGY AND INNOVATION

R STREET INSTITUTE

KRISTEN NYMAN

GOVERNMENT AFFAIRS SPECIALIST, TECHNOLOGY AND INNOVATION

R STREET INSTITUTE

SHOSHANA WEISSMANN

FELLOW & SENIOR MANAGER FOR DIGITAL MEDIA

R STREET INSTITUTE

BEFORE THE

HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES COMMUNICATIONS AND TECHNOLOGY AND

CONSUMER PROTECTION AND COMMERCE SUBCOMMITTEES

OF THE

ENERGY AND COMMERCE COMMITTEE

HEARING ON

FOSTERING A HEALTHIER INTERNET TO PROTECT CONSUMERS

SECTION 230 OF THE COMMUNICATIONS DECENCY ACT

OCTOBER 16, 2019

CHAIRMAN DOYLE, CHAIRWOMAN SCHAKOWSKY, RANKING MEMBERS LATTA AND MCMORRIS RODGERS, AND MEMBERS OF THE COMMITTEE:

Thank you for holding this important hearing on fostering a healthier Internet to protect consumers and Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act. This statement is offered by scholars at the R Street Institute who have studied Section 230 extensively.[1]

A hearing about Section 230 is necessarily a hearing about speech on the Internet. That topic is critical as the Supreme Court recognized in Reno v. ACLU, when it described the free speech capacity of “the vast democratic forums of the Internet.”[2] But it is often difficult to perceive that capacity in the abstract.

So in an effort to make it more concrete, this testimony focuses on one idiosyncratic form of online speech, one that has taken the Internet and the culture at large by storm over a very short number of years, one that is immediately recognizable to all, one that is chided by some yet loved by many, one used by those of all walks of life from the high school freshman to the United States Government: the Internet meme.[3]

The Speech Value of Internet Memes

While the term “meme” can refer to a wide variety of concepts, the most colloquially understood form of meme is the image-based visual meme. These memes have grown tremendously popular because of their relative simplicity, allowing users to take an existing idea and morph it to convey a new one.[4] Social media also allows memes to spread at breakneck speeds to people across the world, further increasing their popularity as more individuals see and share them.[5] As they spread, memes can become an entire body of communication among individual users who contribute new variations upon a meme that continues to change as the image spreads.[6]

To understand how this works in practice, consider the meme known as the “socially awkward penguin.” The base format is simply a penguin on a blue background, with captions above and below—but on that canvas users can relay embarrassing stories from their lives.[7] While humorous, these images also are a way of letting out frustration and gaining a sympathetic ear from strangers across the world.

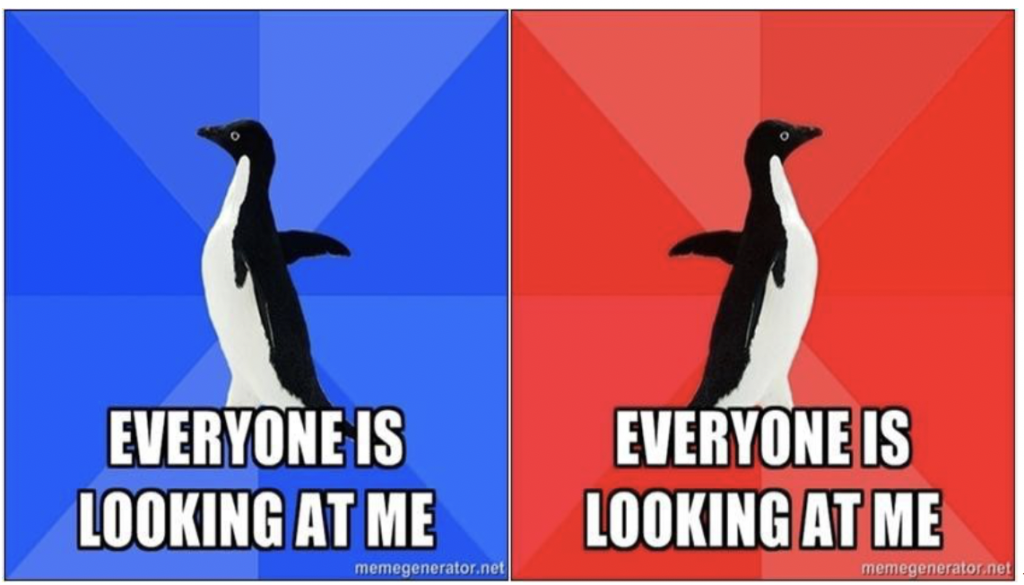

As a meme format becomes more popular, it evolves and mutates to convey new ideas. The “socially awkward penguin,” with only an image flip and a background color change, became the “socially awesome penguin,” allowing users to share life’s little victories.[9] Consider the two memes below, which to a layperson appear nearly identical, but to those knowing that the blue image indicated awkwardness and the red confidence, understand them to be completely different.

The last major evolution of the meme came with a combination of the two, allowing the creator to tell stories of turning a socially awkward situation into a socially awesome one. Juxtaposing the two penguin memes above, as one insightful Internet denizen did, tells a remarkable story of self-esteem and personal gumption, entirely through a shared understanding of a seemingly meaningless graphic.[11]

Clearly, memes are not mere images; they are a method of communication. They allow individuals to condense complex topics into simple formats and share these thoughts with others across the globe. More importantly, they create connections between these individuals and form communities that otherwise would be drowned out by larger interests. As Harvard professor Jonathan Zittrain explained, “A meme at its best exposes a truth about something, and in its versatility allows that truth to be captured and applied in new situations. So far, the most successful memes have been deployed by people without a megaphone against institutions that often dominate mainstream culture.”[12]

This innovative mode of communication can lead to both significant benefits and potential harms for users online. In a survey study on the impact of social media among teenagers, a Harvard Graduate School of Education researcher found that the vast majority felt empowered sharing their identity through social media.[13] Those surveyed indicated that they utilize various platforms for self-expression, personal development and growth, relational interactions and exploration.[14] And while a spectrum of positive and negative feelings were experienced, the positive reactions tended to outweigh the negative.[15] The study thus simultaneously confirms the communicative power that social media platforms can have and highlights the potential harms of social media, noting the presence of harmful content as a particularly difficult challenge.[16]

Memes also serve as visual tools used to critique expression, movements and popular online culture.[17] A 2014 study looked at popular usage of “emoticons,” the small graphics used in short messaging services to convey anything from smiles to sadness (essentially a small-format meme).[18] Among the reasons for emoticon use were to “[i]mprove understanding of message (35 percent), [c]reate a better atmosphere (22.5 percent), and [shorten time spent] writing (18.8 percent).”[19] These results strengthen the value of image-based communications and memes as an effective tool for communication.

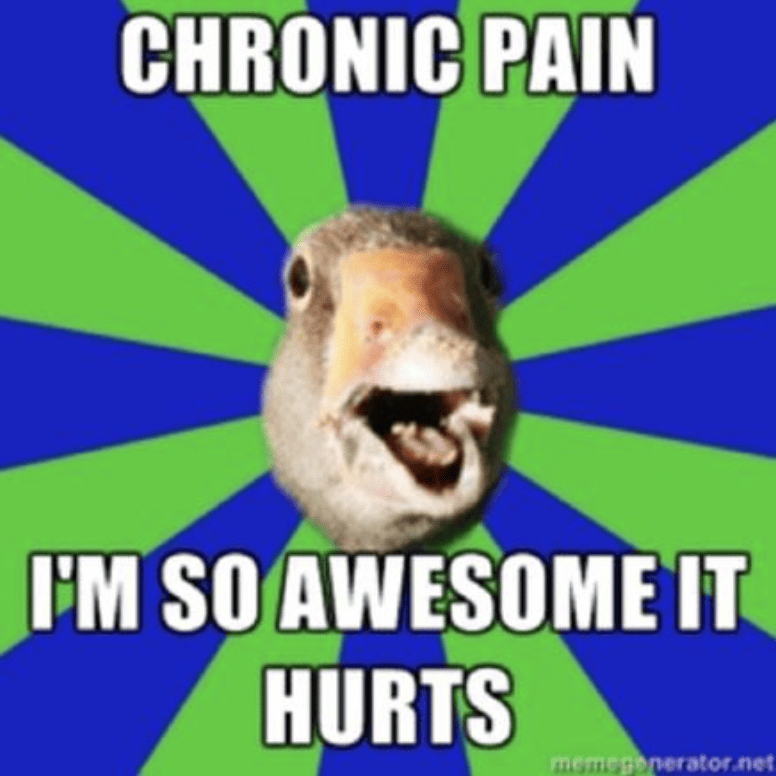

It is not hard to find anecdotes about the communicative potential of memes. Individuals with chronic pain often face skepticism and misunderstanding from those who have no frame of reference for the issue. Unfortunately, for many of these people, finding some form of community or understanding can be challenging.[20] Memes present an opportunity for this community, allowing bloggers and users to share their daily challenges and create a place where others will listen and comfort. One such community, for example, has adopted the “fibromyalgia duck” as a mascot in a campaign of memes—originating offline in fact, from a fundraiser involving actual rubber ducks[21]—helping to facilitate connection with each other and express to the world the nature of their condition.[22]

As with the chronic pain community, memes present an opportunity for distinct but disparate communities that would be unlikely to form without the immense size of social networks. People searching for these communities can find a home in these online spaces, as one social anthropologist writes: “By their admission, many seek and find ‘a family,’ a place where others will listen, somewhere one can turn to even when other social worlds might be unavailable due to the often random, persistent, and unpredictable temporalities of pain.”[24]

And this community feeling is not limited to medical problems: Communities are built around memes relating to a variety of topics such as specific gender identities, which have grown immensely on sites like Reddit.[25]

Memes can also convey public service information. In Utah, researchers developed an online campaign utilizing memes to promote healthy family meals.[26] With cuts to funding, researchers asked whether using memes and engaging with communities online presented an opportunity to reach these audiences.[27] While not definitive, the results of the project indicate the potential efficacy of such an approach.[28]

In the field of policy, memes are a crucial form of advocacy, connecting with supporters, engaging bipartisanship and achieving policy goals. Indeed, our organization, the R Street Institute, frequently uses memes to amplify its perspectives and resonate with an ever-increasing online audience. Congressman Tim Ryan retweeted an R Street GIF supporting our stance on Congressional Research Service reform.[29] In this instance, the video meme connected a right-of- center think tank and a Democratic congressman on a policy issue.[30]

Similarly, Senator Marco Rubio responded to an R Street tweet about lowering regulatory barriers for employees; dozens of others from varying political backgrounds commended him for it.[31] Memes, in these instances, were effective in not only communicating a desired message clearly, but also in connecting opposed political groups.

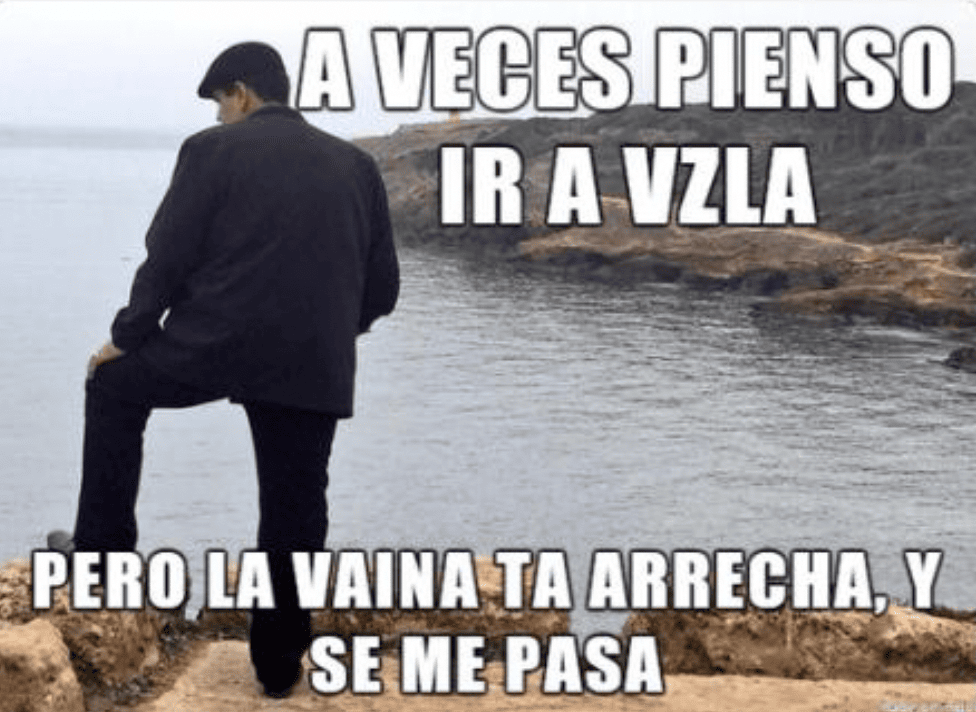

Perhaps more importantly, in countries without strong democratic processes, memes have served as a tool to express dissent, akin to a public protest.[32] Venezuela, for example, has restricted Internet access, removed content and blocked websites that promote criticism of the Maduro regime.[33] In order to subvert their attempts to remove protest content, many political dissidents have used memes, which are not as easily indexed by search algorithms (because they are images), to make it more difficult for the government to find and remove content.

Consider the following meme, which originated as a government photo to promote Maduro but ended as a vehicle for political criticism, with the added caption imagining Maduro pondering, “Sometimes I think of returning to Venezuela / But then I remember how bad the situation is, and the feeling passes.”[34]

To be sure, malicious actors can exploit this increased communicative power and virality of information to cause harm. Especially in the current era of disinformation, where individuals tend to trust and believe information that confirms preexisting beliefs and worldviews,[36] this predisposition to confirmation bias means that complexities are often lost in the wind. The emotional connections memes create between uncommon viewpoints can help underserved communities, but they can also enable tactics of persuasion that discard truth and nuance in favor of discord and faction. The simplicity of image-based memes, therefore, presents a unique opportunity for malicious actors to spread disinformation or hateful content online to individuals who will see the information, like it and continue its propagation.[37] The Internet Research Agency, for example, used memes as a way of dividing Americans during the runup to the 2016 elections.[38]

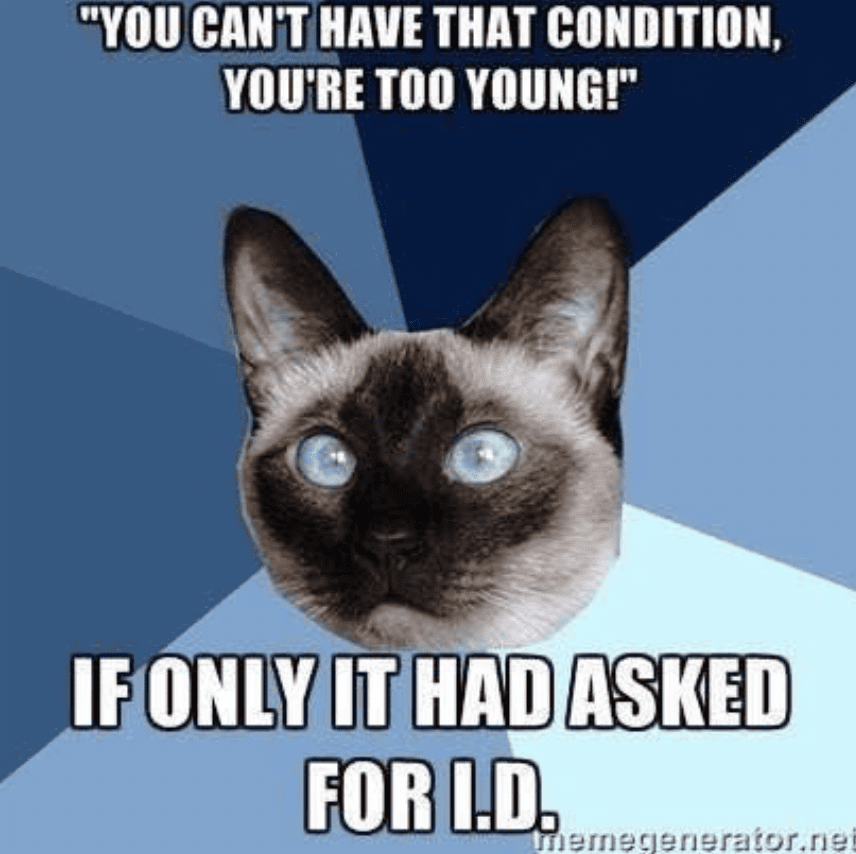

What this potential harm highlights, however, is not a problem with image-based memes, but rather their effectiveness as a mode of communicating ideas. Even when faced with memes that could be considered harmful, a community can use responsive memes to subvert that hateful or problematic speech. For example, some disabled communities find memes using their disabilities as a source of charity or inspiration problematic, devolving the individual into a simple stereotypes.[39] To combat this, these communities have begun using counter-memes, “taking the memes, turning the memes, planting other ideas in the memes and thus in society.”[40] This so-called “culture jamming” allows disabled people to “use as part of their own struggle to take control over their self-performance of disability, and the broader social performance of disability that contextualizes it.”[41] In the following “Chronic Illness Cat” meme, for example, the creator lays out a common stereotype for a given condition, and pushes back on that idea with a snarky response.

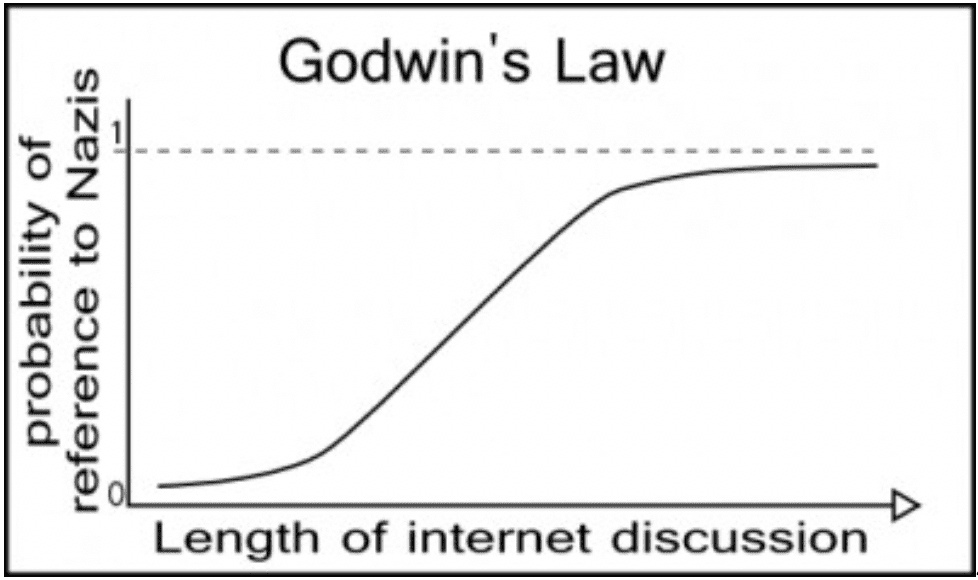

This trend of using memes as a counter to harmful speech isn’t limited to any specific topic or demographic. Godwin’s Law—the famous “law” that states “[a]s an online discussion grows longer, the probability of a comparison involving Nazi or Hitler approaches one”—is itself a meme (in the broader sense of a disseminatable slogan) designed to counter the so-called “Nazi-meme” of heated online discussion threads often devolving to name-calling.[43] As the creator himself explained in 1994, “[t]he best way to fight such memes is to craft counter-memes designed to put them in perspective.”[44]

As a part of the online ecosystem of speech and content, then, memes represent essentially a form of innovation: a new way of communicating that takes advantage of an existing technological environment (one that supports easy sharing of images with wide communities at near-zero costs), giving users of this new, innovative practice an advantage in taking their messages to the world. Like all innovations, it can be used for good and for harm. The questions, then, as with all new technologies, are whether policymakers who define the regulatory environment over memes should foster them and other innovative forms of speech, and how regulatory measures that affect the platforms on which memes live will affect this form of communication.

Lessons for Policy on Online Speech and Platforms

Based on the immense value that memes provide to a wide variety of citizens, it is our view that Congress should encourage the production and dissemination of memes as an opportunity for all communities to make their voices heard on the “vast democratic forums of the Internet.”[46] In particular, there are three lessons that Congress should consider in any discussion of online speech or Section 230, lessons that are laid out below.

Content Moderation Policies Should Encourage Open Communication and Target Speech Designed to Silence

It is vital that platforms work to protect communities like those described above, as they try to find their voice through memes or other forms of speech. It has become far too common for bad actors to seek to stifle this speech by flooding platforms with hate speech and harassment. This is especially true on platforms that take few or no steps to moderate user content.

If, for example, Senator Hawley’s bill—which would remove CDA 230 protections from companies who are not political neutral[47]— passes, platforms would need to carefully consider if removing harassing speech from one political viewpoint would make them biased in the eyes of the FTC.[48] Unfortunately, if trolls targeting a specific community tend to come from one politically ideology, moderators may choose not to remove hate speech or harassment out of a fear that it would open the entire platform up to liability,[49] avoiding any knowledge of the content generally requisite to findings of legal liability.[50] The government itself is largely hamstrung in its ability to protect these. As a result, these communities may never find the chance to gain a foothold and be drowned out by harassment and hate speech.

However, most platforms recognize this as well, and want to create an environment where their users feel safe to express themselves without fear of harassment. Indeed, many of the largest platforms have policies against this type of behavior so as to allow these communities to grow. As a part of Facebook’s community standards, for example, the company explains that “[w]e believe that all people are equal in dignity and rights. We expect that people will respect the dignity of others and not harass or degrade others.”[51] Violations of this policy subject the content to removal and the user’s account to suspension.

This is exactly the type of environment intermediary liability should attempt to foster. Platforms should not fear liability for removing users’ posts that attempt to stifle speech and community online. With certainty that their moderation decisions won’t lead to liability for all the content their users post, platforms may freely remove these posts rather than become wastelands of toxic content. This balance fosters growth on the platform and free expression online. Lawmakers should carefully consider how any shift in the law may stifle these voices.

Platforms Should Have the Flexibility to Allow Controversial yet Legal Content to Remain Online

An essential component of this debate is that what is controversial or inappropriate to some may not necessarily be controversial to others. While this may seem like a simple idea, in practice it can be hard to remember. Platforms should be encouraged to not over remove some user content just because it could be considered an offense to some.

Again, intermediary liability law plays a major role here. At the other end of the “moderator’s dilemma,” rather than leaving up all content to avoid potential liability, platforms may choose to over-remove content, silencing any voices that may possibly offend other users who could in turn sue the platforms for removal. This means that communities around controversial topics could find a significant portion of their content removed by moderators, effectively stifling their speech on these platforms.

Take, for example, the discussion of Venezuela above. Platforms may see this type of content shared within communities who disagree with the actions of the Venezuelan government potentially problematic, and even outside of Venezuela remove the content if they could face a potential lawsuit, justified or not. Rather than silence these voices, platforms should feel secure enough to allow users to share such posts and voice their opinions.

This isn’t merely hypothetical. Look at the recent actions by companies who fear retribution for their employees showing support for the protests in Hong Kong. Without wading into the debate, what this clearly shows is a different cultural understanding of what type of content is offensive and what is not. China’s state TV went as far as to say that “[w]e believe that any speech that challenges national sovereignty and social stability is not within the scope of freedom of speech.”[52] This obviously contradicts the American understanding of free speech, but it also highlights that what should and should not be removed is ultimately a subjective question, and the wrong answer can and will stifle beneficial speech online.

Also, to the extent that platforms leave disinformation up, memes can potentially serve as a rapid response strategy due to their virality and mutational nature. If a book was published with disinformation, it would take the literary press some time to discredit it, while online rants can be discredited within minutes.

Ultimately, many users will disagree about whether specific content is controversial and will seek to silence speech they disagree with. Without protections from liability, platforms will face a stronger incentive to simply remove the controversial posts even if such content is not patently offensive to many. Therefore, it is critical that intermediary liability protections allow platforms to not cave to the values of the few and over-remove content.

Platforms Should Have the Flexibility to Remove Truly Offensive Content

Despite the immense benefits that memes and speech online can provide, there are undoubtedly times in which content should be removed. Some of this content would break Federal law or violate intellectual property rights.[53] However, much of this content is not necessarily illegal, such as blatant disinformation and violent content. While intermediary liability law should encourage platforms to allow controversial posts to remain on the website, it should also allow the companies to remove content that violates platforms’ particular standards of conduct.

An intermediary liability regime that allows companies flexibility and freedom to moderate as they see fit in turn leads to competition among services. As explained above, values differ greatly among different individuals. Some users will no longer use certain platforms if disinformation or violent content remains. At the same time, other users may not stay on a platform if information is removed that they believe to be true or otherwise do not find objectionable. Therefore, if one platform decides to remove content, users who wish to see that content will likely have other places to go and share their ideas. This is a good thing.

This market-based approach allows companies to find a balance that serves their needs without impeding free speech online. Instead of a few companies with similar policies, users can go to a multitude of different sites with different policies and approaches to content moderation. This ultimately leads to the removal of much arguably inappropriate content without stifling speech outright.

Some may argue that major players like Facebook and Google do not face effective competition. But approaches that attempt to decide uniformly what content should or should not be allowed only serve to entrench these players in their current market position. If one of the major firms begins removing content because they fear losing advertisers, a niche opens. Many users will still want to see that content, and other advertisers will want to reach this audience. Platforms trying to compete can design their moderation policies to target this audience.

Also, opening up platforms to more liability will increase litigation costs for all companies in the marketplace, but the brunt of this weight will be felt by start-up and maverick firms trying to compete with the dominant players. This is because the largest firms can already bear the costs of increased litigation and regulation, but smaller firms cannot.[54] For example, after the GDPR went into effect, Europe saw decreased start-up investment, and the net winners were the large firms who could bear the compliance costs.[55]

But competition doesn’t just come from other social media platforms. News-site comments sections, for example, allow users to discuss news stories or share other information. Strong intermediary liability protections allow these sites to utilize these features to allow for more reader engagement and provide a better overall experience. While the approach to attracting users may vary significantly among competing services, these protections apply to almost all players in the online ecosystem, and overbearing regulation could serve to stifle competition and free speech online.

***

The Internet has enabled innumerable communities to create and share ideas, with image- based memes serving as an innovative way for people to connect and solve problems. Much of that success would not have been possible without protections like Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act. While companies will undoubtedly make mistakes, and bad actors may choose to allow hateful content and disinformation, the continued protection of Section 230 remains essential to ensuring the continued development of online speech in innovative forms such as Internet memes. We know not what the next steps will be in the evolution of online content, but one can be sure it will open new doors for unexpected communities that contribute to the national conversation—doors that future online content policy and platforms shouldn’t shut.

Read the original letter here.

[1] The R Street Institute is a nonprofit, nonpartisan public policy research organization, whose mission is to engage in policy research and outreach to promote free markets and limited, effective government. R Street has written significantly on content moderation and Section 230. See, e.g., Mike Godwin, SPLINTERS OF OUR DISCONTENT: HOW TO FIX SOCIAL MEDIA AND DEMOCRACY WITHOUT BREAKING THEM (2019); Jeffrey Westling, Submitted Statement for the Record, “Hearing on National Security Challenges of Artificial Intelligence, Manipulated Media, and Deepfakes Before the Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence,” June 13, 2019, https://www.rstreet.org/2019/06/13/testimony-on-deepfakes- before-the-house-permanent-select-committee-on-intelligence/; Daisy Soderberg Rivkin, “Holding the Technology Industry Hostage,” The Washington Times, July 1, 2019, https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2019/jul/1/the-stop-internet-censorship-act-would-ironically-/; Daisy Soderberg Rivkin, “How to Realistically Keep Kids Safe Online,” R Street Blog, Aug. 1, 2019, https://www.rstreet.org/2019/08/01/how-to-realistically-keep-kids-safe-online/; Shoshana Weismann, “Senator Hawley Introduces the Gold Standard of Unserious Social Media Regulation,” R Street Blog, Aug. 9, 2019, https://www.rstreet.org/2019/08/02/senator-hawley-introduces-the-gold-standard-of- unserious-social-media-regulation/.

[2] Reno v. American Civil Liberties Union, 521 U.S. 844, 868 (1997).

[3] Added original content. Original image retrieved from: https://imgflip.com/i/3cxz0t

[4] James Grimmelmann, “The Platform is the Message,” Cornell Law School Research Paper No. 18-30, March 1, 2018, p. 8. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3132758.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Stacey Lantagne, “Famous on the Internet: The Spectrum of Internet Memes and the Legal Challenge of Evolving Methods of Communications,” April 1, 2017, p. 4. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2944804.

[7] Ibid at p. 5.

[8] Caitlin Dewey, “How copyright is killing your favorite memes,” The Washington Post, Sept. 9, 2015. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-intersect/wp/2015/09/08/how-copyright-is-killing-your- favorite-memes/.

[9] Ibid.

[10] /u/honorarymancunian, “It’s all about context,” Reddit, Oct. 29, 2011. https://www.reddit.com/r/AdviceAnimals/comments/lt6nm/its_all_about_context/

[11] Ibid.

[12] Jonathan Zittrain, “Reflections on Internet Culture,” Journal of Visual Culture 13:3, Dec. 16, 2014, p. 389.

[13] Leah Shafer, “The Ups and Downs of Social Media,” Usable Knowledge, May 16, 2018. https://www.gse.harvard.edu/news/uk/18/05/ups-and-downs-social-media; Emily Weinstein, “The social media see-saw: Positive and negative influences on adolescents’ affective well-being,” New Media & Society 20:10, Feb. 21, 2018.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid; See also, “Perspectives on Harmful Speech Online: a collection of essays,” Berkman Klein Center at Harvard University, August 2017. https://cyber.harvard.edu/sites/cyber.harvard.edu/files/2017- 08_harmfulspeech.pdf

[17] Thov Reime, “Memes as Visual Tools for Precise Message Conveying,” Norwegian University of Science and Technology, 2015. https://www.ntnu.no/documents/10401/1264435841/Design+Theory+Article+-+Final+Article+-+Thov+Reime.pdf/a5d150f3-4155-43d9-ad3e-b522d92886c2.

[18] Tae Woong Park, Si-Jung Kim, & Gene Lee, “A Study of Emoticon Use in Instant Messaging from Smartphone,” Human Computer Interaction, Application and Services, 2014. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-07227-2_16.

[19] Ibid at p. 9.

[20] Elena Gonzalez-Polledo, “Chronic Media Worlds: Social Media and the Problem of Pain,” Social Media + Society, January-March 2016, p. 7. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/2056305116628887.

[21] “Where Did the Fibro Duck Idea Come From?”, Fibromyalgia Action UK, May 11, 2014, http://www.fmauk.org/latest-news-mainmenu-2/articles-1/38-fundraising-1/910-where-did-the-fibro- duck-idea-come-from.

[22] Gonzalez-Piledo, supra note 20, p. 7.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Heather Dockray, “The trans meme community on Reddit is about so much more than jokes,” Mashable, Mar. 15, 2019. https://mashable.com/article/trans-meme-subreddits/.

[26] Cameron Lister et. al., “The Laugh Model: Reframing and Rebranding Public Health Through Social Media,” American Journal of Public Health 105:11, Nov. 2015, pp. 2245-2251.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Tim Ryan, @RepTimRyan, June 2019, [Twitter post] retrieved from https://twitter.com/RepTimRyan/status/880491581970817025.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Marco Rubio, @SenRubioPress, April 2019, [Twitter post] retrieved from https://twitter.com/SenRubioPress/status/1119254514996002819

[32] Heidi E. Huntington, “Subversive Memes: Internet Memes as a Form of Visual Rhetoric,” Selected Papers of Internet Research 14.0, 2013, p. 1.

[33] Kevin Gray, Manuel Rueda, and Tim Rogers, “Venezuelan memes reflect outrage and ridicule over president’s desperation tour,” Splinter News, Jan. 2015. https://splinternews.com/venezuelan-memes- reflect-outrage-and-ridicule-over-pres-1793844820.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Jeffrey Westling, “Deception & Trust: A Deep Look At Deep Fakes,” Techdirt, Feb. 28, 2019. https://www.techdirt.com/articles/20190215/10563541601/deception-trust-deep-look-deep-fakes.shtml.

[37] Ibid.

[38] Nicholas Thompson & Issie Lapowsky, “How Russian Trolls Used Memes Warfare to Divide America,” Wired, Dec. 17, 2018. https://www.wired.com/story/russia-ira-propaganda-senate-report/.

[39] Bree Hadley, “Cheats, charity cases, and inspirations: disrupting the circulation of disability-based memes online,” Disability & Society 31:5, 2019, p. 679.

[40] Ibid at p. 685.

[41] Ibid.

[42] Melissa McGlensey, “18 Memes That Nail What It’s Like to Live with Chronic Illness,” The Mighty, Oct. 25, 2015. https://themighty.com/2015/10/best-chronic-illness-memes/

[43] Michele Knobel and Colin Lankshear, “Online Memes, Affinities, and Cultural Production,” A NEW LITERACIES SAMPLER (Peter Lang Publishing, Inc. 2007), p. 223.

[44] Mike Godwin, “Meme, Counter-meme,” Wired, Oct. 4, 1994. https://www.wired.com/1994/10/godwin- if-2/.

[45] Godwin’s Law Chart,” Know Your Meme, last visited Oct. 8, 2019. https://knowyourmeme.com/photos/39090-godwins-law.

[46] Reno v. American Civil Liberties Union, 521 U.S. 844, 868 (1997).

[47] Ending Support for Internet Censorship Act, S. 1914, 116th Cong., June 19, 2019. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/senate- bill/1914?q=%7B%22search%22%3A%5B%22internet+censorship%22%5D%7D&s=1&r=1.

[48] Daisy Soderberg Rivkin, “Holding the Technology Industry Hostage,” The Washington Times, July 1, 2019. https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2019/jul/1/the-stop-internet-censorship-act-would-ironically-/.

[49] Ibid.

[50] Jeff Kosseff, THE TWENTY-SIX WORDS THAT CREATED THE INTERNET (Cornell University Press 2019), p. 56.

[51] “Community Standards,” Facebook, last visited Oct. 10, 2019. https://www.facebook.com/communitystandards/.

[52] Arjun Kharpal, “China state TV suspends NBA broadcasts after Morey Hong Kong tweet,” CNBC, Oct. 10, 2019. https://www.cnbc.com/2019/10/08/china-state-tv-suspends-nba-broadcasts-after-morey- hong-kong-tweet.html.

[53] 47 U.S.C. § 230(e)(1)-(2).

[54] “Section 230 Cost Report,” Engine, last visited Oct. 7, 2019. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/571681753c44d835a440c8b5/t/5c8168cae5e5f04b9a30e84e/155198 4843007/Engine_Primer_230cost2019.pdf.

[55] Eline Chivot & Daniel Castro, “The EU Needs to Reform the GDPR to Remain Competitive in the Algorithmic Economy,” Center for Data Innovation, May 13, 2019. https://www.datainnovation.org/2019/05/the-eu-needs-to-reform-the-gdpr-to-remain-competitive-in-the- algorithmic-economy/; see also, Eline Chivot & Daniel Castro, “What the Evidence Shows About the Impact of GDPR After One Year,” Center for Data Innovation, June 17, 2019. https://www.datainnovation.org/2019/06/what-the-evidence-shows-about-the-impact-of-the-gdpr-after- one-year/; see also, Nick Kostov & Sam Schechner, “GDPR Has Been a Boon for Google and Facebook,” Wall Street Journal, June 17, 2019. https://www.datainnovation.org/2019/06/what-the-evidence-shows- about-the-impact-of-the-gdpr-after-one-year/.