Demand Progress FY 2022 Appropriations Public Witness Event

Thank you to Demand Progress for hosting this alternative forum for members of the government accountability community to share publicly their FY22 appropriations requests in lieu of the typical House Appropriations subcommittee process. There are few opportunities for direct participation in the federal appropriations process for those outside of the federal government and it is important to maintain this practice.

My name is Nan Swift, and I am a fellow with R Street Institute’s Governance Program. Previously, I was a staff member for the Senate Budget Committee’s Republican Staff and federal affairs manager for the National Taxpayers Union.

The R Street Institute works to promote free markets by pursuing pragmatic, often bipartisan policy solutions to some of our most pressing issues. However, we have all seen time and time again that even the best ideas cannot get off the starting blocks due to congressional dysfunction. Good policy starts with good governance—restoring the rightful role and effectiveness of our government’s First Branch. In order to do so, Congress, and the agencies that support it, must receive the resources they need to keep pace with the size and scope of our federal government.

One of those agencies is the Government Accountability Office (GAO), which celebrates its 100th birthday this year. It plays a key role in helping Congress execute its primary responsibility, the Power of the Purse. Without the constant oversight and vigilance of the GAO, Congress would have a poor understanding of what happens to taxpayer dollars after the ink is dry on the latest appropriations bill. The GAO is Congress’s watchdog, sniffing out misuse of funds and recommending reforms that could lead to better outcomes and less wasteful spending to the tune of tens of billions of dollars a year. [1]

As the federal government has grown, the GAO’s work is an increasingly essential—and increasingly burdensome—task. Unfortunately, the funding they need to maintain a suitable, sustainable workforce has not been expanded in line with the level of work they are expected to perform. For nearly two decades Congress has not responded appropriately to the conflict between congressional demands and understaffing, a situation that is exacerbated when massive new programs and spending come online during emergencies like the recent COVID-19 pandemic or the 2008 financial crisis.

As far back as 2000, then-Comptroller General David Walker testified before the House Appropriations subcommittee on the Legislative branch that, “We are 40 percent smaller today than in 1992, and congressional demands for our services have increased, a trend we anticipate will continue.” [2]

Eight years later, Comptroller General Gene Dodaro testified in his own FY 2009 budget request that their full-time staff was at 3,100, “the lowest level ever for GAO,” when only 10 years previous they had had an additional 175 employees.[3] Due to lack of available analysts, 21 percent of congressional requests were delayed and the work was taking longer to complete. Dodaro explained that “GAO staff are stretched in striving to meet Congress’s increasing needs. People are operating at a pace that cannot be sustained over the long run.”[4]

Only five years later, the situation had worsened further. Dodaro testified then, “By the end of FY 2013, GAO’s staffing level will have dropped by 463 FTE [Full Time Equivalent employee] or nearly 14 percent—a level not seen since 1935.” [5]

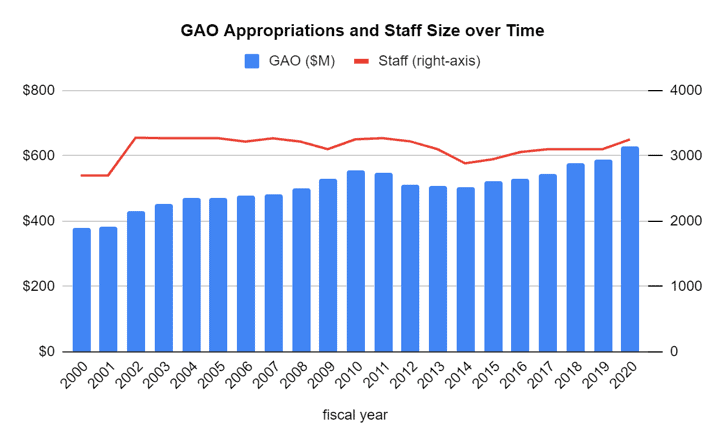

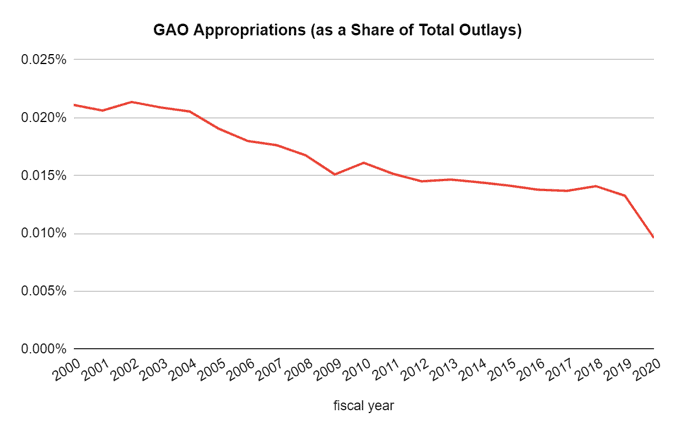

Though the 2011 Budget Control Act required belt-tightening across much of the federal government, staff levels during that period were far below what the outlays would suggest is reasonable for effective oversight.[6] This pattern has continued. By FY 2020, the GAO had a staff of 3,250 FTE responsible for almost $6.6 trillion in outlays, about four times as great as the outlays in FY 2000.[7] FTE growth in that time has increased by only around 17 percent. And GAO appropriations as a share of those total outlays continues to shrink. [See “Resources” for more information.]

This trend has troubling implications for Congress’s ability to conduct oversight and make informed spending and policy decisions. As the mandates and requests from Congress continue to outpace the GAO’s resources, it will necessitate prioritizing only those requests directly from committees or subcommittees. This will hamstring access to information for less powerful members and limit their ability to engage in the public policy process. This is already a critical problem that the House Select Committee on Congressional Modernization has tried to address.[8] In addition, the career pipeline at the GAO will suffer from lack of expertise and diversity without a consistent flow of new staff.

The legislative branch has, for many years, been the poor cousin of appropriations. It is in some ways laudable that members of Congress often set a prudent fiscal example within their own offices and committees. However, this chronic underfunding has led to many problems that hinder congressional capacity, GAO overwork among them. As the First Branch, Congress should not undermine its own effectiveness as a body.

Luckily, increasing legislative branch funding so that congressional staff, the GAO and other support agencies can meet their responsibilities does not require breaking the bank any further or complicated reshuffling across budget functions. Every year the GAO itself identifies reforms that could provide billions of dollars in savings that would be more than sufficient funding to enhance congressional capacity and improve governance.[9]

Without the strictures of the Budget Control Act, appropriators might be tempted to go on a spending spree. But the latest Long-Term Budget Outlook from the Congressional Budget Office—another key congressional support agency that should be well-resourced—warns we will soon be entering uncharted territory with debt held by the public exceeding 100 percent of GDP by the end of this year.[10] The trust funds that much of the public relies on are rapidly approaching depletion. And all this is before any of the big infrastructure and family spending packages President Joe Biden is proposing. Even prospective revenue increases will not be sufficient to pay for all the new spending, let alone what has already been promised.

Instead of simply increasing spending across the board, Congress should enact GAO recommendations and reexamine funding priorities to make sure the watchdog can keep up with the federal system it guards. As the First Branch, Congress should not just be getting appropriators’ scraps.

Thank you again to Demand Progress for hosting this important event and providing the opportunity to testify.

Nan Swift

Fellow

R Street Institute

202-525-5717

[email protected]

Resources

Image 1

Image 2

Data Sources:

- Outlays: OMB Historical Tables: https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/historical-tables/

- GAO Staff: Annual GAO budget requests: https://www.gao.gov/

- GAO Appropriations: Congressional Research Service: https://crsreports.congress.gov/search/#/?termsToSearch=legislative%20branch%20appropriations&orderBy=Relevance

- The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2021 to 2031, Congressional Budget Office, February 2021. https://www.cbo.gov/publication/56991#_idTextAnchor000

[1] Office of Public Affairs, “It’s a Federal Birthday: GAO Celebrates 100 Years of Non-partisan, Fact-Based Service to Congress and the Nation,” U.S. Government Accountability Office, Jan. 4, 2021. https://www.gao.gov/press-release/100years.

[2] Testimony of Comptroller General David Walker, U.S. General Accounting Office, “Fiscal Year 2001 Budget Request,” 106th Congress, Feb. 1, 2000. https://www.gao.gov/assets/t-ocg-00-1.pdf.

[3] Testimony of Acting Comptroller General Gene L. Dodaro, United States Government Accountability Office, “Fiscal Year 2009 Budget Request,” 110th Congress, April 30, 2008. https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-08-707t.pdf.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Testimony of Comptroller General Gene L. Dodaro, U.S. Government Accountability Office, “Fiscal Year 2014 Budget Request,” 113th Congress, May 21, 2013. https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-13-617t.pdf.

[6] S.365, Budget Control Act of 2011, 112th Cong. https://www.congress.gov/bill/112th-congress/senate-bill/365/text.

[7] Testimony of Comptroller General Gene L. Dodaro, U.S. Government Accountability Office, “Fiscal Year 2020 Budget Request,” 116th Congress, Feb. 27, 2019. https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-19-403t.pdf.

[8] Select Committee on the Modernization of Congress, Final Report, House of Representatives, 116th Congress, October 2020, Chapter 11. https://modernizecongress.house.gov/final-report-116th/chapter/chapter-11-budget-and-appropriations-reforms.

[9] 2020 Annual Report: Additional Opportunities to Reduce Fragmentation, Overlap, and Duplication and Achieve Billions in Financial Benefits, U.S. Government Accountability Office, May 19, 2020. https://files.gao.gov/reports/d230106/index.html.

[10] The 2021 Long-Term Budget Outlook, Congressional Budget Office, March 2021. https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2021-03/56977-LTBO-2021.pdf.