Comments Before the Minnesota Public Utilities Commission In the Matter of a Commission Investigation into the Potential Role of Third-Party Aggregation of Retail Customers

STATE OF MINNESOTA

BEFORE THE PUBLIC UTILITIES COMMISSION

Katie J. Sieben

Joseph K. Sullivan

Valerie Means

Matthew Schuerger

John A. Tuma

In the Matter of a Commission Investigation into the Potential Role of Third-Party Aggregation of Retail Customers

Chair

Vice Chair

Commissioner

Commissioner

Commissioner

PUC Docket Number E999/CI-22-600

Comments of the R Street Institute

The R Street Institute (“R Street”) submits these comments in response to the Notice of Comment Period, issued by the Minnesota Public Utilities Commission (“Commission or PUC”) on December 9, 2022.[1] Specifically, the Notice identifies this comment period to focus on “[s]hould the Commission take action related to third party aggregation of retail customers?”[2] The Commission seeks comments in relation to four questions related to whether the Commission should allow third-party aggregators and how, if at all, the Commission should allow them to operate in Minnesota.[3] R Street appreciates the Commission initiating this conversation on whether to allow aggregators of retail customers (ARCs) to participate in Minnesota and believes this Notice will provide much-needed information. As R Street’s comments below highlight, sufficient time has passed since the Commission last acted on this question; as such, this topic is ripe for reconsideration.

Introduction

This proceeding is the result of an order issued by the Commission in response to an application from Xcel Energy related to several proposals to add a performance-based incentive to new demand response proposals.[4] In the order approving the demand response programs, but denying the performance-based incentive, the Commission directed the Executive Secretary to initiate a new proceeding on third-party ARCs. To help the Commission consider potential action related to third-party ARCs in Minnesota, the Commission is seeking comments on four questions:

Question 1: Should the Commission permit aggregators of retail customers to bid demand response into organized markets?

Question 2: Should the Commission require rate-regulated electric utilities to create tariffs allowing third-party aggregators to participate in utility demand response programs?

Question 3: Should the Commission verify or certify aggregators of retail customers for demand response or distributed energy resources before they are permitted to operate, and if so, how?

Question 4: Are any additional consumer protections necessary if aggregators of retail customers are permitted to operate?

Comments

R Street thanks the Commission for seeking input on these important procedural considerations. R Street believes that this is an opportune time for the Commission to have this discussion regarding the ability of ARCs to participate in Minnesota. R Street recommends that the Commission continue this proceeding to develop appropriate rules to allow ARCs to participate in Minnesota.

Question 1: Should the Commission permit aggregators of retail customers to bid demand response into organized markets?

In short, yes. The Commission’s last substantive action on ARCs was in 2013.[5] There has been significant changes in the electricity system over the last 10 years, additional action before the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) directing regional transmission organization (RTOs) to allow distributed energy resources aggregators (DERAs) to participate in wholesale markets.[6] Additionally, FERC Order No. 745 was upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court after the Commission’s last action on ARCs.[7] Finally, FERC has taken steps to reconsider the initial decision in Order No. 719 that let states opt out of allowing ARCs to provide demand response services to operate in their states.[8] This opt-out creates challenges for implementing Order No. 2222 as the opt-out only applies to demand response services. This means that an ARC that is allowed to operate pursuant to Order No. 2222 by aggregating energy efficiency, storage or any other wholesale service cannot include demand response. FERC sought to address this confusion in Order No. 2222-B by allowing demand response to be included in heterogeneous aggregations.[9] According to FERC, a purpose of Order No. 2222 is to “break down barriers to competition.”[10] While FERC subsequently withdrew the direction to allow demand response to be part of heterogeneous aggregations in Order No. 2222-B, it did not explicitly reject its determination on the value of demand response being included in heterogeneous aggregations; rather, FERC decided to open a new proceeding to consider whether to maintain the demand response opt-out that was granted in Order No. 719.[11] In order to minimize this confusion, R Street believes that the Commission can best mitigate this by removing the prohibition on ARCs to participate in Minnesota, which would, under state guidance, allow ARCs to participate in wholesale markets more fully. This would allow ARCs to develop aggregations that include demand response, both on a stand-alone basis and as part of a heterogeneous aggregation. Such action is allowed under Order No. 719 and would fulfill the overarching goals of both Order No. 745 and Order No. 2222 to enhance competition in wholesale markets.

In Minnesota, the Commission has directed utilities to increase the amounts of demand response to be used, including directing Xcel Energy to procure an additional 400 megawatts (MWs) of demand response as part of its most recent integrated resource plan.[12] It was this requirement that resulted in Xcel filing a proposal to develop 48 MWs of demand response paired with a performance-based incentive in Docket No. 21-101.[13] In its order on Xcel’s Petition, the Commission rejected the performance-based incentive, but it approved most of Xcel’s proposed demand response programs with one important modification: it expanded the proposed Peak Flex Credit pilot to allow ARCs to provide an additional 43 MWs of demand response.[14] In that decision, the Commission found that “third-party aggregation of retail customers could facilitate broader participation and scale of demand response programs and improve compliance with control events, potentially expanding the utility’s demand-response capability and associated system benefits while advancing state energy policy goals.”[15] Here, the Commission explicitly recognizes that aggregators can play a role in developing more demand response across the state and that such actions are important to meet Minnesota’s carbon and climate goals. Notably, Gov. Tim Walz recently signed a law setting a requirement for Minnesota’s electricity system to be 100 percent carbon free by 2040.[16] R Street believes that distributed energy resources, including demand response, and services developed by ARCs, can play a significant role in meeting this target.

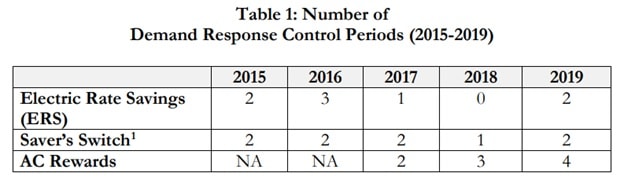

Importantly, however, is the question of how demand response is used in Minnesota. While traditional utility demand response programs sign up customers and give those customers a discount on their bills, for the utility, these programs accrue to their capacity obligations. To the extent these programs are offered into wholesale markets, they are mostly considered emergency programs and only called upon for a system emergency. This means that for most, if not all, of the year, utility demand response programs remain uncalled by the utility or the Midcontinent Independent System Operator (MISO). In January 2020, Commission Staff sought information from Xcel regarding its demand response programs, when they were called by Xcel, and if those programs were dispatched in alignment with MISO peak periods for the years 2015-2019. Xcel included the following table:

This table shows that Xcel has called its programs a few times each year for this time period.[17] However, only one of these events was called in response to a direction from MISO; all other events were test events.[18] This means, in other words, that for the five-year period of 2015-2019, Xcel only called its demand response program once in response to a grid need.

In another information request, Commission Staff asked Xcel to “identify the five time periods of highest power costs and explain whether [demand side management programs] was called at that time and why.”[19] In its response, Xcel noted that only one time during that five year period did it call on demand response during a high-cost period.[20] Furthermore, Xcel stated that “[t]he value of demand response programs does not come from how often it is used, but is derived from the option to use it. This benefit will accrue to our customers regardless of the frequency or timing of calling of Demand Response Events.”[21] While R Street recognizes the capacity value that demand response brings, even if those programs remain uncalled, at the same time, not dispatching demand response results in higher wholesale prices.

Xcel further noted that “MISO LMPs are a function of not only energy supply and demand, but also market congestion and losses, and the activation of demand response resources may not always provide economic benefit to customers.”[22] This is a remarkable statement. Demand response programs help customers by reducing not only customer bills, but overall wholesale market costs. If there is congestion, then demand response can alleviate that congestion by reducing demand at those locations. To the extent that MISO products do not adequately capture or pay for that value, that is an issue for MISO, not necessarily for the Commission in determining whether aggregators can develop more innovative demand response programs.

Finally, there has been significant innovation in the demand response space since 2013. Energy storage, electric vehicles, advanced technologies such as smart thermostats, and distributed solar all offer more opportunities to participate directly in wholesale markets and provide additional services, including demand response. In some cases, this may mean increasing consumption in response to oversupply events. To the extent that the utilities are only considering demand response as load reduction, that view may unnecessarily limit the potential value of demand response. In other words, the Commission should consider demand response as providing utilities and the wholesale market with a variety of potential services that is no longer limited only to reducing consumption.[23] With more electric vehicles and distributed solar, the system may encounter periods of excess supply where it is necessary to either curtail generation or increase consumption. As seen in other states, like California, as solar deployment increases, there may be times of the year where there is an excess amount of electricity. During those time periods, consuming that excess electricity generated by solar will enhance the efficiency of the system and avoid the curtailment of solar resources. The utility, on the other hand, has less incentive to develop such opportunities as distributed solar competes with utility-owned generation. The Commission should consider how to enable a more efficient and cost-effective electricity system. Included in that determination is the role that aggregators can play in supporting this goal as aggregators have an incentive to sign up customers and have those programs be used. Rather than not calling demand response programs for years, aggregators have the ability to work with customers who may want more flexibility and be compensated for that flexibility. The need for such flexibility is likely to increase with more distributed energy resources, solar and wind. As such, the Commission should allow aggregators to participate in Minnesota and permit them to participate in wholesale markets.

Question 2: Should the Commission require rate-regulated electric utilities to create tariffs allowing third-party aggregators to participate in utility demand response programs?

To the extent that the Commission decides to allow aggregators to operate in Minnesota, then R Street suggests that the Commission should not limit opportunities for aggregators. This means that aggregators should be allowed to participate in wholesale markets and in retail markets, such as through utility tariffs. Furthermore, R Street would encourage the Commission to ensure that aggregators are able to participate in utility requests for proposals for new system needs. All resource procurements are an important market-based approach to ensure that the utility is considering all available options to meet future resource needs. Considering the recently passed 100 percent carbon free bill, the Commission should ensure that Minnesota’s utilities look at all available resources, including procuring demand response from aggregators, to meet future resource needs.

However, it should be noted that this option has been available to utilities and aggregators since 2011, with little success. Only until recently, with the Commission’s expansion of Xcel’s Peak Flex Credit pilot, has there been an effort to consider the roles of aggregators to participate in existing utility demand response tariffs, and, again, this was done at the direction of the Commission. It seems clear that this Commission finds the utilities’ approach to demand response lacking and is doing what it can to enable greater amounts of demand response. One concern is that utility retail demand response programs may not provide sufficient opportunities for aggregators to participate or provide adequate compensation to customers for participation. For example, if utility demand response programs remain uncalled or simply submitted into the MISO market as emergency programs, this will not provide enough opportunities for aggregators to participate.

Indeed, in the Xcel demand response performance-based incentive proposal, the Peak Flex Credit pilot, one of the areas being tested was economic response to a price signal. In that pilot, the price signal was defined as “high Locational Marginal Pricing (LMP) within the generation market. These events will occur when the MISO day-ahead hourly LMP levels applicable for the Xcel Energy load zone exceeds typical levels as determined by the Company.”[24] It is important to note that the LMPs in the MISO market are aggregations of more distributed price signals—also called elemental pricing nodes, or Pnodes. This means that the LMP is an aggregation of all the Pnodes in the Xcel service territory. This, then, fails to account for opportunities on a locational basis to alleviate congestion, for example. If the Commission is interested in allowing aggregators to participate in retail programs, R Street suggests that the utilities develop programs that will reduce prices at locations below the LMP across the state. While there may be benefit for geographically broad retail programs, limiting demand response opportunities only to service-territory wide LMPs means that:

1) there are missed opportunities to develop demand response in high-priced Pnodes; and

2) the ability of aggregators and customers to be fairly compensated for their value to the grid is diluted.

R Street supports allowing aggregators to participate in utility retail demand response tariffs, but recommends that the Commission encourage utilities to develop new retail demand response programs that can be more responsive to price signals.

Question 3: Should the Commission verify or certify aggregators of retail customers for demand response or distributed energy resources before they are permitted to operate, and if so, how?

In order to have a well-functioning and trusted market-place for ARCs to participate in Minnesota, R Street believes that the Commission should adopt rules and tariffs to enable ARC participation. R Street sees the role of ARC registration and the development of rules and tariffs to provide certainty to ARCs, utilities, the Commission and customers regarding the operation of ARCs. Furthermore, R Street notes that any rule and tariff that is adopted should be applied in the same manner for each utility under Commission authority. Such conformity is vital to ensuring that aggregators can operate in Minnesota with one set of rules rather that multiple, utility-specific requirements. This consistency will reduce overhead and customer acquisition costs for the ARCs and will ensure that individual utility practices is not a barrier to entry.

As a starting point, R Street suggests that the Commission look to the rules adopted by the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) related to demand response aggregators that operate in California.[25] In order for an ARC to participate in California, an aggregator must be registered with the CPUC, along with the California Independent System Operator (CAISO). For purposes of these comments, R Street will only focus on the state regulatory requirements adopted by the CPUC. Accordingly, the requirements adopted by the CPUC include:

1) A signed demand response provider (DRP) registration form;

2) An application fee of $100 via certified check;

3) A signed ultility-DRP service agreement for each utility territory that the DRP intends to do business in; and

4) A performance bond if the aggregator intends to serve residential or small commercial customers (of less than 20 kilowatt (kW) peak load). The performance bond amount is based on the number of customers according to a formula in each of the utility’s rules. The minimum performance bond amount is $25,000.[26]

By requiring such information, the Commission is able to identify authorized ARCs; have contact information for all authorized ARCs; ensure that the ARCs agree to abide by the adopted policies and rules of the Commission; and provide additional protection for ARCs that work with residential and small commercial customers.[27]

Furthermore, by adopting requirements, as found in PG&E Electric Rule No. 24, the Commission provides certainty to ARCs and the utilities regarding the rights, roles and responsibilities of each organization. Such rules include:

- a common set of definitions;

- timelines for approval and communications between the ARC and the utility;

- participation requirements for customers to minimize risk of dual participation in the same products;

- the availability of customer energy usage data;

- how to establish aggregation service;

- any costs that need to be paid in the provision of certain services (such as metering);

- the process for a customer to discontinue participation in either a utility demand response program or an aggregator’s program; and

- a dispute resolution process.

R Street is concerned that if these rules, roles and responsibilities are not detailed in advance, the Commission may find itself needing to litigate these issues individually and as they occur, on a utility-by-utility basis, which would not be beneficial to customers, ARCs, utilities or the Commission. Rather, by comprehensively addressing these issues in advance and in one document, the Commission can detail the roles of the ARCs and utilities, and set expectations for how aggregation will occur.

R Street does want to raise a specific issue at this time related to the availability of customer energy usage data. To date, the Commission has held numerous proceedings and workshops on enabling and facilitating the sharing of customer energy usage data to customer-authorized third parties. In Docket No. E, G999/CI-12-1344, the Commission considered a number of potential actions related to the sharing of customer energy usage data. On Aug. 24, 2016, Chief Judge Tammy Pust issued the “Second Report of the Customer Energy Usage Data Workgroup.”[28] The Second Privacy Report contained several recommendations, including the need to develop a Minnesota-specific data sharing framework.[29] The need for access to customer data was identified in the Commission Staff’s Report on Grid Modernization as well.[30] As stated by Staff, “[a]vailability of customer usage information in a standardized format supports market development for customer-sited services and products, including enhanced energy efficiency opportunities for customers,” and that “Staff believes customer usage information is a key component of enabling greater benefits from grid modernization.”[31] The lack of formalized data access policy and the lack of required use of standards to enable data sharing, such as via Green Button Connect My Data, may hamper the ability of ARCs at the start. However, in the Second Privacy Report, Commission Staff drafted a document that proposed a set of principles and a framework to enable the sharing of customer energy usage data with customer-authorized third parties.[32] While the Second Privacy Report outlines the issues raised by participants regarding the draft principles and framework, it was noted that due to time limitations, the stakeholders decided to shift to other topics.[33] Nevertheless, R Street suggests that the Commission reconsider the work already completed to date by the Commission, Commission Staff and stakeholders to address this significant area of need. While development of a comprehensive data access and privacy policy may not have been urgent at the time of the Second Privacy Report, without such a document today, R Street anticipates that the lack of such policies will make it challenging for the aggregator market to get established.

Finally, R Street encourages the Commission to ensure that any action related to development of data access and privacy policies be consistent across each regulated utility. This would include adoption of Green Button Connect My Data and ensuring that such implementation is done in compliance with the underlying standard. A significant barrier to the enablement of aggregators is if each utility in a given jurisdiction has different rules, policies and requirements. In other words, if an aggregator wants to participate in Minnesota, but Otter Tail, Minnesota Power and Xcel each have different policies related to accessing customer data, the means by which data is shared with an authorized third party, or is otherwise not in compliance with the underlying standard, the greater the cost to the aggregator.

Question 4: Are any additional consumer protections necessary if aggregators of retail customers are permitted to operate?

R Street reiterates the importance of developing a common set of rules to be adopted and implemented by each regulated utility. The adoption of such rules would be included in the utilities’ tariff book, and it is via that tariff that the Commission is able to exercise a limited amount of authority. Such authority, however, is limited as ARCs are not providers of electricity. Therefore, its jurisdiction is limited to its authority over the application and implementation of utility tariffs. It is via this mechanism that the California Commission ensures that an aggregator follows both the aggregator rules (see PG&E Electric Rule No. 24) and the data access rules (see PG&E Electric Rule Nos. 25 and 27.1).[34] If the Commission then finds an aggregator in violation of such rules, the Commission can direct the utility to revoke that aggregators’ access to customer data and participate as an ARC in Minnesota. That aggregator would then be added to a list of aggregators that are not allowed to participate in Minnesota.

Conclusion

R Street thanks the Commission for the opportunity to provide these comments on the questions of allowing aggregators to operate in Minnesota.

Respectfully submitted,

___/s/ Christopher Villarreal____

Christopher Villarreal

Non-Resident Energy Policy Fellow

The R Street Institute

1212 New York Ave. NW Suite 900

Washington, D.C. 20005

415-680-4224

cvillarreal@rstreet.org

March 13, 2023

Read all the comments here:

[1] In the Matter of a Commission Investigation into the Potential Role of Third-Party Aggregation of Retail Customers, Notice of Comment Period, Docket No. E999/CI-22-600 (Dec. 9, 2022) (Notice). On February 6, 2023, the Commission issued a subsequent notice extending the due date for initial comments to March 13, 2023.

[2] Id. at 1.

[3] Id.

[4] Id. See also, In the Matter of Xcel Energy’s Petition for Load Flexibility Pilot Programs and Financial Incentive, Order Approving Modified Load-Flexibility Pilots and Demonstration Projects, Authorizing Deferred Accounting, and Taking Other Action, Docket No. E002/M-21-101 (March 15, 2022).

[5] In the Matter of an Investigation of Whether the Commission Should Take Action on Demand Response Bid Directly into the MISO Markets by Aggregators of Retail Customers Under FERC Orders 719 and 719-A, Order Accepting Compliance Filings, Docket No. 09-1449 (April 16, 2013).

[6] Participation of Distributed Energy Res. Aggregations in Mkts. Operated by Reg’l Transmission Orgs. & Indepe. Sys. Operators, Order No. 2222, 172 FERC ¶ 61,247 (2020), order on reh’g, Order No. 2222-A, 174 FERC ¶ 61,197, order on reh’g, Order No. 2222-B, 175 FERC ¶ 61,227 (2021).

[7] Demand Response Compensation in Organized Wholesale Energy Mkts., Order No. 745, 134 FERC ¶ 61,187 (2011), order on reh’g & clarification, Order No. 745-A, 137 FERC ¶ 61,215 (2011), reh’g denied, Order No. 745-B, 138 FERC ¶ 61,148 (2012), vacated sub nom. Elec. Power Supply Ass’n v. FERC, 753 F.3d 216 (D.C. Cir. 2014), rev’d & remanded sub nom. Elec. Power Supply Ass’n v. FERC, 136 S. Ct. 760 (2016).

[8] Participation of Aggregators of Retail Demand Response Customers in Markets Operated by Regional Transmission Organizations and Independent System Operators, 174 FERC ¶ 61,198 (March 18, 2021).

[9] Order No. 2222-A at P 28.

[10] Order No. 2222-A at P 23.

[11] Order No. 2222-B at P 28.

[12] In the Matter of Xcel Energy’s 2016–2030 Integrated Resource Plan, Order Approving Plan with Modifications and Establishing Requirements for Future Resource Plan Filings, Docket No. E002/RP-15-21 (January 11, 2017).

[13] Petition for Load Flexibility Pilot Programs and Financial Incentive, Docket No. E002/M-21-101 (February 1, 2021).

[14] In the Matter of Xcel Energy’s Petition for Load Flexibility Pilot Programs and Financial Incentive, Order Approving Modified Load-Flexibility Pilots and Demonstration Projects, Authorizing Deferred Accounting, and Taking Other Action, Docket No. E002/M-21-101 (March 15, 2022).

[15] Id. at 9.

[16] Office of Governor Tim Walz and Lt. Governor Peggy Flanagan, “Governor Walz Signs Bill Moving Minnesota to 100 Percent Clean Energy by 2040,” State of Minnesota, Feb. 7, 2023. https://mn.gov/governor/news/?id=1055-563453.

[17] Xcel Response to Staff Information Request No. 3, Docket No. E002/CI-17-401 (Jan. 17, 2020). Included as Attachment A.

[18] Id. at Table 2.

[19] Xcel Response to Staff Information Request No. 4, Docket No. E002/CI-17-401 (Jan. 17, 2020). Included as Attachment B.

[20] Id. at 1-2.

[21] Id. at 1.

[22] Id. at 2.

[23] See, e.g., Application of Pacific Gas and Electric Company (U39E) for Approval of Demand Response Programs, Pilots and Budgets for Program Years 2018-2022, Decision Adopting Demand Response Activities and Budgets for 2018 through 2022, D.17-12-003, California Public Utilities Commission (December 21, 2017) (defining demand response as “reductions, increases, or shifts in electricity consumption by customers in response to either economic signals or reliability signals. Economic signals come in the form of electricity prices or financial incentives, whereas reliability signals appear as alerts when the electric grid is under stress and vulnerable to high prices. Demand response programs aim to respond to these signals and maximize ratepayer benefit.” D.17-12-003 at 3). https://docs.cpuc.ca.gov/PublishedDocs/Published/G000/M202/K275/202275258.PDF.

[24] Xcel Petition at 16.

[25] Order Instituting Rulemaking regarding policies and protocols for demand response load impact estimates, cost-effectiveness methodologies, megawatt goals and alignment with California Independent System Operator Market Design Protocols, D.12-11-025, California Public Utilities Commission (Dec. 4, 2012). https://docs.cpuc.ca.gov/PublishedDocs/Published/G000/M037/K494/37494080.PDF See also, PG&E Electric Rule No. 24. https://www.pge.com/tariffs/assets/pdf/tariffbook/ELEC_RULES_24.pdf. All references to the California rule will be to PG&E Electric Rule No. 24 unless otherwise identified.

[26] California Public Utilities Commission, “DRP Registration Information,” State of California, last accessed March 5, 2023. https://www.cpuc.ca.gov/industries-and-topics/electrical-energy/electric-costs/demand-response-dr/drp-registration-information. Examples of needed forms can be found at the same link.

[27] See, e.g., the list of registered aggregators with the CPUC: https://www.cpuc.ca.gov/industries-and-topics/electrical-energy/electric-costs/demand-response-dr/registered-demand-response-providers-drps-aggregators-and-faq.

[28] In the Matter of a Commission Inquiry into Privacy Policies of Rate- Regulated Energy Utilities, Second Report of the Customer Energy Usage Data Workgroup, Docket No. E,G999/CI-12-1344 (Aug. 24, 2016) (Second Privacy Report). https://efiling.web.commerce.state.mn.us/edockets/searchDocuments.do?method=showPoup&documentId={833E041A-0EFD-4A91-91C1-0503F4F08970}&documentTitle=20168-124392-01.

[29] Second Privacy Report at 7.

[30] Staff Report on Grid Modernization, Minnesota Public Utilities Commission (March 2016) (Staff Report). https://www.edockets.state.mn.us/EFiling/edockets/searchDocuments.do?method=showPoup&documentId={E04F7495-01E6-49EA-965E-21E8F0DD2D2A}&documentTitle=20163-119406-01.

[31] Id. at 27.

[32] Second Privacy Report at Exhibit E.

[33] Id. at 11.

[34] PG&E Electric Rule No. 25 is available at: https://www.pge.com/tariffs/assets/pdf/tariffbook/ELEC_RULES_25.pdf. PG&E Electric Rule No. 27.1 is available at: https://www.pge.com/tariffs/assets/pdf/tariffbook/ELEC_RULES_27.1.pdf.