R Street Institute Regulatory Comment on Executive Order Regarding Competition in the Beer, Wine, and Spirits Markets

The following comments are respectfully submitted in response to the Request for Information relating to Promoting Competition in the Beer, Wine, and Spirits Markets [Docket No. TTB-2021-0007; Notice No. 204].

The current presidential administration’s July 9, 2021 Executive Order on Promoting Competition in the American Economy [EO 14036] calls for an assessment of “the conditions of competition” for beer, wine and spirits, including “any threats to competition and barriers to new entrants.”[1] This encompasses analysis of “unlawful trade practices, patterns of consolidation in production, distribution, or retail markets, and regulations pertaining to such things as bottle sizes, permitting, or labeling that may unnecessarily inhibit competition.”[2] The Treasury Secretary, via the Administrator of the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB), has been given the responsibility to make decisions on updating or revising regulations that “unnecessarily hinder competition,” and to reduce “any barriers that impede market access for smaller and independent brewers, winemakers, and distilleries.”[3]

These are worthwhile issues to consider as all Americans are interested in a healthy, robust, competitive alcohol market. But it is vitally important to ask the right questions, focus on the right issues, and, if needed, adopt the right solutions. In other words, what outcomes have we not been able to achieve and what stands in the way? It is true that outdated laws and regulations stand in the way of competition and act as barriers for new entrants. And robust discussions concerning alcohol as a legal, regulated product have been lacking—and sometimes even discouraged—yet are needed going forward in the alcohol sector. But when the wrong questions are the centerpiece of discussions, then conversations can become the center of controversy rather than solutions.

It is also critical to understand the history of alcohol beverage markets and how they have developed over time in the United States. In the aftermath of Prohibition, many policymakers remained concerned about access to alcohol and sought to control how it was sold to consumers. Fears about the potential for vertical monopolies to form, in which a single alcohol producer would own and control all the retail sales of alcohol within certain regions, led to the implementation of control states and/or the three-tier system in every state.[4]

This framework was designed to prevent so-called “tied houses,” in which one tier of the alcohol market supply chain could own or control another tier. At that time in history, insertion of this middle tier was meant to ensure robust product choices and dilution of market control between manufacturers and retailers. Therefore, state governments decided either to operate and control the wholesale or retail tiers as a market participant gaining revenues for the state, or to require private producers, wholesalers and retailers to be licensed and legally separate entities.[5]

In many ways, one can argue that alcohol markets are unique in the American economy for two reasons: The legal structure governing the industry was explicitly developed to prevent the formation of monopolies, and the bulk of governmental oversight of the industry in the post-Prohibition era has resided at the sub-national level. It is critical to understand this context when analyzing competitive issues and concerns about consolidation in this industry.

It is equally critical to understand how alcoholic beverage markets have changed and evolved over time. The industry has changed tremendously since the Prohibition era—now close to a century in the rear-view mirror—and policymakers must remain cognizant of both where the industry came from and where it is going in order to enact laws and regulations focusing on legitimate government interests, rather than merely protecting the status quo as the world moves forward into the next hundred years.[6]

Producer-Level Concentration

To date, much of the focus in the alcohol world when it comes to competition and consolidation issues has been focused on the producer level. In recent years, numerous members of Congress have called for increased antitrust scrutiny of the alcohol industry over concerns of monopoly formation in the wake of high-profile producer mergers.[7] Likewise, the current administration, in an explanatory blog post issued the same day as the EO on competition, cited a study about a 2016 acquisition in the beer industry that some argued led to higher beer prices (this specific acquisition has already been scrutinized by the Department of Justice for antitrust concerns and a settlement was reached).[8]

The media has also highlighted numerous stories about producer-level consolidation in the alcohol industry. Many of these have been focused on global consolidation patterns, but some have looked at the United States more specifically.[9] At the very least, the fragmented nature of the three-tier structure requires careful scrutiny of where consolidation issues are most pronounced.

Of note, some of the most nuanced analyses warning about producer-level consolidation focus on shelf-space at retail outlets, citing fears that one or two producers—and their subsidiaries—dominate the brands offered in the beer aisle of most grocery stores.[10] These critics cite the alleged influence that large alcohol producers have over certain distributors that carry their products, which they argue could result in those distributors giving preference to products from specific producers at the expense of other producers. In turn, these distributors allegedly focus on selling the specific producer’s products to retailers, reducing the retail shelf space for other producers.

In other words, much of the producer-level competition concerns in the alcohol marketplace could in fact be viewed as a distributor-level problem. To the extent that distributors do preference specific producers over others, state laws often prevent discontented producers from being able to choose new distributors that would treat them more equitably.[11]

Embedded within the laws of most states are protectionist features like “exclusive territories,” which grant wholesalers exclusive sales rights over specific geographical regions, and stringent “franchise laws,” which make it extremely difficult, if not impossible, for producers to exit contracts with their wholesalers.[12] These baked-in legal structures, by their nature, create an environment in which alcohol distributors can wield incredible power within the industry and control which products are made available at retail outlets. Through these contracts, distributors pick and choose the allocation of markets and choices for retailers and consumers, which raises the question: At what point does this become an unreasonable restraint of trade?

Furthermore, the three-tier system itself, which legally requires producers to use a wholesaler in order to get their products stocked in retail stores, prevents a natural market-oriented response to counteract these inherently anti-competitive legal structures. Specifically, it prevents small, independent alcohol producers from simply self-distributing directly to local retailers and thereby circumventing distributors that neglect their products.[13] The result is that states often embed anti-competitive legal structures at the wholesale level within their state codes, which can limit market access for many producers.

The administration, in the blog post accompanying the EO on competition, provided specific definitions for various terms relating to market dominance. It defines “monopoly” and “monopsony” as well as “winner take all” markets in which “a single firm tends to dominate, even if the dominant firm’s product is only slightly better than the other products, and the market may have originally been competitive.”[14] It further specifies that in “winner take all” markets, the “market becomes more concentrated when the best performers are able to capture a large share of the market, often through technological advances.”[15] Finally, the post points to studies showing that “local concentration” in markets has been declining in recent years as larger national companies have started entering—and dominating—local markets.[16] The EO also specifies a focus on patterns of consolidation, suggesting a further emphasis of whether a market is becoming more or less consolidated over time.[17]

To discern whether alcohol market “patterns of consolidation” have become “more concentrated,” one can look at the various trends in market concentration for each tier of the alcohol sector. Importantly, this reflects a key aspect of market consolidation analysis: If the market share of smaller firms is increasing over time, that is indicative of a market amenable to new market entrants, thus undermining concerns about an overly consolidated marketplace. In other words, rather than top-line market share numbers, the patterns of how those numbers are trending over time can provide the most salient data for determining if a marketplace is healthy and competitive. The number of new entrants into a market is also a critical factor in determining the competitiveness of a market.

To underscore its focus on whether an industry’s consolidation levels are increasing or decreasing, the administration added in its fact sheet accompanying the EO: “For decades, corporate consolidation has been accelerating. In over 75% of U.S. industries, a smaller number of large companies now control more of the business than they did twenty years ago.”[18]

At the producer level, the alcohol industry has become less consolidated over time. In the beer market—the one most often associated with consolidation concerns—market share has shifted from large brewers to small brewers by at least 5 percent since 2010.[19] The explosive rise of the craft beer revolution can be credited with this trend. In 2004, craft beer made up 5 percent of the American take-home beer market, but by 2018 craft brewers had “more than doubled their volume share to 12 percent and quadrupled their revenue share to 20 percent.”[20] In 2019, the retail dollar value market share of craft beer grew to 25.2 percent, a 6 percent increase from 2018. [21] Likewise, the market share by volume for craft beer grew to 13.6 percent in 2019, up from 13 percent in 2018 and 12.5 percent in 2017.[22] (It is worth noting that in 2020, craft beer’s market share by volume decreased to 12.3 percent; the proximate cause of this decrease was COVID-19-related shutdowns and social distancing orders, which disproportionately hurt small brewers that make up a substantial portion of sales in their taprooms, and which can be expected to alleviate as lockdowns are lifted).[23]

The number of breweries in America has also grown at an explosive rate over the past few decades. In 1991, there were 312 breweries in America; in 2020, there were 8,884 (of these breweries, only 120 are categorized as non-craft/large breweries).[24] Other small alcohol producers, such as craft distillers, have also seen increases in growth in recent years: As of August 2019, there were over 2,000 craft distillers and overall market share was continuing to increase for these distillers.[25] (Market concentration analysis of the wine industry is more difficult given the varieties of wine and definitional issues over how products like ciders and meads are counted, although it is clear the number of wineries has also drastically increased in recent years.) [26]

This data tells a story of a rapidly evolving marketplace for alcohol producers. It is a market that has seen a jaw-dropping number of new market entrants over the past few decades, and a gradual decline in the market share of the largest firms. Importantly, the predominant drivers of a more diverse and less consolidated producer-level alcohol market were the growth of digital advertising, the rise of the millennial generation and timely government deregulation (such as the legalization of home brewing in 1978 and the spread of state-level brewpub and tasting room laws in the 1980s-90s).[27] As one analysis summarized:

“The takeoff in craft brewing is not a coincidence. Deregulation and low-cost digital advertising made it easier for new craft-beer players to enter the market, especially since the late 1990s. As a result, millennials have had access to craft alternatives since they turned 21, whereas older generations first encountered those long after they had established a preference for national brands.”[28]

It begs the question: If market consolidation concerns were not deemed relevant for alcohol producers two or three decades ago when there were only a few hundred firms and a larger share of market concentration amongst large producers, how does it make sense today in an environment where thousands of firms exist and the market share of the largest firms has been decreasing overall?

Under the administration’s guidance, it also can be worthwhile to analyze whether “local concentration” in alcohol markets has declined within an industry on account of large national firms taking over local markets. Numerous features of alcohol markets make it highly unlikely that a national firm would be able to capture and maintain undue dominance in local markets. From the outset, it is important to highlight the intense rise of so-called “neolocalism” in the alcoholic beverage industry. Neolocalism is broadly defined as the “conscious effort by businesses to foster a sense of place based on attributes of their community.”[29] Craft alcohol producers are seen as “important actors in this movement.”[30]

As one study put it:

Looking for the sense of and connection to place is behind the strong pull of hometown loyalty and yearning that encourages people to buy locally brewed beer. Mike Foley, at the time the president of Heineken USA, stated that “people are looking for something very different as part of a behavioral statement (…) With a micro, they’re not drinking a brand at all, but an idea.”[31]

This emphasis on localism and sense of place is only expected to accelerate given that the millennial generation, more than its predecessors, places an especially strong emphasis on local businesses and community connection.[32] It is therefore unsurprising that research has demonstrated that consumers exhibit a noted preference for local beer, and are willing to pay more for local craft alcohol products.[33] The millennial preference for craft beer over large national brands has led researchers to suggest that beer markets will become even more fragmented over the next decade.[34] This inherently makes it difficult for an outside, national producer to exercise dominance over local markets.

Another facet of the craft beverage market is the growing consumer preference for the new and different. Some breweries have seen sales for flagship beers fall, as drinkers want a constant array of new releases and rotating taps.[35] This consumer drive for ever-varying beer further fragments the marketplace away from big, national producers, and reduces accretions of power in one specific type or brand of beer. So far there has been less research conducted on localism outside of beer, but it appears to be an increasingly important factor across all alcoholic beverage types.[36]

Based on these trends in market share, new market entrants and the lack of local market dominance by national firms, concerns over producer-level market concentration do not appear to be as pronounced as many commentators have suggested. Further, the ongoing reality that alcohol remains predominantly regulated at the sub-national level—via control states and three-tier systems, which, again, were explicitly designed to prevent undue market concentration—provides another reason for caution by federal government regulators.

The 21st Amendment, however, does not allow states to act without scrutiny. The U.S. Supreme Court recently made it clear that the 21st Amendment does not rescue every state action and that protectionism is not a legitimate purpose for regulating alcohol markets.[37] Further, it is also clear that other federal statutes, such as the Commerce Clause, must be applied in conjunction with the 21st Amendment. These are also important concepts to keep in mind while analyzing market concentration.

Wholesaler-Level Concentration

In contrast to the producer-level, where the trends have been toward less market concentration as the market share of small producers has grown in recent years, the wholesaler tier has seen a pattern toward more market concentration.

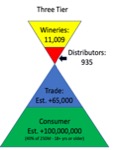

This consolidation can be seen for all varieties of beverage alcohol—wine, distilled spirits and beer. The same wholesalers often distribute both wine and spirits, and as one recent wine industry survey noted: “The proliferating number of North American wineries has an inverse correlation with the shrinking number of distributors. According to winery and distributor sources, in 1995 the United States had about 1,800 wineries and 3,000 distributors. Today [2017], there are more than 9,200 wineries and nearly 1,200 distributors.”[38]

A more recent analysis from 2021 found under one thousand wine distributors, and included a stunning graphic that illustrates market concentration levels across all tiers of the wine industry:

Source: Protea Financial[39]

The beer industry shows similar trends, as the number of beer wholesalers decreased from 4,595 in 1980 to 3,000 by 2020.[40]

Also, unlike the producer level, the market share dominance of the largest distributors has increased over time, rather than decreased. Whereas the top 10 wine and spirits distributors combined for 59 percent of the market share in 2010, they comprised 75 percent of market share just 10 years later in 2020.[41] Therefore, when analyzing trends to measure whether a particular market has become “more concentrated” over time, as suggested by the administration’s guidance, it is clear that the wholesaler tier of alcohol markets would be the most likely sector of the alcohol industry to fall under this definition.

The prevailing legal structure governing the alcohol industry works to exacerbate this market concentration and consolidation in the distributor tier. For instance, laws granting wholesalers “exclusive territories” over certain sales regions in states essentially grants wholesalers a government-mandated middleman role that inevitably serves to entrench their market dominance.

Franchise laws that make it difficult for producers to terminate contracts with wholesalers also lock-in entrenched power structures and can lead to market dominance. Finally, laws forbidding—or greatly limiting—the ability of alcohol producers to self-distribute directly to retailers or to engage in interstate direct-to-consumer shipments, prevent a market-oriented response that could alleviate wholesaler consolidation and concentration concerns.

These legal structures inevitably lead to situations where alcohol producers become beholden to the decisions of their wholesaler partners. For instance, franchise laws are designed to lay out what constitutes “good cause” for an alcohol producer to be able to terminate its contract with a wholesaler. The stringent definition of good cause in many state codes often makes it legally impossible to end the contractual relationship for legitimate businesses reasons such as flagging sales or inadequate performance by the wholesaler.[42] As a result, stories abound of producers being locked into contracts with wholesalers and having to withdraw their products entirely from a geographical region if they are unsatisfied with the wholesaler.[43] It is therefore not an exaggeration to say that market access in many locales can live or die with the decisions and conduct of a single wholesaler.

This problem can be even more pronounced in control states in which the government is in charge of the wholesale and/or retail tier for alcohol. Currently, in 17 states the government controls all wholesale and/or retail sales of distilled spirits.[44] When a single entity is in control of all the wholesale or retail sales of a product, that entity gets to determine which products are granted access to the marketplace.

For example, in Ohio, the state is the exclusive wholesaler and warehouser for all spirits sold in the state. As a result, gin bars in the state are restricted to selling only the 96 brands of gin offered by the state, compared to gin bars in other parts of the country and world that can stock thousands of gins.[45] In other control states, distillers have been rejected from having their spirits carried in the state-controlled retail stores, which locks them out of their home state market entirely.[46] Questions also need to be asked about how products are picked for state store specials and samplings.

Under the long-recognized judicial principle of the “state-action doctrine,” governmental entities have traditionally been exempted from antitrust scrutiny. However, it is also clear that control states are a unique legal relic under U.S. law given that the state is an active market participant and a self-interested economic actor within the alcohol marketplace. Control states make money for the state government coffers through voluminous sales of alcohol products by participating in the wholesale tier as well as the retail tier. As market participants, control states have generated millions, and even billions, of dollars running the government alcohol enterprise. For example, according to the National Alcohol Beverage Control Association (NABCA): “From 2008 through 2018, the Iowa Alcoholic Beverages Division contributed close to $1.3 billion to state and local treasuries.”[47]

The “state-action doctrine” should not be simply accepted as an absolute in any state without asking and answering probing questions. For example, is there a clearly stated policy for government actions to displace naturally occurring marketplace competition? If there is one, how is it monitored and audited to determine whether state actions taken actually ensure fair competition within the alcohol beverage industry? Further, when state agencies are market participants, as well as market regulators in these same markets, then what standards should apply?

In comparison to, say, the environmental sphere, where governments act in a more traditional governance and regulatory role, alcohol control states feature wholesale and retail operations that operate like private entities, sell private commercial products and generate substantial revenue. Significantly, the Supreme Court has shown more willingness in recent years to narrow the breadth of state-action antitrust immunity in situations when entities cloaked with governmental authority also include active market participants.[48]

In summation, concerns over market concentration in the alcohol industry most naturally attach to the wholesale tier. The market share dominance of large wholesale firms has substantially increased in recent years and, unlike the producer-level, there has been no explosion in new market entrants to help diversify the market and lead to greater fragmentation. The producer-level emphasis on localism is also not applicable at the wholesale tier, taking away another natural restraint on national firms being able to dominate in the wholesale sector.

Given these trends toward greater wholesaler consolidation—and the long-standing legal structures that entrench wholesaler power within the alcohol marketplace—it is worth considering what policy responses, if any, should be adopted. Some commentators have suggested that even though the TTB may not be able to “directly hit the consolidation issue,” it “could issue regulations that favor small [industry stakeholders] over big [industry stakeholders].”[49]

Even if the TTB were inclined to exercise its authority in such a fashion, it is important to recognize the fact that most alcohol regulation resides at the sub-national level, which suggests that state governments may be best positioned to respond. Of the available policy levers, renewed state-level efforts to expand self-distribution rights for alcohol producers could provide the most promising solution to allow producers to avoid becoming beholden to consolidated wholesalers. Expanding direct-to-consumer (DtC) shipment options for producers also provides another vehicle for expanding market access for producers.

These reforms, coupled with overhauling outdated legal vestiges like franchise laws and exclusive territories, would ensure an infusion of market-oriented forces into the alcohol industry in a way that expands market access and counteracts distributor-level consolidation.

Retail-Level Concentration

Analyzing concentration in alcohol retailing markets is a notoriously difficult undertaking given the incredibly diverse and differentiated ways in which alcohol is sold in America. Entities ranging from grocery stores to baseball stadiums sell alcohol. Even within those categories, there is intense diversity and range. For example, grocery stores are notably regional in flavor, with no one grocery store chain being present in all 50 states.[50]

As one analysis put it when summarizing the alcohol retailing industry (which it classified as companies selling “beer, wine, and liquor products from physical retail establishments”): “No major companies dominate; in the US, individual states have different laws regulating liquor stores, complicating the ability to form national chains.”[51] The report found there were 33,000 alcohol retail establishments in America and concluded: “The US industry is highly fragmented: the top 50 companies account for about 25% of sales.”[52]

Importantly, the retail sector for alcohol also features a key bifurcation between on-premise retail and off-premise retail. On-premise alcohol sales account for up to 45 percent of total alcohol sales, underscoring the significant role it plays in the marketplace.[53] Most of these sales take place within the restaurant sector, an industry known for its extreme fragmentation.[54] Also, producers are increasingly growing their on-premise sales via taprooms and tasting rooms, providing yet another retail channel.

A final form of market fragmentation in alcohol retailing is taking place right before our eyes. COVID-19 ushered in a wave of state-level reforms that made it legal for many alcohol producers and retailers to sell and deliver their products directly to consumers.[55] To-go cocktails spread to a significant number of states—many of which have now made those reforms permanent—and more states permitted off-premise alcohol delivery from groceries and other retail outlets.[56] Finally, several states allowed DtC alcohol shipping, both intrastate and interstate, during the pandemic.[57] These new sales channels will only increase market access for producers and further differentiate the alcohol retailing market in the years ahead.

Given these trends, caution from federal government regulators once again is warranted when it comes to the alcohol-retailing tier.

Other Restrictions on Competition in the Alcohol Industry

As noted, the administration’s EO generally directed consideration to “any threats to competition and barriers to new entrants,” including “regulations pertaining to such things as bottle sizes, permitting, or labeling that may unnecessarily inhibit competition.”[58]

There are many potential “threats to competition” and “barriers to new entrants” when it comes to alcohol rules and regulations, but one specific focus should be a reconsideration and revamp of the TTB’s product labeling rules. Under current rules, labels for wine, beer and distilled spirits are subject to a host of restrictions on what can and cannot be included.

Some of these rules are understandably designed to prevent false or misleading statements that could harm consumers, but others are less defensible. For instance, alcohol labels are prohibited from including “health-related statements,” which include not only specific health claims but also “general references to alleged health benefits or effects on health associated with the consumption of alcohol” as well as “statements and claims that imply that a physical or psychological sensation results from consuming” an alcoholic product.[59]

These rules, written broadly as they are, are ripe for over-enforcement, which in fact is exactly what has happened. To date, the TTB has rejected a near-comical list of beer labels under the guise they were advancing health-related claims: King of Hearts (a playing card with a heart was deemed to imply the beer provided a health benefit); St. Paula’s Liquid Wisdom (granting “wisdom” was deemed a medical claim); Pickled Santa (purportedly because an image of Santa’s eyes on the label were “too googly”); and Bad Elf (a warning that elves not operate toy-making machinery while drinking the beer was deemed to be too confusing to consumers).[60]

In addition, words like “elixir,” “pure,” “vintage” and “alchemy” have also ran afoul of the TTB’s labeling rules in the past.[61] Needless to say—although, apparently, it does need to be said—the idea that a beer called King of Hearts was seriously advancing a health claim or that St. Paula’s Liquid Wisdom was trying to convince customers it would make them “wise” is both inaccurate and detached from reality. The agency should look to tighten and clarify its definition of what constitutes a “health-related claim” in a way that is more narrowly tailored to its objectives and does not ensnare innocuous and harmless alcohol labels in the process.

TTB rules also prohibit alcoholic beverage labels from including “[a]ny statement, design, device, or representation which is obscene or indecent.”[62] In contrast to the over-enforcement of health claims, enforcement of this provision of TTB regulations largely appears to have been abandoned in recent years.[63] As two examples, beers named “Little Fuck” and “Fuck Trump and His Stupid Fucking Wall” were approved in the last few years.[64] Perhaps most incredibly of all, in an act of seeming regulatory dissonance, a beer named “Fuck Art Let’s Dance” was rejected—although not for obscenity but rather because it included a random picture of a hamburger on the label, which was deemed to imply that a meat additive had been added to the beer.[65]

In the wake of recent Supreme Court litigation on obscene words in patents, TTB retrenchment from vigorous enforcement of its obscenity labeling rules is likely wise (even wiser than St. Paula’s Liquid Wisdom) given the high probability that they are unconstitutional.[66] Nevertheless, the regulations persist. Reforming them—or, better yet, eliminating them entirely—is a long-overdue step that should be prioritized. It should also be noted that some states echo TTB labeling rules against obscenity, and states have proven more willing to enforce these prohibitions (although several of these actions have been challenged successfully in judicial proceedings).[67] The TTB could therefore act as a policy leader in this realm by overhauling its obscenity rules, which could in turn encourage state governments to follow suit.

TTB rules also prohibit any “false or untrue” statement or a statement that, “irrespective of falsity (…) tends to create a misleading impression.”[68] Again, efforts to prevent false advertising are important, but overenforcement of these standards have led to head-scratching situations like an “India Dark Ale” being rejected because it might mislead a consumer into thinking the beer was made in India—despite the common prevalence of India Pale Ales, as well as the fact that the beer label specifically noted it was a product of Denmark.[69] Another credulity-stretching instance involved a brewery in Washington, D.C. that had a label rejected because it listed the brewery’s location as “District of Columbia,” in contrast to its brewers license, which said “Washington, D.C.”[70]

Although commentators have suggested that TTB enforcement of its labeling rules has relaxed in recent years, it is important once again to recognize that the regulations still exist. Changes in staff or leadership can occur over time, and it is therefore possible that these onerous labeling rules could be more vigorously enforced again in the future.

These TTB labeling rules unquestionably act as a threat to competition and barrier to new entrants, as the costs fall disproportionately on smaller producers that do not have robust legal compliance teams, nor the resources available to revise labels constantly should they be unexpectedly rejected. As one craft brewer put it: “[E]very tweak or edit that we have to make [to a label] is a definite monetary cost to us.”[71] Unsurprisingly, larger firms are better able to absorb these costs, whereas smaller producers are forced to redirect time and money away from making their products and toward overburdensome compliance efforts.

Updating and streamlining federal labeling requirements is a readily available reform that the TTB could engage in that would help encourage competition and reduce costs for smaller-scale producers.

Sincerely,

Jarrett Dieterle[72]

Teri Quimby[73]

[1] “Executive Order on Promoting Competition in the American Economy,” The White House, July 9, 2021, Sec. 5(j)-(k). https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2021/07/09/executive-order-on-promoting-competition-in-the-american-economy/.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] C. Jarrett Dieterle and Teri Quimby, “Coming to a Door Near You: Alcohol Delivery in the COVID-19 New Normal,” R Street Policy Study No. 215, November 2020, pp. 3-5. https://www.rstreet.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Corrected-Final-RSTREET215.pdf.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] “Klobuchar Renews Call to Protect Competition in the Beer Market,” June 22, 2016. https://www.klobuchar.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/2016/6/klobuchar-renews-call-to-protect-competition-in-the-beer-market; Mike Pomranz, “Democrats Court Beer Geeks by Going After ‘Big Beer’ Monopolies,” Food & Wine, May 14, 2019. https://www.foodandwine.com/news/democrats-big-beer-monopolies.

[8] Heather Boushey and Helen Knudsen, “The Importance of Competition for the American Economy,” The White House, July 9, 2021. https://www.whitehouse.gov/cea/blog/2021/07/09/the-importance-of-competition-for-the-american-economy/; Office of Public Affairs, “Justice Department Requires Anhesuer-Busch InBev to Divest Stake in MillerCoors and Alter Beer Distributor Practices as Part of SAB Miller Acquisition,” The United States Department of Justice, July 20, 2016. https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-department-requires-anheuser-busch-inbev-divest-stake-millercoors-and-alter-beer.

[9] Rajat Sharma, “More Consolidation For Alcoholic Beverage Companies,” Seeking Alpha, May 13, 2014. https://seekingalpha.com/article/2215143-more-consolidation-for-alcoholic-beverages-companies;

“Insight: Most prospective global alcohol beverage markets,” Ambrosia Magazine, July 8, 2021. https://www.fhafnb.com/most-prospective-global-alcoholic-beverage-markets/; Jeremy Lott, “A Sober Look at the Dangers of Craft Beer Consolidation,” The American Conservative, March 23, 2020. https://www.theamericanconservative.com/articles/a-sober-look-at-the-dangers-of-craft-beer-consolidation/.

[10] Jeremy Lott, “A Sober Look at the Dangers of Craft Beer Consolidation,” 2020. https://www.theamericanconservative.com/articles/a-sober-look-at-the-dangers-of-craft-beer-consolidation/.

[11] Kate Bernot, “We Had a Good Thing Going—Distributor’s Challenge to Massachusetts Franchise Reform Could Unravel Decades of Negotiations, Good Beer Hunting, March 19, 2021. https://www.goodbeerhunting.com/sightlines/2021/3/19/massachusetts-franchise-reform-could-unravel-after-decades-of-negotiation; John Liberty, “Bell’s Brewery Inc.’s lawsuit against distributor may spotlight Michigan’s three-tier system debate, Big beer vs. craft beer,” MLive, April 4, 2019. https://www.mlive.com/kalamabrew/2009/05/bells_brewery_inc_files_lawsui.html.

[12] Marc E. Sorini, “Beer Franchise Law Summary,” Brewers Association, last accessed Aug. 11, 2021. https://www.brewersassociation.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Beer-Franchise-Law-Summary.pdf.

[13] C. Jarrett Dieterle, “North Carolina’s Beer Pong Battle,” The American Conservative, April 17, 2017. https://www.theamericanconservative.com/articles/north-carolinas-beer-pong-battle/.

[14] Heather Boushey and Helen Knudsen, “The Importance of Competition for the American Economy,” The White House, FN 1-3. https://www.whitehouse.gov/cea/blog/2021/07/09/the-importance-of-competition-for-the-american-economy/.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid. at FN 4.

[17] “Executive Order on Promoting Competition in the American Economy,” 2021, Sec. (5)(j)(ii). https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2021/07/09/executive-order-on-promoting-competition-in-the-american-economy/.

[18] “Fact Sheet: Executive Order on Promoting Competition in the American Economy,” The White House, July 9, 2021. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/07/09/fact-sheet-executive-order-on-promoting-competition-in-the-american-economy/.

[19] “Industry Fast Facts: The U.S. Beer Industry 2020,” National Beer Wholesalers Association, last accessed Aug. 11, 2001. https://www.nbwa.org/resources/industry-fast-facts.

[20] Brian Wallheimer, “Why craft beer’s rise is a warning flag for all sorts of big brands,” Chicago Booth Review, June 28, 2021. https://review.chicagobooth.edu/marketing/2021/article/why-craft-beer-s-rise-warning-flag-all-sorts-big-brands.

[21] “Brewers Association Releases Annual Growth Report for 2019,” Brewers Association, April 14, 2020. https://www.brewersassociation.org/press-releases/brewers-association-releases-annual-growth-report-for-2019/.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Chris Morris, “Despite Zoom happy hours and day drinking, 2020 wasn’t a great year for craft brewers,” Fortune, April 6, 2021. https://fortune.com/2021/04/06/craft-brewers-2020-sales-market-share-closings-beer-independent-brewers-association/.

[24] “National Beer Sales & Production Data,” Brewers Association. https://www.brewersassociation.org/statistics-and-data/national-beer-stats/.

[25] “Annual Craft Spirits Economic Briefing,” American Craft Spirits Association, October 2019. https://americancraftspirits.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/2019_Craft-Spirits-Data-Project_101819-v5-compressed.pdf.

[26] Renée Johnson and Sean Lowry, “Craft Alcoholic Beverage Industry: Overview and Regulation,” Congressional Research Service, Jan. 7, 2021. https://www.everycrsreport.com/files/2021-01-07_IF10973_fa13b154b4b9384085e9a79aa0548dc810e2cdd7.pdf; Andrew Adams, “The Challenge of Distributor Consolidation,” Wine Vines Analytics, September 2017. https://winesvinesanalytics.com/features/article/189049/The-Challenge-of-Distributor-Consolidation.

[27] Ranjit S. Dighe, “The Craft Beer Explosion: Why Here? Why Now?”, Process History, July 6, 2017. http://www.processhistory.org/craft-beer-dighe/; Caleb Houseknecht, “How Jimmy Carter Sparked the Craft Beer Revolution,” KegWorks, Jan. 29, 2013. https://content.kegworks.com/blog/how-jimmy-carter-sparked-the-craft-beer-revolution.

[28] Brian Wallheimer, “Why craft beer’s rise is a warning flag for all sorts of big brands,” 2021.

[29] Christopher Holtkamp et al., “Assessing Neolocalism in Microbreweries,” Papers in Applied Geography, (March 2016) p. 66. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283578221_Assessing_Neolocalism_in_Microbreweries.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Ibid. at 68.

[33] Jarrett Hart, “Drink Beer for Science: An Experiment on Consumer Preferences for Local Craft Beer,” Journal of Wine Economics (Nov. 20, 2018). https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-wine-economics/article/drink-beer-for-science-an-experiment-on-consumer-preferences-for-local-craft-beer/77FBA0D7CE3B1D21FCE7E3BD5307E589.

[34] Bart J. Bronnenberg et al., “Millennials and the Take-Off of Craft Brands: Preference Formation in the U.S. Beer Industry,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series, No. 28618 (March 2021). https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w28618/w28618.pdf.

[35] Cat Wolinski, “Hop Take: Flagship Beers Are Failing Because Consumers Get Bored Quickly,” VinePair, Jan. 3, 2019. https://vinepair.com/articles/hop-take-flagship-beers-failing/; Matthew Thompson, “Rotation Nation: Getting the Most out of Draft Beer Rotation,” LinkedIn, Nov. 30, 2017.

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/rotation-nation-getting-most-out-draft-beer-matthew-thompson.

[36] Micheline Maynard, “The Craft Spirits Industry Is Taking Off as Drinkers Embrace Local Booze,” Forbes, July 20, 2018. https://www.forbes.com/sites/michelinemaynard/2018/07/20/the-craft-spirits-industry-is-taking-off-as-drinkers-embrace-local-booze/?sh=6a89d33b505e.

[37] Tenn. Wine & Spirits Retailers Ass’n v. Thomas, 588 U.S. ____, 139 S. Ct. 2449 (2019).

[38] Andrew Adams, “The Challenge of Distributor Consolidation,” 2017. https://winesvinesanalytics.com/features/article/189049/The-Challenge-of-Distributor-Consolidation.

[39] Mark Evans, “Winery Adaption,” Protea Financial, May 6, 2021. https://proteafinancial.com/winery-adaptation/.

[40] “Industry Fast Facts: The U.S. Beer Industry 2020,” National Beer Wholesalers Association. https://www.nbwa.org/resources/industry-fast-facts.

[41] Daniel Marsteller, “The RNDC-Young’s Deal Creates a New Landscape Within The Middle Tier,” Shanken News Daily, June 14, 2019. https://www.shankennewsdaily.com/index.php/2019/06/14/23247/the-rndc-youngs-deal-creates-a-new-landscape-within-the-middle-tier/.

[42] Daniel Croxall, “Independent Craft Breweries Struggle Under Distribution Laws that Create a Power Imbalance in Favor of Wholesalers,” William & Mary Business Law Review, 12:2 (February 2021). https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1211&context=wmblr.

[43] Keith Gribbins, “Bell’s Brewery pulls out of Virginia over distribution dispute,” Craft Brewing Business, Feb. 11, 2019. https://www.craftbrewingbusiness.com/featured/bells-brewery-pulls-out-of-virginia-over-distribution-dispute-we-discuss-it-with-larry-bell-other-distribution-news/.

[44] “Control State Directory and Info,” National Alcohol Beverage Control Association, last accessed Aug. 11, 2021. https://www.nabca.org/control-state-directory-and-info.

[45] C. Jarrett Dieterle, Give Me Liberty and Give Me a Drink!, (Artisan Books, 2020), pp. 86-87. https://www.workman.com/products/give-me-liberty-and-give-me-a-drink.

[46] The Right to Drink, Why Your Craft Cocktail Should Cost $4, R Street Institute Podcast, Sep. 15, 2020. https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/why-your-craft-cocktail-should-cost-$4/id1530460077?i=1000491312250.

[47] Control State Directory and Info: Iowa, National Alcohol Beverage Control Association, last accessed Aug. 11, 2021. https://www.nabca.org/sites/default/files/assets/files/IA%20one%20pager_Final.pdf.

[48] North Carolina State Board of Dental Examiners v. Federal Trade Commission, Slip Op. No. 13-534, Feb. 25, 2015. https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/14pdf/13-534_19m2.pdf.

[49] W. Blake Gray, “Biden to Take on Big Wine,” Wine-Searcher, July 20, 2021. https://www.wine-searcher.com/m/2021/07/biden-to-take-on-big-wine.

[50] Jeff Campbell, “Why Are Grocery Stores Regional?”, The Grocery Store Guy, last accessed Aug. 11, 2021. https://thegrocerystoreguy.com/why-are-grocery-stores-regional/.

[51] “First Research Industry Reports,” The Watson CPA Group, last accessed Aug. 11, 2021. https://wcginc.com/wp-content/documents/FirstResearch.pdf.

[52] Ibid.

[53] Tara Nurin, “Alcohol Sales Are Not Spiking Or Even Stabilizing. Here’s Why The Misconception Matters,” Forbes, June 30, 2020. https://www.forbes.com/sites/taranurin/2020/06/30/alcohol-sales-are-not-spiking-or-even-stabilizing-heres-why-this-misconception-matters/?sh=718ba7ca3c81.

[54] Michael S. Kaufman et al., “Restaurant Revolution: How The Industry Is Fighting To Stay Alive,” Forbes, Aug. 10, 2020. https://www.forbes.com/sites/hbsworkingknowledge/2020/08/10/restaurant-revolution-how-the-industry-is-fighting-to-stay-alive/?sh=2d9162f1ebfe.

[55] Jarrett Dieterle and Teri Quimby, “Coming to a Door Near You: Alcohol Delivery in the COVID-19 New Normal,” 2020. https://www.rstreet.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Corrected-Final-RSTREET215.pdf.

[56] Amelia Lucas, “To-go cocktails will stick around in at least 20 states after the pandemic,” CNBC, May 28, 2021. https://www.cnbc.com/2021/05/28/to-go-cocktails-will-stick-around-in-at-least-20-states-after-covid.html;

Beth McKibben, “Georgia Governor Signs a Bill Allowing Grocery Stores and Restaurants to Deliver Booze,” Eater: Atlanta, Aug. 3, 2020. https://atlanta.eater.com/2020/8/3/21353245/governor-brian-kemp-signs-georgia-alcohol-delivery-bill-home-delivery-beer-wine-liquor; H. Mac Gipson, “Here’s how Alabama’s new wine and liquor delivery laws will work,” AL.com, May 4, 2021. https://www.al.com/news/2021/05/heres-how-alabamas-new-wine-and-liquor-delivery-laws-will-work.html; Parker King, “Alcohol delivery now permitted in Mississippi, Action News 5, April 26, 2021. https://www.wmcactionnews5.com/2021/04/26/alcohol-deliveries-now-permitted-mississippi/; Becky Phelps, “New Iowa law allows for expanded home delivery of alcohol,” KCRG News, July 3, 2021. https://www.kcrg.com/2021/07/03/new-iowa-law-allows-expanded-home-delivery-alcohol/.

[57] “DTC Consumer Survey Media Briefing,” Distilled Spirits Council of the United States, July 15, 2021. https://www.distilledspirits.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/7.15.2021-DTC-Survey-Media-Briefing-.pdf; Alex Koral, “Kentucky to Begin Permitting DtC Shipping of Alcohol,” Sovos, Dec. 15, 2020. https://sovos.com/blog/ship/kentucky-to-begin-permitting-dtc-shipping-of-alcohol/.

[58] Executive Order on Promoting Competition in the American Economy, 2021, Sec. 5(j)-(k). https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2021/07/09/executive-order-on-promoting-competition-in-the-american-economy/.

[59] Code of Federal Regulations, Title 27, Chapter I, Subchapter A, Part 4, §4.39(h), Title 27, Chapter I, Subchapter A, Part 5, §5.42(b)(b), and Title 27, Chapter I, Subchapter A, Part 7, §7.54(e).

[60] Tim Mak, “Meet the Beer Bottle Dictator,” The Daily Beast, April 14, 2017. https://www.thedailybeast.com/meet-the-beer-bottle-dictator?ref=scroll; The Right to Drink, F*ck True We Where Swear On Our Brews, R Street Institute Podcast, Sep. 29, 2020. https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/f-ck-true-we-swear-on-our-brews/id1530460077?i=1000492939722.

[61] Scott Rosenbaum, “What the TTB won’t tell you,” Ah So Insights, April 26, 2021. https://www.ahsoinsights.com/p/what-the-ttb-wont-tell-you.

[62] Code of Federal Regulations, Title 27, Chapter I, Subchapter A, Part 4, §4.39(a)(3), Title 27, Chapter I, Subchapter A, Part 5, §5.42(a)(3), and Title 27, Chapter I, Subchapter A, Part 7, §7.54(a)(3).

[63] Scott Rosenbaum, “What The TTB Won’t Tell You,” 2021. https://www.ahsoinsights.com/p/what-the-ttb-wont-tell-you.

[64] Department of the Treasury, Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau, Application for and Certification/Exemption of Label/Bottle Approval, TTB ID 21078001000064, March 19, 2021. https://ttbonline.gov/colasonline/viewColaDetails.do?action=publicFormDisplay&ttbid=21078001000064; Department of the Treasury, Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau, Application for and Certification/Exemption of Label/Bottle Approval, TTB ID 203110010000644, Nov. 6, 2020. https://ttbonline.gov/colasonline/viewColaDetails.do?action=publicFormDisplay&ttbid=20311001000644.

[65] Tim Mak, “Meet the Beer Bottle Dictator,” 2017. https://www.thedailybeast.com/meet-the-beer-bottle-dictator?ref=scroll; “Fuck Art – Let’s Dance,” BeerAdvocate, last accessed Aug. 11, 2021. https://www.beeradvocate.com/beer/profile/24299/96857/.

[66] Tom Dietrich, “NSFW beer trademarks are coming—will the TTB stand aside?,” Craft Brewing Business, Jan. 5, 2016. https://www.craftbrewingbusiness.com/business-marketing/are-nsfw-beer-trademarks-legal/.

[67] Andy Sparhawk, “Flying Dog Wins Raging Bitch Label Lawsuit,” CraftBeer.com, March 12, 2015. https://www.craftbeer.com/editors-picks/flying-dog-brewery-wins-raging-bitch-label-lawsuit; Paige Jones, “Flying Dog creates First Amendment nonprofit with lawsuit money,” The Frederick News-Post, May 23, 2016. https://www.fredericknewspost.com/news/economy_and_business/flying-dog-creates-first-amendment-nonprofit-with-lawsuit-money/article_18109cb1-61d4-501d-8e1a-3f6e9ef6401a.html; Robert C. Lehrman, “Good Beer No Shi*,” Lehrman Beverage Law Blog, July 8, 2019. https://bevlaw.com/bevlog/good-beer-no-shi/; Paul Woolverton, “NC alcohol regulators say ‘heck no’ to use of profane word on label of craft brew seltzer,” The Fayetteville Observer, March 10, 2021. https://www.fayobserver.com/story/news/2021/03/10/nc-brewer-fighting-regulators-put-f-word-its-craft-seltzer-label/6931319002/.

[68] Code of Federal Regulations, Title 27, Chapter I, Subchapter A, Part 4, §4.39(a)(1), Title 27, Chapter I, Subchapter A, Part 5, §5.42(a)(1), and Title 27, Chapter I, Subchapter A, Part 7, §7.54(a)(1).

[69] Tim Mak, “Meet the Beer Bottle Dictator,” 2017. https://www.thedailybeast.com/meet-the-beer-bottle-dictator?ref=scroll.

[70] The Right to Drink, F*ck True We Where Swear On Our Brews, R Street Institute Podcast, Sept. 29, 2020. https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/f-ck-true-we-swear-on-our-brews/id1530460077?i=1000492939722.

[71] Ibid.

[72] Jarrett Dieterle is a resident senior fellow at the R Street Institute, a nonpartisan public policy research organization located in Washington, D.C. R Street is the only national think tank with a dedicated alcohol policy research team that studies and analyzes the laws and regulations governing alcohol in the United States. R Street favors rational alcoholic beverage policies that respect individual freedom, free enterprise and the public well-being.

[73] Teri Quimby, JD, LLM, is an attorney, author and consultant. Quimby served as a member of the Michigan Liquor Control Commission from 2011-2019. She utilizes her LLM in corporate law and many years working on legislation and regulations in highly regulated sectors to encourage dialogue on public policy issues and to advise organizations on governance and compliance.