Yes, Mr. President, you need to stop importing Russian oil

There is currently a significant debate between the administration and a bipartisan cohort of representatives and senators from Congress on the issue of whether the United States should ban importation of Russian oil and petroleum products. The logic is pretty simple; Congress wants to show action in support of Ukraine, and the administration is worried that anything that forces gas prices—and inflation—even higher will hurt them in the midterms and threaten their agenda leading up to the 2024 elections. Mercifully, the policy solution here is also pretty simple: Russian imports are not significant enough for an import ban to be a decisive factor in energy prices, and the United States needs to set the example that it is serious about its sanction regime against Russia and preserving the norms of international sovereignty.

U.S. Energy Trade with Russia

Aside from rare instances, the United States essentially imports no natural gas from Russia, so for this topic, we will focus on oil and petroleum imports. The United States is the world’s largest producer of oil and petroleum products, and in December 2021, it was producing 17.3 million barrels per day. For comparison, Russia produces about 10.5 million barrels per day. Unlike Russia, though, the United States is a major consumer of oil and petroleum products. Despite the United States’ significant domestic supply and production, it oscillates between being a net-importer and net-exporter of oil and petroleum products, and up until recent years used to be a major importer of crude oil and petroleum products.

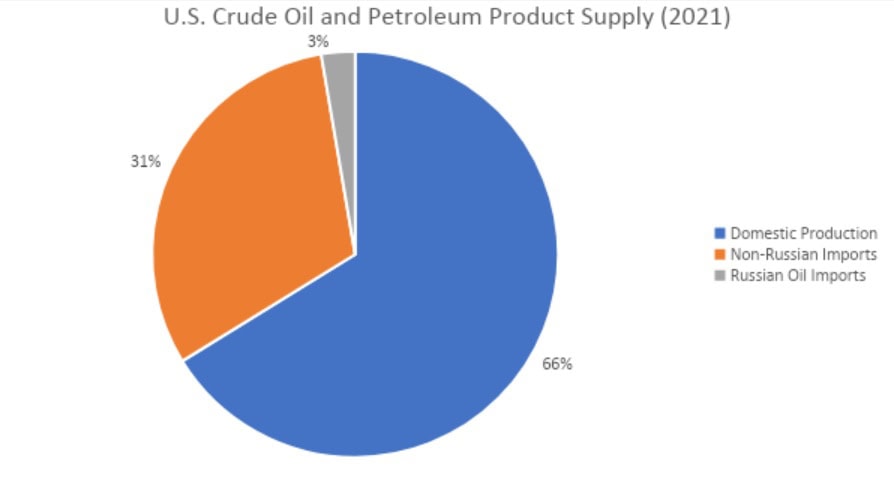

In terms of total crude oil and petroleum product supply in the United States, Russia is a minor player. In 2021, the United States produced 6.5 billion barrels of oil and petroleum products and imported 3.1 billion barrels; Russian imports accounted for 245 million barrels of imported product, or about 3 percent of total supply.

Source: EIA Oil & Petroleum Product data.

The administration fears that banning that 3 percent of oil and petroleum product import would have a negative effect on gasoline prices, which are already the highest seen since 2014. Constraining supply is sure to have a negative impact on prices, but the outstanding question is how much supply could be expected to increase to keep prices in check. Oil is a notoriously tight market for supply and demand, with even relatively minor swings in global production having big impacts on gasoline prices.

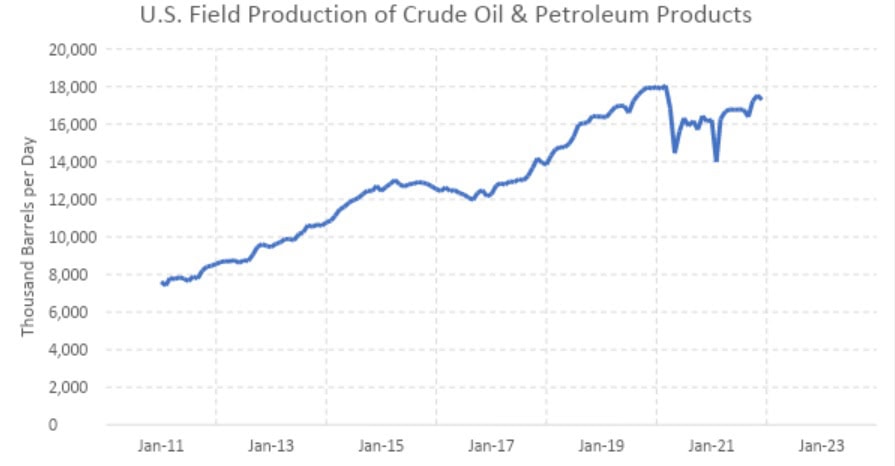

In the case of Russian imports, it should be noted that U.S. production is well below its pre-pandemic peak, by about 794,000 barrels per day.

Source: EIA Crude Oil Production data.

If the United States returned to pre-pandemic levels of production, it would increase its oil and petroleum product by about 286 million barrels per year, which would exceed the volume of losses from Russian imports. Domestic oil production can fill a breach caused by an embargo on Russian imports, and this would temper any increase in gasoline prices.

Even if the United States does not increase domestic production, foreign suppliers can fill this breach. Simply, the reason Russian oil and petroleum products are bought at all is because they are offered at the best price to the consumers in the United States. Alternative suppliers may be more expensive, but they are able to fill these gaps. Impacts on pump prices would reflect the difference in cost between Russia and the next-least-expensive supplier, rather than the price impact that accompanies supply shortages seen in the past.

Simply, a ban on Russian energy imports would be bad for gasoline pump prices, but it may not be as bad as the administration expects because rising prices would incentivize increased domestic production.

Value of Russian Energy Imports

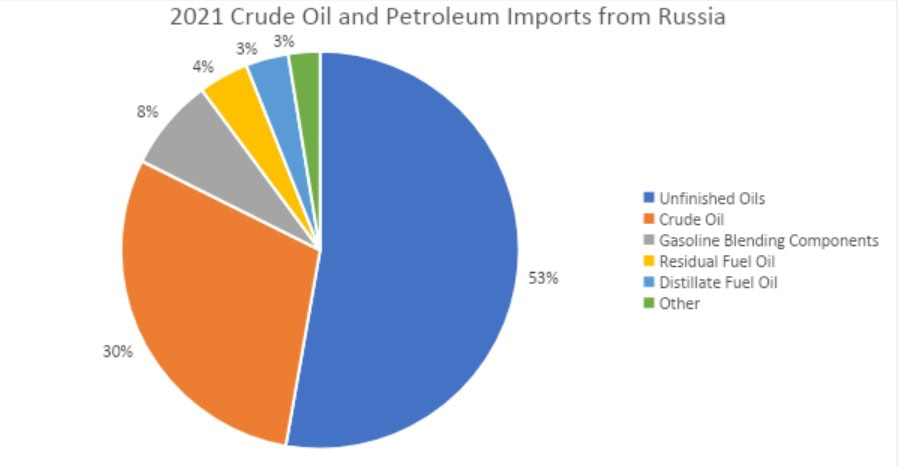

An outstanding question, though, is would an embargo against Russian energy imports seriously impact Russia as a sanction effort? Ascertaining the total value of Russian energy imports can be complicated because most of these imports are not crude oil, where pricing is readily available. Of the 245 million barrels of oil and petroleum product imported from Russia in 2021, 53 percent were unfinished oils (partially refined crude oil), 30 percent were crude oil, 7 percent were gasoline blending components, and the remaining 10 percent were other residual and distillate fuels.

Source: EIA data on crude oil and products imports (Russia).

It is difficult to know the exact value of these imports, as data usually lags a few months, but most of Russian energy imports are related to gasoline production—unfinished oils are usually naphtha, which is further refined into liquid fuels. As such, it is fair to assign current crude oil prices as a rough corollary for the value of these imports. One should note, though, that a barrel of crude oil produces more than a barrel of finished petroleum product because refined product is less dense than crude oil.

Using 2021 as a corollary, the United States imports about 672,000 barrels of Russian crude oil and petroleum product per day. The current spot price for oil in the United States (West Texas Intermediate) is $118 per barrel. This would indicate that Russian energy imports are worth about $79.3 million per day. The true value may be lower or higher than this, but this could be considered a ballpark estimate.

One should note that crude oil prices have risen 28 percent since the beginning of the year. The expected current value of imports from Russia are exceptionally high compared to historical data.

An embargo against Russian energy imports, though, is unlikely to make a huge difference to Russia. The United States only accounts for approximately 1 percent of its crude oil exports. China is Russia’s largest oil customer at 31 percent of its exports, and all of the developed nations combined in Europe buy about 48 percent of Russia’s oil exports. A U.S. ban on Russian energy imports is unlikely to turn the tide on Russia’s war effort.

But it’s not really about oil

The potential importance of the United States ending energy imports from Russia, though, has less to do with oil prices and more to do with amping up the effectiveness of sanctions. A previous R Street blog post noted that the impact of major sanctions against Russia are severely dampened by the exemptions carved out for energy trade. Oil is traded in U.S. dollars, but Russia’s budget is set in its local currency of rubles. As the ruble falls, the relative value of its oil exports—which directly fund its budget through state-owned enterprises—becomes a stronger lifeline to sustain its war effort against Ukraine.

The United States can’t honestly claim to be taking a firm hand against Russia while simultaneously giving it a steady supply of foreign currency through its energy trade, which directly undermines the impact of the Western sanction regime against Russia. A weak ruble means little if Vladimir Putin is being sent foreign currency through his unimpeded energy trade with the West. U.S.-Russia energy trade is not big enough to force Putin to relent against Ukraine, but it is an important symbolic retaliation.

If the United States does not embargo Russian energy imports, the message it is sending is, “we care about national sovereignty and world peace—but only if it doesn’t affect gasoline prices.” U.S. credibility is on the line; the administration must show the world that it is willing to do what is right—and, in this case, the cost can be tempered by increased domestic production.

Conclusion

The United States does not rely on Russian energy imports. If U.S. energy production returned to pre-pandemic levels, it would overcome any loss of imported supply from Russia. As long as the United States refuses to ban Russian energy imports, it shows the world that gasoline prices remain the soft underbelly that lets far weaker countries bully the United States. There are very few times where there is a clearly correct foreign policy decision vis-à-vis an adversarial regime, but this is one of those times. Mr. President, it is time to end Russian energy imports.