We Should Reevaluate the Costs and Benefits of the Renewable Fuel Standard

Since 2005, the United States has had a program mandating the blending of biofuel into the nation’s fuel supply. Known as the Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS), the logic of the program was that it would reduce our reliance on foreign oil supplies, which was considerable at the time and had uncertain reliability given conflicts in the Middle East. The program later expanded to include a greenhouse gas emission abatement component, giving it a dual purpose of energy security and climate program. But there has been a perennial and mostly unanswered question about the RFS: What does it really cost Americans? Proponents contend that it bears little cost, while critics believe the cost is high. Recent R Street research offers additional insight and reinforces conventional economic theories about the program’s shortcomings.

From a basic economics perspective, we know that if the government mandates that a product must be consumed, the cost of that product will rise because the governmental policy has increased the demand for it. Captive customers must then pay a higher price, though how much more they pay depends on how much the policy increases price and how much more of a product is consumed because of it. More simply, while a government mandate to purchase something always entails an economic cost, the magnitude of that cost depends on how proximate the mandate is to what would have occurred in the market absent the mandate.

The RFS currently requires that 22.33 billion gallons of renewable fuel be blended into the domestic supply, with 7.33 billion gallons of “advanced” biofuel (produced from cellulose and inedible plant matter instead of food) leaving 15 billion gallons per year of conventional biofuel (mostly from corn-based ethanol). For context, the United States consumes 376 million gallons of finished motor gasoline per day, or 137 billion gallons per year. The conventional portion of the RFS thus accounts for a little over a tenth of the domestic liquid fuel supply, and drivers are likely familiar with pump labels that claim the fuel “contains 10% ethanol.” About 40 percent of corn grown in the United States is used to produce ethanol for the RFS. Thus, the program supports a very large liquid fuel and domestic farming industry—but how much does this cost?

Earlier estimates assumed the RFS would cost little because, returning to our earlier point, it was assumed that its blending obligations would be similar to what market demand would be even without the program. Biofuels were relatively cheap at the time of the RFS’ inception, while imported foreign oil was very expensive. Ethanol also has a higher octane rating than gasoline, so refiners often use it as a cost-effective means to increase octane. The blend rate of ethanol in gasoline was around 4 percent back in 2005, so the idea that refiners would already demand a lot more biofuel even without the RFS made a fair bit of sense.

But while analysts and projections may not be wrong right away, they always are when given enough time. Oil prices have collapsed three times since the RFS’ inception, and domestic oil production has nearly tripled. Overall fuel consumption has remained flat rather than increasing, owing to greater fuel efficiency of cars and other factors (e.g., a global pandemic and remote work). The market advantage of ethanol and other biofuels is lessened under these sorts of conditions; however, the requirements of the RFS did not go away, and the program has likely induced a considerable cost to fuel consumers.

At R Street, we analyzed this additional cost for the conventional biofuel portion of the RFS. First, we developed a baseline estimate of how much ethanol would be consumed absent the RFS. To do this, we first looked to another region with high fuel prices: Europe, where the typical blend rate of ethanol to gasoline is 5 percent. We use this as a minimum expectation of ethanol blending that would occur absent a requirement. We then examined the cost of ethanol in terms of energy content (ethanol is less energy dense than gasoline, so it reduces the fuel efficiency of vehicles), and compared it to gasoline. Finally, we assume that the additional consumption of ethanol above our baseline is attributable to the RFS. The result is that, over a 10-year period (2014-2023), Americans spent $28 billion more on ethanol than the same amount of energy from gasoline would have cost.

The increased cost from the RFS forcing Americans to buy a more expensive form of energy is only one portion of the program’s cost—it also includes a compliance mechanism revolving around “Renewable Identification Numbers” (RINs). For every gallon of biofuel produced, a RIN is also produced. At the end of the year, refiners with obligations to blend ethanol use RINs to track how much biofuel is consumed. In cases where refiners are unable to meet these obligations, they may purchase RINs from other producers.

Not all refiners must purchase RINs; however, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency notes that even in cases where no RIN purchases are made (e.g., where an integrated refiner can both produce their own biofuel and blend it into finished gasoline), the implicit value of the RIN is still present. For example, if there is a blend obligation of 15 billion gallons and RINs cost $1 each, even if only a small fraction of refiners had to purchase RINs, the value of the RINs is still present for other refiners who can choose to sell RINs or would otherwise have to purchase them. More simply, whether or not a refiner purchases a RIN, the pump price reflects the implicit value of the RIN that either was bought or had the potential to be bought.

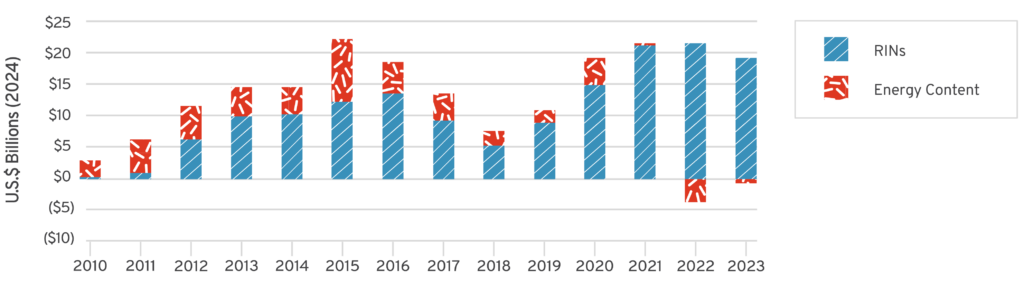

RIN prices have fallen in recent years, although they had been exceptionally high not long ago. In 2010, RIN prices for conventional biofuel were only a few cents per gallon; in 2023, they peaked at over $1.50 per gallon. More recently, prices have been between $0.50 and $0.75 per gallon. Higher RIN prices reflect RFS compliance challenges—if gasoline consumption is low, then there is less opportunity for biofuel blending, and obligated parties pay a premium to comply with the program (which is passed on to consumers). Overall, we estimate that the cost of compliance with the RFS, reflected in RIN prices, was $138 billion from 2014 to 2023. Essentially, the RFS cost approximately $164 billion over a 10-year period, as illustrated in the following chart.

Whether that cost is worth bearing, though, depends largely on what Americans feel they are getting out of the RFS. It is worth noting that the energy security arguments have largely lessened since the RFS’ inception. Domestic biofuels are no longer competing with foreign oil producers, but with domestic oil producers. While energy security is a more complex issue than just foreign versus domestic production, the security of domestic oil production and the ability to supply demand readily has grown considerably since 2005.

The justification for the RFS as an environmental program has also weakened. The emission benefits of the RFS are debatable, as studies have a hard time agreeing upon how much emission abatement ethanol can yield when supplanting gasoline. But the cost-effectiveness of a program is not just in what effect the program has, but also in what it costs. Because the economics of fuel production have changed considerably over the past two decades, the RFS simply costs too much to produce an emission benefit comparable to the value of avoided climate damages. Our analysis utilized the most optimistic estimates of ethanol’s emission abatement potential from Argonne National Laboratory, finding an average abatement cost of $1,464 per metric ton of carbon dioxide (CO2) avoided—far above the estimated value of the social benefit per ton of CO2 avoided.

The earlier question of whether the RFS costs a lot or a little is subjective, but that may not be what is important. Truthfully, there is no reasonable economic justification for the RFS. If advocates of the program were correct that it costs little since refiners would demand similar quantities of biofuel anyway, then it would mean the program delivers no benefit and should be repealed so that the market—rather than bureaucrats—can determine the optimal level of blending biofuel into domestic fuels.

Alternatively, if the RFS has driven an excessive consumption of ethanol and other biofuels, then it would have a considerable cost and should be repealed because its energy security and environmental benefits—even decades after implementation—cannot be reasonably demonstrated. The RFS gives too little benefit on either front to be good policy.

While the economic view of a program like the RFS is that the government should not engage in such mandates in the first place, even if the program is not repealed policymakers ought to commission further evaluation to scrutinize its effectiveness and guide future actions.