The United States is at a Tipping Point on Juvenile Life Without Parole

The U.S. juvenile justice system recently crossed a major milestone, which went largely unnoticed. On Feb. 7, 2023, Illinois became the 26th state to ban juvenile life without parole. Now that more than half of U.S. states have taken this important step, we may be at the tipping point necessary to end this cruel and unusual practice once and for all.

This policy shift has been a victory for conservatism. Permanently locking up children is incompatible with the values of limited government, fiscal responsibility, and the right to life and liberty. On the Illinois Senate floor, Sen. Donald DeWitte spoke forcefully in favor of the bill. “I consider myself a law-and-order Republican, but I also believe in rehabilitation. I believe there are some people who make extremely poor decisions in the very early portions of their lives,” he said. “For these people, we need to offer them hope and let them know we recognize that people can redeem themselves.”

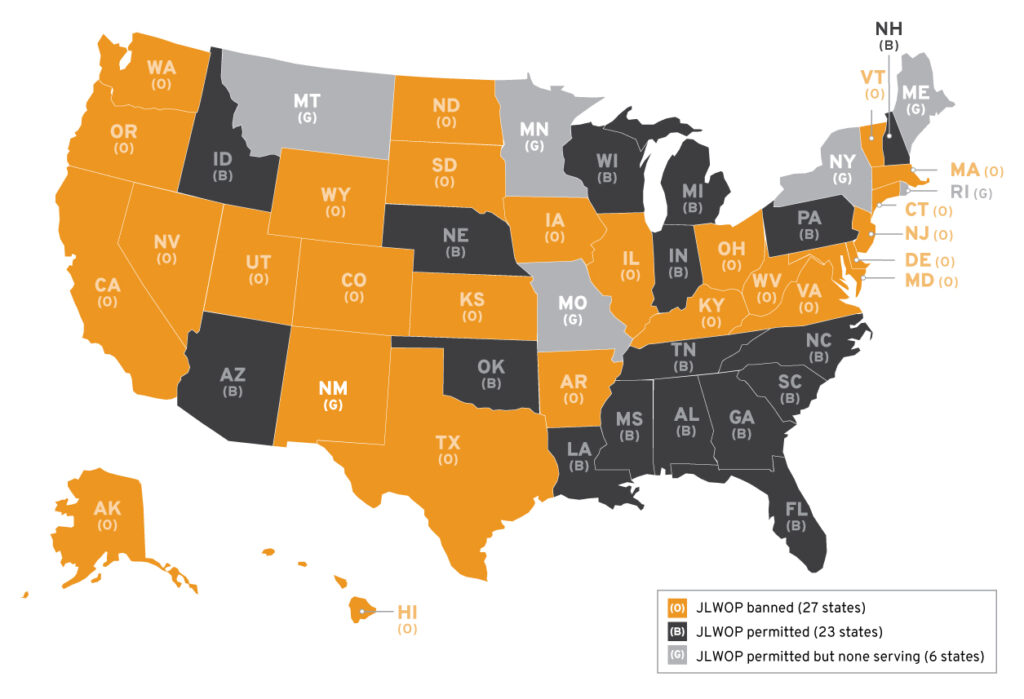

Which states ban juvenile life without parole?

Twenty-seven U.S. states have now banned juvenile life without parole. In total, 33 states and D.C. have banned or currently have no one serving life without parole for a crime committed under the age of 18. Data Source: The Campaign for the Fair Sentencing of Youth

Juvenile Life Without Parole is Unconstitutional

Michigan and New Mexico are poised to follow Illinois’ lead. These legislative efforts come more than a decade after the Supreme Court ruled that mandatory life without parole for children violates the Eighth Amendment. The majority opinion in Miller v. Alabama established that children are constitutionally different from adults, going on to say “their lack of maturity and underdeveloped sense of responsibility leads to recklessness, impulsiveness, and heedless risk-taking. They are more vulnerable to negative influences and lack the ability to extricate themselves from horrific, crime-producing settings.”

With this decision, the Supreme Court recognized that children have both decreased levels of culpability and increased prospects for rehabilitation compared to adults. However, the high court left open the possibility of discretionary life without parole in homicide cases. Thus, lower courts across the country continue to sentence teenagers to life in cases the defendant is deemed “irreparably corrupt.” But what child is beyond repair and how can any court make such a final determination at such a young age?

The Conservative Case for Banning Juvenile Life Without Parole

At the core of conservatism lies a belief in the intrinsic worth of each individual and the capacity for personal growth. Sentencing juveniles to life without parole undermines this fundamental principle by denying young offenders the opportunity to change. Research has proven what Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy said “any parent knows” already—the human brain does not finish maturing until age 25, after which people often grow out of delinquent behavior. Therefore, children are fundamentally different from adults in key ways that must be considered during sentencing.

Life without parole constitutes an objectively harsher sentence for a 17-year-old defendant than for a 60-year-old one. Those extra years behind bars also require many more decades of public expenditures. States spend an average of $33,274 per incarcerated individual annually. This cost roughly doubles after a person turns 55. Therefore, a 50-year sentence for a 16-year-old will cost taxpayers upward of $2.25 million. In 2020, the Philadelphia District Attorney estimated the decarceration of 174 former juvenile lifers will save $9.5 million in correctional costs over the first decade alone.

There is no evidence ending juvenile life without parole has a negative impact on public safety either. That same 2020 study in Philadelphia found just a 1.14 percent recidivism rate among the former juvenile lifers released, lower than the rate for the general population. This is consistent with a growing body of scientific research that shows people age out of criminal behavior and that longer sentences fail to deter crime. Furthermore, these kinds of extreme sentences have exacerbated overcrowding in state prisons, diverting funds better used on more effective public safety initiatives.

Of course, minors who commit serious crimes should be held accountable. But a person’s age, environment and capacity for rehabilitation must be considered during sentencing. It is not surprising that childhood exposure to violence is tragically common for juveniles sentenced to life without parole. Evan Miller, the petitioner in Miller v. Alabama, was 14 at the time of the murder that led to his life sentence. He grew up in an unstable home and attempted suicide four times, starting at age 6. The reality is that Miller and many other juvenile lifers are victims themselves, damaged by dysfunctional circumstances they are too young to escape. Yet, despite his case serving as the basis for a landmark Supreme Court ruling on the subject, Miller was recently given a second life sentence without the possibility of parole.

Conclusion

Conservatives across the country have come to realize that condemning children to die in prison is an expansive government overreach by almost any definition, inconsistent with the principle of limited government. While progress has been made, the United States remains the only country that still allows juveniles as young as 13 to be sentenced to life without parole, a practice condemned by international law. There are still thousands of individuals serving life sentences for crimes they committed as juveniles. Conservatives and liberals should work together until every one of those individuals is given a chance at redemption.