Reforming the Child Tax Credit: A Look at the Family Security Act

Efforts to expand and reform the Child Tax Credit (CTC) remain a priority in discussions around family policy. The 2021 expansion of the CTC, discussed in a previous R Street post, provided significant financial relief to millions of families by increasing per-child benefits, distributing payments monthly, and expanding eligibility to lower-income households by making the credit fully refundable. These monthly payments offered families a more consistent and predictable source of support compared to the traditional annual lump sum received as a tax refund, allowing for better financial planning and stability. While this temporary measure helped reduce child poverty to a historic low, its expiration left many families facing financial challenges once again. In response, policymakers have introduced new proposals aimed at building on the lessons of 2021 while addressing concerns about sustainability, work incentives, and the role of federal family policy.

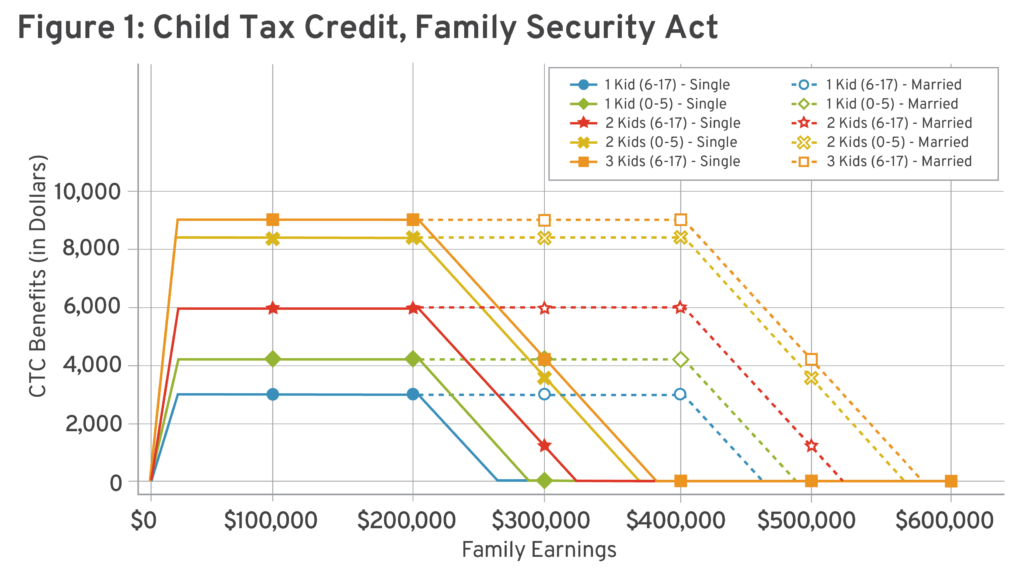

One such proposal, the Family Security Act (FSA), aims to expand the CTC by providing predictable support from pregnancy through childhood, promoting workforce participation, and simplifying existing tax benefits. Under this proposal, CTC benefits would vary by parental marital status, number and age of children, and family earnings. The FSA phases in CTC benefits with earnings, reaching a maximum of $2,000 per child and phasing out as earnings exceed $400,000 for married parents and $200,000 for single parents. Additionally, the FSA would introduce a new tax credit worth up to $2,800 for pregnant mothers, offering monthly benefits during pregnancy for the first time.

Comparison of the FSA CTC to the Existing 2024 FTC and Temporary 2021 CTC

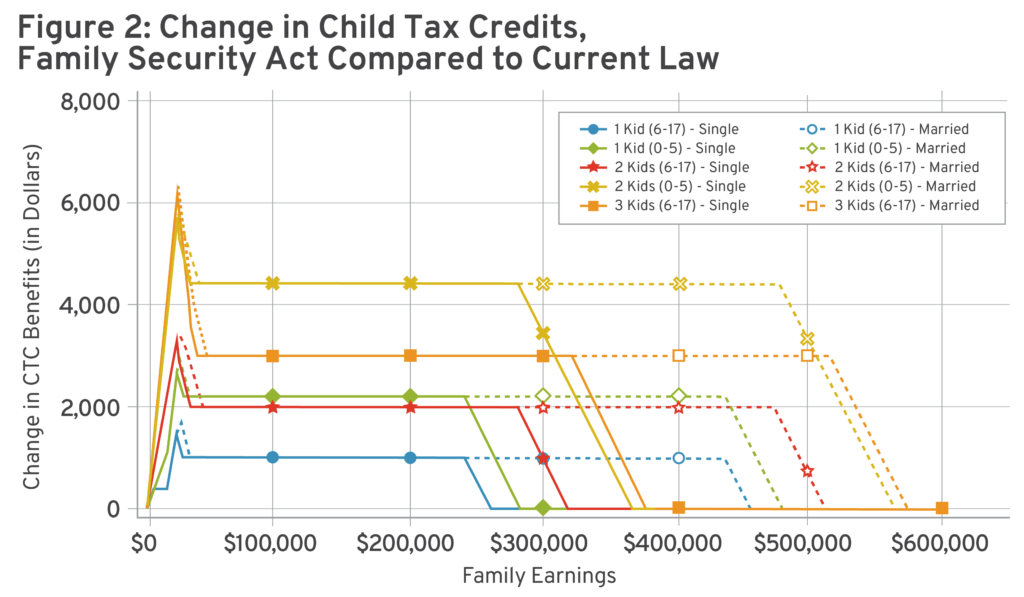

The FSA CTC preserves much of the CTC structure while increasing benefits for most families and significantly boosting support for parents with young children. Table 1 provides details on the existing 2024 CTC, the temporary 2021 CTC, and the proposed FSA CTC. Figure 1 illustrates the FSA CTC and Figure 2 shows how much the FSA CTC would expand relative to the current 2024 CTC.

Table 1: Details of Three Different CTC Programs

| CTC Program | Benefit Frequency | Max Benefits Per 0-5 Year Old | Max Benefits Per Older Child | Benefits During Pregnancy? | Income Required for Full Benefits | Income Where Expanded Benefits Begin Phasing Out (Married) |

| Current 2024 CTC | Annually | $2000 | $2000 | No | $41,000 | $400,000 |

| Temporary 2021 CTC | Monthly | $3600 | $3000 | No | $0 | $150,000 |

| Romney FSA CTC | Monthly | $4200 | $3000 | Yes | $20,000 | $400,000 |

Like the current CTC, the FSA CTC (1) includes an earnings requirement, with benefits phasing in with earnings; (2) does not provide full benefits to the poorest families; and (3) provides full CTC benefits for higher-income families, with married parents earning up to $400,000 and single parents earning up to $200,000.

Unlike the current CTC, the FSA CTC (1) raises the per-child benefit from $2,000 to $3,000 for six to 17-year-olds and more than doubles support for young children aged zero to five, from $2,000 to $4,200 per child; (2) provides CTC benefits distributed monthly, instead of just once a year as a lump-sum tax refund; and (3) lowers the earnings threshold at which families receive full CTC benefits from about $35,000 to $20,000, ensuring that more benefits go to lower-income families. This third feature increases the FSA CTC’s poverty-reducing impact compared to the baseline 2024 CTC, although it would still fall short of the temporary 2021 CTC in reducing poverty.

The FSA CTC resembles the expanded 2021 CTC in a few ways. Like the temporary 2021 CTC, the FSA CTC (1) provides benefits monthly; (2) increases per-child benefits to $3,000 (although, after adjusting for inflation, $3,000 in 2025 would be worth about a fifth less than in mid-2021); and (3) provides additional benefits for young children aged zero to five ($4,200 compared to $3,600 in 2021).

However, the FSA CTC differs from the 2021 CTC in key respects. Unlike the 2021 CTC, the FSA CTC (1) does not provide full benefits to very poor families and does not provide any benefits to the poorest families with zero earnings; (2) provides full benefits for high-income families, with the FSA CTC phasing out at $200,000 for single filers and $400,000 for married couples, far above the phase-out thresholds in 2021, which began at $75,000 for single filers and $150,000 for joint filers. More details about the 2021 CTC can be found here.

Impact on the Earned Income Tax Credit

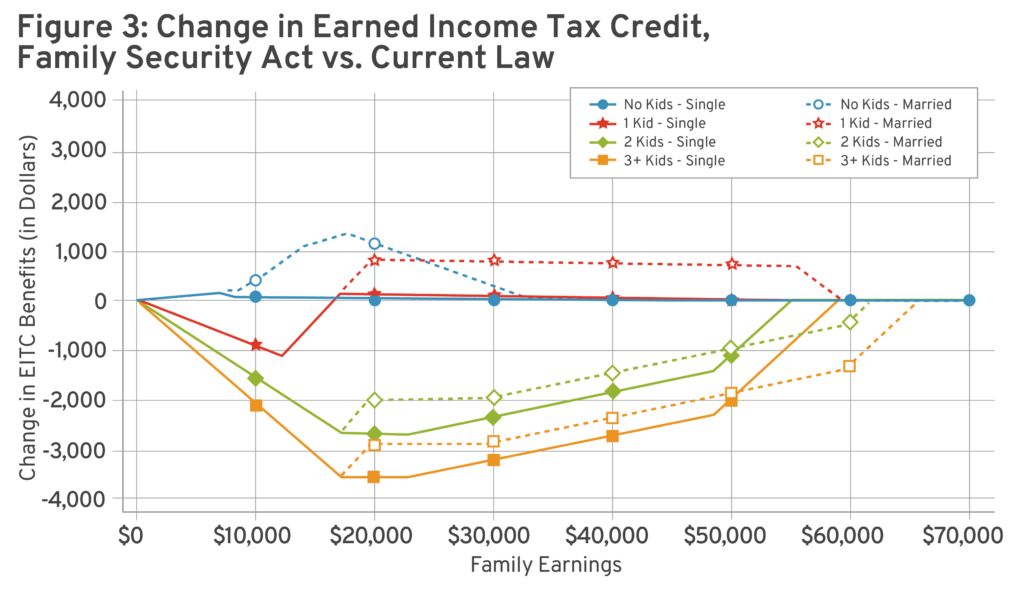

While the FSA CTC would provide $174 billion in benefits, the cost would largely be offset by reductions in five other programs (see details here), including reducing Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) payments to low-income families by $14.4 billion—shrinking the EITC by about a quarter from its current $57 billion total. Abundant research shows that the EITC helps low-income families, reduces poverty, and encourages labor force participation. To fully understand the plan’s overall impact on families, it is important to consider changes to both the CTC and the EITC. The FSA EITC would be simplified compared to the current EITC: Instead of different levels of EITC benefits available to families with one, two, and three or more children, the FSA EITC would combine these tiers into a single benefit level applicable to all families with at least one child. While this would simplify the EITC, it would also lead to reductions in benefits for most families. Figure 3 shows how much the EITC would change under the FSA relative to the current 2024 EITC. For example, lower-income families with two or more children would see significant reductions in aid of up to $3,500. Since the FSA would increase EITC benefits for married filers, some groups would see modest benefit increases—such as married families with no children or just one child—although most family types would experience EITC cuts.

Net Impact on Families

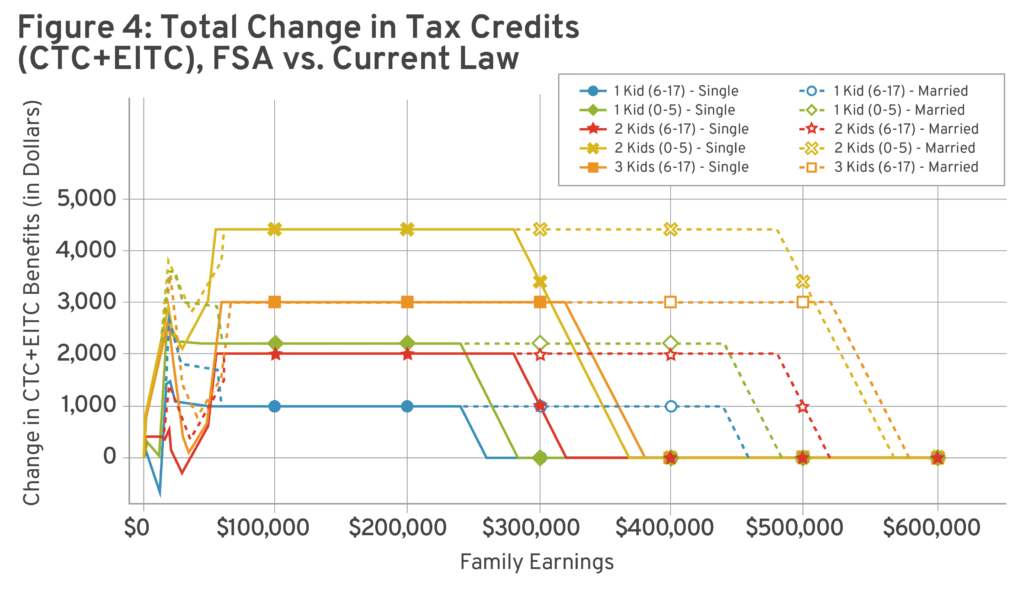

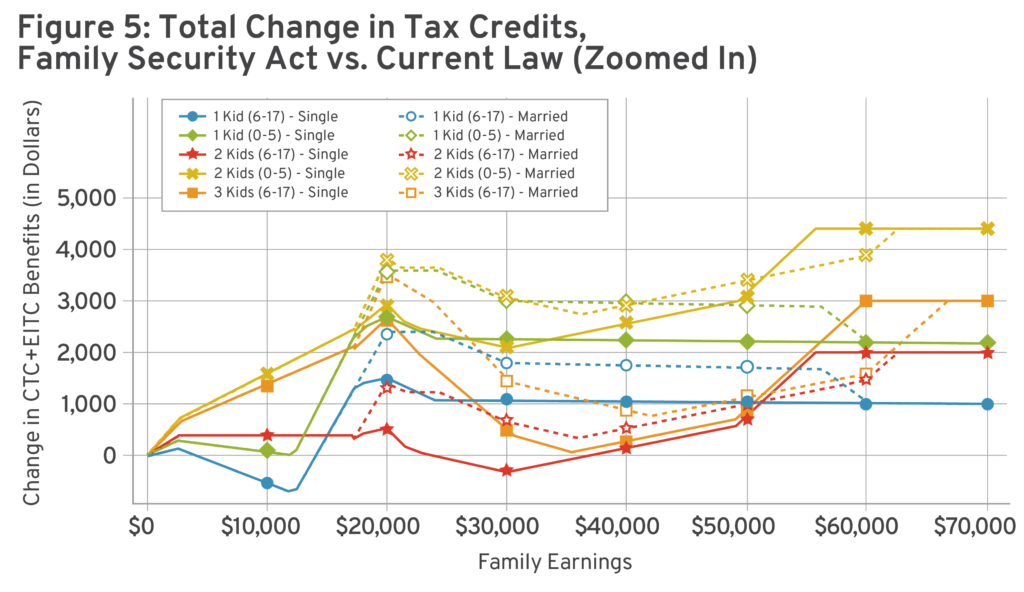

Adding up the impact of the FSA on annual CTC and EITC benefits shows the net impact of this policy on families. Figure 4 shows that almost all families would see increases in their tax credits, although tax credits would decrease for single parents with one child and incomes between about $5,000 and $15,000, and for single parents with two children and incomes between about $25,000 and $35,000. The largest increases would go to families with younger children, married parents, and higher-income families. Figure 5 zooms in to show the impact on families with annual earnings below $70,000. Overall, the increase in benefits is similar for families earning between $20,000 and $50,000, and tends to be larger for families earning above $60,000.

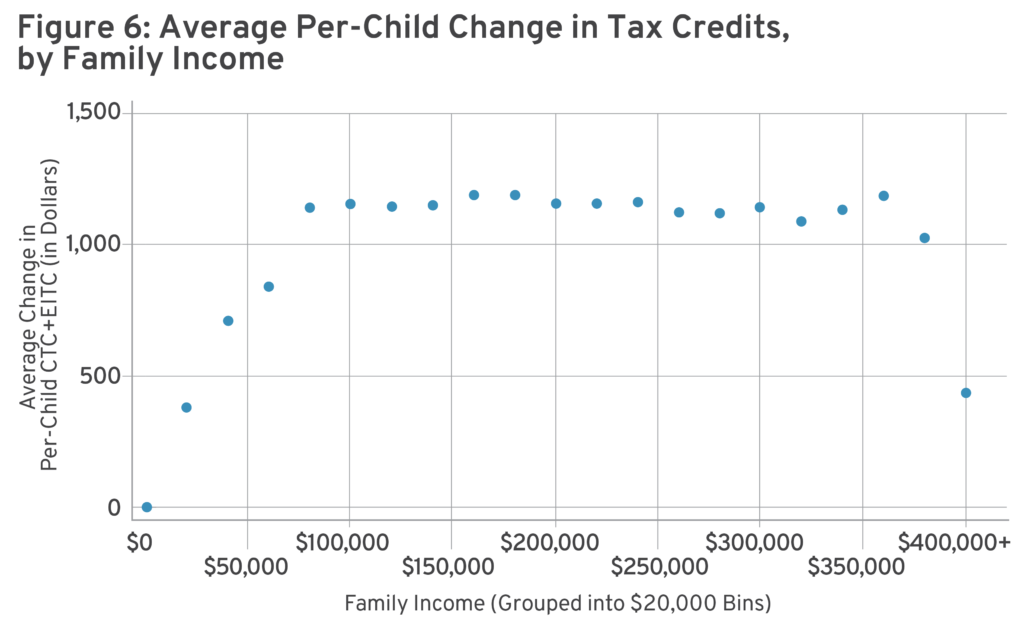

Figure 5 suggests that relatively more benefits would go to children in higher-income families under the FSA. Figure 6 examines this by analyzing Current Population Survey (CPS) data, simulating the actual change in tax credits for each family, and plotting the average change in per-child benefits across the income distribution. Figure 6 shows that the increase in tax credits is $0 for children in the poorest families with zero earnings, about $400 per child for families with positive earnings below $20,000, about $700 per child for families earning between $20,000 and $40,000, and about $800 per child for families earning between $40,000 and $60,000. For families with higher incomes—and those unaffected by reductions in EITC benefits—the average per-child increase in benefits is about $1,200. Per-child benefits for the highest income families (above $400,000) increase by a much smaller amount.

While the FSA would substantially increase benefits for millions of families, these benefits would disproportionately accrue to higher-income families. Over half of the new benefits would go to families with earnings over $100,000. Benefits for the average child in a household earning below $100,000 would be $700, compared to $1,200 for children in a family earning at least $100,000.

Policy Adjustments for Better Targeting

The CTC is a powerful anti-poverty tool, with the potential to significantly improve the long-term outcomes of children in lower-income families. While each dollar allocated to the CTC has the same fiscal cost, it delivers disproportionately greater benefits to lower-income households, who are more likely to use these funds for essentials like food, housing, and child care.

To better target support toward children in lower-income and working-class families, a few straightforward adjustments to the FSA could be made. One approach would be to avoid reducing EITC benefits for lower-income families. Another option would be to provide a small credit to the poorest families who do not file taxes or have little to no earnings.

The cost of these changes to the FSA could be offset by phasing out benefits to higher-income families earlier in the income distribution, similar to the structure of the 2021 CTC. For example, the additional CTC benefits granted to families earning over $200,000 roughly equals the reductions in EITC benefits that would impact lower-income families. While simplifying the EITC is a worthwhile goal, it is equally important to ensure that support is directed toward families with the greatest need, where the benefits will have the most substantial impact.

Providing tax credits to higher-income families yields minimal impact on child well-being compared to the transformative benefits they provide for children in lower-income households. Given this disparity in impact, along with the growing national debt and persistent annual deficits, expanding tax credits to higher-income families is an inefficient use of funds.

Conclusion

The FSA represents a significant expansion of the CTC, offering increased per-child benefits, additional support for young children, and monthly payments that improve financial stability for families. These changes hold great potential for reducing child poverty and supporting working families. However, there is reason to be concerned about distribution of benefits, as a disproportionate share goes to higher-income families, while the poorest families are left with little to no support. By refining the policy to better target lower-income households, the FSA could provide more equitable and cost-effective assistance, ensuring that resources are directed toward those who need them most and maximizing its impact on reducing child poverty.