Low-Energy Fridays: Why is coal power struggling in the United States?

Coal power drives a lot of political discussion, and notably, the Trump administration and Congress seem focused on cutting regulations and increasing subsidies to the coal industry. Ignoring the policy merits and demerits of those ideas, a more fundamental question is: Why is coal declining in the United States?

From the perspective of many politicians, if not for the “war on coal”—in which they argue Democrats are using government power to cudgel the coal industry—it would still be the country’s dominant power source. But good policy analysts should not be taken in by political rhetoric. A more grounded empirical approach to the question reveals a big disconnect between the politics and the markets.

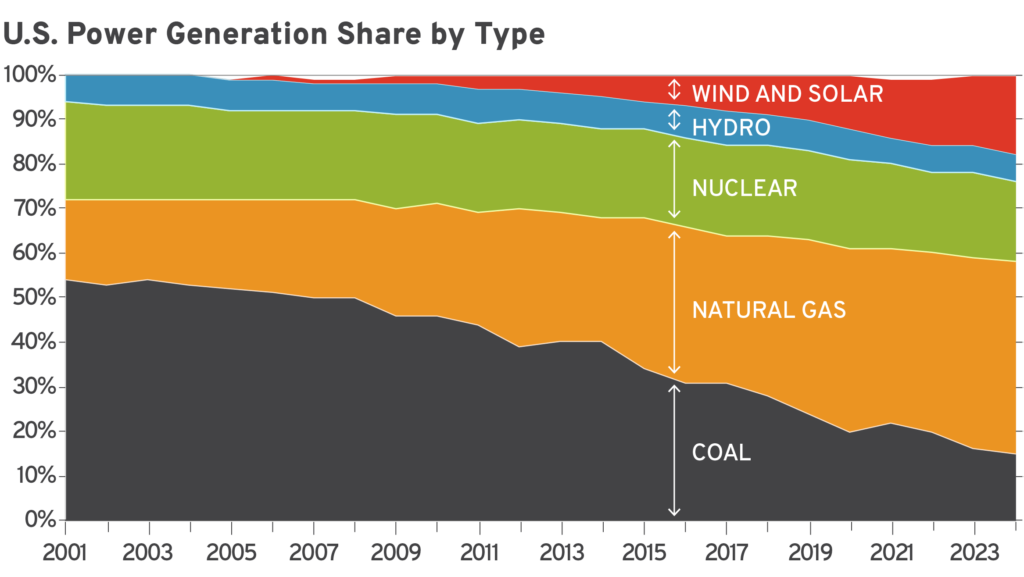

Coal used to be the primary source of electric power generation in the United States, producing just over 2,000 terawatt hours at its peak in 2007. From 2001 to 2008, coal provided roughly half of all electricity in the nation. Its share of power generation began to fall rapidly starting in 2009.

The coal industry and politicians explain this by claiming President Barack Obama’s “war on coal” and its punishing regulations made coal uncompetitive compared to politically favored industry. But if that were true, why didn’t coal rebound after Obama left office, or after those regulations were defeated in court? The problem with the political argument is that if coal really were a cheap but profitable source of energy impeded only by regulations, then we would expect to see investors risking capital on a potential future payday by investing in it—but that’s not happening. Nobody is building new coal plants in the United States. So, what else could explain coal’s decline?

Looking at other factors in the electric power sector, it’s clear that coal’s decline aligns with the increased utilization of other fuels—most notably, natural gas. While coal’s share of electricity generation decreased from 54 percent in 2001 to 15 percent in 2024, natural gas’ share increased from 18 percent to 43 percent over the same period. In other words, coal lost 39 percent of the market while natural gas picked up 25 percent. Additionally, wind and solar picked up 17 percent of the market while nuclear and hydropower together lost about 4 percent. In other words, coal shrank—and most of that market was replaced by natural gas, along with renewables.

While someone might point to renewable energy subsidies as a major contributor to coal’s woes, the comparison with natural gas is more revealing. Natural gas has not benefited from the same sort of subsidy treatment in the market as renewable energy, and as a thermal resource, it’s a more direct substitute for coal than renewables. It’s no accident that the increase in natural gas generation coincides with falling natural gas prices (thanks to directional drilling). Since 2008, natural gas prices have fallen by about 69 percent. Meanwhile, coal hasn’t gotten any cheaper—in fact, it’s increased in cost by 16 percent since 2008. Add in the fact that the thermal efficiency of natural gas power plants is also improving, and we get a clear explanation for why investors are shifting away from coal.

Stripping away the politics, the data tells an economics tale as old as time: the story of creative destruction. This is the idea that incumbent products give way to newer ones that are cheaper or better. We’re all familiar with this concept in our everyday lives—we see cars on the road instead of horses, and we use computer keyboards instead of typewriters. Creative destruction is a resisted economic force because a visible industry in decline is impacted while a hypothetical future economic benefit is harder for policymakers to see. But letting the market do its thing always leads to creative destruction, and it is through this process that we grow economically. Quite simply, this is how we improve productivity, grow the economy, and improve quality of life.

So, is there a war on coal? I don’t want to dismiss the impact of regulations out of hand; increased regulatory costs do burden industry and the economy as a whole. Some of Obama’s regulations on the coal industry were particularly egregious examples of illegal government overreach, notably the Mercury and Air Toxics Standards. But the simple observation that customers prefer coal’s competitors over coal itself is a more reasonable explanation than the idea that profit-motivated investors are somehow missing big opportunities in coal.

I won’t get too deep in the weeds on some of the recent coal-related policy changes, such as the reconciliation bill’s cutting of royalty rates or its new eligibility for subsidy under the Defense Production Act. But an empirical approach shows that coal’s decline is a result of natural market forces that replace older, less efficient ways of doing things with newer, better ones. This means that attempts to use government interventions to prop up coal power under a misguided notion of leveling the playing field will distort markets and weaken growth.

Just as last week’s Low-Energy Fridays explained that subsidies for mature technologies like wind and solar are economically damaging, so too are subsidies for coal power. The title of a past R Street piece, “Make America burn whale oil again?” also sums this up. The market delivers innovation, and politicians using government to force us backward are not practicing good economics.