If States Replace the Federal GHGRP, New Programs Will Be More Expensive

With the proposed repeal of the federal Greenhouse Gas Reporting Program (GHGRP), it is possible that states will adopt their own reporting programs to replace it. A small number of state-level greenhouse gas (GHG) reporting programs exist currently, but more are emerging in response to a potential repeal of the federal GHGRP. This analysis compares cost estimates for state reporting programs to cost estimates for the federal program to better evaluate their impact.

Background

Currently, the federal government requires all stationary facilities with an annual GHG emission rate greater than 25,000 metric tons (Mt) of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) to report their emissions to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). The GHGRP was finalized in 2009, and data collection began in 2010. In response to a methane fee implemented as part of the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act, the program’s coverage of emitter types expanded in 2024 to facilitate fee application. The One Big Beautiful Bill Act repealed the methane fee in July 2025, and the administration proposed repealing the GHGRP in September.

A handful of states already have their own reporting programs. California first proposed its Mandatory Greenhouse Gas Reporting Regulation (MRR) in 2007. The MRR, as initially proposed, had a reporting threshold of 25,000 Mt CO2e, though the current MRR has a reporting threshold of 10,000 Mt CO2e. Washington also has a GHG reporting program, first proposed in 2010, with a reporting threshold of 10,000 Mt CO2e. Oregon has its own program as well, albeit with an exceptionally low threshold of 2,500 Mt CO2e. And New York proposed a reporting program with a threshold of 10,000 Mt CO2e just this year.

Many facilities operating in states without reporting programs must still monitor and report their emissions as part of other climate-related laws. For example, the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) imposes emission requirements on power plants in Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, and Vermont. Providers in these states must continue to monitor emissions even if the GHGRP is repealed.

Related to state-level GHG reporting programs, several states—including Colorado, Illinois, New Jersey, New York, and Washington—have proposed implementing “climate disclosure” requirements for firms headquartered there. (California already has a climate disclosure law in place.) While these requirements primarily apply based on a firm’s book value rather than its emissions, they do overlap with the compliance burdens involved in data collection for GHG reporting programs.

Additionally, firms that would otherwise report data to the federal government under the GHGRP may find themselves reporting data to facilitate the necessary disclosure requirements of customers subject to higher “scopes” of emissions that include upstream sources.

State Reporting Programs Likely to Cost More

Because states do not have the same requirements for regulatory cost benefit analysis that exist at the federal level, it can be challenging to compare the quality of federal regulations to state-level counterparts. However, in the case of California’s initial proposal for the MRR a cost-benefit analysis was published. With the costs estimated around a 25,000 Mt CO2e threshold, it is possible to compare the cost of the state-designed program with the federal GHGRP.

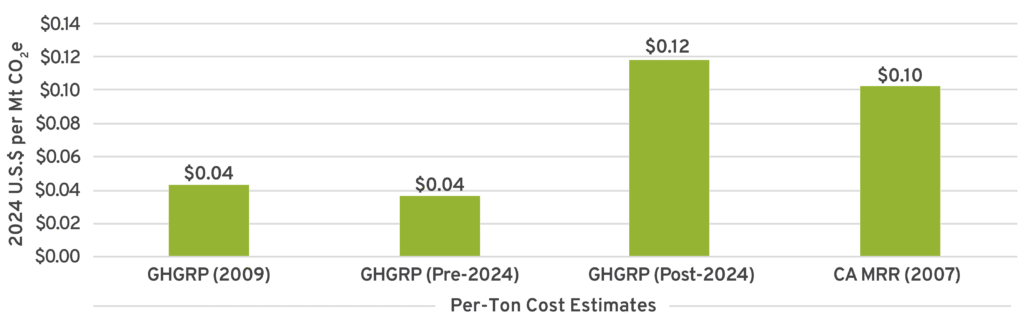

Figure 1 details the cost of GHG reporting on a per-ton basis for four estimates: The initially estimated cost of the GHGRP in 2009, the estimated cost of the GHGRP before the 2024 modifications, the estimated cost of the GHGRP after the 2024 modifications, and the estimated cost of the MRR in 2007.

FIGURE 1: Cost Comparison of Federal and California Reporting Programs

The data reveals a couple salient points. The first is that the 2024 changes substantially increased program costs, particularly relative to estimated emissions. This is because the modifications—designed to facilitate compliance with a methane fee—expanded coverage to small and/or irregular emissions that may require more resources to monitor and report relative to the mass of emission.

The second key point is that compliance with California’s MRR is considerably more expensive per ton of reported emissions than the GHGRP (prior to modification, at least). Given the considerable gap in cost between the pre-2024 GHGRP and the MRR, firms potentially covered under future state programs should expect compliance to be more costly.

State Reporting Programs Require More Reporters

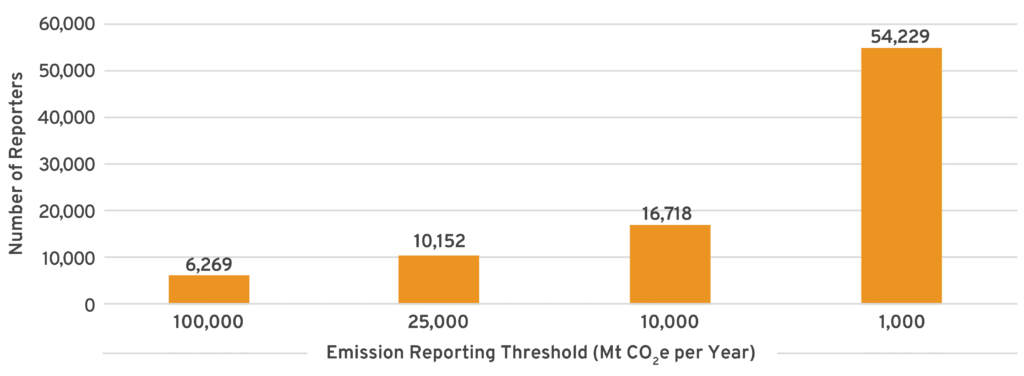

The federal GHGRP’s reporting threshold of 25,000 Mt CO2e was chosen based on the understanding that there are diminishing returns from lower thresholds as the number of reporters increases disproportionately relative to the increase in emissions reported. Figure 2 shows the estimated increase in reporters based on emission thresholds required for reporting 100,000 to 1,000 Mt CO2 per year.

FIGURE 2: Number of Reporting Entities at Various Emission Thresholds

The number of reporting entities also has a considerable impact on the estimated compliance cost. But because the newly covered emitters are smaller, the level of emissions covered is much lower. Figure 3 shows the EPA’s estimated changes in GHGRP compliance costs and emission coverage at various emission reporting thresholds.

FIGURE 3: GHGRP Costs and Emission Coverage at Various Emission Thresholds

Unsurprisingly, there is virtually no change in reported emissions at lower thresholds despite significantly increased compliance costs. Note that the EPA estimated a 33 percent higher compliance cost between the 25,000 and 10,000 Mt CO2e thresholds.

This raises concerns related to state GHG reporting programs. Since there is currently no reason for state programs to have less stringent thresholds than the GHGRP, the only examples we currently have are actually more stringent. Should other states develop their own reporting programs, they may be more inclined to set lower emission thresholds than the current federal requirement.

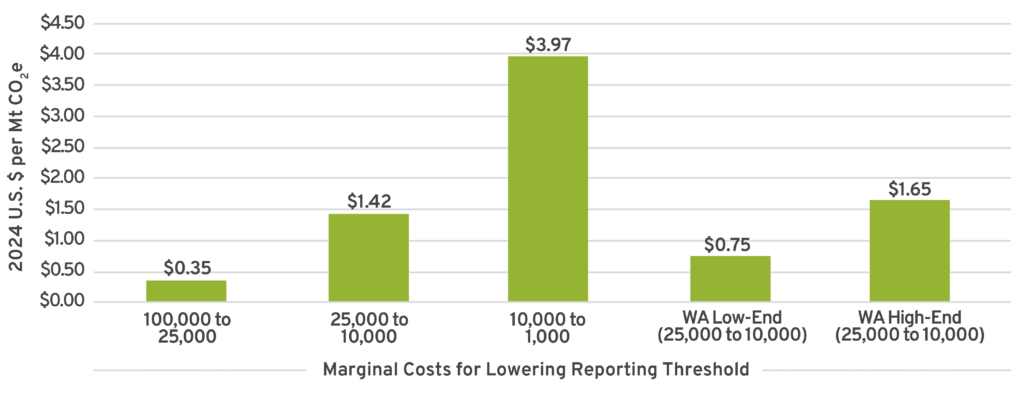

The marginal cost of lower reporting thresholds relative to reported emissions is exceptionally large. Figure 4 shows the EPA’s increased marginal cost from lowering the reporting threshold alongside the estimated cost of Washington’s marginally lower threshold (under both a low-end and high-end estimate).

FIGURE 4: Marginal Cost Increase from Lowering Reporting Thresholds

Put simply, each threshold reduction brings a marginally more expensive metric ton of GHG to report.

- 100,000 to 25,000 Mt CO2e per year: $0.35 average increase per metric ton

- 25,000 to 10,000 Mt CO2e per year: $1.42 average increase per metric ton

- 10,000 to 1,000 Mt CO2e per year: $3.97 average increase per metric ton

In Washington, where the state reporting program functionally lowers the threshold from the federal requirement of 25,000 Mt CO2e to 10,000 Mt CO2e per year, the marginal cost to report new emissions is between $0.75 and $1.65 per metric ton.

The takeaway is that a reporting program that expansively covers many small emitters—a general trend among states—is considerably more expensive. Furthermore, if states continue to develop their own GHG reporting programs in response to a repeal of the federal GHGRP, then facilities that would not have had to report their emissions to anyone before may need to begin doing so.

Other Concerns

Policymakers should also bear in mind two theoretical concerns for which limited data exists. The first is the risk of exposure to foreign reporting programs; the second is the risk of increased costs due to a complex patchwork of state-level requirements.

Risk of Exposure to Foreign Reporting Programs

Some foreign buyers of U.S. fossil fuels will be required to estimate the emissions involved in the import of such product. For example, beginning in 2027, the European Union will require energy companies to report the GHG emissions of imported U.S. product. Efforts were launched in 2024 to negotiate with the European Commission to allow the U.S. GHGRP to satisfy E.U. reporting requirements for foreign importers, although that can only occur if the GHGRP remains in force.

If U.S. energy exporters must comply with foreign requirements, then they may be forced into more costly compliance programs—or worse, governments may use a lack of emissions information to prevent trade agreements (see French company Engie as an example).

Increased Costs Due to Patchwork of State-Level Requirements

Another concern is that a surge in new state-level reporting programs could substantially increase the relative compliance costs for many firms, particularly those operating in multiple states. While some firms operating in a single state without a reporting program would benefit from a repeal of the GHGRP, it is reasonable to expect that large firms may end up with increased costs (which may manifest in states that don’t have reporting requirements, as multi-state companies may spread distribute costs among all customers).

In other words, policymakers should not assume that a patchwork of reporting programs would affect only those states that adopt such policies. And since complying with multiple programs is likely to be costlier than a single program, some firms would likely face substantially higher costs relative to the federal program.

Conclusion

In terms of per-ton costs, the GHGRP is a relatively low-cost program (though modifications made under the Biden administration have significantly increased its estimated costs). If the GHGRP is repealed, states will likely increase efforts to develop their own GHG reporting programs. Existing state-level reporting programs are considerably more burdensome due to their estimated costs to firms as well as their likelihood of requiring more reporting entities than the federal program.

While it is unclear exactly how the EPA will modify the GHGRP, it may be worthwhile to consider options that reduce program costs instead of repealing it. This may be especially important if it becomes necessary for the federal government to implement regulation that preempts state-level requirements, as is often the case with other regulatory issues.