How the EITC and CTC Work Together—and Why That Matters in 2025

When it comes to supporting families through tax policy in America, two tax credits do the heavy lifting: the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and the Child Tax Credit (CTC). Both support working families, but they serve different segments of the income distribution. The EITC is targeted toward lower-income households, while the CTC primarily benefits middle- and upper-middle-income families. Although these programs function as a pair, they rarely make headlines together.

This piece explains how the EITC and CTC work, who they benefit, how their structure shapes real-world outcomes, and how policymakers could improve them.

Two Tax Credits, Two Audiences, Two Goals

Both the EITC and the CTC provide income support to families with children, but they do so in different ways.

The EITC is a refundable credit designed to encourage work. The credit phases in with earned income, reaches a plateau, and then phases out gradually—delivering the largest benefits to those working full-time at modest wages. About 23 million households claimed the EITC in 2025, receiving an average credit of $2,700. Because the EITC requires earnings and is refundable, it’s especially powerful for working families whose earnings fall near or below the poverty line.

By contrast, the CTC is a partially refundable per-child benefit. Currently, families can claim up to $2,000 per child, with up to $1,700 refundable. However, the refundable portion phases in slowly and excludes families with little to no earnings.

While the EITC provides support and incentivizes work at the bottom of the income distribution, the CTC helps offset the costs of raising children. Their designs are similar—both phase in and out based on income—but their target populations differ. Together, they form the dual pillars of tax-based family support in the United States. The EITC cost roughly $65 billion in 2025 while the CTC, which reaches much further up the income distribution, costing over $120 billion.

How We Got Here: A Brief Legislative History

Enacted in 1975 as a modest work bonus, the EITC was expanded significantly under Presidents Ronald Reagan (1986), George H.W. Bush (1990), Bill Clinton (1993), and Barack Obama (2009). Over time, it evolved into the most effective anti-poverty program for working families. The CTC was introduced in 1997 as a nonrefundable credit worth $400 per child. It gradually grew in size and scope, with partial refundability added in the early 2000s and credit expanded to $2,000 per child in the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.

While the CTC has historically provided more support to middle- and upper-middle-income families than to those with the lowest incomes, that changed temporarily in 2021 when the American Rescue Plan transformed the credit—making it fully refundable, increasing the benefit to $3,000–$3,600 per child, and delivering payments monthly. That single year saw the child poverty rate fall to a historic low of 5.2 percent. But the expanded credit expired in 2022, and the CTC reverted to its previous structure. The impact of the rollback was immediate: The child poverty rate rose to 12.4 percent in 2022, and by 2023, roughly 6.2 million more children were living below the poverty line than in 2021. While the current CTC still reduced child poverty by 17.1 percent (from 16.5 to 13.7 percent), it doesn’t go far enough. If the expanded version of the CTC from 2021 had been in place in 2023, child poverty would have dropped by 47.9 percent to just 8.6 percent.

What the Research Tells Us

A substantial body of research confirms the EITC’s effectiveness—not only in reducing poverty, but also in boosting employment, especially among single mothers, and improving long-term outcomes for families. These gains also reduce reliance on other government assistance, making the EITC relatively inexpensive. After accounting for higher tax payments and reduced spending on programs like food stamps and welfare, the net cost to the government is just 17 cents for every dollar of benefits delivered. Few social policies combine such strong antipoverty effects with such low net cost. Beyond labor markets, the EITC also delivers intergenerational benefits: Children in EITC-receiving families are healthier, more likely to finish high school and college, and go on to earn more as adults.

The CTC’s impact on a number of important outcomes is smaller because each dollar of support has a smaller effect on children from higher-income families than from lower-income families. Because the CTC focuses on higher-income families and reaches further up the income distribution, it’s also less targeted—which dilutes its per-dollar impact compared to the EITC.

How the EITC and CTC Interact

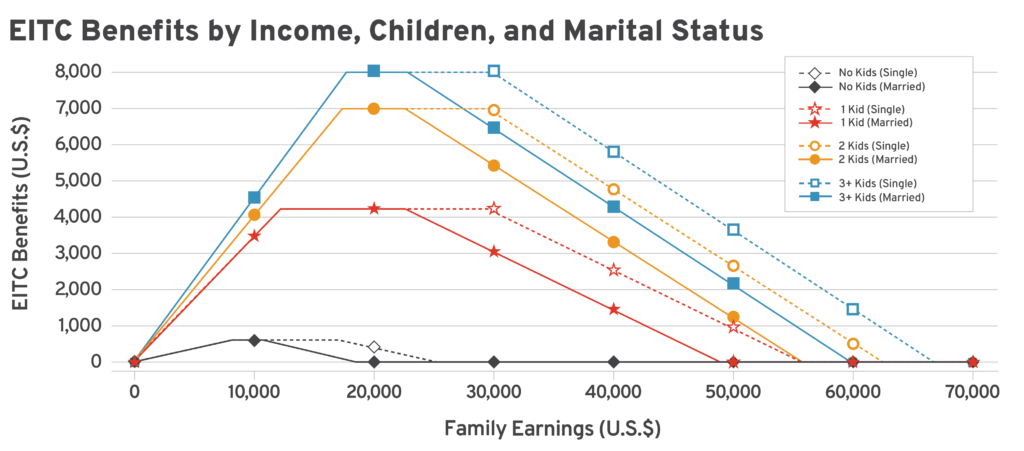

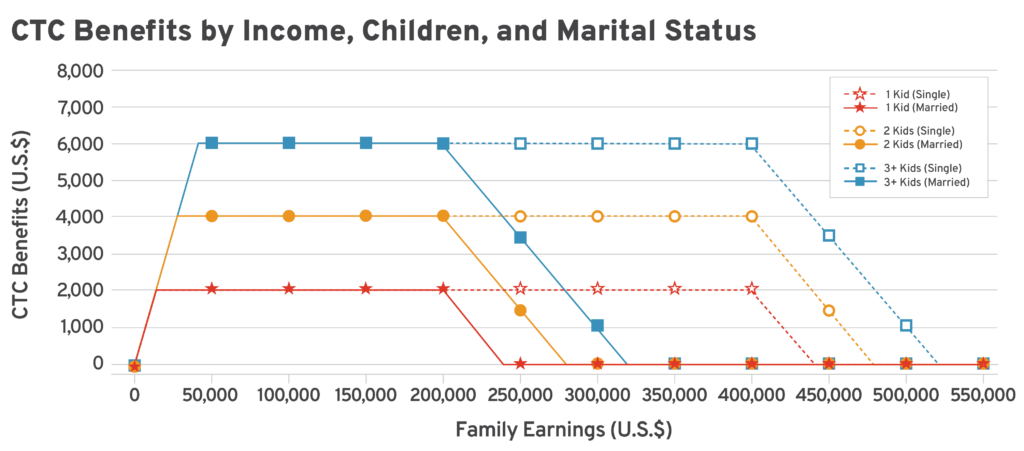

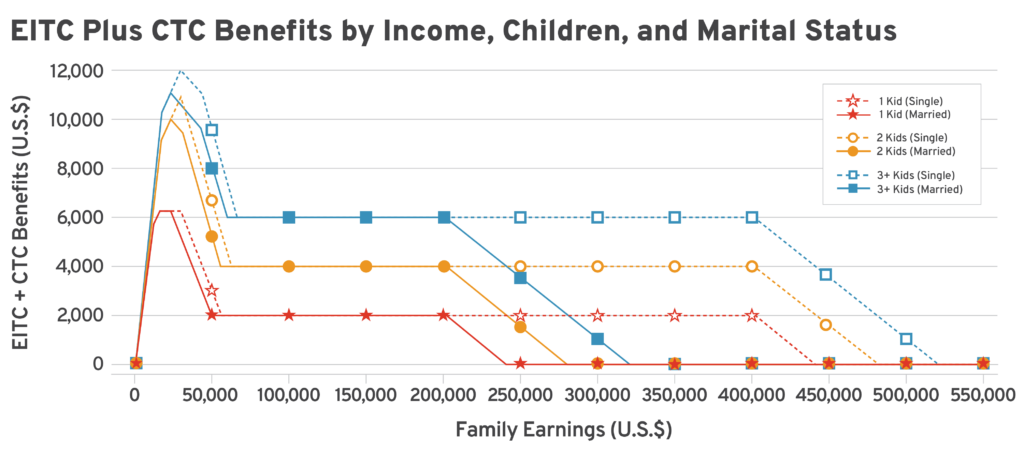

The following three figures illustrate how the EITC and CTC operate individually and together across income levels, family size, and marital status, showing that the credits often work in tandem, though not equally. The EITC provides the lion’s share of support for lower-income families, while the CTC’s refundable portion may be small or nonexistent. Moderate-income families benefit from both: For example, a two-parent household earning $30,000-$50,000 with two children might receive over $8,000 combined. The EITC phases out at higher incomes, but the CTC remains—often delivering $4,000 or more for two children. The EITC ramps up quickly with earnings, peaks at modest wages, and phases out entirely around $50,000-$70,000. The CTC grows more slowly due to limited refundability and then flattens across the middle class, phasing out only above $200,000 (single) or $400,000 (married).

Taken together, the figures reveal a system that delivers substantial support to low-income working families, levels off through the middle class, and declines at very high incomes—underscoring the credits’ complementary design and the gaps that remain for families with very low earnings or limited tax liability.

Over 90 percent of EITC dollars go to families earning under $40,000, with about half going to single mothers—making it one of the most progressive parts of the tax code. The CTC skews higher up the income ladder: In 2023, 70 percent of its dollars went to families earning above $50,000, while those earning under $30,000 received less than 10 percent of the benefits. Because full benefits extend to households earning up to $400,000 (married) or $200,000 (single), the credit directs substantial resources to higher-income families—disproportionately excluding Black and Latino children, who are more likely to live in low-income households. As a result, the CTC is both more costly and less effective at reducing poverty than the EITC.

What Policymakers Should Take Away

The EITC and CTC are complements, not substitutes. Universal benefits like the CTC may be politically appealing, but the EITC delivers more impact per dollar by targeting families who need it most. Future reforms should strengthen both credits by addressing a number of key design flaws. For example, although not directly aimed at families with children, the EITC’s treatment of childless workers is a major weakness; it currently offers less than $600 annually to this group. Addressing this flaw matters not only for fairness, but also because many workers view financial stability as a necessary condition for starting a family. Expanding the EITC for these workers would reduce poverty and potentially support family formation.

Furthermore, the CTC should be made fully refundable—or at least phased in more quickly—so low-income families aren’t excluded. Policymakers should consider periodic benefit delivery, as 2021’s monthly CTC payments improved financial stability and reduced hardship by helping families cover essentials like food, rent, and utilities.

Increasing take-up rates is essential, particularly for the EITC, which nearly one in five eligible families fails to claim. Commonsense reforms should simplify access by allowing families to claim these credits automatically when eligible, providing pre-filled tax forms, and expanding the availability of free, easy-to-use filing tools. Congress’s recent elimination of the IRS Direct File program—an option that made it easier for low-income families to file taxes—was a step in the wrong direction. Policymakers should invest in outreach efforts during tax season and resist proposals that impose new procedural hurdles (e.g., pre-certification), which add red tape and risk pushing families out of the system.

Conclusion: Support That Works—If We Get It Right

The EITC and CTC are two of the most important tools the federal government has to support families with children. The EITC is highly effective at reaching low-income working families and reducing poverty. The CTC delivers benefits to a larger set of families but largely misses those at the bottom. Recent legislative changes expanded the CTC modestly, but most of the new dollars will flow to middle- and upper-income households. To make real progress, future reforms should focus on boosting support where it has the greatest impact: among families with children working hard to make ends meet. Done right, these two credits can do more than alleviate poverty—they can expand opportunity, strengthen the next generation, and show our commitment to supporting the families who need it most.