Four Half-Measures to Stem Postal Pension Losses

A few weeks ago, the United States Postal Service (USPS) released its annual financial report. While there were some points of hope—weakening mail revenue was covered by more parcel income—USPS retiree obligations continue to grow. As in each of the previous four years, 2019 saw the government mail enterprise post new highs for how much it needs to save to pay for its promises to past and current employees.

Between 2018 and 2019, total liabilities for retiree pensions and healthcare increased from approximately $48 billion to more than $55 billion. With workers’ compensation costs, debt and total liabilities, the agency will likely owe more than $100 billion within the current fiscal year. While the USPS has many problems, dealing with this debt remains the most pressing issue in American postal policy. With the prospect of reducing retirement compensation a political nonstarter for the foreseeable future, policymakers have a limited number of options to address the USPS’ retiree obligations. I address four such options below.

The most talked-about response to growing postal retiree costs revolves around shifting the burden of postal retiree benefits from the Postal Service to some other government account. This could be Social Security, the federal Basic Benefit Plan or some other entity that draws on funds beyond postal service revenue. Proposals that rely on such transfers would address the burden of retirement liabilities and their requisite savings in the immediate term, but have their own costs. $55 billion is no small sum. Shifting that to the books of the Social Security Administration or one of the federal employee retirement plans would only force legislators to find the money elsewhere in the federal budget.

And it wouldn’t be costless for the USPS. As a government entity that’s expected to be self-financing, a transfer of retirement liabilities to federal taxpayers would signal that the postal service can no longer stand on its own. For taxpayers, the deal would be even worse, as separating responsibility for USPS retirement finance from postal labor policy would remove one of the key policy checks on increasing USPS labor costs.

A second option would allow postal pension funds to be invested in all assets USPS fund managers see fit. This broad mandate to maximize returns for current and future USPS retirees would avoid categorical bans on types of asset investments.

While this may seem intuitive, postal law today requires a strategy akin to the opposite of that mandate. Postal retiree savings must solely be invested in special-purpose treasury bonds designed to minimize risk of loss. A limited risk of loss sounds important for a government enterprise. It shelters postal retirees when the economy turns downward. But when losses are mounting despite a growing economy, the current investment rules prevent the agency from earning market returns on the assets it saves. Had rules been changed a few years ago, there’s a chance, per a USPS Inspector General’s office study, that postal pensions would be almost fully funded in the next decade or so. They didn’t stop there: A further study from 2019 demonstrated that this policy quirk is unique among major world postal operators. Of the 11 studied postal operators, only the USPS keeps all its funds entirely in a single asset class—bonds. Repealing this mandate would open the USPS to new financial risk, but shifting pension investment rules to resemble the USPS’ peers around the world could prevent the need for even harder choices about postal finances in the future.

But even this might be too much change in a slow-moving policy area such as postal reform. A third path would change the USPS retirement investment rules to mirror those that apply to the savings of federal employees enrolled in the Thrift Savings Plan for all or a portion of postal retirement savings. This is the core principle behind one existing reform bill currently proposed in Congress. The bill would require the Treasury secretary to invest 25 percent of the postal retiree healthcare fund in such a manner, with the ability to rise to 30 percent after five years. Though it would only liberalize rules for a portion of one of the three USPS retirement funds, such a step would support later, more broadly applicable reforms.

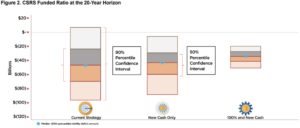

Should this be too much for postal policymakers, the Treasury could take modest steps to improve postal pension management without new legislation. The Treasury secretary has authority to allow the federal Office of Personnel Management to shift some funds into Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS)—an authority which has not yet been invoked. This could modestly increase the return on postal pension investments, as shown in yet another USPS OIG study. The study demonstrates that investing new or existing retirement funds in TIPS rather than existing fixed-rate securities would narrow the range of potential returns over 20 years while improving the funds’ overall funding ratio.

(Source: USPS OIG)

None of these will fix the major structural problems at the USPS. Mail is still in decline, and healthcare and retirement costs continue to rise each year. But policymakers should find hope in the fact that there remains some low-hanging fruit in postal finance: changing postal pension investment rules.

For more on postal pension reform, see our previous work or attend our upcoming event.