Democrats’ Reconciliation Bill Highlights Two Ways Senate Debate May Unfold

Democrats are one step closer to passing the Inflation Reduction Act reconciliation bill through the Senate before the start of the chamber’s August recess. Before beginning debate on the bill – negotiated by Joe Manchin, D-W.Va., and Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y. – Democrats first needed the House to send the Senate its version of the reconciliation bill – the Build Back Better Act (HR 5376). When the Senate received HR 5376 earlier this week, Democrats began the Rule XIV process for HR 5376 by bypassing the committee stage of the reconciliation process. Democrats placed the House-passed bill directly onto the Senate’s calendar of business to save time.

Schumer completed the Rule XIV process for HR 5376 on the following day when he objected to the bill’s second reading. The presiding officer then placed it directly onto the Senate calendar as required by Rule XIV.

Before a senator can move to begin debate on HR 5376, Rule XIV requires that it “lie over for one day” after being placed on the calendar. Therefore, any senator can force a vote on starting the reconciliation debate after HR 5376 has been on the calendar for one day (absent unanimous consent) by making a motion to proceed to its immediate consideration. The Senate votes on the motion to proceed immediately after a senator makes it because reconciliation bills are privileged under the 1974 Budget Act. “Privilege” means that senators cannot filibuster the motion or bill.

The text of the Inflation Reduction Act released by Democrats indicates that they will offer it as an amendment to HR 5376 whenever the Senate votes to start the reconciliation debate. And how Democrats drafted the amendment indicates how the reconciliation debate is likely to unfold on the Senate floor.

CATEGORIZING AMENDMENTS

The Senate categorizes the amendments that senators may offer on the floor in three ways.

FORM

The first way is by form. An amendment’s form is determined by its instructions – what the amendment does to the underlying measure. An amendment may either add text to the underlying measure, remove text from the underlying measure, or remove text and add text to the underlying measure at the same time. These actions correspond to three different amendment forms: an amendment to insert, an amendment to strike, and an amendment to strike and insert.

TYPE

The second way that the Senate categorizes amendments is by type. The Senate determines an amendment’s type by how it changes the underlying measure. An amendment is either a perfecting amendment or a substitute amendment. A perfecting amendment seeks to make a minor change to the underlying measure – it tweaks or perfects the underlying measure. In contrast, a substitute amendment aims to make a more substantial change to the underlying measure – it substitutes new text for a title, section, or subsection of the underlying measure. A complete substitute – or an amendment in the nature of a substitute (ANS) – substitutes new text for all of the text in the underlying measure.

Perfecting amendments can take any form. Senators can draft them as amendments to insert, to strike, or to strike and insert. In contrast, substitute amendments can take only one form. Senators can draft them only as strike and insert amendments.

DEGREE

The third way that the Senate categorizes amendments is by degree. Senators can offer first- and second-degree amendments. First-degree amendments are amendments that senators offer directly to the underlying measure. A second-degree amendment is any amendment that a senator offers to a first-degree amendment. The Senate’s precedents – but not its rules – bar senators from offering third-degree amendments (amendments to a pending second-degree amendment to a pending first-degree amendment) in most scenarios (see below).

IMPLICATIONS

How the Senate categorizes amendments is important because the form and type of the first amendment (e.g., the Inflation Reduction Act) that a senator offers to a bill or resolution (e.g., HR 5376) determine senators’ amendment opportunities in the subsequent debate. The amendment’s form and type also determine the majority leader’s options for controlling that debate by blocking senators’ amendments. In the reconciliation process, the majority leader cannot use these options to prevent senators’ from offering amendments during vote-a-rama, which occurs at the end of the debate. (The majority leader has other options for managing the amendment process during vote-a-rama that may make it harder for senators to offer amendments during that stage.)

The range of possible amendment opportunities created by the first amendment offered to a bill or resolution is depicted in the four amendment trees – or charts – below.

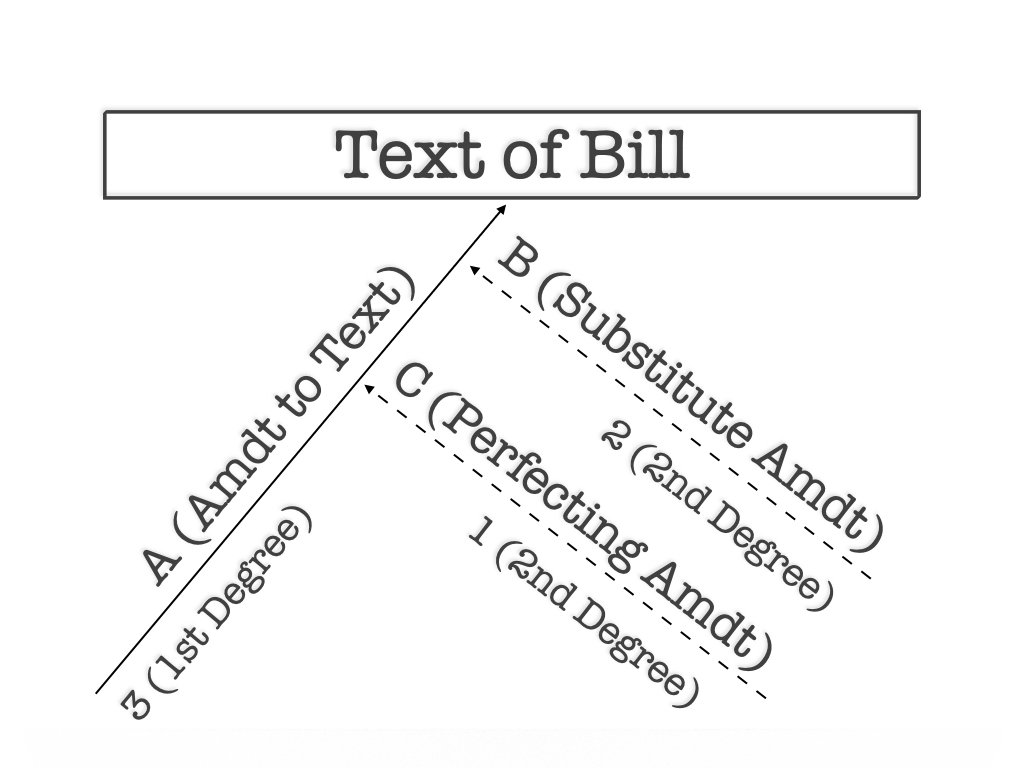

CHART 1

Amendment to Insert

CHART 2

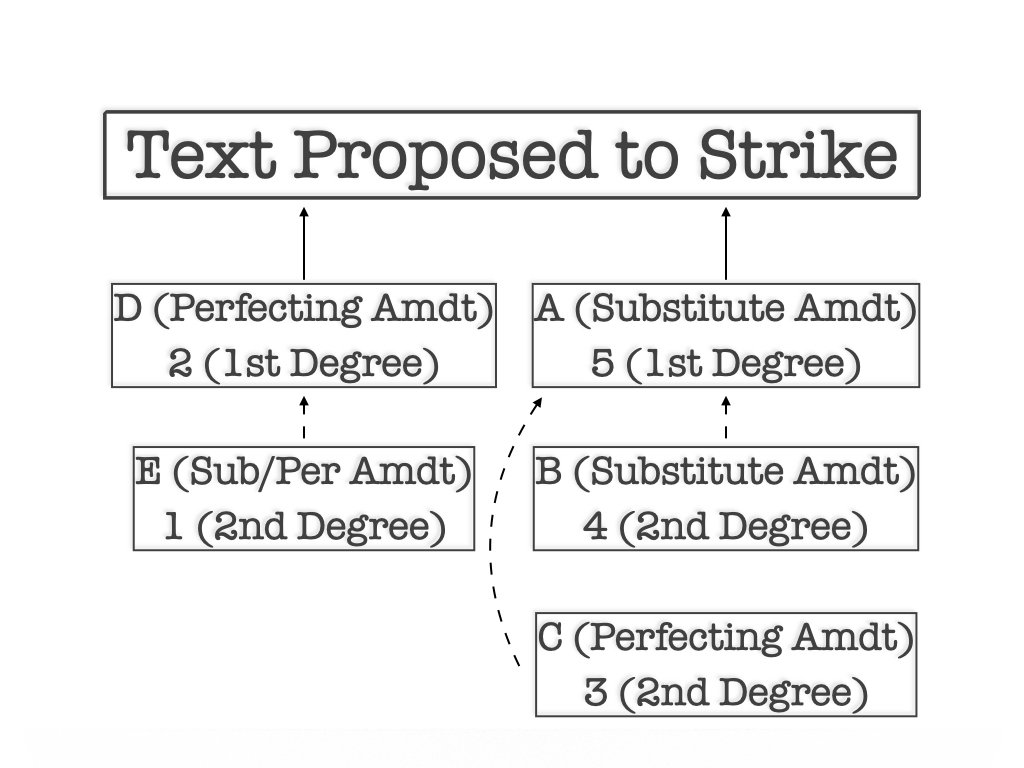

Amendment to Strike

CHART 3

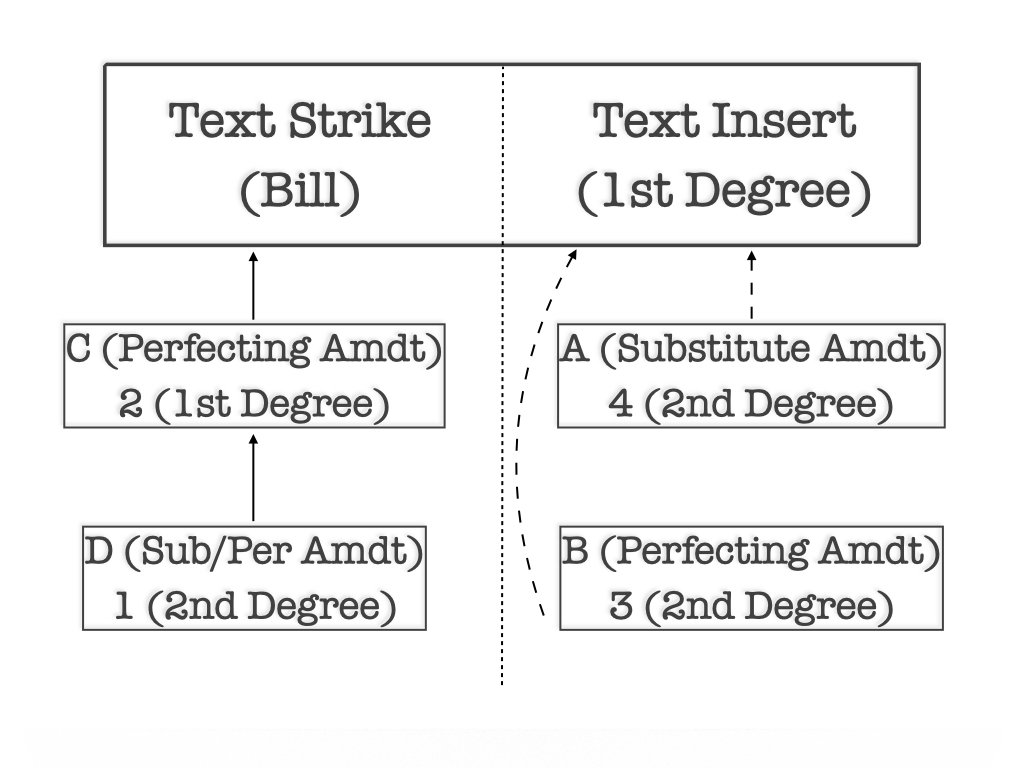

Amendment to Strike and Insert

CHART 4

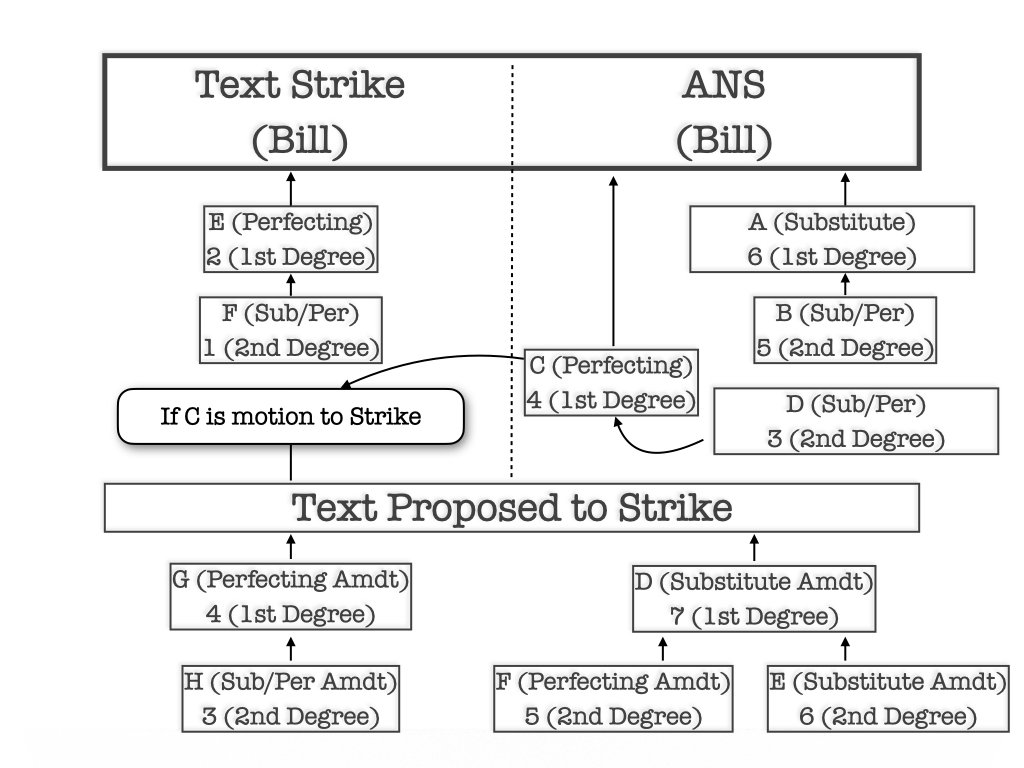

Amendment to Strike and Insert (a complete substitute)

In charts 1 and 2, the first amendment that a senator offers to the underlying measure is a perfecting amendment. In charts 3 and 4, the first amendment that a senator offers to the underlying measure is a substitute amendment. Chart 3 depicts the opportunities that are created when that amendment is a regular substitute. Chart 4 illustrates the opportunities created when that amendment is a complete substitute – or an amendment in the nature of a substitute (ANS).

Senate Democrats drafted the Inflation Reduction Act as a complete substitute amendment for HR 5376. It strikes all of the text in the House version of the reconciliation bill and replaces it with the Senate’s version. Consequently, the opportunities senators have to amend HR 5376 before vote-a-rama are depicted in Chart 4. As always, senators may create new opportunities by unanimous consent that are not shown in Chart 4.

WHY CHART 4 IS DIFFERENT

Chart 4 depicts the Senate’s most complex amendment process that its rules and precedents authorize. It dates to 1874. Senators adopted a new rule that year – today’s Rule XV – which eliminated the ban on third-degree amendments to complete substitutes. Instead, the new rule requires senators to treat a complete substitute and the underlying measure that it seeks to amend as separate questions for the “purposes of amendment.” In other words, the complete substitute and the underlying measure are both original text, or bills, to which senators may offer first- and second-degree amendments on the Senate floor.

While the 1874 rule change laid the foundation for Chart 4, it did not create all of the branches that the chart depicts. Senators created those branches instead whenever they confronted specific situations in which the 1874 rule was silent or ambiguous. Their decisions on how to proceed in those situations created new precedents that continue to guide senators today. Under those precedents, the left and right sides of Chart 4 depict separate “trunks” that can each support “branches” to accommodate senators’ first- and second-degree amendments. Senators may offer third-degree amendments on the right side of the tree. They can offer only first- and second-degree amendments on the left side of the tree. (Only one complete substitute can be offered to the underlying measure at a time.)

TWO OPTIONS

Chart 4 also highlights two ways Majority Leader Schumer can prevent senators from offering amendments to HR 5376 before vote-a-rama.

OPTION 1 – FILL THE TREE

Schumer may offer the Inflation Reduction Act to HR 5376 and then use his priority of recognition to prevent rank-and-file senators from offering further amendments by filling the tree. To fill the tree, Schumer has to offer back-to-back amendments – which can be perfunctory – to HR 5376 at each branch depicted in Chart 4. No further amendments are in order (absent unanimous consent) once all branches are occupied. Filling the tree allows Schumer to line up the votes for the Inflation Reduction Act ahead of vote-a-rama without worrying about a disgruntled Democrat or Republican jeopardizing its passage by offering an amendment that splits his caucus.

OPTION 2 – OFFER A BLOCKER AMENDMENT

Schumer may offer the Inflation Reduction Act to HR 5376 and then use his priority of recognition to prevent rank-and-file senators from changing the bill significantly by offering a blocker amendment. In doing so, Schumer creates the appearance of a free amendment process while ensuring that nothing important happens before vote-a-rama. For example, Schumer can offer an amendment to insert or an amendment to strike and insert to branch C depicted in Chart 4. (Note: Schumer is unlikely to draft his blocker amendment as an amendment to strike because doing so would give senators more amendment opportunities than they would otherwise have.) Once Schumer’s blocker amendment is pending, senators need unanimous consent to offer amendments directly to the complete substitute (i.e., the Inflation Reduction Act) that Democrats want to protect.

Offering a blocker amendment is less aggressive than filling the amendment tree entirely because it leaves a few branches open to which senators may propose amendments. But these branches are not directly connected to the complete substitute. For example, in the scenario above, Schumer’s blocker amendment at branch C leaves branches E and F (on the left side of the tree) open. Schumer’s maneuver also leaves branch D (on the right side of the tree) open. But these branches do not pose the same threat to Democrats as branches directly connected to the complete substitute. The impacts on the Deficit Reduction Act of an objectionable amendment at branches E, F, and D are manageable. Schumer can move to table his original blocker amendment at branch C to prevent a vote on an objectionable amendment at branch D. And adoption of objectionable amendments at branch E or F can be overridden by approving the complete substitute at the end of the process.

THE TAKEAWAY

How Democrats drafted the Inflation Reduction Act determines senators’ amendment opportunities before vote-a-rama. It also highlights two ways Schumer may prevent senators from offering amendments to the Inflation Reduction Act or HR 5376 before vote-a-rama begins.