Breaking the Fever: Inside One City’s Bold Plan to Stop the Spread of Violent Crime

In 2020, while the world battled one pandemic, a different kind of outbreak in St. Louis, Missouri, reached a fever pitch. It had its own transmission vectors and hotspots, spreading from person to person and overwhelming the city’s defenses. As fatalities hit a 50-year peak, the epidemic felt like a permanent, incurable fact of life. But the death and suffering weren’t caused by a novel virus or force of nature—it was something far more intimate and entrenched: lethal violence.

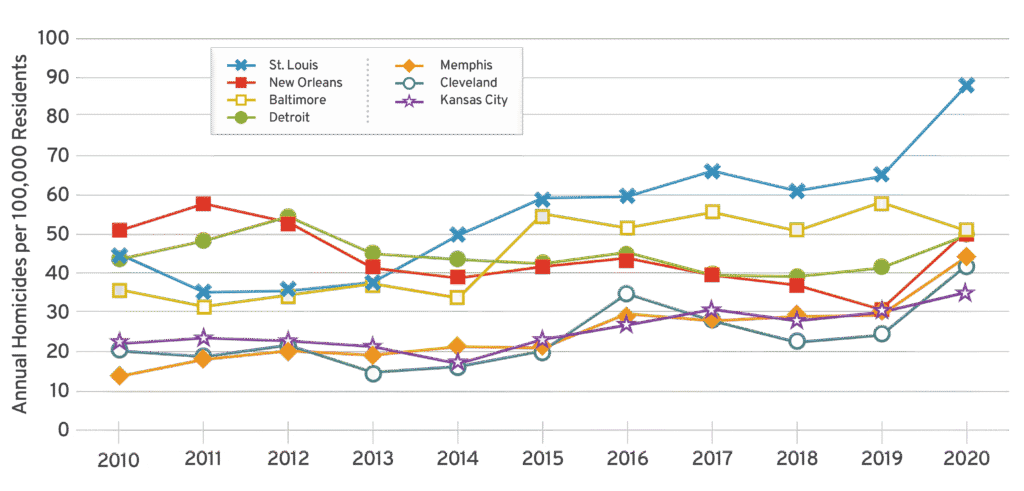

Annual Homicides Per 100,000 Residents

For seven years, St. Louis had among the highest per-capita homicide rate for cities with 250,000 people or more.

Yet, against this bloody backdrop, a new story began to unfold. Over the past four years, St. Louis has witnessed a remarkable and sustained decline in murders. By 2023, homicides had dropped to their lowest point in a decade—a staggering 39.1 percent reduction since the peak. Other key indicators like “shots fired” calls and juvenile shooting victims are also trending downward. This turnaround isn’t the result of getting “tough on crime” or deploying the military on the streets; it’s due in large part to a group of people with a shared belief: that violence behaves like a disease—one that can be diagnosed, treated, and even cured.

The CVI Ecosystem

The backbone of this network is the city’s Office of Violence Prevention (OVP), established in July 2022 as a central hub to coordinate and fund community violence intervention (CVI) strategies. This move marked a critical turning point, transforming what was once a collection of promising but isolated community programs into a unified, city-wide public safety apparatus.

According to Brett DeLaria with OVP, the goal is to “create a truly integrated and strategic approach to violence reduction.” Relying on a combination of street outreach, cognitive behavioral therapy, and focused deterrence, CVI provides a pathway out of violence, inoculating communities at the source of the infection.

While many factors influence urban crime trends, a more granular look at the data from St. Louis provides evidence for CVI’s direct impact. From 2023 to 2024, the specific neighborhoods targeted by the OVP saw a 52 percent decrease in murders and non-negligent manslaughter, significantly outpacing declines seen elsewhere in the city. This data point is critical because it functions as a natural experiment: In locations where the city tried CVI, the results were disproportionately positive.

| Metric | 2024 (Latest Full Year) | % Change (2023-24) |

|---|---|---|

| Homicides (City) | 150 | -6% year-over-year |

| Juvenile Shooting Victims | 63 | -6% year-over-year |

| Shots Fired Calls | 5,021 | -13% year-over-year |

| ShotSpotter Activations | 9,204 | -18% year-over-year |

Just as a compromised immune system makes infection more likely, violence thrives in environments weakened by poverty, housing instability, and generations of segregation and disinvestment. As in any other city, violence in St. Louis isn’t random—it’s highly concentrated. In 2022, over 90 percent of regional homicides happened in either St. Louis County or St. Clair County. Across these jurisdictions, violent crime clusters among hotspots that account for a disproportionate share of the region’s shootings.

Just as epidemiologists track a disease to its source, CVI programs identify the specific individuals and locations at highest risk.

Pillar 1: Interrupt Transmission

Jason Watson, who runs the Show Me Peace violence interruption program, is a self-described “reformed street dude,” a euphemism for what academics like to call a “credible messenger.” Growing up on the streets of north St. Louis’ Walnut Park, Watson lost his best friend in a shooting as a teenager.

Watson’s authority comes not from a badge, but from this experience. It gives him insight into what he calls the “inherited mindset” of vengeance, explaining that intergenerational violence is a direct result of personal and systemic trauma. This on-the-ground diagnosis is confirmed by research showing that victims and suspects in St. Louis share nearly identical demographic profiles and criminal histories, averaging 13 prior arrests each.

Stopping an epidemic requires finding people with the right antibodies. Watson intentionally hires street outreach workers with “edgy” backgrounds and past involvement in the justice system. This insider status is their greatest asset, granting them a level of trust and influence that police can’t replicate. Using an intelligence network built on personal relationships, the mission is to interrupt violence before it starts. “The streets know things before the police do,” Watson says. Transforming a criminal record from a liability into a unique qualification, this model also creates one of the most effective pathways to stable employment for formerly incarcerated people.

Watson says that violence is often not an act of hate or anger, but a warped expression of love and respect. Under this mindset, retaliating for a fallen loved one feels like a necessary act of loyalty. “Imagine if loving my brother looks like me hurting you,” Watson says, capturing the twisted social contract that perpetuates cycles of grief and revenge. The goal of his work is to reframe that definition of love: “It’s not about killing to prove your commitment; it’s about living for the person you lost.”

Pillar 2: Heal the Patient

When street-level interruption fails and a bullet finds its mark, the fight to stop the spread moves to a different theater: the hospital emergency room. Hospital-based violence intervention programs engage victims and perpetrators in the immediate aftermath of a violent injury. This is a critical window to begin healing, address trauma, and prevent retaliatory attacks.

In St. Louis, the Life Outside of Violence (LOV) program is the heart of this strategy, anchoring a continuum of care that aims to break the cycle of violence. Beginning at the hospital bedside, LOV staffers offer psychological and social support services in addition to medical care. These include substance abuse treatment, housing and transportation assistance, food aid, and help navigating complex medical and legal paperwork.

“Think of the emergency department as ground zero,” says Program Manager Melik Coffey. “A gunshot wound is not only an injury to the body. It is an injury to the whole of one’s self.”

Housed at Washington University’s emergency medicine department, LOV’s most unique feature is its collaborative data-sharing agreement, allowing the program to operate across four Level-1 trauma centers in two separate hospital systems. This partnership breaks down institutional silos, ensuring care is available regardless of where a person is taken for treatment.

According to Clinical Case Manager Keyria Page, violence does not respect jurisdictional boundaries. In this way, LOV prevents people from becoming “victims of their zip code,” ensuring a patient’s location doesn’t determine their access to critical support. Despite operating in hospitals, the majority of LOV’s work happens after the patient is discharged. “We can’t send someone back to the place they were hurt and expect them to heal,” Page said.

Lori Winkler, a nurse who came out of retirement to join LOV, vividly illustrates LOV’s commitment to holistic care. In one instance, when a young parent complained about their lack of sleep, Winkler gently picked up their baby and conducted an impromptu infant sleep tutorial on the spot. The ability to quickly react to a patient’s evolving needs exemplifies the essence of wraparound care: It is practical, responsive, and individualized.

Pillar 3: Boost Immunity

The final stage in a public health approach to violence reduction is to boost immunity, build long-term resilience, and shift community norms. St. Louis’ Bullet Related Injury Clinic (BRIC) is pioneering this work. A prominent St. Louis trauma surgeon founded the organization out of frustration at the common but little-known hospital protocol of leaving bullets inside a victim’s body if they pose no immediate medical threat. Not only do leftover bullet fragments cause chronic pain, they as a constant reminder of one of the worst things a person can experience.

He realized that the healthcare system was a revolving door—excellent at saving a life, but terrible at helping someone live. The BRIC was founded on a simple but radical model: Provide a free clinic that requires no ID, no insurance, and even offers free rides to remove every possible obstacle to care.

BRIC Executive Director Jamila Owens-Todd understands the profound psychological weight old injuries carry. “Having a bullet in you is literally carrying trauma in your body,” she said. “The hospital is supposed to save your life, but they’re not necessarily in the healing business.” The clinic removes these bullets and treats old injuries, and providing physical relief but also a powerful symbolic release. “The goal is to restore a sense of agency and self-worth to those who have been victimized,” Owen-Todd said. “To heal, you have to first believe you are worthy of healing. That you have the capacity to heal.”

Conclusion

While data suggests that the fever of violence may be starting to break, statistics do not necessarily capture the day-to-day reality for many folks in St. Louis. According to a recent poll, a majority of residents still identify gun violence as the region’s most urgent problem, highlighting the gap between reality and perception. Underscoring the fragility of the city’s progress, federal funding for the OVP is set to dry up next year. While the office will continue to be funded by the city, this shift places the onus squarely on local leaders.

The question facing St. Louis is no longer if this approach works, because the evidence confirms it does. The question is whether the city has the political will to continue. For a community so thoroughly brutalized by violence, turning back now would be a form of public health malpractice—a deliberate choice to let the epidemic flare back up.