Air Pollution Will Probably Still Decline Under the Second Trump Presidency

Given President-elect Donald J. Trump’s critical rhetoric about environmental regulation, it is natural to wonder what the future of pollution reduction will look like under his next presidential term, as regulations are the primary policy mechanism by which air pollution is managed in the United States. Although it would be understandable to assume that pollution will rise, the data suggest that continued pollution abatement is the likelier outcome.

Major Air Pollutants Have Been Declining Under Each President

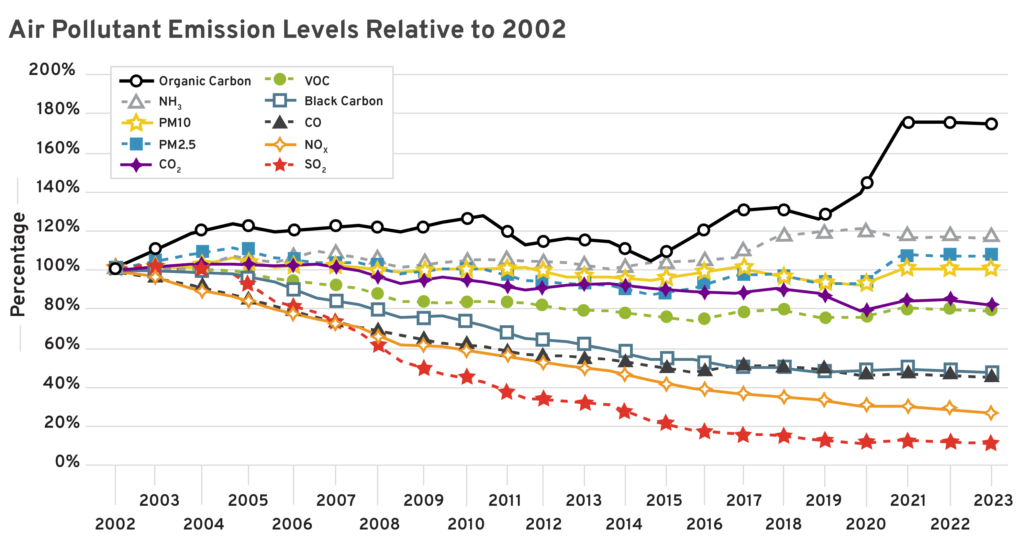

The chart below shows the pollution level of major air pollutants over the last two decades, with pollution levels indexed to 2002. With the exception of organic carbon emissions and ammonia (NH3), air pollutants have generally been decreasing.

During a second Trump term, pollutant levels will likely continue to decline on the same trajectory.

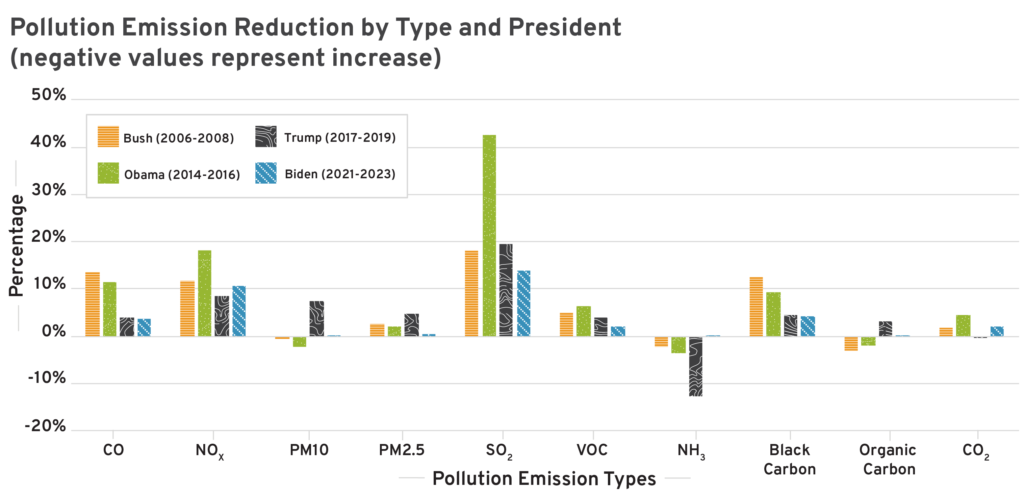

Furthermore, if we break pollution down by presidency, we see that Trump isn’t any particular anomaly in the broader trend of falling pollution levels. The chart below shows the percentage reduction in major air pollutants. For a fair comparison, each president is compared across three years of their administration, comparing the last three years of President George W. Bush’s administration, the last three years of President Barack Obama’s administration, the first three years of President Trump’s first administration (which avoids outlier pandemic data from the last year of his term), and the first three years of President Joe Biden’s administration (the only years we have data for).

Source: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and U.S. Energy Information Administration.

What we can see from this data is that, with the exception of NH3, Trump largely performed better than Biden. Obama can claim the most pollution abatement, and Bush can also claim large reductions. This is partially explained by there simply being more pollution to abate in earlier years (there are diminishing returns in pollution abatement policy), but this data also does not account for business cycles, so the variance in growth under each administration is likely another significant factor.

Overall, though, there is no apparent conclusion to draw from the data that Trump is any worse on pollution than any other president. If one president must be picked as making the least progress on pollution, it would be Biden, who had the lowest abatement rates of the four presidents for five out of the 10 pollutants.

Policy Explanation

There are three major explanations as to why pollution continued to fall under Trump and why, in some ways, his performance exceeded Biden’s. The first is that, despite Trump’s focus on regulatory reform during his first administration (like the one-in-two-out requirement for new regulation), rules focused on criteria air pollutants were largely unaffected. These regulations are promulgated under the National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) and represent a generally bipartisan approach for mitigating air pollution.

Regulatory nuance does not often make it into news articles, but the biggest regulations the first Trump administration opposed were ones that were more focused on market interventions that relied heavily on “co-benefits.” In simpler terms, the Obama administration used regulation to adopt policies that Congress would not approve, and the estimated environmental benefits of those regulations are what would have been foregone when later replaced under Trump. The most impactful regulations for improving public health, such as NAAQS, were largely unaffected.

This leads to the second major explanation, which is that regulators under the Obama administration had an incentive to overstate the effectiveness of their regulations. Because major regulations must be net beneficial to receive approval, high-cost regulations (like the Clean Power Plan) required even larger benefit estimates. One major critique of the Obama administration’s proposed regulations is that because they were often promulgated simultaneously, their benefits were being double counted. Another critique was that the Obama administration’s reliance on lower discount rates led to larger monetary benefit estimates despite no additional pollution abatement. Overall, these regulations were likely less important for overall air pollution levels than was claimed by the Obama administration, which is why air pollution still continued to fall even when Trump rolled the regulations back.

And the third major explanation is that market forces, not regulations, were already bringing about changes in economic activity that reduced pollution. Low-cost natural gas, as an example, led to the targets of the Clean Power Plan (which Trump rolled back) a decade ahead of schedule. Low-cost renewable energy, falling electric vehicle prices, and improved agriculture efficiency all shift activity away from pollution. It is well understood now that freer and wealthier economies also tend to be cleaner, and while this may be explained by their greater willingness to adopt regulation, it is also explained by the natural market incentive to maximize productivity and generate more wealth from less input (i.e., improve efficiency).

Lastly, it should be noted that a delay between policy implementation and effect is also a factor. In other words, the effect of Trump’s regulatory changes may not have been felt until the Biden years, and, similarly, Obama’s policies may have been felt most of the Trump years. But the reason this sort of explanation, while certainly true to at least some degree, isn’t a compelling case for future pollution increases is that the observed overall trend of pollution declines has been consistent across administrations. There is no major spike or drop in overall pollution levels that would indicate administration changes as the primary determinant in pollution levels.

Conclusion

While the second Trump administration will undoubtedly wade into politically fraught territory as it promotes a new vision for regulatory policy in the United States, it is important to keep critiques or praises of such policies grounded in data. It is certainly possible that changes to regulatory policy under the next Trump administration could lead to higher pollution, but that isn’t a statement that currently has any compelling evidence-based support. Ultimately, new policies will have to be evaluated on their individual merits, and broad claims about the overall environmental conditions from one president to another don’t often turn out to be true.