Reining in the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau: Practical Steps, Positive Impact

Author

Media Contact

For general and media inquiries and to book our experts, please contact: pr@rstreet.org

The CFPB would benefit from structural reform that increases congressional oversight, reduces executive authority, improves consumer protection, and enhances transparency.

Introduction

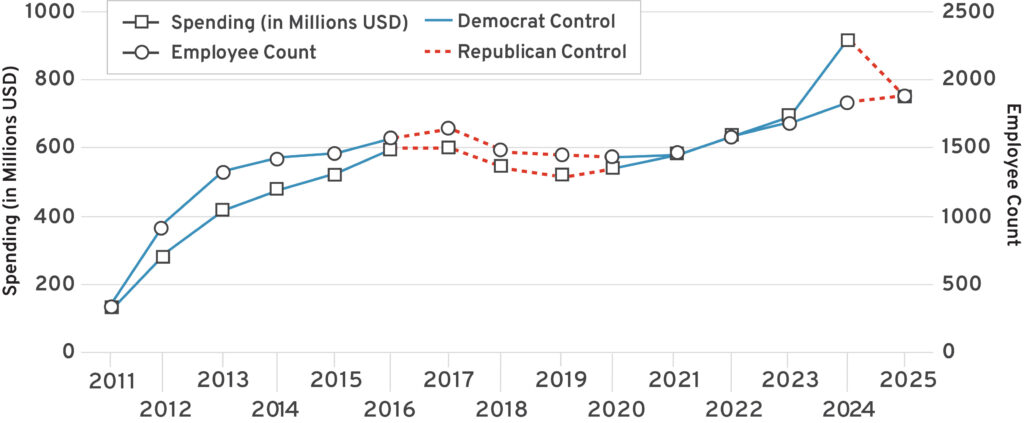

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) is a federal government agency tasked with protecting consumers from unfair, deceptive, or abusive practices by lenders, banks, and other financial institutions. Created in 2010, the agency has grown from just a few hundred employees to nearly 1,900. Its budget has also increased significantly, from $123 million in 2011 to $923 million in 2024. Due to unique statutory structures, the agency’s focus on financial institutions has shifted considerably based on its leadership. This creates policy volatility that harms consumers, financial institutions, and broader markets.

The CFPB has been criticized as a heavy-handed regulator with outsized authority, subject to politicization, and frequently aggressive in its enforcement actions. As such, structural reform is needed to increase congressional oversight, reduce executive authority, improve consumer protection, and enhance transparency. This paper explores these issues, examining the agency’s role and how it has grown, outlining examples of overuse of authority, and proposing key reforms that could help the regulator better serve its intended purpose: protecting consumers without being duplicative in its role and authority.

CFPB History, Statutory Structure, and Funding

The CFPB was created in response to the 2008 financial crisis as part of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act. During that crisis, millions of Americans lost their jobs, homes, businesses, and wealth—in part because of pervasive risky lending practices. Although other consumer protection mechanisms were already in place, Congress established the CFPB to serve as a central hub for such issues. Beyond managing consumer complaints, however, the agency was given extraordinary power for civil proceedings against financial institutions and subsequent consumer restitution. The agency is tasked with enforcement under the statutorily defined standard of “unfair, deceptive, abusive acts and practices” (UDAAP). It is led by a sole director for a five-year term—now removable at will, though previously removable only for cause.

The agency is funded through the Federal Reserve, outside of congressional appropriations. It was established with the authority to request up to 12 percent of the Federal Reserve’s operating expenses, although this was recently reduced to 6.5 percent under the One Big Beautiful Bill Act. Importantly, the Dodd-Frank Act does not mandate comprehensive cost-benefit analyses for the CFPB; instead, the agency must only “consider” negative externalities of proposed rules.

The Rapid Growth of the CFPB

The CFPB has expanded substantially since its inception. Annual spending has risen from $123 million in 2011 to $923 million in 2025—a 650 percent increase—and the number of employees has grown by more than 500 percent from 343 in 2011 to approximately 1,900 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: CFPB Expansion in Spending and Staffing, 2011 to 2025

https://www.congress.gov/crs_external_products/R/PDF/R48295/R48295.8.pdf.

This growth has continued largely unchecked because the agency’s funding mechanism significantly limits congressional oversight. Not only is the CFPB funded outside of congressional appropriations but its funding source, the Federal Reserve, is outside of this system as well. This “double insulation” gives the CFPB an unusual level of financial independence.

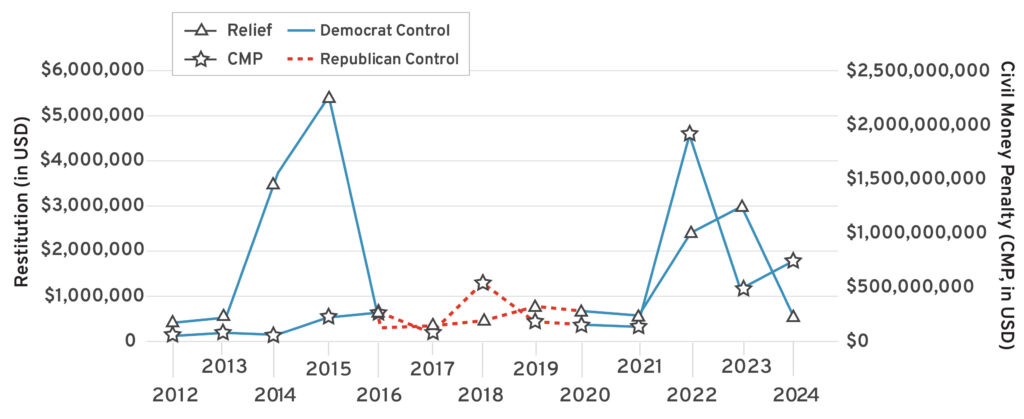

Additionally, the CFPB retains money from the fines and enforcement penalties it metes out, which are placed in its Civil Penalty Fund. The agency primarily uses these funds for consumer restitution. The Civil Penalty Fund has expanded and contracted in tandem with the agency’s varied use of authority over time, in alignment with the political party in power at the time (Figure 2).

Figure 2: The CFPB’s Civil Penalty Fund, 2012 to 2024

https://www.congress.gov/crs_external_products/R/PDF/R48295/R48295.8.pdf.

Taken together, these figures point to a trend of expansion of the CFPB during Democratic administrations and contraction during Republican ones—a pattern that supports the view that the agency is swayed by political winds. In fact, much of the backlash the agency has experienced under the current administration is in response to a perceived overuse of authority during the former administration.

Overuse of Executive Authority

The CFPB has leaned heavily on broad, loosely defined UDAAP standards and advanced rules via informal guidance or enforcement rather than formal rulemaking (Table 1). Many negative effects have stemmed from these excessive enforcement actions, including corporate closures and consolidations that have reduced competition and allowed larger players to gain market share—potentially reducing access to financial services for consumers.

Table 1: Examples of CFPB Overreach

| Year | Action | Issue | |

| Discrimination Bulletin | 2022 | Expanded “unfair” to include discrimination | Statutory overreach, out-of-statutory scope |

| Credit Card Late Fee Rule | 2024 | Capped credit card late fees at $8 | Overstepped statutory authority by imposing fee caps beyond explicit congressional mandate |

| Overdraft Fee Rule | 2024 | Capped overdraft fees at $5 | Demonstrated regulatory overreach by setting fee caps that interfere with market pricing without clear statutory basis |

| Buy Now, Pay Later (BNPL) Rule | 2024 | Applied Truth in Lending Act regulations to BNPL lenders | Challenged for classifying BNPL as credit card providers without explicit congressional authorization |

| Medical Debt Rule | 2025 | Removed medical debt from credit reports | Courts ruled that the CFPB exceeded its authority under the Fair Credit Reporting Act, lacking clear rulemaking power |

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, March 22, 2022. https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/cfpb_

bulletin-2022-05_unfair-deceptive-acts-practices-impede-consumer-reviews.pdf;

“Credit Card Penalty Fees (Regulation Z),” Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, 2024. https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/cfpb_credit-card-penalty-fees_final-rule_2024-01.pdf; “Overdraft Lending: Very Large Financial Institutions,” Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, 2024. https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/cfpb_overdraft-final-rule_2024-12.pdf; “Prohibition on Creditors and Consumer Reporting Agencies Concerning Medical Information (Regulation V),” Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, 2025. https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/cfpb_med-debt-final-rule_2025-01.pdf; “Use of Digital User Accounts to Access Buy Now, Pay Later Loans,” Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, May 31, 2024. https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/cfpb_bnpl-interpretive-rule_2024-05.pdf.

Notably, none of these rules underwent a comprehensive cost-benefit analysis, and several have since been rescinded through litigation, the Congressional Review Act (CRA), or other means. This is problematic because the implementation and subsequent rescission create uncertainty for financial institutions and confusion for consumers. In addition, there is no reliable way to track the extent to which consumers continue to act based on rescinded rules— a negative externality of the CFPB’s ability to impose sweeping changes with relatively low procedural barriers.

Reform Measures: Practical Steps, Positive Impact

While the described issues may be wide-ranging and complex, the majority of the problems that stem from the CFPB are tied to its outsized powers among federal regulators and its lack of congressional oversight. To address these structural and operational shortcomings, this section outlines a series of targeted reforms that would help improve oversight, reduce politicization, and enhance consumer protection. Each recommendation offers a practical path toward curbing the agency’s excesses while preserving its ability to fulfill its core mission. These measures provide policymakers with a range of options—from incremental adjustments to comprehensive restructuring—to strengthen the agency’s accountability and stability.

1. Dismantle the Double-Insulated Funding Structure

Because the CFPB’s unusual funding model limits congressional oversight, reforming its budget process is critical to improving transparency and accountability.

Since the CFPB’s inception, policymakers have questioned the agency’s funding structure. However, in the 2024 legal challenge CFPB v. Community Financial Services Association, the Supreme Court upheld the structure as constitutional. In this case, the Court ruled that because Congress wrote the law that created the structure, only Congress could change it.

Thus, the most direct path to making funding-structure changes that would increase oversight and reduce politicization would be through legislation like Rep. Andy Barr’s (R-Ky.) Taking Account of Bureaucrats’ Spending Act, which would shift CFPB funding to congressional appropriations. Alternative options include imposing funding caps with congressional approval for increases. Although the One Big Beautiful Bill Act did reduce the maximum allowable draw from the Federal Reserve from 12 percent to 6.5 percent, it remains a sizable budget that still lacks direct oversight.

2. Modify Leadership to a Board Instead of a Sole Director

A multi-member leadership structure could reduce political swings and ensure more stable, consensus-driven decision-making at the CFPB.

Former CFPB directors have been criticized for politicized rulemaking and excessive use of authority. Had these directors been subject to the approval of a multi-member commission as opposed to having sole authority, many of the more excessive changes under the agency might have been avoided, reducing regulatory confusion among financial institutions and consumers.

The CFPB is one of only a few independent agencies (including the Federal Housing Finance Agency and Office of the Comptroller of the Currency) that operate under a sole director. But given the agency’s other insulations, it is unique among federal agencies in its ability to radically transform consumer-focused financial regulatory policy with almost no oversight.

Given this unchecked authority, it is likely that legislation to move from a sole director to a multi-person commission would garner bipartisan support. One such bill, the Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection Commission Act, was introduced in July 2025 by Rep. Bill Huizenga (R-Mi.) to propose changing the CFPB from a sole director to a five-person commission.

3. Narrow the Definition of UDAAP

Clarifying statutory definitions would reduce the agency’s ability to expand its mandate through broad or inconsistent interpretations.

CFPB directors have been able to claim a significant amount of power through their interpretation of the UDAAP standard under which the agency operates. An additional bill from Rep. Barr, the Rectifying Undefined Definitions of Abusive Acts or Practices (Rectifying UDAAP) Act, was introduced in February 2025 to close this loophole by defining abusive acts or practices more clearly, requiring that an act be intentional, materially interfere with consumers’ ability to understand terms, or take advantage of consumers’ lack of understanding. The bill would also prohibit the CFPB from considering discriminatory practices, as it lacks statutory authority to do so. According to proponents of the bill, discriminatory practices are already illegal and therefore do not need to fall under the CFPB’s purview. This stance has also been upheld in a recent court case, but other issues with the UDAAP standard remain.

Rectifying the UDAAP would limit the agency’s ability to be as interpretive in its rulemaking, thus reducing its politicization.

4. Require Cost-Benefit Analyses

Subjecting CFPB rulemaking to rigorous cost-benefit reviews would help safeguard against regulations that impose high costs without delivering clear consumer benefits.

Unlike most other financial regulators, the CFPB is not required to complete cost-benefit analyses for its rulemaking. Instead, it is only statutorily obligated to “consider” the effects of proposed rulemaking. The CFPB should be required to conduct rigorous cost-benefit analyses for its rules to ensure that they do not unintentionally reduce access to financial products, raise costs, or stifle innovation. This requirement could be implemented through a legislative amendment to the Dodd-Frank Act mandating that CFPB follow Office of Management and Budget guidelines for regulatory impact analysis similar to those required of other federal agencies. These analyses should also be published to improve accountability and allow for informed public comment.

5. Serve as the Consumer Hub for Financial Fraud and Scams

The CFPB could better focus its role in protecting consumers from the growing threat of financial fraud and scams.

Financial fraud and scams against consumers continue to be a pervasive issue. Federal Trade Commission data estimate $12.5 billion in reported losses in 2024, and the Government Accountability Office suggests that actual losses may be much higher because of underreporting and a fragmented federal approach.

Given that the CFPB is tasked with protecting consumers, the agency is well-suited to address the consumer side of fraud and scams by serving as a central database and resolution center—receiving scam reports, routing consumers to the right channels, and maintaining a database for potential restitution. In addition, because the CFPB engages in civil, not criminal, enforcement, the agency should coordinate with the Department of Justice and other agencies. Expert suggestions for ensuring consumer uptake include a public-facing portal (e.g., scams.gov) and awareness campaigns.

6. Dismantle the Agency

For those seeking more significant change, eliminating the CFPB and redistributing its functions would be the most far-reaching method for preventing the risk of future overreach.

Some critics of the CFPB argue that its functions are duplicative and could easily be absorbed into other financial regulatory bodies, as was done before its existence. They propose eliminating the agency and redistributing its responsibilities, thereby reducing the “regulatory pendulum” effect that often occurs between administrations. This would also be in line with the current administration’s broader push for financial deregulatory policies and streamlining efforts.

Conclusion

The CFPB wields significant authority with limited oversight. Reforms—from leadership changes to funding restructuring—could depoliticize the agency, reduce regulatory whiplash, and improve consumer protection. While some argue for elimination, any substantial change requires congressional action. The bipartisan appeal of reducing extreme policy swings could provide a rare opportunity for durable reform.