Coalition raises concerns about the Copyright Claims Board

Comments of Re:Create et al.

In re Docket No. 2025-2: CASE Act Study

The undersigned organizations represent a broad cross-section of stakeholders dedicated to balanced copyright and a free and open internet, including libraries, civil libertarians, online rights advocates, start-ups, consumers, and technology companies of all sizes. We write to share our perspectives on the Copyright Claims Board (CCB), to inform your inquiry into its effectiveness after more than two years in operation. As discussed in more detail below, we are concerned that the CCB is a venue where most claims are dismissed, the remaining claims are decided mostly by default, and in the end the payouts to intended beneficiaries over the course of the last two years (~$75,000) amount to barely more than 1% of the agency’s budget for those years (~$5.4 million).[1] If these trends continue, Congress should consider repealing the CASE Act.

Origins of the CCB

The idea of a small claims process for copyright was debated for years prior to the passage of the CASE Act, including in a report prepared by the Copyright Office[2] as well as in legislative hearings and debates in the Senate and House of Representatives. Throughout these discussions, it was clear that the copyright community was divided over the proper contours of a small claims process, and in particular over the merits of the CASE Act approach. Critics, including Re:Create and its member organizations, expressed a wide variety of concerns with the CASE Act’s version of small claims, from Constitutional infirmities to the potential for abuse of the system by trolls and cranks.[3] Perhaps due to the disagreements in the copyright community, the CASE Act wasn’t passed as a stand-alone bill. However, it was signed into law as a last-minute appendage to a massive omnibus COVID Relief package, a classic must-pass “Christmas Tree” bill that was signed into law by President Trump on December 27, 2020.

Perhaps this study will offer the Copyright Office, Congress, and the copyright community an opportunity to reflect on what can go wrong when a major policy is passed over strenuous objections from key stakeholders. In this case the federal government has spent millions of dollars to build and sustain an agency that spends most of its resources patiently catering to invalid claims, deciding just a handful of cases over two years, and paying out barely $75,000 to intended beneficiaries. Since the paucity of valid claims appears to result primarily from the complexities of copyright law itself and the most basic requirements of due process, the prospects for improving the Board’s efficacy by changing the Board itself are dim.

Almost Every CCB Claim Is Dismissed

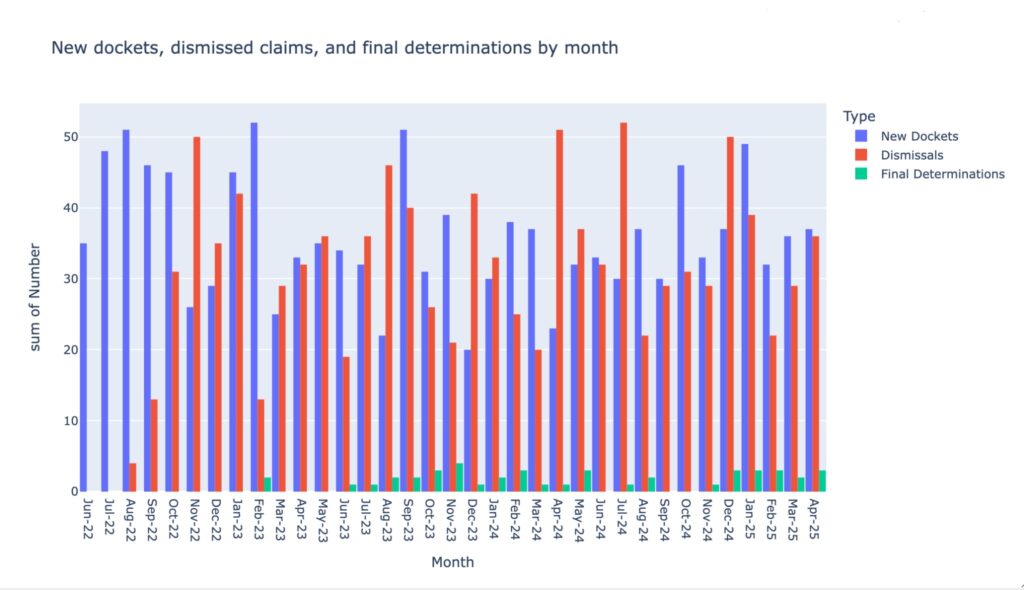

The vast majority of claims filed with the Copyright Claims Board are dismissed, that is, they do not reach a final determination on the merits. The CCB’s statistical summary says that of the 1,222 cases filed between June 2022 and March 2025, only 35 (~3%) had reached final determinations.[4] The bar graph below,[5] based on data from the CCB’s online filing system, shows new claims filed, claims dismissed, and final determinations on the merits for each month since the CCB was created. After an initial ramp-up period, each month the Board seems to be dismissing approximately the same number of claims as it takes in; sometimes the Board dismisses more claims than it takes in (last April there were twice as many claims dismissed as filed), and occasionally the filed claims surpass the dismissals, but the gestalt is clear: the CCB is mostly churning through non-compliant claims. Note that each docket can contain up to three versions of a claim (an original claim and two attempts to amend), so that the chart doesn’t fully represent how many claims, as distinct from claimants, the CCB staff attorneys must process in a given month. The tiny green blips at the bottom represent the handful of cases each month that merit actual final determination from the Board.

Most Dismissed Claims Have Substantive Flaws

Significantly, the data suggest that the procedural requirements of the CCB are not the main drivers of claim dismissal. Substantive deficiencies are cited far more often than procedural ones. Of the possible reasons a claim can be dismissed, the most common category (representing 36% of dismissals) is “failure to amend,” meaning that a staff attorney at the CCB reviewed a claim, informed a claimant that their filing was non-compliant, and the claimant did not file an amended complaint.[6] These Orders to Amend include detailed descriptions of the claim’s deficiencies and instructions for curing the claim. Claimants have two opportunities to amend their complaints to bring them into compliance. The most common reasons given by staff attorneys for finding claims non-compliant are substantive, i.e., they deal with whether the claim states sufficient facts to allege a basic case of copyright infringement against a qualifying defendant.[7] Substantial similarity, access, legal or beneficial ownership, and similar issues predominate. Claimants are simply not making a case for copyright infringement, leaving the Board no choice but to request amendment. Another 7% of claims are dismissed after two attempted amendments still don’t result in a compliant claim, and a combined 4% are rejected due to bad faith by the claimant or a Copyright Office refusal to register the work at issue – also signs of substantive weakness in the claim.

By contrast, the only procedural hurdles that represent a substantial number of dismissals are the requirement to file a proof of service (cited in 17.3% of the dismissed claims) and respondent opt-outs (representing 11.2% of dismissals). These are due process requirements without which the CCB would be glaringly unconstitutional.

Statistics released by the CCB paint a similar picture.[8] Of the 999 claims that had been processed as of April 2025, 470 had been dismissed as noncompliant and 187 had failed to show proof of service. Of the remaining matters, only 14 reached a final, substantive decision. In 21 cases, claimants prevailed due to respondent default.

To answer some of the questions posed in this inquiry, these numbers suggest that:

● The $40 filing fee is not high enough to deter frivolous claims. Hundreds of non-compliant claims are filed each year by claimants who disappear after a CCB Staff Attorney spends substantial time evaluating the claim and preparing a detailed Order to Amend.

● The compliance review process is working well to screen out invalid claims. Claimants do not appear to be converting very many of the initially invalid claims to valid ones, but it is unclear whether there are valid claims behind these initially invalid filings. It is also unclear what the CCB could do to improve the situation, in addition to the detailed feedback and instructions it already provides in its Orders to Amend.

The Proportion of Final Determinations by Default Is Cause for Concern

In the debates over the CASE Act, critics raised concerns about the possibility that some respondents in CCB claims may not understand this new tribunal or take notices about proceedings there seriously. According to the CCB’s published statistics, 21 of the 35 final determinations in CCB cases as of April 2025 were default judgments.[9] Thus, 60% of cases that reached a decision were decided in favor of the claimant[10] because the respondent did not participate. This is in stark contrast to copyright claims brought in federal court, which end in default only 7% of the time, a proportion that Lex Machina characterized as “high” compared to other types of claims.[11] The high proportion of default judgments among final CCB determinations may suggest shortcomings in the opt out mechanism, as respondents who understood the nature of the CCB and the consequences of their non-participation might have been expected to opt out of the proceeding rather than subject themselves to its jurisdiction knowing they would forfeit the case.

It is difficult to know why parties decline to participate in CCB proceedings, either by defending themselves or by opting out. In one case, however, a respondent who missed the opt out deadline, Angel Jameson, subsequently joined the proceeding and expressed repeatedly and unequivocally that she did not want to participate in the CCB’s proceedings.[12] Jameson’s objections exemplify the concerns of CASE Act critics. According to the Board’s final default determination, Jameson expressed “disbelief that the Board is a government tribunal” and demanded “an ‘official day in court.’”[13] Because Jameson missed the opt out deadline, the CCB awarded the claimant $4,500 in damages, rejecting Jameson’s request to vacate the judgment.

The Copyright Office, the CCB, and Congress should keep a close eye on the CCB’s docket and the number of cases decided by default. Damages in cases determined by default have average damages amounts (~$4400) more than double those in contested final determinations (~$2000). The Jameson case suggests that it is possible for respondents to fail to opt out due to mistrust and misunderstanding of the CCB process. The CCB is extraordinarily patient and helpful to claimants who fail to submit compliant claims, offering them detailed feedback and two opportunities to amend initially flawed filings. Respondents should receive a similar degree of assistance before they are bound to pay default judgments.

The CCB’s Jurisdiction Should Not Be Expanded

The NOI asks several questions about whether and how the CCB’s jurisdiction could be expanded, to cover other claims arising under Title 17, more types of works, or the capacity to award more or different kinds of damages. There is no reason to consider adding to the CCB’s docket or to its powers until it can be established that the CCB is capable of accomplishing its initial mandate. At present, the CCB appears to be drowning in frivolous claims, handing out a handful of default judgments to facially valid claims with only one party present, and slowly grinding away at a handful of disputed claims.

CONCLUSION

The startup and operating costs of the CCB for its first two years of operations was around $5.4 million. It has disposed of around 1000 claims, mostly by dismissing them, issuing final resolution in just 35 cases,[14] with an average damages award across all final determinations of around $2,600. That means American taxpayers have spent around $5,500 per case to reject hundreds of frivolous claims, adjudicate the remaining 3.5%, and issue opinions awarding damages that on average amount to less than half the cost of processing the claim. This experience has belied the CASE Act supporters’ fundamental contention, that copyright holders with valid “small claims” will rush to take advantage of such a venue. If these trends continue, Congress should consider repealing the CASE Act.

Sincerely,

Association of Research Libraries

R Street Institute

See the original letter below:

[1] According to CCB statistics, 99 claims were settled outside of the CCB process. Key Statistics, Copyright Claims Board, https://www.ccb.gov/CCB-Statistics-and-FAQs-April-2025.pdf. The financial terms of those settlements, if any, are not generally published, and it is unclear what role the CCB plays in encouraging settlement of claims.

[2] U.S. Copyright Office, Copyright Small Claims (2013), https://www.copyright.gov/docs/smallclaims/usco-smallcopyrightclaims.pdf.

[3] See, e.g., Re:Create, The Case Against the CASE Act: What You Need to Know, Oct. 21, 2019, https://www.recreatecoalition.org/the-case-against-the-case-act-what-you-need-to-know/ (listing objections and linking to critical statements from other groups).

[4] Key Statistics, Copyright Claims Board, https://www.ccb.gov/CCB-Statistics-and-FAQs-April-2025.pdf.

[5] Unless otherwise noted, statistics in these comments are based on “Aggregate data about claims filed with the Copyright Claims Board,” https://bibliobaloney.github.io/#about (last visited April 30, 2025). The bar graph is taken directly from CCB Aggregate Data. According to the site, its data was last refreshed from the eCCB docketing system on April 25, 2025.

[6] See CCB Aggregate Data – Dismissed cases, https://bibliobaloney.github.io/#closed.

[7] See CCB Aggregate Data – Orders to Amend, https://bibliobaloney.github.io/#otas.

[8] See Key Statistics, Copyright Claims Board, https://www.ccb.gov/CCB-Statistics-and-FAQs-April-2025.pdf.

[9] Id.

[10] With two notable exceptions, in which the Board rightly recognized that the claimant had not demonstrated that the respondent was the appropriate entity to be held liable for the alleged infringement. See Jonathan Bailey, Copyright Claims Board Rules in Favor of Defaulting Party, Plagiarism Today, Feb. 10, 2025, https://www.plagiarismtoday.com/2025/02/10/copyright-claims-board-rules-in-favor-of-defaulting-party/ (describing the Board’s decision in Sommet v. Pleasure in Life LLC); Authors Alliance, A Copyright Small Claims Update: Defaults and Failure to Opt Out, Authors Alliance, Feb. 1, 2024, https://www.authorsalliance.org/2024/02/01/a-copyright-small-claims-update-defaults-and-failure-to-opt-out/ (describing the Board’s decision in Joe Hand Promotions, Inc. v. Dawson, et al).

[11] Lex Machina, Copyright and Trademark Litigation Report 2021 at 21 (June 2021), https://pages.lexmachina.com/rs/098-SHZ-498/images/Lex_Machina_Copyright_and_Trademark_Litigatio n_Report_2021.pdf.

[12] See Oakes v. Heart of Gold Pageant System Inc., et al, No. 22-CCB-0046, Final Determination.

[13] Id. at 4.

[14] Key Statistics, Copyright Claims Board, https://www.ccb.gov/CCB-Statistics-and-FAQs-April-2025.pdf.

[15] Not every member of the Re:Create Coalition necessarily agrees on every issue, but the views we express represent the consensus among the bulk of our membership.