Rebuilding the Force: Solving Policing’s Workforce Emergency

Authors

Table of Contents

- Executive Summary

- Introduction

- The Thinning Blue Line

- Hiring for a Job Like No Other

- The High Cost of Low Standards

- Key Recommendations

- Conclusion

- Appendix 1: Federal Recruitment and Retention Legislation

- Appendix 2: Notable State Recruitment and Retention Legislation

Media Contact

For general and media inquiries and to book our experts, please contact: pr@rstreet.org

The future of law enforcement depends on its ability to adapt to evolving societal expectations and labor market dynamics.

Executive Summary

This policy study explores the recruitment and retention crisis in U.S. law enforcement, analyzing historical, social, and economic factors that have shaped the problem. It describes the staffing shortage, evaluates its consequences, and explores innovative strategies to address the issue. The findings and recommendations offered in this paper provide a practical, comprehensive framework for agencies to build and sustain a strong, resilient workforce.

Introduction

Despite growing public demand for police services, departments across the United States are losing officers faster than they can hire new ones. This alarming trend reflects broader societal challenges, including shifting demographics, collapsing institutional trust, and changing attitudes toward work. Strong economic and employment conditions have put law enforcement agencies in competition, not only with one another for talent but also with private-sector companies that offer higher salaries. Although the police workforce crisis is not the sole cause of actual and perceived increases in crime in the past five years, it has been a contributing factor.

This labor-market challenge calls for bold, market-based policy ideas, a higher caliber of scholarship, and solutions that go beyond surface-level fixes. In this policy study, we assess the state of the law enforcement labor market, analyze the key factors driving this crisis, and examine why it has become increasingly difficult to recruit and retain officers. We also highlight innovative strategies that go beyond short-term hiring incentives, focusing on long-term workforce development, retention policies, and structural reforms that can make policing a viable and attractive career for the next generation. The paper concludes with a summary of key recommendations designed to help agencies build and sustain a strong, resilient, and capable workforce.

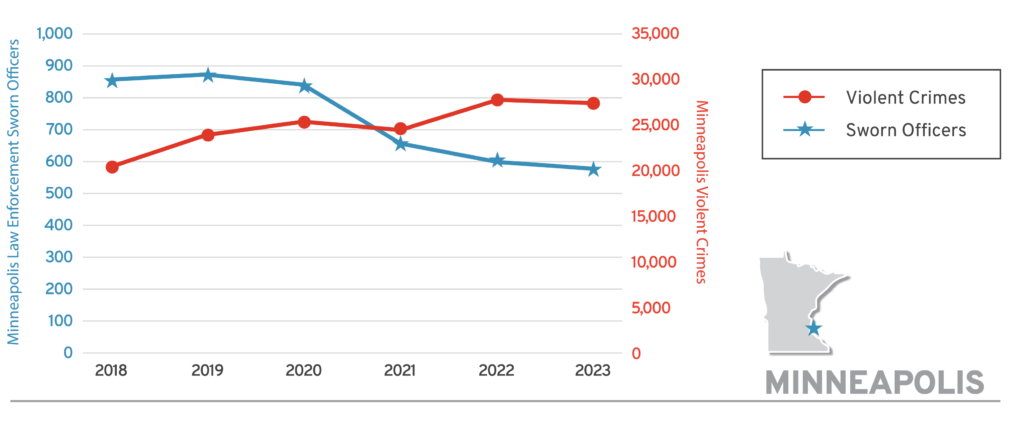

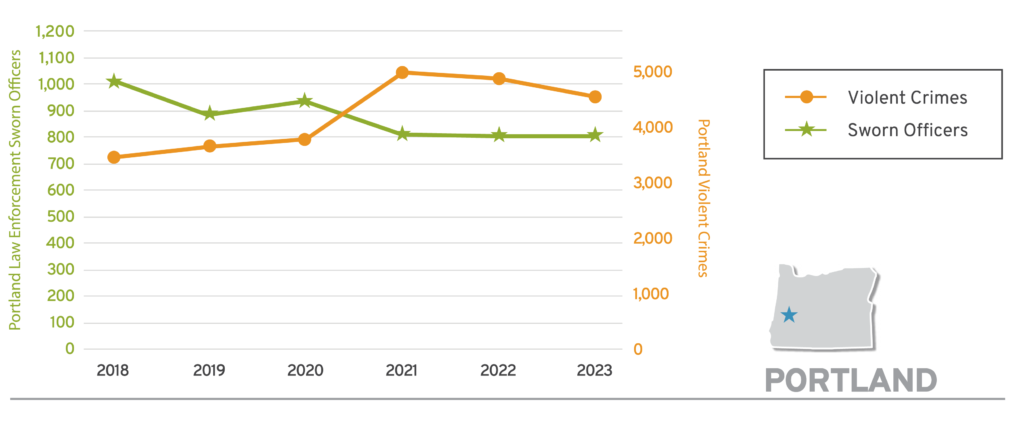

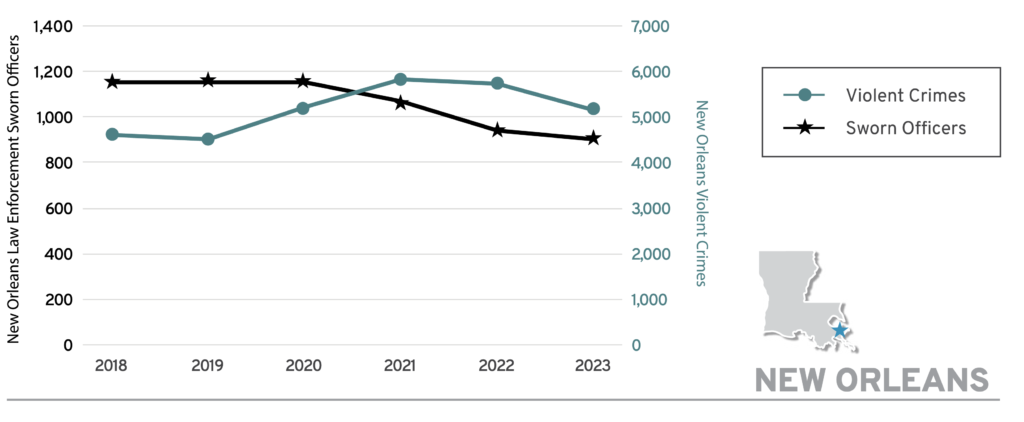

The Thinning Blue Line

The law enforcement labor shortage is doing what the “defund the police” movement could not—hollowing out U.S. law enforcement. A 2024 survey found that 70 percent of agencies reported having more difficulty hiring compared to five years ago. Dozens of the nation’s largest departments have shrunk by 10 percent or more. Some agencies have seen staffing levels plummet dramatically, such as New Orleans and Minneapolis, which are both 40 percent smaller than they were a decade ago. The New York City Police Department (NYPD) has also seen historically high attrition, bringing on just 2,345 new recruits last year, hundreds short of the 2,931 officers who left. The NYPD continues to bleed about 200 police officers per month. Even in cities where the exodus has been less pronounced, like Chicago and Philadelphia, department budgets have been strained by excessive overtime and expensive recruiting campaigns. For decades, cities and states have been asking their police to do more and more with fewer resources, which may correlate with increases in crime (Figure 1).

Figure 1: A Tale of Three Cities: Law Enforcement Staffing Levels vs. Crime Rate

Sources: “Law Enforcement Employees Reported by the United States,” FBI Crime Data Explorer, last accessed Feb. 12, 2025. https://cde.ucr.cjis.gov/LATEST/webapp/#/pages/le/pe; “Police Strategic Plans and Annual Reports,” Portland.gov, last accessed Feb. 12, 2025. https://www.portland.gov/police/chiefs-office/ppb-plans-and-reports; New Orleans Police Department “NOPD Staffing Dashboard,” City Council New Orleans, last accessed Feb. 18, 2025. https://app.powerbi.com/w?r=eyJrIjoiYTllMzIyZTMtY2JiYS00YTQyLWFkY2EtZTVkYjRiMDFhMmQ4IiwidCI6IjFkYzNlZmNmLTVlMTQtNGRkNS1iMjE3LWE3NTBjNWIxMzIyZCIsImMiOjN9&pageName=ReportSection21e91234a747587e452f.

Public Perception

One popular explanation for the declining law enforcement workforce is that high-profile incidents of police violence have tarnished the profession’s image to such a degree that people no longer want to serve. This explanation has its roots in the “Ferguson Effect,” a theory positing that criticism of police since 2014 has not only led to apathetic enforcement and subsequent spikes in crime but also recent surges in retirements and resignations. The mayor of Tulsa, Oklahoma, explained, “the national dialogue that demonizes police officers has made police department staffing significantly more difficult for every major city in America.” Most police chiefs agree: 78 percent of departments identified negative public perception as a significant barrier to recruitment. Although this may be a factor, recent evidence suggests that the Ferguson Effect has been less pronounced than once believed.

Policing Trends

Law enforcement is a high-stress profession, and officers are frequently exposed to traumatic events and physical danger. Accountability measures, like state-mandated use-of-force policies, have been perceived by some as limiting agency autonomy. Additionally, officers perceive the job as riskier than ever before, and evidence suggests that they are correct. From 2021 to 2023, 194 officers were killed in the line of duty—more than any other consecutive three-year period in the past 20 years. Officers are now three times more likely to suffer a nonfatal injury than any other class of worker. Moreover, studies have shown that chronic stress and burnout are leading causes of early retirements and resignations among officers. The demands of the job come at a high cost: The life expectancy of former police officers is 21 years shorter than the average American’s.

Demographics

The movement away from manufacturing toward a service-based, knowledge economy has reshaped our society. In 2020, millennials overtook baby boomers as America’s largest generation—a profound shift in the workforce with implications in every sector and industry. In fact, over the next five years, an exodus of baby boomers will reduce the overall number of Americans in the labor market, creating a “silver tsunami” and intensifying competition for workers. If law enforcement agencies do not take proactive steps to mitigate these generational workforce shifts, a potentially dangerous imbalance could form in many agencies between the number of experienced officers and new recruits.

Economics

Like any market, the law enforcement labor market is governed by supply and demand. Right now, demand for police officers is higher than ever, but the supply of appropriate candidates is getting smaller. At any given moment, the employer–employee power dynamic is a product of the market economy. During economic downturns or recessions, fewer jobs are available for workers, giving employers more options and control over employees. Conversely, when the economy is booming, employees have more opportunities and therefore greater control than employers. With historically low unemployment rates and the last sustained recession a distant memory, American workers are currently in the driver’s seat. It should therefore come as no surprise that $50,000—the average starting salary of an officer in the United States—is insufficient compensation for one of society’s most demanding jobs. Inflation has exacerbated the problem in urban areas where the cost of living is high and additional officers are most desperately needed.

Hiring for a Job Like No Other

Law enforcement is not like other careers. Any other job with such a long list of duties, irregular hours, and inherent dangers would demand a premium in the marketplace. However, entry-level officers typically earn less than comparable college graduates and much less than job seekers with degrees in engineering, medicine, or finance. A 2024 survey found that most college students are not interested in becoming police officers, particularly those with higher grade point averages. Especially in this post-COVID period of transitional labor relations, characterized by remote work and employee choice, it is not surprising that police are feeling left out.

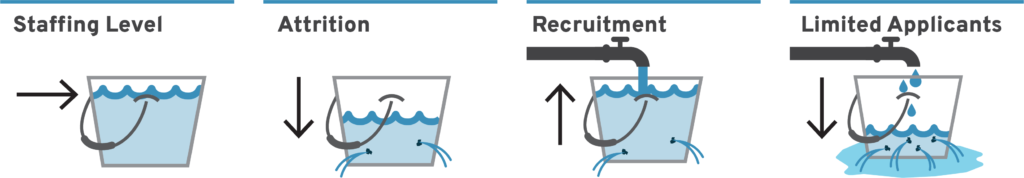

Sidebar: The Labor Bucket: Researchers have used a bucket metaphor to describe the law enforcement labor market. In this analogy, the bucket represents the total need for officers, and the water level indicates the current staffing level. Officers “leak out” through retirements or resignations, causing the water level to drop. The bucket is continually refilled through recruitment, but if the flow of new officers into the bucket is weak because of limited applicants, water flows out of the bucket faster than it can be refilled. Furthermore, as community policing expectations broaden the duties police are expected to perform, the size of the bucket must grow to accommodate those new demands, requiring more “water” to fill it. In other words, police HR departments face a “three-body problem.” Agencies must dynamically balance a triad that includes hiring, workforce attrition, and the expansion of police duties—constantly shifting variables that affect each other in unpredictable ways.

Call of Duty

Most police officers join the force for reasons that go beyond salary. When asked why they chose policing as a career, many officers will offer some version of “I want to help people.” Police departments are public service organizations, so it makes sense that they would attract people interested in serving the public. The best law enforcement recruiters recognize this and lean into that core value with messaging that reinforces how officers are serving a greater purpose than themselves. Offering people a sense of meaning is essential when marketing a tough, dangerous job that does not pay particularly well. Even though the salary, benefits, and working conditions are often superior elsewhere, intrinsic benefits will always naturally attract certain people to law enforcement.

Generation “Job-Hop”

Law enforcement leaders are also increasingly being tasked with accommodating the needs and expectations of officers from different generations. Gen Z has been described as a cohort of pragmatic, tech-savvy individuals who value direct communication and self-care—attributes that are often lacking within police culture. The demanding schedule of a rookie cop can be a particularly significant roadblock for younger workers, who tend to prioritize flexibility and work/life balance. In general, young people also have less organizational commitment than prior generations and are much less likely to stay in the same job their entire career. Once considered a red flag on a resume, new research suggests that job hopping can yield knowledge and skills that enhance employability. Furthermore, the higher levels of illicit drug use, obesity, and debt seen in younger generations have led to marked reductions in the available pool of qualified applicants.

For younger employees, boredom is the enemy. A dynamic, varied workday is more important to current labor market participants than it was to previous generations. Strategies such as job enrichment (making work more meaningful), job enlargement (adding more responsibilities), and job rotation (temporarily mixing up assignments) can help keep officers motivated and refresh their skills. Forward-thinking agencies are restructuring job descriptions and organizational charts to improve flexibility and offer more scheduling options. The rigid hierarchies and inflexible schedules of the past are being overhauled to appeal to a new generation of workers, most of whom do not plan to stay in the same job for decades.

Good Cops Know Good Cops

When police search for a suspect, the task is not given to just one person—it is a group effort involving other patrol units and sometimes other departments. Recruiting should work the same way. Employee referral systems make every officer a potential recruiter. Many departments reward officers for successful referrals with a “finder’s fee” bonus, like time off or cash. Having learned about the agency firsthand from an officer, referred candidates have a more realistic view of the job. Even as websites like LinkedIn and Indeed have made it easier to recruit online, candidates discovered via crowdsourced, informal avenues are more likely to be hired and stay longer. When leaders make recruitment and retention a top priority for everyone in the organization, the results speak for themselves.

Trust Is Earned, Not Given

With confidence in police at a record low, rebuilding public trust will be necessary to make law enforcement careers more appealing. One advantage police have over other employers is frequent access to news outlets. Recruiters can leverage relationships with reporters into “earned media” publicizing new recruitment programs or hiring incentives. These types of human-interest stories are a good way to bring attention to police departments and advertise career opportunities. Sharing use-of-force data and other law enforcement information is another way to help communities understand how they are being policed. Departments can also designate “recruitment liaisons” as an outreach strategy to build personal connections and listen to community concerns. These types of partnerships, particularly with churches and religious organizations, can help break down barriers and garner credibility with communities historically skeptical of the police.

Streamlined Hiring

Because a protracted, cumbersome hiring process can deter potential recruits, once a candidate is in the door, it is important to expedite interviews and hiring. This is not only about speed but also about making the process applicant- friendly with online applications, revamped testing requirements, and interim employment opportunities. Pre-hire programs start recruits in civilian roles while they wait for academy slots, keeping them engaged and reducing drop-off. Departments should also consider conducting entry interviews to learn why candidates are joining the force, as these can be just as insightful as exit interviews. Hiring managers should also explore and leverage grant funding available through the Recruit and Retain Act, which can help cover costs related to sign-on bonuses, childcare services, relocation assistance, tuition reimbursement, and more (see Appendix 1 for relevant federal legislation).

The High Cost of Low Standards

Not everyone is cut out to be a law enforcement officer. Recruiters are looking for a specialized combination of traits that limit the supply of qualified candidates. Specifically, the ideal officer is:

- Courageous enough to put their life on the line at work every day

- Knowledgeable of most federal, state, and municipal laws

- The right temperament to wield power in a responsible way

- Comfortable around firearms

- Able to run a mile at a full sprint

At a moment’s notice, officers must be able to serve as social workers, conflict mediators, mental health counselors, medical responders, information technology experts, traffic controllers, counter-terrorism units, and paralegals—sometimes all in the span of a single shift. It is a demanding career by almost any definition. Even if municipalities could afford to pay their officers a premium rate, finding enough candidates who embody all of these qualities constrains the candidate pool. To get more people in the door, cities like New York and Chicago have been forced to lower hiring standards. This is a mistake.

The tragic case of Sonya Massey underscores the deadly consequences of letting standards slip. In July 2024, the 36-year-old resident of Springfield, Illinois, called 911 to report suspicious activity outside her home. Instead of receiving help, she was killed—shot three times by an Illinois Sheriff’s Deputy with a long record of misconduct. Before the shooting, he had been transferred or dismissed from six police departments during his brief stint in law enforcement. His record also included two convictions for driving under the influence, leading to his discharge from the military for serious misconduct.

The case is a reminder that lowering hiring standards to boost recruitment is not a sustainable solution. Officers with less education are significantly more likely to use force to resolve situations. The same is true of officers who are unable to meet physical fitness standards, as they may lack the physical ability to resolve situations in a tactically safe manner. Additionally, officers with subpar fitness levels have a heightened risk of injuries and health problems, leading to increased absenteeism and healthcare costs. Of note, some legislators have introduced bills that would reduce the minimum age for new candidates to 18 years and relax residency requirements, allowing officers to live outside the area they serve. Although these strategies can boost recruitment in the short term, the downsides in terms of officer maturity and community relations must be carefully considered. Moreover, slashing eligibility requirements can undermine public trust in law enforcement, hamper officers’ ability to handle complex situations, and ultimately risk public safety. It is also the opposite of what American citizens actually want. Even though setting the bar lower may increase the number of viable applicants, reducing officer standards should be a last resort, no matter how dire the staffing shortage.

That is not to say all hiring standards make sense. Superficial or cosmetic standards should be adjusted for candidates entering the workforce today. This is perhaps most obvious in the case of tattoo bans that, although less common than previous eras, still exist in some jurisdictions. These rules will have to change sooner or later, as the percentage of Americans with at least one tattoo has risen from 14 percent to 32 percent—a surge in popularity that appears to be accelerating. They are even more common among the 21- to 35-year-old demographic that is most likely to apply to a police academy. Agencies need to stop artificially narrowing the field of potential candidates and instead do everything possible to expand it. In addition to relaxing antiquated tattoo policies, more leniency with regard to credit checks, prior drug use, and minor arrest records could help agencies safely expand the pool of eligible candidates.

Of note, departments that are interested in hiring candidates with higher levels of education will have to start hiring more women, as they outpace men in educational attainment across every major racial and ethnic group. In 1995, men and women were equally likely to graduate from college. Since then, women have outpaced men, with 47 percent of U.S. women ages 25 to 34 earning a bachelor’s degree, compared to only 37 percent of men. Despite being more likely to have reached higher levels of education, women are still underrepresented in policing, occupying only 13.1 percent of law enforcement jobs. Even with outreach efforts like the 30×30 Initiative, this figure is lower than it was in 1999, when women made up 14.3 of the force. This is worth rectifying, as college-educated women are significantly less likely than male peers to use excessive force, racially profile suspects, or be named in a lawsuit. Female officers also tend to be better at de-escalation and can serve as role models for girls who may consider joining the force themselves one day. Targeted online recruitment campaigns emphasizing fitness have been shown to appeal to women, and specialized programs like Denver’s diversity recruitment advisory board are ways to foster an inclusive organizational culture.

Sidebar: Higher Learning, Safer Streets: The evolution of educational requirements in law enforcement reflects a century-long effort to professionalize the field and enhance community trust. Pioneered in 1909 by August Vollmer, Berkeley’s first police chief, the integration of education into policing began with collaborations between law enforcement and academia, culminating in the first criminal justice program at University of California Berkeley in 1916. The 1931 Wickersham Commission Report emphasized the need for higher educational standards to combat corruption and inefficiency. Federal initiatives in the mid-20th century, such as the Law Enforcement Education Program (LEEP) and the Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act of 1968, enabled more than 100,000 officers to earn college credits by the 1970s and expanded criminal justice programs nationwide. By the late 20th century, departments like the NYPD required 60 college credits or equivalent military experience for new recruits, and agencies such as the Federal Bureau of Investigation had mandated bachelor’s degrees for most positions, reflecting a national consensus on the value of higher education in promoting analytical thinking, ethical decision-making, and leadership. Concurrently, research highlighted the importance of inclusive training environments, addressing barriers faced by female trainees and stressing how diverse perspectives bolster intellectual rigor. Together, these developments demonstrate the critical role of higher education in fostering effective, ethical, and community-focused policing.

Keeping the Good Ones

Across the country, officers are leaving the force early, abandoning their pensions to seek new opportunities. Between 2020 and 2023, law enforcement resignation and retirement rates increased by 47 percent and 19 percent, respectively. Even though salary is not the primary consideration for most people when initially choosing a career, it is the single most frequently cited reason for resigning, making pay more important to employee retention than recruitment. Salary typically becomes an issue if: (1) it is not competitive and (2) the employee is unhappy. In general, people who dislike their jobs or who are struggling to pay bills will switch jobs for a 5 percent pay raise, or even less, whereas satisfied employees generally require at least a 20 percent pay increase before they consider resigning. For many, a job they love is worth even more.

Retention > Recruitment

While most large agencies have a division specifically dedicated to recruiting, few have a division specifically dedicated to retention. The discourse on recruitment tends to overshadow retention, but from a first-principles perspective, this focus should be reversed because high turnover is even more concerning than dwindling recruitment. Generally speaking, it is far better to keep good employees than to hire new ones because training a replacement requires major investments of time and money. Estimates vary, but with expenses related to academy tuition, equipment, and on-the-job training, it costs approximately $20,000 to $100,000 to train a single police officer. In the United States, officers spend about 833 hours, or 21 weeks total, in training, which is a substantial investment, especially for smaller departments. These upfront costs are the primary reason that replacing an officer with three years’ experience costs more than twice their annual salary (Table 1).

Table 1: Turnover Costs

| Category | Costs (FTE = full-time employees) |

|---|---|

| Recruitment | Advertising, recruiter FTEs, bonuses |

| Selection | Medical tests, review-board FTEs, investigator FTEs, medical, psychological exam, drug screening |

| New employee | Payroll, information technology, new uniforms and equipment |

| Training | Academy, orientation, trainer FTEs, in-service training |

| Operating | Overtime to cover vacancies, loss of productivity, increased further turnover, peer disruption, disruption of department operations, lower morale, missed deadlines |

| Intangible | Loss of knowledge and experience, disruption or loss of community relationships, lower morale |

Additionally, the most effective agencies realize that retention begins before an officer is even selected. The goal should be to maximize the forces pulling employees into an organization while minimizing the forces pushing them out. While the city of Austin’s decision to offer a $15,000 signing bonus will no doubt bring in fresh cadets, those funds could be even more effectively deployed in the form of retention bonuses. In fact, sustained improvement in turnover can alleviate the need for expensive and time-consuming recruitment campaigns altogether. Some proposals opt for the stick rather than the carrot. For example, proposed legislation in Indiana would allow governments to seek “reasonable reimbursement” from police officers for sunk costs related to training and equipment if they leave to work for “a nonpublic employer” within three years of being hired. The legislation would even allow agencies to seek reimbursement from other “units of government” that lure officers away from police departments after training.

Pension Tension

Compensation is not just about money. As people age, their priorities change, as do the benefits they value. Once considered the gold standard of retirement, public pensions have been drastically scaled back since the 1990s, making them less of a draw than they once were. Still, even less-generous pensions can be a powerful incentive to stay once someone is on the force, especially for veteran officers. Until recently, federal law unfairly penalized law-enforcement retirees by offsetting Social Security, spousal, or survivor benefits based on their government pension income. On Jan. 5, 2025, however, President Joe Biden signed the Social Security Fairness Act, repealing these provisions and ensuring that law enforcement officers receive all the retirement benefits they have earned. In addition, some states are allowing veteran officers to defer retirement, signaling a respect for their experience and years of service and providing an incentive to stay on the job. When Arizona began letting officers defer retirement several years ago, 58 percent of qualified officers took the extension, massively reducing attrition. Wyoming now permits retirees to return to work after a one-month break without losing their pension, enabling them to work part-time while still collecting their retirement benefits—a crucial advantage for rural agencies facing acute workforce challenges. (For more pending state legislation, see Appendix 2.)

Great Expectations

Most officers who quit do so within the first three years of hire. The fact that so many young officers come into the field, experience the job, and leave almost immediately indicates that many departments are not properly managing expectations. When hiring, police agencies too often focus exclusively on the positive or exciting aspects of law enforcement even though the reality is less glamorous than what the public sees on crime dramas like Law and Order. A fully transparent hiring process can help dispel romanticized misconceptions, accurately calibrate expectations, and ensure that officers and their families understand the good and challenging aspects of the job. These conversations are not easy, particularly for departments desperate to attract talent, as they require honest and upfront discussions on sensitive topics that do not come up in normal job interviews. Some departments have found that conveying the realities of policing is not always possible from behind a desk and require applicants to complete a series of ride-alongs before making an employment offer. The International Association of Chiefs of Police’s (IACP’s) “Discover Policing” program is also helpful, as it offers a series of realistic job preview videos that can be used in recruitment to help agencies weed out unserious or unprepared recruits.

Upward Mobility

Like any professional, officers are seeking more than a job—they want a career. Opportunities for career development are strongly correlated with retention throughout the labor market, and police officers are no exception. Workers who fail to achieve their career objectives are more likely to become frustrated and look for a new job. In addition, when officers do not receive sufficient training, they make more mistakes and have higher use-of-force rates, leading to lawsuits, negative press, and poor organizational performance.

The dynamic, evolving nature of policing makes ongoing training key for officer readiness, but it can also serve as an incentive to stay. Specialized career tracks in areas like cybersecurity, forensic analysis, and crisis negotiation can align officers’ professional development with personal competencies and interests. Agencies that fail to provide such development opportunities fundamentally misunderstand what draws people to public service and will continue losing personnel. Last year, an IACP survey found that 65 percent of U.S. agencies reported reducing services or specialized units, prioritizing essential patrol functions only. This is clearly problematic from a service perspective, but it is also counterproductive from a recruitment and retention perspective. Proactively offering employees more responsibility and pathways for advancement communicates their value and can foster creativity. For those with leadership potential, the IACP offers a training program to prepare young officers for supervisory and management roles.

Sidebar: EdCOPS Act of 2024: Pending federal legislation like the EdCOPS Act of 2024 proposes providing public safety officers—and their families—with federal educational assistance. The bill would provide law officers up to 45 months of financial support for education and would even allow the funds to be passed on to their spouse or children. Initiatives like this demonstrate a commitment to professional development and provide the public with more professional policing. (For more federal legislation, see Appendix I.)

Millennial employees are the group most likely to cite limited career prospects as a reason for leaving their current position. This can be a problem in traditional law enforcement hierarchies, where the only way to move up is to assume a management position. Unfortunately, in many smaller agencies, leadership vacancies only become available when someone retires or dies. Additionally, the system leaves little room for officers who may have no interest or capacity for management but are nonetheless an invaluable asset to the department. Many departments are developing alternative opportunities, such as dual-track promotion structures that cater to individuals who want to rise through the ranks, advance their careers, and—crucially—earn more, without becoming supervisors as was once required.

The Feedback Loop

Feedback is the easiest, least expensive way to incentivize exceptional performance. When individuals do not receive recognition for their work, they are less inclined to continue working hard and have no way of knowing whether they are on the right track or not. Even negative feedback, if offered constructively, is valuable for employees who are eager to improve. For feedback to be meaningful, it must be timely, specific, behavioral, and job- related. A hockey coach does not wait until the end of the season to correct a player’s performance; they pull the player to the side, explain the play, and get their head back in the game. By quickly reinforcing good behavior and addressing bad behavior before it becomes a persistent problem, supervisors can help officers operate at peak performance, build their self-confidence, and integrate into the department. Supervisors who fail to provide appropriate feedback allow poor work habits to form, resulting in citizen complaints, human resource problems, or worse.

Wellness Check

Policing can take an emotional and physical toll, leading to injuries and medical retirements. Overworked officers have also been shown to make suboptimal decisions and be susceptible to burnout. Tragically, the suicide rate for police officers is 54 percent higher than that of the civilian population. Although many police agencies have specialized peer volunteers who spring into action after a critical incident, most of what officers do during a typical day, while stressful, falls outside of the scope of critical care. Agencies should not wait for something traumatic to happen to offer their officers helpful resources. Employee wellness programs can help bridge that gap. One example is the Sheriff’s Office in Sedgwick County, Kansas, which provides fitness equipment, gym memberships, and even catered food. And not only does this benefit officers’ health, but limited research also indicates that officers who maintain healthy physical fitness levels are significantly less likely to use lethal force.

Key Recommendations

Addressing the recruitment and retention crisis in law enforcement requires a fundamental shift in how agencies attract, develop, and support their workforce. Agencies must implement forward-thinking strategies to ensure sustainability, professionalism, and effectiveness. The recommendations that follow provide evidence-based, practical solutions to enhance workplace conditions, modernize recruitment, optimize staffing, and foster long-term retention. These approaches have the potential to improve officer satisfaction and agency effectiveness as well as strengthen public trust and community relationships. Agencies that have implemented some of these initiatives are seeing measurable improvements in recruitment numbers, job satisfaction, and overall workforce stability, signaling a positive path forward for policing’s future.

- Enhance Workplace Conditions

- Promote work-life balance, autonomy, and leadership support to boost job satisfaction

- Foster a culture of safety and resilience with wellness programs and peer-support networks

- Implement job-enrichment and -rotation strategies to engage officers and train them in useful skills

- Equip officers with reliable, modern tools and technology to demonstrate a commitment to their safety and effectiveness

- Improve Compensation and Benefits

- Offer competitive salaries that reflect the risks of policing, and implement sliding-scale compensation based on officer priorities

- Provide incentives like signing bonuses, tuition reimbursement, and housing assistance

- Encourage community residency with reduced taxes, lower utility bills, or take-home vehicles

- Optimize Staffing and Workloads

- Conduct a staffing analysis to align workforce size with community needs

- Restructure job roles and schedules to offer more flexible shifts

- Employ civilians for administrative tasks to free officers for critical roles

- Offer interim roles during background checks and academy training

- Modernize Recruitment Practices

- Create interactive websites that tell a story using audio and video

- Streamline hiring with rolling academies and digital processes

- Implement an employee-referral system to involve the entire department in recruitment

- Require ride-alongs for applicants to ensure that they have a realistic understanding of the job before they are hired

- Foster Professional Growth and Retention

- Conduct “stay” interviews to identify and address workplace dynamics and retain high-performing officers

- Offer structured career-development programs, leadership training, and long-term-growth opportunities

- Implement dual-track promotion structures to offer career advancement for non-supervisory roles

- Incentivize continued service with employment bonuses tied to length of service

- Expand Recruitment Pools

- Relax outdated policies on tattoos, past drug use, and minor offenses to align with changing societal norms

- Partner with colleges, especially in criminal justice and STEM departments, to create streamlined pathways into policing

- Appoint recruitment liaisons for targeted outreach, mentorship, and community partnerships

- Leverage Evidence-Based Policing

- Advocate for a “more police, fewer prisons” approach, emphasizing crime deterrence over incarceration

- Highlight the visible deterrent effect of community policing to reduce crime proactively

- Secure Federal and State Support

- Increase Department of Justice grant funding for recruitment and hiring initiatives

- Advocate for sustained state investments in long-term recruitment pipelines

The implementation of these recommendations offers law enforcement agencies a sustainable path forward in addressing staffing shortages and improving workforce morale. Agencies that have embraced some of these strategies are already experiencing higher recruitment rates, lower attrition, and a more engaged and professionally fulfilled police force. By rethinking traditional hiring models, investing in officer development, and fostering a supportive work environment, policing can adapt to modern workforce expectations while maintaining high professional standards. Moving forward, continued evaluation and adaptation of these approaches will be critical to ensuring that law enforcement agencies remain competitive employers capable of attracting and retaining the next generation of skilled and dedicated officers.

Conclusion

Police officers are leaving the force to pursue safer, more lucrative, and less scrutinized careers, taking invaluable expertise and institutional knowledge with them. The IACP has declared the crisis “the most urgent challenge facing law enforcement today,” with far-reaching implications for public safety, community trust, and the sustainability of policing as a profession. In the business world, understaffing might lead to less profit, falling stock prices, or unfinished products. In law enforcement, the consequences are much more serious. From unsolved cases to slower response times, the operational impact goes beyond public safety, reinforcing the perception of a profession in crisis. Ultimately, the future of law enforcement depends on its ability to adapt to evolving societal expectations and labor-market dynamics. Agencies that fail to do so will continue to shrink, while those that succeed will rebuild their ranks with dedicated public servants, laying the foundation for a more sustainable, professional, community-oriented model of policing.