USPS Pensions vs. the World: More Rules, Worse Funding

The United States Postal Service (USPS) holds

a special place among the world’s mail carriers. It moves more mail and generates

more revenue than anyone else, with one of the largest postal workforces on the

planet. But being the biggest isn’t cheap, and the USPS faces more rules than

foreign carriers ever have to deal with. Nowhere is this divide more visible

than in the Service’s attempts to pay for the retirement benefits it promises

to workers.

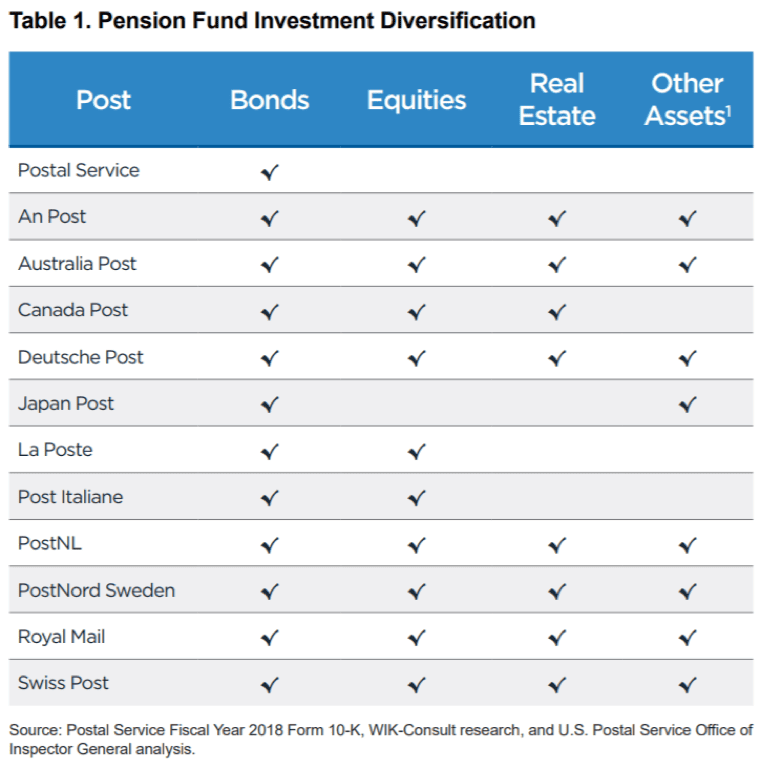

In a new white paper, the USPS inspector

general’s office (OIG) compares America’s governance of postal pension benefits

to peer agencies in other developed economies. The report notes a few key

differences between the USPS and these other postal services, the foremost

being the American agency’s prohibition on diversification of its investment

portfolio. As the table below illustrates, USPS pension funds are invested

solely in bonds, specifically special-purpose, low-risk treasury bonds created

specifically for postal savings. Different rules apply to investment of pension

savings for other federal workers. But limited risk and no diversification also

means limited potential return when the economy grows.

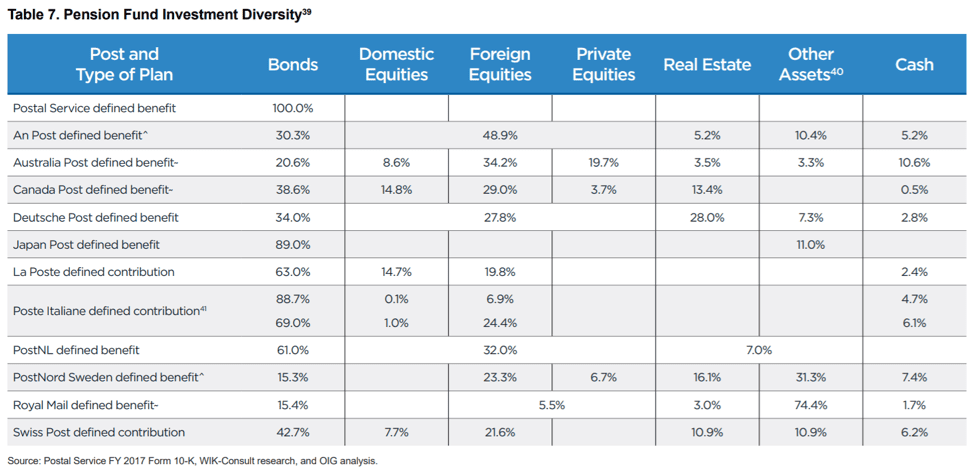

As we can see, the USPS is unique in its

apprehensive investment strategy. The OIG explains that, “Unlike the Postal

Service, the 11 foreign posts generally base the financing of their pension

plans on sophisticated portfolio and risk optimization, attempting to capture

opportunities in capital markets at home and abroad.” That said, bonds still

form the preponderance of most postal pension investment portfolios, with the

balance spread across investment types. Low-risk assets make a lot of sense for

self-funding mail companies, limiting pressure for taxpayer bailouts when

global economic downturns damage government balance sheets.

The problems with extra-conservative

investment rules arise when postal finances are weak and pension plans go

underfunded. Conversely, taking on extra investment risk during economic

expansions can help mail agencies close funding gaps left by failures to save

enough to pay future retirees.

This problem is particularly acute for the USPS,

whose pension plan funding levels are worse than peer agencies. Despite having

more than $278 billion in assets, USPS pensions are underfunded by more than

$40 billion. Only Japan Post comes anywhere close to this level of underfunding,

holding a shade under $20 billion in liabilities to its retirees.

In a previous report from 2017, the OIG

noted that easing the mandates that force USPS pensions to be invested in

special-purpose treasuries could almost completely close the pension funding

gap with greater returns on what the agency has already saved.

The

new study showcases other countries’ postal

pension savings investment models, providing a multitude of options should

Congress make changes to shore up the agency’s shaky finances. In Table 4 (not

shown), it lists the fiduciary rules that apply to pension investments in each

country studied, all of which allow investment options legally unavailable to

the USPS.

Notably, no other major country studied has

special laws to restrict the scope of postal pension investments. Rather, they

have blanket rules for pensions that apply to “other employees and pension

funds in their respective countries.” Many mandate that pension funds hold a

diverse portfolio of assets, the exact opposite of the rules that bind the USPS.

Countries like Canada and Australia have been

leaders in pension fund diversification for decades, with broad discretion to

invest in assets that will yield appropriate returns. Funds in both nations

have been rewarded with returns on assets in an array of countries and industries. Other countries place

some guardrails on pension fund investment, like Italy’s rules that bar

investment in real estate or Ireland’s rules that require more than half of

investments to be in “regulated markets.”

The facts of the OIG report paint a picture of

an agency held back by special rules that treat its workers differently from

other federal employees to the detriment of both the USPS and its workforce.

Moving to a broader system that reconciles the differences between how the USPS

invests pension savings and how the government at large invests savings for

other federal workers would benefit every substantial postal constituency. $278

billion in investments could buy plenty of diversity to insulate the USPS from

economic downturns, if Congress ever lets it buy something other than bonds.