Prenatal Substance Use Laws Inadvertently Endanger Healthy Families: A Review of Laws Affecting Pregnant Women in Recovery and Their Children

Authors

Download our infographic and explainer on “How Prenatal Substance Use Laws Inadvertently Endanger Healthy Families.”

Table of Contents

- Executive Summary

- Introduction

- The Impact of OUD, MOUDs, and Punitive Prenatal Substance Use Laws on Public Health

- Laws Addressing MOUDs During Pregnancy

- Policy Lessons and Takeaways

- Conclusion

Media Contact

For general and media inquiries and to book our experts, please contact: pr@rstreet.org

Specific public policy reforms can help ensure individuals are not punished for taking MOUDs while pregnant.

Executive Summary

Parental substance use is one of the primary reasons children enter the foster care system. Over the last two decades, as the opioid crisis took root and more parents found themselves struggling with opioid use disorder (OUD), the number of children placed in foster care as a result of parental drug use nearly doubled. At the same time, the number of state and federal laws attempting to both address treatment-related issues and punish substance use also increased. Some of these laws have created more problems than they have solved.

Specifically, although research has shown that medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) are an effective and safe way for individuals with OUD to receive treatment while pregnant, state and federal laws often lack clarity on whether MOUD use during pregnancy is exempt from child maltreatment or substance use laws. This can lead to the reporting, investigation, and punishment of pregnant people taking evidence-based MOUDs as prescribed.

To better understand the scope of this issue, we conducted a 50-state analysis of child welfare laws and their inclusion/exclusion of MOUD use during pregnancy. As a result of this research, we have identified specific public policy reforms that can help ensure individuals are not punished for taking MOUDs while pregnant.

Introduction

Across the United States, laws that penalize substance use during pregnancy put expectant mothers who are in treatment for opioid use disorder (OUD) and their families at risk. These laws can lead to criminal charges or trigger child welfare agencies to investigate and separate families, even when the substance used during pregnancy is a prescribed medication. This threat of losing a newly born child leads some women to quit taking their evidence-based, lifesaving medication during pregnancy, even though it is safe for and prevents harms to the fetus.[1] Because of data collection limits and confidentiality laws, it is impossible to know exactly how many women face this dilemma, but studies suggest that thousands of children are removed from families under these circumstances each year.[2] For example, a 2024 investigation of eight states and Washington, D.C. found that nearly 3,700 women had been reported to child protective services (CPS) since 2016 for taking a prescribed medication for OUD (MOUD) while pregnant.[3] Similarly, between 2017 and 2020, healthcare providers in Kentucky reported almost 700 pregnant women to state agencies for taking MOUDs.[4] And between 2022 and 2023, at least 133 women nationally were criminally charged for substance use during pregnancy, 16 of whom were taking MOUDs.[5]

Even women who face only civil (as opposed to criminal) consequences resulting from their substance use during pregnancy may be subject to investigations and lengthy monitoring periods and risk losing custody of their children. But these life disruptions—especially family separation in the absence of imminent risk to the child—do not benefit the involved parties; in fact, in many cases, they increase harms for both parents and children.[6] In addition, some women with OUD choose to not seek prenatal care or utilize healthcare services during and after a pregnancy for fear that their children will be taken from them.[7] This fear can even lead those who are prescribed and taking MOUD to make the dangerous choice of stopping the medication altogether.[8] Not only do these choices present health risks to the mother and fetus, but they also make it more difficult to keep families together and keep parents engaged in active, evidence-based recovery programs, both of which improve outcomes for all.[9]

Government can support the best interests of families and children by ensuring that patients with OUD are not criminalized or at increased risk of investigation simply for taking MOUDs as prescribed during pregnancy. To shape policy toward this end, it is first important to understand the legislative landscape related to prenatal substance use and, specifically, the use of MOUDs during pregnancy. Therefore, in this study, we:

- Review the existing evidence on OUD during pregnancy and the known public health effects of laws targeting prenatal substance use;

- Assess the current legal landscape impacting individuals taking MOUDs during pregnancy;

- Highlight relevant policy challenges and possible solutions for lawmakers to consider.

The Impact of OUD, MOUDs, and Punitive Prenatal Substance Use Laws on Public Health

Evaluating and improving the legislative landscape around prenatal substance use—and especially prenatal MOUD use—requires understanding and balancing a complex web of risks and benefits for both the pregnant patient with OUD and their child.

OUD and Pregnancy

An estimated 2.5 million to 7.6 million Americans are living with OUD, many of them of child-bearing age.[10] In fact, roughly 0.4 percent of pregnant women use illicit opioids, and 1.4 percent report using prescription opioids in ways other than how they were prescribed.[11] Untreated OUD during pregnancy can lead to a range of significant risks for both the expectant parent and their child.[12] Roughly 16 percent of pregnancy-associated deaths between 2017 and 2020 were the result of a drug overdose—a tragedy that has been on the rise in recent years.[13] In addition, untreated OUD is associated with a lack of prenatal care as well as an increased risk of stillbirth, preterm labor, neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome, and other complications.[14]

Fortunately, available medications can dramatically reduce the risk of death or other opioid-related harms for pregnant women and their children.[15] Collectively referred to as medications for opioid use disorder, or MOUDs, methadone and buprenorphine are considered to be gold-standard treatments for OUD.[16] They curb cravings and withdrawal symptoms, dramatically reducing the use of illicit drugs and improving treatment retention.[17] They also decrease overdose risk by up to 80 percent compared to non-medication treatments.[18] These benefits extend both to individuals who take MOUDs during pregnancy and to newborns who were exposed to substances in utero.[19] Specifically, taking MOUDs during pregnancy is associated with reductions in overdose, preterm birth, and low birth weight.[20] Furthermore, although taking MOUDs during pregnancy can result in neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) in some newborns, the condition is predictable and treatable and does not deter medical experts from recommending MOUDs for pregnant individuals with OUD.[21]

The benefits of treating OUD medically during pregnancy even extend after the birth. Research has found that women who take MOUDs during pregnancy are more likely to continue with treatment after their child is born.[22] In addition, their infants attend more well-child visits and have a lower risk of hospital readmission.[23] MOUDs also improve family outcomes, increasing parental stability and thus the likelihood that families will stay together.[24] In fact, because of their limited risks to both the mother and the fetus, MOUDs are considered preferable to abstinence—even when facilitated by naltrexone or medically managed withdrawal.[25]

Despite these clinical benefits and recommendations, taking MOUDs during pregnancy is in and of itself a risk factor for punitive legal action that can lead to burdensome surveillance, criminalization, and custody loss, potentially making the decision to take this medication complicated and distressing.[26]

The Public Health Effects of Punitive Prenatal Drug Laws

One way that lawmakers have tried to reduce the potential harms of substance use during pregnancy is through legislation. However, these laws—which typically either require the reporting of suspected or confirmed prenatal substance use to state child welfare agencies or include substance use in their definition of child abuse or neglect—can often negatively affect the well-being of families as a whole as well as the individual parents and children within those families.

Between 2008 and 2017, almost one-third of the 2.5 million children entering foster care were there primarily or exclusively because of parental substance use, including in-utero exposure.[27] In particular, substance use during pregnancy is a leading cause of custody loss and a major driver of children entering the foster care system.[28] It is therefore no surprise that from 2000 to 2017, as opioid use skyrocketed and fentanyl proliferated across the United States, driving increases in OUD, overdose risk, and punitive prenatal drug use policies, the number of children in foster care because of parental drug use nearly doubled.[29] Although state and federal governments were attempting to reduce the number of “substance-exposed” newborns by enacting prenatal drug use legislation, they created a system that increases risks to the very children they were aiming to protect, as well as to mothers in recovery.

While information on the public health impact of policies related to prenatal MOUD use is lacking, research on the effects of enforcing laws prohibiting substance use during pregnancy is growing and can be leveraged to inform best practices related to MOUD use during pregnancy.

Perhaps most importantly, research indicates that laws targeting parental substance use during pregnancy do not benefit parents or newborns (Table 1).[30] In fact, punitive policies have been associated with an increased risk of NAS, decreased linkage to prenatal care, and, notably, reductions not in prenatal substance use but in pregnant women’s engagement in substance use disorder treatment.[31] Studies have also found that punitive prenatal substance use laws are associated with increases in poor birth outcomes, including lower birth weights, younger gestational ages, lower average Apgar scores, and increased rates of stillbirth and infant mortality.[32] Furthermore, mothers who lose their newborns because of drug use have an increased risk of experiencing overdose, as well as having poorer mental health and lower levels of treatment motivation.[33]

Table 1: Harms Associated with Policies Penalizing Prenatal Drug Use

| To Fetus/Infant | To Mother |

|---|---|

| Lower birth weight | Increased risk of overdose |

| Younger gestational age | Higher risk of mental health issues |

| Lower Apgar scores | Lower rates of OUD treatment engagement and motivation |

| Increased risk of stillbirth | Suboptimal prenatal care |

| Increased risk of mortality | |

| Greater risk of NAS | |

| Suboptimal prenatal care |

Given these findings, it is unsurprising that several high-profile cases have underscored that women who take MOUDs during pregnancy risk considerable harms to themselves and their families—not because of the medications, but because of policy repercussions.[34] Specifically, when expectant mothers who are taking MOUDs become involved with CPS, the fear or trauma of losing their infants and the disruption caused by lengthy surveillance periods can derail recovery efforts.[35] Moreover, the stress, stigma, and disruption caused by this surveillance, combined with agencies’ often unrealistic expectations and arbitrary requirements and recovery timelines, can lead to permanent family separation and an increased risk of OUD relapse and overdose.[36] In addition, qualitative research suggests that expectant mothers’ fear of these consequences can force them to choose between their medication-based recovery and the risk of losing their child.[37]

Laws Addressing MOUDs During Pregnancy

Given that mandated reporting and punitive prenatal substance use laws cause such significant harms to parents, children, and the family unit, it is important to better understand the current legislative landscape. In this section, we summarize federal and state laws related to prenatal substance use and assess whether state laws include specific language to exempt and protect women who are taking MOUDs during pregnancy.

The Federal Mandate

The Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act (CAPTA) was enacted in 1974 and has since been amended and reauthorized several times, most recently in 2019.[38] CAPTA “provides Federal funding and guidance to States in support of prevention, assessment, investigation, prosecution, and treatment activities,” and more.[39] In accordance with this mandate, states that receive funding must have policies in place requiring healthcare providers to notify the relevant agency of any newborn that shows signs of being “affected by substance abuse.”[40] Although a “notification” is distinct from a “report” to CPS in that information may be deidentified and does not necessarily lead to an investigation, CAPTA allows states to use the more punitive “report”—even in cases involving only MOUDs.[41] In fact, many states have protocols in place mandating that any notification to CPS of a substance-exposed infant triggers an investigation.[42] Importantly, “substance-affected infant” is not clearly defined in CAPTA, so some states may penalize women for exposing a fetus to substances, even if the exposure does not cause harm.[43] Furthermore, simple substance exposure can even end up penalizing women who have received controlled medications such as painkillers during the birthing process.[44]

The Keeping Children and Families Safe Act of 2003 added the Plan of Safe Care (POSC) to requirements for states to receive CAPTA funding.[45] POSCs are intended to be developed between the patient and their provider and include “appropriate referrals to CPS and other relevant systems” to address the needs of substance-affected newborns.[46] Although POSCs do not require reporting under this federal guidance and are explicitly not to be construed as an indication of child maltreatment, they can still prompt screening and investigation.[47]

When CAPTA was originally enacted, it pertained only to illicit drugs. However, in 2016, the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act (CARA) changed CAPTA in several ways, the most relevant of which was striking the word “illegal” in relation to substance-exposure notifications and POSCs.[48] This modification makes it more likely that states will notify CPS of any prenatal substance use—including prescription medications and alcohol—but does not account for the fact that it could unintentionally capture parents who are taking medications as prescribed.[49]

Because CAPTA is relatively broad, it serves more as a general guideline for states, which differ in their respective approaches to the issue of prenatal substance use. In fact, research has found that no state completely complies with all of CAPTA’s guidelines, and several states have no legislation at all in place to address substance-affected infants or support their families to optimize social and health outcomes.[50]

Analysis of State-Based Legislation of MOUD Use During Pregnancy

In our review of current state-based legislation, we aimed to capture and clarify states’ legislative treatment of MOUD use during pregnancy by conducting a legal scan (a systematic review of an existing policy across multiple jurisdictions at one point in time) and qualitative analysis.[51]

Methodology. We conducted the legal scan in several iterative stages. First, we reviewed existing assessments—including peer-reviewed studies and federal summary documents—of the laws pertaining to substance use during pregnancy. We used findings from those resources to identify a baseline of legislation to scan as well as to develop questions for our own analysis. We ultimately established two key baseline questions:

- Does the state require notification of substance-affected infants? (This question uses the thresholds of “notification” and “substance-affected,” as these are necessarily inclusive of both “reporting” and “substance exposed.”)

- Does the state define parental/prenatal substance use alone as a form of child maltreatment (including abuse, neglect, or endangerment)?

We selected relevant laws to scan by identifying laws from previous studies, searching the Child Welfare Information Gateway to discover laws related to prenatal and parental substance use and “substance-exposed” or “substance-affected” infants, and identifying bills related to prenatal substance use that had been newly enacted since 2019 (the cutoff date of the older of the two previous assessments we used). After this process, we cross-referenced the identified laws and bills to create a master list of laws to be coded.

We then downloaded the identified laws and bills directly from state websites when possible and, if necessary, from legal databases (i.e., Justia Law, Thomson Reuters Westlaw, and LegiScan). The legislative text of the laws and bills was then coded according to the above questions to create an up-to-date assessment of general laws related to prenatal substance use. Specifically, we coded the text for protections related to prenatal MOUD use applying the following question: Does the state exclude prescribed substances—including or exclusively MOUD—from their laws penalizing prenatal substance use?

Throughout this iterative process, we triangulated our assessment with prior legislative scans. In the case of discrepancies, we checked for updates to the laws, discussed disparate interpretations between scholars on our research team, and consulted state-issued guidance documents. Importantly, although the findings presented below represent our interpretation of state-by-state policies for the purposes of understanding the laws’ potential population-level impacts, they should not be taken as legal guidance.

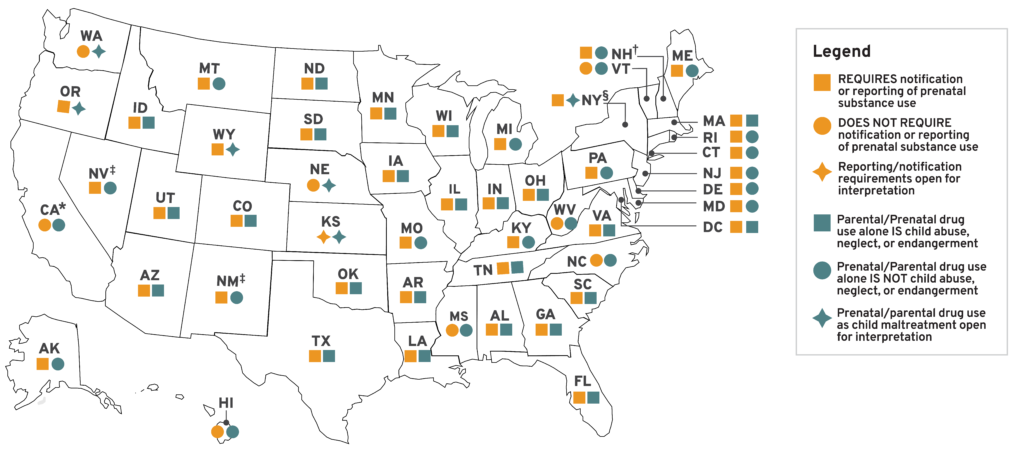

Analysis of Laws in the 50 States and Washington, D.C. Our legal scan of prenatal substance use reporting and child abuse, neglect, and endangerment laws was largely consistent with prior analyses of these legislative environments, finding that the vast majority of U.S. states have some sort of punitive structure in place for women who use substances during pregnancy.[52]

We separated prenatal substance use policies into two categories. Those that:

- Require notifications or reports to child welfare agencies if an infant is born either “substance exposed” or “substance affected.” We define substance exposure as a lower bar that does not explicitly indicate harm to the child—and may be revealed by the mother or through toxicology screening of the mother or infant—whereas a substance-affected infant would show physical, psychological, or emotional symptoms of that exposure.[53]

- Include prenatal substance use alone in definitions of child maltreatment. We use the term child maltreatment broadly to cover neglect, abuse, and endangerment laws.

As of our February 2025 analysis, all but six states—California, Hawaii, Mississippi, North Carolina, Vermont, and West Virginia—have some type of punitive or surveillance-oriented policy in place to address substance use during pregnancy. It is noteworthy that California does require counties to establish local protocols for addressing prenatal substance use, but the state does not require reporting or notification to CPS.

In a number of states, the only relevant prenatal substance use laws we identified contained vague language that leaves specific actions open to interpretation. For example, although neither Kansas nor Nebraska explicitly addresses prenatal substance use in their child maltreatment laws, they do criminalize general behaviors such as “failing to provide adequate nurturance,” which some may interpret as including substance use.[54]

In other states—including New Hampshire, New Mexico, and Nevada—laws do not consider prenatal substance use to be a form of child maltreatment, but they do require providers to develop a POSC and notify state agencies, despite not specifying whether such notifications will result in monitoring or investigation by the agency.[55] Figure 1 provides a visual overview of these laws in each state and Washington, D.C.

Figure 1: States’ Prenatal Substance Use Reporting Requirements and Child Abuse, Neglect, and Endangerment Laws

† POSC must be developed and the state notified of that, but, per law, reporting is required only in cases that involve abuse or neglect.

‡ POSC must be developed and CPS notified of that, but, per law, this notification does not appear to come with monitoring/surveillance.

§ POSC, but it is unclear whether it requires reporting.

Source: Data derived from R Street research.

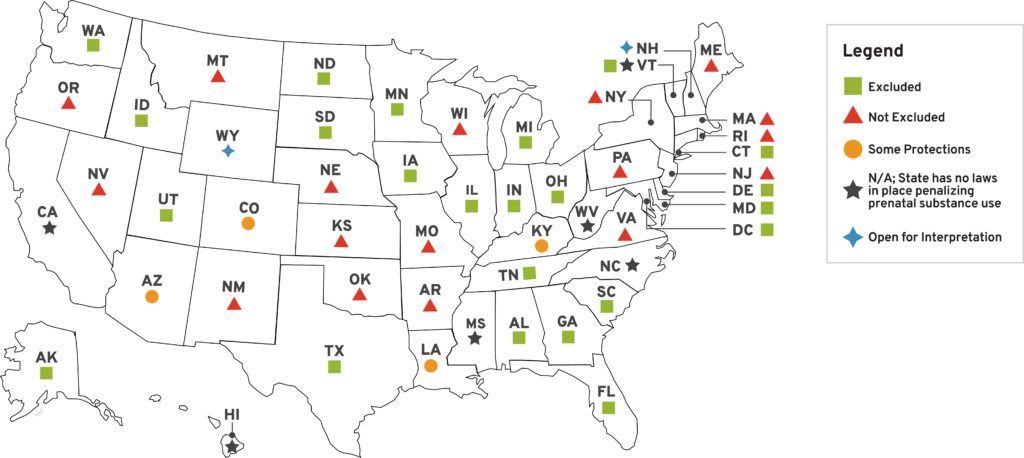

In the six states that lack any punitive policies regarding substance-exposed or -affected neonates, individuals taking MOUDs during pregnancy should not be at risk of being caught up in the child welfare system for taking their prescribed medications as directed. Of these six states, one (Vermont) has specific language protecting prescription substance use during pregnancy. Among the jurisdictions that do have laws penalizing substance use during pregnancy, 21 states and Washington, D.C. have explicit language that protects or excludes women from these laws if the substance taken during pregnancy was a medication taken as prescribed. Together, this constitutes 27 states and Washington, D.C. in which women should not have to worry about facing criminalization or risking custody loss for taking a recommended medication as prescribed during pregnancy.

That leaves 23 states in which the law allows for family separation, or even criminal punishment, if an individual takes MOUD while pregnant. Four of these states—Arizona, Colorado, Kentucky, and Louisiana—offer only limited protections (e.g., excluding prenatal MOUD exposure from neglect definitions, but not excluding it from mandates to report to CPS), and two—Wyoming and New Hampshire—have prescription substance use protections that are open to interpretation. In both states, the law requires that POSCs “take into account” whether the prenatal substance used was a prescribed medication, but neither specifies how this consideration will affect actions taken.[56]

Regardless of whether the language is open to interpretation or only partially protective, this type of legislation leaves families vulnerable to negative consequences. Even worse, the remaining 17 states provide absolutely no protections or exclusions for taking prescription medications during pregnancy.

In these instances, the risk of criminalization and family separation depends on the specific nature of the individual state’s reporting and maltreatment laws (Figure 2).

Figure 2: State-Based Status of Whether Prescribed Substances Are Excluded from Prenatal Substance Use Reporting/Punishment

Thus, to summarize, our legal scan revealed that in 23 states, women who are taking MOUD to manage a life-threatening substance use disorder during pregnancy are risking being targeted by child welfare agencies or subjected to criminal charges. Meanwhile, in 27 states and Washington, D.C., women should not be at any risk of criminalization or losing their child for taking MOUD as prescribed during pregnancy. However, even in these 28 jurisdictions where prenatal MOUD use should not put women or their families at risk, legislative vagueness—as well as hospital policy, provider bias, and provider understanding of the law—can increase a patient’s chance of facing punitive consequences.[57]

These issues are exacerbated by the fact that some states’ laws require providers to go beyond simply assessing whether the medication was prescribed to the patient; they also require that providers determine whether the patient was taking the medication as prescribed. For example, Tennessee’s law states that a “drug exposed child (severe)” includes “[i]nfants born with a diagnosis of Neo-Natal Abstinence Syndrome (NAS) where the diagnosis is not based on the mother’s prescribed and appropriately followed Medication-Assisted Treatment.”[58] Similarly, in Indiana, exclusions based on a pregnant person’s use of prescription medication require that they were taking the medication in “good faith.”[59] While such language may seem to be a common-sense addition, the majority of medical practitioners do not receive extensive training in substance use disorder, and, as such, may be poorly equipped to make such nuanced assessments.[60]

Policy Lessons and Takeaways

With an improved understanding of how policy treats prenatal exposure to MOUD—particularly as it relates to child maltreatment and mandatory reporting—we can offer public policy recommendations that support both family well-being and evidence-based OUD recovery. Because federal law, via CAPTA and CARA, stipulates much of what states do regarding substance use during pregnancy, reforms are needed at both the state and federal levels. Overall, policy reforms pertaining to MOUD use during pregnancy fall into three categories: the unintended consequences of federal law, the vagueness of state law, and an overreliance on punitive measures across the board.

1. Clarify definitions in federal law to avoid unintended consequences.

Together, CAPTA and CARA provide the framework that states use to navigate OUD, MOUD, and POSCs during pregnancy. Yet their lack of clear guidance on MOUD use during pregnancy puts this recovery pathway on shaky ground. This leads to unintended downstream consequences. For example, CAPTA does not effectively delineate between notifying and reporting conditions or mandate that a POSC is not, in and of itself, grounds for investigation. This allows states to use reporting (rather than notification) in cases of MOUD use during pregnancy and can lead to family separation and/or deferred OUD treatment.[61] In addition, although CAPTA requires notification for “substance-affected” infants, it offers no clinical definition of the term, leaving states to interpret it as they see fit.[62] Many states therefore use a threshold of “exposure,” which may be confirmed by the presence of a controlled substance or metabolites in the infant’s or mother’s bloodstream, regardless of whether there are signs or symptoms that the child has been affected. This is problematic not only because it so widely expands the net of what constitutes harm, but also because the tests used to confirm exposure have been shown repeatedly to be faulty (e.g., picking up a mother’s ingestion of poppy seeds as opioids).[63]

Furthermore, CARA’s expansion of notification and POSC requirements to include legal as well as illegal drugs implicates that prescription medications like MOUD are problematic. While this act included legal drugs in the definition to better address the rise of the non-medical use of prescription opioids, as well as to better monitor babies born with fetal alcohol syndrome, this means that taking MOUD during pregnancy can lead to punitive measures.[64] In practice, as this study demonstrates, states may criminalize or require the reporting of medication use during pregnancy, even when the medication is taken legally and as prescribed. This, in turn, can contribute to the risk of unnecessarily separating families in which a parent is using MOUD as a recovery tool. Federal law could help reduce these risks for families by explicitly excluding MOUD and other prescribed medications from its own guidelines and definitions related to the reporting of substance-affected infants.

2. Eliminate vagueness on prenatal substance use in state law.

Leaving state laws vague on what forms of prenatal substance use constitute child maltreatment leads to misinterpretation, potential punishment for those taking MOUD, and fear among mandated reporters that can lead to overreporting.[65] Making state laws more explicit around MOUD and prenatal substance use could primarily be done through specific carve-outs, or protections, of parental/prenatal MOUD use from child maltreatment laws and laws pertaining to the reporting of substance-exposed or -affected infants. Only about one-half of all states currently make clear that the use of MOUDs is not grounds for reporting and/or punishment. Vague language ultimately leaves such judgment calls up to the discretion of healthcare providers (who may feel pressure to overreport to minimize the risk of steep penalties in the rare but tragic cases where actual child maltreatment goes unreported) and state governmental agencies tasked with upholding the law.[66] Strengthening state language on prenatal substance use, including MOUD, could lessen the tendency to overreport and unnecessarily investigate or separate families as a result.

3. Reduce the threat of punitive measures in healthcare settings.

Although mandatory reporting is designed to protect children from maltreatment, the threat of punitive measures for parents who use MOUD can lead to poorer health and social outcomes for parents and children alike.[67] From a clinical perspective, MOUDs have been shown to be safe and effective, even during pregnancy, and increase the likelihood that more parents and newborns will be healthy and stable, enabling families to stay together postpartum and beyond.[68] Unfortunately, MOUDs are tangled up in substance use and child maltreatment laws, and the punitive nature of these laws undermines the degree to which MOUDs can help keep families together. Furthermore, because MOUDs are associated with better recovery and healthcare outcomes, the threat of punishment for taking MOUDs during pregnancy—which leads to fewer touchpoints with the healthcare system—can actively harm children and parents alike.[69] For states with unclear language on what constitutes child maltreatment and substance use, policymakers should consider adding language that protects parents who are taking medications as prescribed to ensure that family separation is a last resort. This is critical, as family separation comes with a number of harmful consequences of its own, especially when there is no evidence of current or imminent harm to the child.[70]

Conclusion

Parental and prenatal substance use are among the most common reasons for family separation and foster care entry in the United States.[71] Policies that criminalize expectant mothers who use substances or that mandate reporting to and surveillance by child welfare services often create more harm than safeguards. They can also negatively affect families in which a parent is in active recovery and taking a MOUD. For those taking a MOUD during pregnancy, this reality can have the additional unintended consequence of discouraging prenatal care and OUD treatment engagement and motivation.[72]

To improve outcomes for mothers in recovery from OUD and their children, policymakers must ensure that laws do not penalize women for taking MOUDs during pregnancy. Unfortunately, our analysis of current laws found that federal law and a majority of state laws do not offer sufficiently clear or explicit protections that would allow women to take MOUDs during pregnancy without fear of repercussions. Our analysis also found that, even in states that do offer protections to patients who are taking prescribed medications, the way a law or bill is written can require interpretation by providers. Taken together, these findings suggest that there is ample room for legislative change on this issue in much of the country and at multiple legislative levels.

Policymakers have an opportunity to be part of the solution when it comes to protecting and improving the health and well-being of families. By crafting legislation that is explicit and specific in providing protections for women who are using MOUD during pregnancy, lawmakers can help reduce the likelihood that recovery trajectories will be disrupted, improve the health outcomes for children in-utero whose mothers are in treatment for OUD, and prevent the removal of children from loving homes.

[1]. Shoshana Walter, “They Followed Doctors’ Orders. Then Their Children Were Taken Away,” The New York Times Magazine, July 1, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/06/29/magazine/pregnant-women-medication-suboxonbabies.html; “Opioid Use and Pregnancy,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Feb. 11, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/overdose-prevention/hcp/clinical-care/opioid-use-and-pregnancy.html.

[2]. Ibid.; Wendy A. Bach and Madalyn K. Wasilczuk, “Pregnancy as a Crime: A Preliminary Report on the First Year After Dobbs,” Pregnancy Justice, September 2024. https://www.pregnancyjusticeus.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Pregnancy-as-a-Crime.pdf.

[3]. Walter. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/06/29/magazine/pregnant-women-medication-suboxonbabies.html.

[4]. Ibid.

[5]. Bach and Wasilczuk. https://www.pregnancyjusticeus.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Pregnancy-as-a-Crime.pdf.

[6]. Walter, “They Followed Doctors’ Orders. Then Their Children Were Taken Away.” https://www.nytimes.com/2023/06/29/magazine/pregnant-women-medication-suboxonbabies.html; Shoshana Walter, “Hospitals Gave Women Medications During Childbirth—Then Reported Them for Using Illicit Drugs,” Reveal, Dec. 11, 2024. https://revealnews.org/article/hospitals-gave-women-medications-during-childbirth-then-reported-them-for-using-illicit-drugs; Emilie Bruzelius et al., “Punitive legal responses to prenatal drug use in the United States: A survey of state policies and systematic review of their public health impacts,” International Journal of Drug Policy 126 (April 2024). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0955395924000653?via=ihub.

[7]. Erin C. Work et al., “Prescribed and Penalized: The Detrimental Impact of Mandated Reporting for Prenatal Utilization of Medication for Opioid Use Disorder,” Maternal and Child Health Journal 27:Suppl 1 (December 2023), pp. 104-112. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37253899.

[8]. Ibid.

[9]. Ibid.

[10]. “Only 1 in 5 U.S. adults with opioid use disorder received medications to treat it in 2021,” National Institute on Drug Abuse, Aug. 7, 2023. https://nida.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/2023/08/only-1-in-5-us-adults-with-opioid-use-disorder-received-medications-to-treat-it-in-2021; Noa Krawczyk et al., “Has the treatment gap for opioid use disorder narrowed in the U.S.?: A yearly assessment from 2010 to 2019,” International Journal of Drug Policy 110 (December 2022). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0955395922002031.

[11]. “2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Women,” Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, July 2022. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/slides-2020-nsduh/2020NSDUHWomenSlides072522.pdf; Laura Curran and Jennifer Manuel, “The receipt of medications for opioid use disorder among pregnant individuals in the USA: a multilevel analysis,” Drugs, Habits and Social Policy 25:1 (April 30, 2024). https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/dhs-08-2023-0030/full/html.

[12]. Kristin Harter, “Opioid use disorder in pregnancy,” Mental Health Clinician 9:6 (November 2019), pp. 359-372. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6881108.

[13]. Emilie Bruzelius and Silvia S. Martins, “US Trends in Drug Overdose Mortality Among Pregnant and Postpartum Persons, 2017-2020,” JAMA 328:21 (2022), pp. 2159-2161. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2799164; “Overdose deaths increased in pregnant and postpartum women from early 2018 to late 2021,” National Institutes of Health, Nov. 22, 2023. https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/overdose-deaths-increased-pregnant-postpartum-women-early-2018-late-2021.

[14]. Tatyana Roberts et al., “Opioid Use Disorder and Treatment Among Pregnant and Postpartum Medicaid Enrollees,” Kaiser Family Foundation, Sept. 19, 2023. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/opioid-use-disorder-and-treatment-among-pregnant-and-postpartum-medicaid-enrollees; “Opioid Use and Opioid Use Disorder in Pregnancy,” The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, August 2017. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2017/08/opioid-use-and-opioid-use-disorder-in-pregnancy; “Neonatal Opioid Withdrawal Syndrome (formerly known as Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome),” Cleveland Clinic, June 12, 2022. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/23226-neonatal-abstinence-syndrome.

[15]. “Opioid Use and Opioid Use Disorder in Pregnancy.” https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2017/08/opioid-use-and-opioid-use-disorder-in-pregnancy.

[16]. Linda M. Richmond, “Surgeon General’s Report on Opioids Emphasizes ‘Gold Standard’ Treatment,” Psychiatric News 53:20 (Oct. 12, 2018). https://psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.pn.2018.10b12.

[17]. National Institute on Drug Abuse, “Medications to Treat Opioid Use Disorder Research Report,” National Institutes of Health, December 2021. https://www.freestatesocialwork.com/articles/medications-to-treat-opioid-use-disorder-research-report.pdf.

[18]. Jessica Shortall, “What the…? Safer From Harm on Methadone,” Safer From Harm, March 7, 2024. https://www.saferfromharm.org/blog/what-the-safer-from-harm-on-methadone; Sarah E. Wakeman et al., “Comparative Effectiveness of Different Treatment Pathways for Opioid Use Disorder,” JAMA Network Open 3:2 (Feb. 5, 2020). https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2760032.

[19]. Elizabeth E. Krans et al., “Outcomes associated with the use of medications for opioid use disorder during pregnancy,” Addiction 116:12 (December 2021), pp. 3504-3514. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/add.15582.

[20]. Ibid.

[21]. “Opioid Use and Opioid Use Disorder in Pregnancy.” https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2017/08/opioid-use-and-opioid-use-disorder-in-pregnancy.

[22]. Mir M. Ali et al., “Medications for Opioid Use Disorder During the Prenatal Period and Infant Outcomes,” JAMA Pediatrics 177:11 (Aug. 28, 2023), pp. 1228-1230. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapediatrics/fullarticle/2808881; Krans et al. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/add.15582.

[23]. Krans et al. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/add.15582.

[24]. Martin T. Hall et al., “Medication-Assisted Treatment Improves Child Permanency Outcomes for Opioid-Using Families in the Child Welfare System,” Journal of Substance Use & Addiction Treatment 71 (December 2016), pp. 63-67. https://www.jsatjournal.com/article/S0740-5472(16)30153-2/fulltext.

[25]. “Opioid Use and Opioid Use Disorder in Pregnancy.” https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2017/08/opioid-use-and-opioid-use-disorder-in-pregnancy.

[26]. Walter, “They Followed Doctors’ Orders. Then Their Children Were Taken Away.” https://www.nytimes.com/2023/06/29/magazine/pregnant-women-medication-suboxonbabies.html; Walter, “Hospitals Gave Women Medications During Childbirth—Then Reported Them for Using Illicit Drugs.” https://revealnews.org/article/hospitals-gave-women-medications-during-childbirth-then-reported-them-for-using-illicit-drugs.

[27]. Ibid.

[28]. Danielle N. Atkins and Christine Piette Durrance, “The impact of state-level prenatal substance use policies on infant foster care entry in the United States,” Children and Youth Services Review 130 (November 2021). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S019074092100270X?via=ihub.

[29]. Angélica Meinhofer et al., “Prenatal drug use and racial and ethnic disproportionality in the U.S. foster care system,” Children and Youth Services Review 118 (November 2020). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0190740920308318.

[30]. Emilie Bruzelius et al., “Punitive legal responses to prenatal drug use in the United States: A survey of state policies and systematic review of their public health impacts,” International Journal of Drug Policy 126 (April 2024). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0955395924000653?via=ihub.

[31]. Laura J. Faherty et al., “Association of Punitive and Reporting State Policies Related to Substance Use in Pregnancy With Rates of Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome,” JAMA Network Open 2:11 (Nov. 13, 2019). https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2755304; Cara Angelotta et al., “A Moral or Medical Problem? The Relationship between Legal Penalties and Treatment Practices for Opioid Use Disorders in Pregnant Women,” Women’s Health Issues 26:6 (November-December 2016), pp. 595-601. https://www.whijournal.com/article/S1049-3867(16)30169-4/abstract; Nadia Tabatabaeepour et al., “Impact of prenatal substance use policies on commercially insured pregnant females with opioid use disorder,” Journal of Substance Use & Addiction Treatment 140 (September 2022). https://www.jsatjournal.com/article/S0740-5472(22)00082-4/fulltext.

[32]. Meghan Boone and Benjamin J. McMichael, “State-Created Fetal Harm,” The Georgetown Law Journal 109:475 (2020-2021). https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/glj109&div=18&id=&page; Angélica Meinhofer et al., “Prenatal substance use policies and newborn health,” Health Economics 31:7 (July 2022), pp. 1452-1467. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hec.4518.

[33]. Caroline K. Darlington et al., “Outcomes and experiences after child custody loss among mothers who use drugs: A mixed studies systematic review,” Drug and Alcohol Dependence 251 (Oct. 1, 2023). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0376871623011821.

[34]. Walter, “They Followed Doctors’ Orders. Then Their Children Were Taken Away.” https://www.nytimes.com/2023/06/29/magazine/pregnant-women-medication-suboxonbabies.html; Walter, “Hospitals Gave Women Medications During Childbirth—Then Reported Them for Using Illicit Drugs.” https://revealnews.org/article/hospitals-gave-women-medications-during-childbirth-then-reported-them-for-using-illicit-drugs.

[35]. Ibid.

[36]. Ibid.; Agnel Philip et al., “The ‘death penalty’ of child welfare: In 6 months, some parents lose their children forever,” NBC News, Dec. 20, 2022. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/termination-parental-rights-neglect-children-rcna61439; Taleed El-Sabawi and Sarah Katz, “Deinstitutionalizing Family Separation in Cases of Parental Drug Use,” The Yale Law Journal 134 (March 28, 2025). https://www.yalelawjournal.org/forum/deinstitutionalizing-family-separation-in-cases-of-parental-drug-use.

[37]. Work et al. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37253899.

[38]. Child Welfare Information Gateway, “About CAPTA: A Legislative History,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2019. https://cwig-prod-prod-drupal-s3fs-us-east-1.s3.amazonaws.com/public/documents/about.pdf?VersionId=y7C6qleUR3mZJ_UJ5t_dnzCNfO6HPcPs.

[39]. Ibid., p. 1.

[40]. Chelsea Boyd, “Substance Use, Pregnancy, and Policy,” R Street Institute, Jan. 23, 2025. https://www.rstreet.org/research/substance-use-pregnancy-and-policy.

[41]. “Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act (CAPTA) Requirements Related to Newborns ‘Affected By Substance Abuse,’” National Advocates for Pregnant Women, last accessed March 24, 2025. https://www.pregnancyjusticeus.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/CAPTA-Recommendation-Chart_1.5.2021-1.pdf.

[42]. “Substance-Affected Infants: Additional Guidance Would Help States Better Implement Protections for Children,” United States Government Accountability Office, January 2018. https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-18-196.pdf.

[43]. Ibid.

[44]. Molly R. Siegel et al., “Fentanyl in the labor epidural impacts the results of intrapartum and postpartum maternal and neonatal toxicology tests,” American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 228:6 (June 2023), pp. 741.e1-741.e7. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0002937822021858#:~:text=Neuraxial fentanyl for labor analgesia,on the testing method used.

[45]. “How can Plans of Safe Care help infants and families affected by prenatal substance exposure?,” Casey Family Programs, Oct. 19, 2023. https://www.casey.org/infant-plans-of-safe-care.

[46]. Ibid.

[47]. Ibid.

[48]. “Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act of 2016 – P.L. 114-198,” Child Welfare Information Gateway, July 2016. https://www.childwelfare.gov/resources/comprehensive-addiction-and-recovery-act-2016-pl-114-198.

[49]. Ibid.

[50]. “Substance-Affected Infants: Additional Guidance Would Help States Better Implement Protections for Children.” https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-18-196.pdf; John Sciamanna, “Series Finds that No State Follows All of the CAPTA Requirements,” Child Welfare League of America, last accessed March 24, 2025. https://www.cwla.org/series-finds-that-no-state-follows-all-of-capta-requirements; Margaret H. Lloyd Sieger and Rebecca Rebbe, “Variation in States’ Implementation of CAPTA’s Substance-Exposed Infants Mandates: A Policy Diffusion Analysis,” Child Maltreatment 25:4, (May 5, 2020), pp. 457-467. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1077559520922313.

[51]. “Introduction to Legal Mapping,” ChangeLabSolutions, last accessed April 21, 2025. https://www.changelabsolutions.org/product/introduction-legal-mapping.

[52]. “Substance Use During Pregnancy and Child Abuse or Neglect: Summary of State Laws,” Legislative Analysis and Public Policy Association, October 2022. https://legislativeanalysis.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Substance-Use-During-Pregnancy-And-Child-Abuse-Or-Neglect-Summary-of-State-Laws.pdf; Lloyd Sieger and Rebbe. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1077559520922313; Alexander D. McCourt et al., “Development and Implementation of State and Federal Child Welfare Laws Related to Drug Use in Pregnancy,” Milbank Quarterly 100:4 (December 2022), pp. 1076-1120. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36510665; Margaret H. Lloyd et al., “Planning for safe care or widening the net?: A review and analysis of 51 states’ CAPTA policies addressing substance-exposed infants,” Children and Youth Services Review 99 (April 2019), pp. 343-354. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0190740918309848.

[53]. Loren Siegel, “Report: The War on Drugs Meets Child Welfare,” Drug Policy Alliance, 2021, p. 5. https://uprootingthedrugwar.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/uprooting_report_PDF_childwelfare_02.04.21.pdf.

[54]. Neb. Rev. Stat. § 28-457, Neb. Rev. Stat. § 28-707; Kan. Admin. Regs. § 30-46-10.

[55]. “NH’s Plan of Safe Care Guidance Document,” Northern New England Perinatal Quality Improvement Network, Aug. 15, 2019. https://www.nnepqin.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/6-NH-POSC-Guidance-Document-8-15-19.pdf; Nev. Admin. Code § 449.947; NM Stat § 32A-4-3; NM Admin. Code § 8.10.5.7; NM Ann. Stat. § 32A-3A-13.

[56]. Plan of Safe Care-Newborns, S.F. 79, 67th Leg., Gen. Sess. (Wyo. 2023). https://wyoleg.gov/Legislation/2023/SF0079; “NH’s Plan of Safe Care Guidance Document.” https://www.nnepqin.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/6-NH-POSC-Guidance-Document-8-15-19.pdf.

[57]. “Substance-Affected Infants: Additional Guidance Would Help States Better Implement Protections for Children.” https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-18-196.pdf.

[58]. Tenn. Code Ann. § 39-13-107; “Work Aid 1: CPS Categories and Definitions of Abuse/Neglect,” Tennessee Department of Children’s Services, August 2024. https://files.dcs.tn.gov/policies/chap14/WA1.pdf.

[59]. IN Code § 31-34-1-12; IN Code § 31-34-1-13.

[60]. Susan Scutti, “21 million Americans suffer from addiction. Just 3,000 physicians are specially trained to treat them,” AAMC News, Dec. 18, 2019. https://www.aamc.org/news/21-million-americans-suffer-addiction-just-3000-physicians-are-specially-trained-treat-them.

[61]. Miles Meline, “Fears of Family Separation Deter Parents With Substance Use Disorder From Getting Needed Care,” Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics, July 23, 2024. https://ldi.upenn.edu/our-work/research-updates/fears-of-family-separation-deter-parents-with-substance-use-disorder-from-getting-needed-care.

[62]. Margaret H. Lloyd Sieger et al., “Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act, family care plans and infants with prenatal substance exposure: Theoretical framework and directions for future research,” Infant and Child Development 31:3 (Feb. 3, 2022). https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10823434.

[63]. Layal Bou Harfouch, “Unreliable drug tests shouldn’t be used to separate mothers from their newborns,” Reason Foundation, Nov. 13, 2024. https://reason.org/commentary/unreliable-drug-tests-shouldnt-be-used-to-separate-mothers-from-their-newborns; Shoshana Walter, “She Ate a Poppy Seed Salad Just Before Giving Birth. Then They Took Her Baby Away,” The Marshall Project, Sept. 9, 2024. https://www.themarshallproject.org/2024/09/09/drug-test-pregnancy-pennsylvania-california.

[64]. Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act of 2016 – P.L. 114-198.” https://www.childwelfare.gov/resources/comprehensive-addiction-and-recovery-act-2016-pl-114-198; Lloyd et al. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0190740918309848.

[65]. “Substance-Affected Infants: Additional Guidance Would Help States Better Implement Protections for Children.” https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-18-196.pdf.

[66]. “The Serious Consequences of Failure to Report Child Abuse,” Mandated Reporter, last accessed March 18, 2025. https://mandatedreporter.com/blog/the-serious-consequences-of-failure-to-report-child-abuse.

[67]. Bruzelius et al. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0955395924000653?via=ihub; Faherty et al. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2755304; Angelotta et al. https://www.whijournal.com/article/S1049-3867(16)30169-4/abstract; Tabatabaeepour et al. https://www.jsatjournal.com/article/S0740-5472(22)00082-4/fulltext.

[68]. Krans et al. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/add.15582; Hall et al. https://www.jsatjournal.com/article/S0740-5472(16)30153-2/fulltext.

[69]. Rebecca Stone, “Pregnant women and substance use: fear, stigma, and barriers to care,” Health & Justice 3:2 (Feb. 12, 2015). https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s40352-015-0015-5.

[70]. Ibid.; Davida M. Schiff et al., “‘You have to take this medication, but then you get punished for taking it:’ lack of agency, choice, and fear of medications to treat opioid use disorder across the perinatal period,” Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 139 (August 2022). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0740547222000472; Christine Bakos-Block et al., “Experiences of Parents with Opioid Use Disorder during Their Attempts to Seek Treatment: A Qualitative Analysis,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19:24 (Dec. 11, 2022). https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/19/24/16660.

[71]. Meinhofer et al., “Parental drug use and racial and ethnic disproportionality in the U.S. foster care system.” https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0190740920308318; Atkins and Durrance. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S019074092100270X?via=ihub.

[72]. Caroline K. Darlington et al., “Outcomes and experiences after child custody loss among mothers who use drugs: A mixed studies systematic review,” Drug and Alcohol Dependence 251 (Oct. 1, 2023). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0376871623011821.