Messages Underpinning Backlash to U.S. Harm Reduction Policy

Author

Table of Contents

- Executive Summary

- Introduction: Harm Reduction and the Evolving Opioid Crisis

- Methods

- Messages Underpinning Opposition to Harm Reduction

- Countering Opposition with Evidence

- Conclusion

Media Contact

For general and media inquiries and to book our experts, please contact: pr@rstreet.org

Decades of research demonstrate that harm reduction programs are beneficial to individuals and communities and represent an important part of a comprehensive approach to mitigating the risks of drug use.

Executive Summary

The U.S. overdose crisis continues to take tens of thousands of lives annually. Although fatalities have declined from their peak a few years ago, overdose remains a serious public health problem. Research shows that much of this progress in reducing overdose deaths is not a result of increased criminalization and interdiction efforts but, instead, is related to the past decade’s expansion of a pragmatic and life-saving approach to drug use known as harm reduction.

However, in recent years, harm reduction has faced rising backlash, with a number of states and local communities taking steps to repeal or impose restrictions on syringe services programs (SSPs) and others blocking the authorization of overdose prevention centers (OPCs). In this study, we identify several key messages underpinning opposition to harm reduction and examine the data related to these concerns.

Our research uncovered four main messages used by lawmakers, citizens, and advocates in their opposition to harm reduction:

- Harm to communities

- Harm to individuals

- Ideological disapproval of “enabling” individuals to use drugs

- Ideological disapproval of “sending mixed messages” about the legality and morality of drug use

Despite the current pervasiveness of these types of messages, they are not supported by evidence or aligned with real-world outcomes. First, when implemented according to evidence-based recommendations, harm reduction programs are not harmful to individuals or communities. In many cases, such programs benefit everyone by reducing infectious disease transmission, providing resources for safe needle disposal, saving taxpayer money, and preventing overdose deaths. Furthermore, the belief that harm reduction enables drug use is not supported by evidence. In reality, individuals who use harm reduction services are more likely to engage in treatment and stop using drugs. Finally, while the concern about sending mixed messages cannot be refuted by evidence, proponents of harm reduction emphasize that government support of harm reduction does not condone illicit drug use but rather provides people with the resources they need to protect their lives and health, even if they continue to engage in risky or illegal behaviors.

Because the messages underpinning harm reduction opposition are not consistent with the evidence on the effects of these programs, we recommend that lawmakers avoid misidentifying the approach as the cause of problems resulting from social, economic, and treatment gaps. Instead, when contemplating legislation related to harm reduction, lawmakers should consider the decades of research that show the benefits of these programs for individuals and communities and see them as an important part of a comprehensive approach to illegal drug use that includes prevention and treatment.

Introduction: Harm Reduction and the Evolving Opioid Crisis

Overdose deaths have been climbing in the United States for decades. The crisis peaked in 2022 and 2023, with more than 111,000 annual overdose deaths, roughly 80,000 of which involved opioids. In response to these rising deaths, a growing number of policymakers across the United States have turned to a time-tested and evidence-based approach to saving the lives of people who use drugs: harm reduction.

Harm reduction is grounded in the belief that some people will always engage in risky behavior. By acknowledging that abstinence is not a desired or realistic goal for everybody, harm reduction meets people who use drugs where they are to empower them “with the choice to live healthy, self-directed, and purpose-filled lives.”

This approach is an important strategy in the context of prohibition, as many of the dangers attributed to illegal drug use are actually the result of criminalization and prohibition. For example, prohibition encourages the production of increasingly dangerous substances because the smaller relative size of more potent products makes them easier to traffic undetected. Similarly, drug criminalization and paraphernalia laws create conditions that make individuals more likely to inject quickly, alone, and in unsafe environments, as well as discourage them from calling 911 during an overdose to avoid charges.

More than 30 years of evidence demonstrates that harm reduction interventions improve health and save lives. For example, syringe services programs (SSPs) reduce the risk of disease transmission and provide overdose reversal training. In addition, SSPs and other community organizations—from addiction treatment centers to shelters for unhoused people—prevent overdose deaths by distributing tools like overdose reversal medication and fentanyl test strips (FTSs). The stigma-free provision of services, in turn, allows organizations to provide a safe point of connection to social and treatment services.

Recognizing the need for these types of interventions, at least 16 states decriminalized FTSs between January 2022 and mid-2023 (the peak of the overdose crisis). And to ensure that FTSs can be used without negative consequences, as of December 2023, 45 states and Washington, D.C. either had no laws prohibiting the possession of drug paraphernalia or had exempted FTS possession or use from those laws. Additionally, between 2014 and 2019, the number of states authorizing SSPs nearly doubled, with 14 states newly authorizing the programs. During that same period, 12 states reduced legal barriers to SSPs.

Many experts agree that these and other harm reduction–positive policies helped turn the tide on the overdose crisis. Furthermore, supply-side interventions like increased criminalization likely had little to do with the progress, as the decline in deaths began before major increases in such policies. Indeed, in 2024, drug fatalities had fallen to roughly 80,000—significant progress from just a few years earlier but still unacceptably high and continuing to climb in some communities. As such, medical and public health experts caution that to sustain and build on this progress, governments must continue to expand harm reduction, not restrict or defund it.

Nonetheless, there has been a growing backlash to harm reduction. At the policy level, this is playing out across the political spectrum and in states in practically every part of the country. For example, in 2024, Nebraska Governor Jim Pillen vetoed a bill that would have allowed communities in the state to authorize SSPs. That same year, Idaho repealed SSP authorization, and Pueblo, Colorado, circumvented state preemption laws and prohibited SSPs—an action that was later overturned in the courts. Similarly, in 2025, Oregon lawmakers introduced legislation to increase regulations on SSPs. Even California is experiencing limitations; San Francisco’s recent “Breaking the Cycle” executive directive has added a requirement that programs provide counseling or direct connections to treatment and other services in order to distribute safe injection supplies.

Given this shifting political landscape, this paper identifies the discourse underpinning the opposition to harm reduction to better understand the concerns voiced by lawmakers, community members, and interested organizations. By enhancing our understanding of these concerns, we can better educate decision-makers and influence policy with evidence-based, priority-driven solutions.

Methods

To better understand the recent backlash against harm reduction, we identified key messages being used to actively oppose the approach in state legislatures. We did so by examining testimony and lawmaking discourse associated with harm reduction–related bills in the past two-and-a-half years.

We used a purposive sampling approach to identify relevant legislation introduced in a variety of states with diverse political landscapes during the defined time period—since 2023, when we began subjectively noticing active backlash. Using legislation trackers such as LegiScan and POLITICO Pro, we searched for bills introduced during the 2023, 2024, or 2025 state legislative seasons that related to the authorization, expansion, or restriction of SSPs or overdose prevention centers (OPCs). We limited our search to these two types of harm reduction programs because these are the areas where we have witnessed pushback in recent years and because they both provide direct services within communities. We identified a total of 48 bills in 19 states that met these initial criteria.

SSPs and OPCs Explained

SSPs are organizations where individuals can obtain and dispose of sterile injection equipment. While their primary role since their establishment in the 1980s has been to reduce the transmission of infectious diseases such as HIV and hepatitis C (HCV), SSPs often also provide overdose prevention education, distribute overdose-reversal medication, provide drug-checking equipment, offer testing for HIV and HCV, connect participants to social and health services, and more. OPCs—also known as safe consumption sites or supervised injection facilities—are locations where individuals can self-administer pre-obtained substances in a setting where trained professionals are on site to respond to overdoses. As the name implies, the primary function of these sites is to prevent overdose fatalities. However, they also typically provide wound care, sterile injection equipment, education about overdose and disease prevention, and connection to services.

Because this study is focused on the messages underpinning opposition to harm reduction, we narrowed the original sample to those bills that had, at a minimum, been referred to and heard in a committee. This ensured the possibility of including public testimony, debate, and other legislative records.

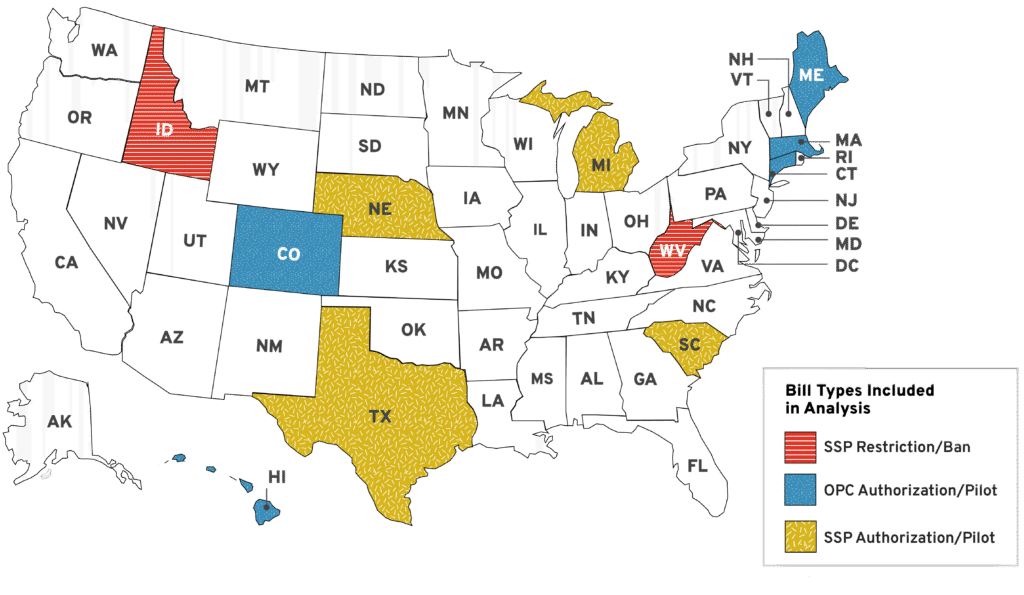

Once these bills were identified, we used a convenience sampling approach to gather sources of discourse and, specifically, messages used by opponents of harm reduction to justify their position. We accessed publicly published written testimony, written transcripts, and recorded audio/video of hearings and floor debates, as well as written summaries of legislative happenings. We were able to identify these sources for 14 bills in 11 states (Figure 1).

Figure 1: States and Bill Types Included in Analysis

We analyzed these sources to identify key arguments in opposition to harm reduction, operationalized as individuals speaking in favor of increased restrictions on or repeals of harm reduction programs (SSPs or OPCs) or those speaking against the authorization or expansion of harm reduction programs (SSPs or OPCs). We coded these sources to identify the answers to the following questions:

- What are the arguments against harm reduction?

- Who is speaking in opposition to harm reduction in states?

We organized the resulting data into themed categories. To identify the type of messages consistently being leveraged in arguments against harm reduction, we identified themes that came up across issues, in multiple states, and over time.

Opponents of harm reduction consistently included individual community residents, law enforcement organizations, religious organizations, think tanks, and lawmakers. In addition, a handful of states heard oppositional testimony from less common sources. In Nebraska, for example, a representative from the Department of Health and Human Services spoke against SSPs, making arguments consistent with other opponents. In Colorado, the Greater Harlem Coalition—an out-of-state community organization—testified in opposition to OPCs, again echoing the concerns heard from others. Finally, legal experts and one state’s public health department testified against OPCs in many instances, but because their concerns were limited to the federal status of these sites, they were excluded from our analysis.

Messages Underpinning Opposition to Harm Reduction

Our analysis of the testimony, hearings, and debates revealed that many opponents were using the same messages to argue against harm reduction across states and over time. With the exception of concerns about the federal (il)legality of OPCs (which we excluded from this analysis) and some state-specific complaints about individual programs, the same broad arguments were commonly used to oppose SSPs and OPCs. We identified two general categories of messages: increased (unintended) harms and ideological disapproval.

Increased Harms

The first major concern that came up repeatedly is the notion that harm reduction programs lead to unintended negative consequences. These can be further broken down into fears about harm to the community and fears about harm to participants.

Numerous sources we reviewed in testimony and floor debate comments, expressed by a range of individuals from private citizens to lawmakers, voiced concerns about the effects of SSPs and OPCs on communities. Opponents to harm reduction argued that such programs degrade their neighborhoods and reduce public safety by increasing local crime, public drug use, and syringe litter. Some individuals directly referenced the increase of such problems in states like Oregon and California, which have embraced SSPs, even though the issues are not necessarily a result of harm reduction efforts. For example, at an Idaho hearing on legislation to repeal the state’s SSP authorization, one citizen claimed that such programs would transform the state and had already led to increased homelessness and public intoxication in the streets of Boise, saying:

What you’re gonna build is Oregon, California, and if you don’t stop it here and stop it now, it just gets worse. I mean, imagine where this is happening. It’s downtown Boise area, and what do you see in Boise now? You see people laying [sic] on the street.

The other type of unintended consequences messaging we saw emphasized the idea that OPCs and SSPs could directly endanger participants rather than help them. This fear was expressed in several different ways, with harm reduction opponents claiming that SSPs increase risk-taking, encourage people to begin injecting drugs or try illegal substances, and increase the likelihood of overdose death, often citing economic studies that have been broadly criticized by public health experts.

Ideological Disapproval

The second area of concern expressed by opponents of harm reduction was a fundamental disagreement with the approach. This, too, fell into two distinct, but related, categories. The first of these is the perception that by authorizing harm reduction, the state is giving permission—implicit or explicit—to engage in illegal behavior. This disapproval was echoed by numerous lawmakers during hearings in Texas and South Carolina, with assertions that the approach sends mixed messages by condoning illegal and harmful behavior. For example, one Texas representative asked, “Are we sending mixed messages, saying drug use is illegal and then we’re providing the tools to do it?”

Another nearly ubiquitous critique of harm reduction focused on the approach’s goal of meeting people where they are and giving them the resources and information to stay as safe as possible without requiring or necessarily encouraging abstinence. Opponents expressing this concern claimed that the approach enables drug use instead of promoting treatment. This complaint was voiced in a variety of ways. For example, opponents in Colorado claimed that OPCs would not reduce the demand for drugs, whereas those in Massachusetts argued that harm reduction fails to address the root causes of substance use disorder and the state should instead focus on expanding civil commitment to substance use disorder treatment. A Texas lawmaker questioned whether taxpayers should be prioritizing a practice that “enables” drug use over treatment, setting up the argument that harm reduction and treatment operate in opposition to one another, rather than in cooperation.

Countering Opposition with Evidence

The anti–harm reduction messages that we identified in this study have actively influenced policy in recent years, driving backlash against the approach. Of the oppositional messages identified in this study, only one—that authorizing harm reduction sends mixed messages and constitutes state sanctioning of illegal behavior—is not directly refutable with evidence. However, advocates of harm reduction would argue that it is not an approval of drug use so much as an acknowledgment that some people engage in risky behavior and that those people retain the right to stay as safe and healthy as possible.

The other three oppositional messages we identified in this study can be countered by empirical evidence derived from decades of research on SSPs in an extremely wide variety of geographic and cultural contexts and emerging evidence on OPCs from Europe, Canada, Australia, and the United States. Below, we highlight evidence-based talking points that lawmakers can reference when advocating for harm reduction policy.

Harm Reduction Benefits Participants

The primary goals of SSPs and OPCs are disease and overdose death prevention, respectively. The organizations are exceptionally good at meeting these aims and at driving secondary medical and social benefits for their participants.

By providing participants with sterile injection equipment and knowledge about how to stay as safe as possible, SSPs have been shown to reduce the transmission of HIV and HCV by approximately 50 percent. In addition, SSPs reduce other injection-related complications, including soft-tissue infection and endocarditis. Moreover, because the programs serve as trusted touchpoints and safe spaces for stigma-free care, it is not surprising that individuals who engage with SSPs are five times more likely to enter treatment and three times more likely to quit using drugs altogether.

Although there is less data on OPCs than on SSPs, available research suggests that they offer similar benefits. In addition to preventing overdose deaths, OPCs are associated with a reduction in HIV and HCV transmission. Several studies have shown that engagement with the sites increases treatment uptake and safer injection practices—for example, people are less likely to rush injections or share needles. Indeed, data from two OPCs in New York City support these findings. In the sites’ first year of operation, approximately 75 percent of participants connected with other services (e.g., social and medical) through the organization, and staff intervened during 636 overdoses to prevent injury or death.

Harm Reduction Is Not Enabling

The argument that SSPs, OPCs, and other harm reduction interventions enable drug use is inaccurate and problematic. First, as noted in the previous section, harm reduction has been repeatedly shown to not encourage drug use. Rather, participation in harm reduction programs such as SSPs and OPCs is associated with a significantly greater likelihood of entering treatment and stopping illicit drug use. This demonstrates the important role these programs play in connecting with vulnerable individuals who are otherwise isolated from healthcare systems as well as those who are actively seeking to improve their health.

Because harm reduction programs connect people who use drugs with treatment when appropriate and encourage healthier behaviors in general, they should not be seen or treated as a barrier to reducing demand. Rather, they fill an important space as one part of a comprehensive strategy that also includes prevention and treatment.

Harm Reduction Can Benefit Communities

According to the vast majority of available research, SSPs and OPCs do not endanger communities as many opponents to the approach suggest in this study. In fact, the programs may have a net benefit to communities on some metrics like syringe litter and public drug use.

First, and perhaps most important to lawmakers and community residents, research conducted on a variety of locations since the early 2000s has found that the presence of harm reduction programs is not associated with increases in crime. For example, a Baltimore study found no association between the opening of an SSP and crime rate trends in the surrounding neighborhood. Similarly, research from Harlem, New York, found no consistent differences in resident-reported violence between individuals living near SSPs and those living further from the programs.

A study comparing a decade of neighborhood crime trends before and after opening an unsanctioned OPC to crime trends in neighborhoods without an OPC found that documented criminal activity fell in the surrounding area after the OPC’s opening. In addition, research comparing neighborhood rates of crime and civil disorder before and after the implementation of two OPCs in New York City (which were opened on Nov. 30, 2021, at preexisting SSP sites) found a 33 percent reduction in medical 911 calls, a significant decrease in crime-related 911 calls, and no significant change in emergency and nuisance calls or in violent or property crimes. A second study on these sites found a significant increase in property crimes within 1,000 feet of an OPC in Washington Heights but no change in property crime around an East Harlem site, which suggests that the OPC site location may be unrelated to increased property crime. Meanwhile, neither site was associated with changes in violent crime in the surrounding areas.

Not only do these programs not harm their surrounding neighborhoods, but they can contribute to safer, healthier communities. For example, SSPs have been shown to reduce syringe litter in communities from Miami to San Francisco. In addition, the proper disposal of used needles—which SSPs facilitate through direct collection and by distributing sharps containers—reduces the odds of needle-stick injuries to children, sanitation workers, city employees, and others. Consequently, law enforcement has increasingly become an ally for SSPs, recognizing that the organizations fill an important gap in services without creating or exacerbating public safety issues, and sometimes even improving them.

Furthermore, by providing individuals with a safe, sanitary place to consume substances off the street, OPCs may reduce the visibility of drug use in neighborhoods. A systematic review of studies conducted in the United States, Canada, Australia, and Europe found that OPCs were consistently associated with reductions in public injection. A study of the unsanctioned SPOT program in Boston, Massachusetts, found that the number of “over-sedated individuals observed in public” fell by 28 percent after the program opened. Additionally, research from a New York City OPC estimated that in their first year of operation, the sites prevented 39,000 incidences of public drug use.

Finally, by helping participants in the ways explained in previous sections, both OPCs and SSPs benefit communities as a whole. More than 40 percent of people in the United States—roughly 125 million individuals—have lost someone to a drug overdose. Thus, preventing overdose deaths also reduces the suffering experienced by friends and family of those who use drugs. Furthermore, by reducing disease transmission among participants, SSPs and OPCs also reduce the risk of an outbreak in the broader community. In fact, after West Virginia greatly restricted SSPs, communities in which the SSP organizations shuttered their doors experienced spikes in HIV infections.

The sites also benefit communities beyond their participants by saving taxpayer money. The prevention of infectious disease, treatment of injection-site wounds, reversal of overdoses, and other services can reduce participants’ need to engage with emergency medical services or receive long-term care for a chronic disease.

Despite this evidence, harm reduction faces a real barrier in its perceived impact on community safety. Reports from community members in the neighborhoods around New York’s OPCs—evidenced by Greater Harlem Coalition’s testimony in Colorado—are mixed, with some people claiming increases not just in drug use but also in drug selling. It is challenging to parse these perceptions from the empirical reality in these communities, as they are affected by a range of factors beyond the presence of harm reduction programs. For example:

- Local socioeconomic conditions—such as a lack of affordable housing and subsequent increasing homelessness—can lead to more public drug use and/or syringe litter that is then attributed to the presence of a harm reduction program.

- Many communities with harm reduction programs have complex historical and cultural relationships to drug use and the drug war.

As such, lawmakers and harm reduction organizations must work closely with communities to ensure that residents are not only safe but also continue to feel comfortable and welcome in their neighborhoods.

Conclusion

Harm reduction has played an important role in combating the overdose crisis in the United States, as a growing number of regionally and politically diverse states have authorized these interventions over the past decade. Indeed, experts agree that harm reduction organizations have helped cut annual overdose deaths by roughly 20 percent by increasing access to naloxone and drug-checking equipment, providing life-saving overdose reversal education and services, and acting as an essential point of connection to a range of medical and social services.

Despite these gains, harm reduction has been met with growing backlash in recent years, with state legislators seeking to repeal harm reduction authorizations, restrict existing programs, and push back on efforts to permit new interventions. Our research revealed that opponents of harm reduction primarily cite concerns that the approach harms communities and individuals and contradicts the government’s ideological opposition to illicit drug use. Most of these concerns, however, are unfounded, as decades of research have demonstrated benefits such as reductions in syringe litter; decreases in the spread of infectious disease and other injection-related health complications; safe connections to services and treatment; reductions in overdose death risk; taxpayer savings; and more. Furthermore, many of the perceived harms that are attributed to harm reduction may be the result of other issues, including growing economic instability and a lack of affordable housing, both of which may lead to increased homelessness and increased visibility of substance use and intoxication.

Thus, while it is important that all stakeholders recognize the concerns that opponents express about harm reduction, they must avoid scapegoating the approach for problems that may be attributable to criminalization, economic disenfranchisement, or lack of treatment resources. By not blaming the approach for general social problems, policymakers can turn their attention to solutions that truly target the community issues driving many of these concerns. And by acknowledging the decades of evidence supporting harm reduction, lawmakers can both uphold individuals’ right to protect their health and lives and advance strategies that benefit those who use drugs and strengthen the communities they call home.