Lessons from the States on Entitlement Reform

Table of Contents

Media Contact

For general and media inquiries and to book our experts, please contact: [email protected].

Executive Summary

Social Security has operated at a deficit for the past 14 years and is currently projected to deplete its asset reserve by 2034. State governments faced a similar type of challenge in the 2010s after two recessions decimated public pension plan assets and strained government budgets. As pension funding levels declined and costs increased, lawmakers responded by approving a mix of contribution increases and benefit reductions that stabilized these systems for public workers, retirees, and taxpayers. Every state has enacted at least one pension reform since 2009. There is still time to address the Social Security deficit by making benefit reductions or payroll tax increases and the sooner Congress acts, the smaller the change needs to be. Unfortunately, there is no contemporary playbook to guide federal lawmakers on making these kinds of tough decisions.

In this paper, we provide a brief overview of the challenges facing Social Security as well as those that faced state and local pension programs following the Great Recession. We explore potential reform options for Social Security, drawing comparisons with the reform options that were implemented at the state level.

With an eye toward offering a pathway forward for Congress, we look at how state lawmakers managed changes to benefits and contributions, which required shared sacrifice and still received broad support.

Our review finds that strong reforms were commonly approved in states governed by Democrats and Republicans alike. We found that the most impactful reforms—including those that applied to retiree benefits—were commonly enacted as part of a package requiring shared sacrifice across constituencies, and in states where Democrats and Republicans shared the political risk associated with reform. By following a similar approach with Social Security, lawmakers have the opportunity to both overcome the program’s long-standing reputation of being the third rail of American politics and strengthen the system supporting millions of Americans who are retired or disabled.

Introduction

Social Security is on track to deplete its reserves by 2034, having operated at a deficit for its 14th consecutive year. The reserves are currently being used to backfill annual deficits, ensuring that full benefits are paid each year. Once all of the assets in the reserve are gone, incoming payroll taxes would only be able to support around 80 percent of the projected benefit payments, resulting in benefit cuts for millions of Americans. This scenario can be avoided if Congress approves legislation that reduces projected benefit payments or increases projected payroll taxes. The sooner Congress acts, the smaller these changes need to be.

The last time Congress approved a major overhaul of Social Security was four decades ago in 1983. At the time, the trust fund reserves were set to be exhausted within one year, so President Ronald Reagan and congressional leaders struck a deal that accelerated the implementation of a previously enacted payroll tax increase, delayed a cost-of-living adjustment (COLA), and increased the retirement age, among other changes. As a result of that legislation, Social Security operated at a surplus for the next three decades, which built up the balance that is now being depleted as the baby boomer generation (those born between 1946 and 1964) retires.

While similar to the situation in 1983, today’s shortfall is larger in magnitude, and Congress’s action is long overdue. A variety of reform options could help solve the problem, and experts across the political spectrum have crafted their preferred approaches. The question for Congress is one of political will. Sustainable Social Security reform will likely require a combination of tax increases and benefit cuts that will be unpopular with voters, and unfortunately there is no contemporary playbook in Washington to guide federal lawmakers in making these decisions. The answer, however, may come from state legislatures.

In the aftermath of the Great Recession, which put severe pressure on state public pension plans and government budgets, lawmakers responded by enacting politically challenging reforms that impacted public workers, retirees, and taxpayers. These reforms did not eliminate the pension problem—in fact, state and local pensions are estimated to remain underfunded by more than $1 trillion—but they did put states in a stronger position to pay down that deficit over time.

As we document in this report, although the design and purpose of Social Security and public employee pensions are fundamentally different, the approach that many states took to reform pensions could serve as a model for members of Congress seeking to improve the financial outlook of Social Security. Specifically, we look at solutions requiring shared sacrifice across different constituencies and shared political risk among lawmakers.

First, we provide a brief overview of the challenges facing Social Security and possible solutions, focusing on policy adjustments that were approved at the state level. With an eye toward offering a pathway forward for Congress, we then summarize the challenges that faced public pensions following the Great Recession and explore how lawmakers responded from a national perspective. Next, we look to a subset of states that approved COLA reductions and review the political composition of those states and the content of the legislation in order to draw critical lessons from these policy shifts.

Social Security has a longstanding reputation as a third rail in politics, meaning that the issue is so politically charged that lawmakers avoid attempting to solve the problem for fear of damaging their future political careers. But, as evidenced in the state pension reform packages of the last 15 years, such a challenge can be overcome when both sides prioritize problem solving over partisanship.

Lessons from the States on Entitlement Reform

Lawmakers have an opportunity to overcome the long- standing reputation of Social Security as the third rail of American politics and strengthen the system supporting millions of Americans who are retired or disabled.

Social Security Overview and Key Challenges

The federal Social Security system and the public pension plans operated by state and local governments are important sources of retirement income for millions of Americans. Both provide guaranteed benefits to retirees that are financed through contributions from workers, employers, and—for pension plans in particular—investment income. While the two programs share some similarities, there are also key differences in the design and operation of the two systems as well as the nature of the challenges facing each.

Overview

Social Security is a retirement and disability plan covering nearly all Americans. According to the 2023 Social Security trustees report, 66 million individuals were collecting benefits—57 million via “old age and survivors insurance” and 9 million under “disability insurance.” To pay for these benefits, 181 million workers and their employers contribute to Social Security through payroll taxes at a rate of 12.4 percent for the first $168,600 a worker makes in a year, divided evenly between workers and employers.

The program operates largely on a pay-as-you-go basis, meaning that annual contributions are intended to cover the annual cost of benefits. In years when contributions exceed benefits, the surplus is set aside in a trust fund where it is invested in special issue treasury bonds. In years when the benefit payments exceed the contributions, trust assets are redeemed to cover the deficit.

Key Challenges

Social Security ran cash flow surpluses each year from 1984 to 2009 and accumulated a $2.5 trillion asset reserve in that time. Then the demographics shifted, as the baby boomer generation began to retire at a faster rate than the workforce could grow, leading the Social Security program to operate at a cash flow deficit since 2010. In 2022, the deficit stood at $88 billion.

Despite these persistent deficits, the asset reserve continued to grow due to interest earnings, peaking at $2.9 trillion in 2020. Starting in 2021, however, interest earnings were unable to cover the shortfall, and reserve assets were used to make benefit payments. As a result, reserve assets began to decline and are projected to reach zero by 2034. At that point, the system under current law will only be permitted to pay benefits in an amount equal to the taxes collected, which translates to cuts of up to 20 percent for many of our country’s most vulnerable populations.

Avoiding this outcome in the near term and eliminating the long-term shortfall over time may be one of the greatest political challenges facing Congress in generations. After all, Americans of all political stripes have long opposed their own taxes being raised or benefits being cut. But Social Security experts have repeatedly recommended these exact steps to shore up the health of the system.

Social Security Policy Options

Each year, the U.S. Social Security Administration (SSA) publishes an extensive list of potential policy changes and an estimate of the financial impact of each. The policy changes fall into eight categories, and the financial impacts measure what percentage of the long-term actuarial funding shortfall is eliminated (or increased) by the change. The 2023 report includes 137 potential adjustments to things like benefit levels, payrolls taxes, and COLAs. Of these options, 26 are estimated to eliminate at least 50 percent of the shortfall.

As we discuss later in this report, there are two types of reform that could make a substantial impact on the long-term financial outlook of Social Security and that have been widely used in the context of public pension reform: COLA reductions and payroll tax increases. The SSA estimates that a 1 percentage point reduction in the COLA could eliminate 54 percent of the long-term actuarial shortfall, whereas a 4 percentage point increase in the payroll tax would fully eliminate the shortfall.

COLA Reductions

COLAs are intended to help ensure that retirement benefits maintain their purchasing power over time. The Social Security COLA varies each year and is tied to an inflation metric. Over the past decade, the annual COLA has ranged from 0 percent to 8.7 percent; in 2023, it was 3.2 percent. Importantly, COLAs compound year over year, which means each annual increase becomes part of the base benefit in future years.

For example, consider a retiree with a $1,000 monthly base benefit. A 3 percent COLA in 2023 would raise the benefit by $30 to $1,030. For 2024, the base benefit becomes $1,030, and another 3 percent COLA would generate a $31 increase to $1,061. These increases continue to grow indefinitely as COLAs are granted. While compounding accelerates benefit growth, it would also create significant savings over time should there be a reduction in the COLA. R Street Policy Study No. 303 April 2024

While reducing the COLA would not result in a year-over-year reduction in payments received by beneficiaries, it would expose them to the effects of inflation. After all, COLAs are designed to keep the benefit in line with the cost of living. As a result, reducing the COLA is a challenging reform politically—particularly given the fact that one of the goals of Social Security is to serve as a safety net program for vulnerable populations. To account for this, some proposals look to balance this concern by maintaining full COLAs for lower-income beneficiaries, while eliminating COLAs for those with a higher income. While not as potent as an across-the-board cut, one such policy option has been projected to reduce the long-term shortfall by 36 percent.

Payroll Tax Increases

As described earlier, Social Security is primarily financed through a 12.4 percent tax on the first $168,000 a worker earns.16 As may be expected, this leaves two main levers for modifying the payroll tax: adjusting the rate while maintaining the existing cap or maintaining the existing rate while increasing the cap.

Both approaches have the potential to make a meaningful impact on the long- term shortfall. For example, the SSA estimates that raising the rate to 16.4 percent would fully eliminate the long-term shortfall. Similarly, though less effectively, removing the cap and applying the 12.4 percent rate to all wage and salary earnings would eliminate 70 percent of the shortfall.

Changing the tax rate, while potentially incredibly effective, is challenging to enact because payroll taxes are regressive, meaning that lower-income workers pay a higher share of their earnings in payroll taxes than high-income workers. A rate increase would exacerbate this effect. On the other hand, raising the cap and subjecting more income to taxation without a corresponding increase in benefits would mean higher income earners would be directly supplementing the benefits received by lower income workers. While some may see this option as equitable, it would further disaggregate Social Security from a social insurance plan, as conceived at its inception, and veer toward a welfare system. Raising the cap may also create incentives for employers of high-income workers to shift compensation from wages and salaries, which are subject to the tax, to retirement benefits, which are not.

With these reform options in mind, we turn to an overview of the state and local pension landscape in order to explore the legislative history of successful efforts to improve pension sustainability.

Public Pension Plans Overview and Policy Responses

Overview

State governments operate pension plans covering over 23 million active and retired teachers, police officers, firefighters, and other public employees. Most of these members participate in defined benefit plans, though a number of states have begun enrolling workers in other types of plans such as defined contribution or hybrid plans.

Defined benefit (DB) pension plans collect annual contributions from workers and their employers; invest those proceeds in a mix of equities, bonds, and alternative investments; and provide a guaranteed benefit to retirees based on a calculation that weighs years of service and final average salary. Many DB plans also provide COLAs that can increase the benefit level over time. These plans are most commonly available in the public sector, where 86 percent of workers have access to a DB plan, as opposed to the private sector, where DB plans are available to only 15 percent of workers.

Defined contribution (DC) plans, on the other hand, provide workers with a tax- preferred savings vehicle but no guaranteed benefit at retirement. Workers, and in some cases employers, contribute to the DC plan, with investments based on the preferences of the individual and the benefit at retirement dependent on the accumulated balance. Hybrid plans combine features from both DB and DC plans by providing a small guaranteed benefit while simultaneously contributing a portion to a DC plan.

In 2022, public pension plans reported $4.5 trillion in assets and $5.9 trillion in liabilities, leading to an overall 76 percent funded ratio—a common measure of pension funding that represents the percentage of plan liabilities that are covered by plan assets. Public plans collected $222 billion in contributions, with 77 percent of which came from taxpayers in the form of employer contributions or supplemental payments and 23 percent of which came from public workers. Comparatively, Social Security payroll taxes are split equally between employers and workers.

In terms of benefits, the public pension plans paid $257 billion to beneficiaries in 2022, which is $35 billion more than the amount collected through contributions. Cash flow deficits are common among pension plans, and while they need monitoring for signs of fiscal distress, overall, they do not pose the same risk of asset depletion as the current Social Security deficit. This is because pension funds are designed to rely on growth from investments in the market, which finance the benefits and regularly assume an average annual return of 6.9 percent. This is fundamentally different from Social Security, where asset reserves are invested in traditionally low-risk U.S. Treasury bonds, which have yielded an effective annual interest rate ranging from 2.4 percent to 3.8 percent over the past decade.

However, pension plans’ reliance on investment performance also comes with exposure to financial market risk and potential losses. With a strong economy fueled by the explosion of technological innovation and a surging housing market, state and local pension plans were fully funded in the early 2000s. But as the “dot com” bubble burst in 2003 and the housing market crashed in 2008, funding levels subsequently declined in the latter part of the decade. In 2008, pension assets fell by approximately 25 percent from their high in 2007.

The markets rebounded in the years that followed, but pension plan funding levels were slow to recover. The turmoil caused by the recessions revealed some of the poor decisions that were made while the plans were financially secure. For example, some states did not consistently make the full contribution that plan actuaries recommended to ensure long-term plan solvency, whereas others granted unfunded benefit increases to retirees. The negative impact of these decisions became more apparent once the plans became underfunded.

As pension funding levels declined, contribution requirements rose. Between 2000 and 2010, employer contributions from state and local governments increased from approximately $60 billion to more than $100 billion. These increases occurred as budgets were already strained by the recessions, so lawmakers also sought reforms that would require shared sacrifice from public workers, retirees, and taxpayers. The next part of this paper takes a closer look at these reforms and explores how a similar approach could provide federal lawmakers with a framework for addressing the impending Social Security crisis.

Policy Responses

In the wake of the financial crisis of 2008 and 2009, state lawmakers scrambled to stabilize their public pension plans in the 2010s. According to the National Association of State Retirement Administrators, every state has approved a reform to at least one of their pension plans since 2009. Public pension solutions occasionally took the form of new retirement systems for future employees, shifting from DB plans to hybrid, cash balance, or DC plans. These changes were politically controversial, often facing resistance from public employee workers and unions. Nevertheless, lawmakers in 12 states have approved legislation adopting these types of plans since 2009.

Meanwhile, most states relied on less splashy adjustments that increased contributions and reduced benefit levels while maintaining the underlying defined benefit structure. For example, employee contribution rates rose in 40 states and annual employer contributions grew from $100 billion in 2010 to $180 billion in 2020. On the other side of the ledger, 40 states adjusted benefit formulas in order to yield lower pension payments in the future, and 32 reduced COLAs.

In the context of reforming Social Security, the employee contribution increases and COLA reductions—particularly those that applied to the current generation of workers and retirees—are especially relevant because they required lawmakers to take actions that would improve the pension plans, but at a substantial political cost. The employees and retirees who bore the brunt of these types of reforms often objected to any cuts to their benefits or increases to their contributions. But it is these changes that generate the most immediate and effective results for state and local pension plans and that can provide a model for federal lawmakers looking to stabilize Social Security.

Appendices 1 and 2 include lists of the employee contribution increases and COLA reductions impacting current workers and retirees that were approved by state lawmakers between 2010 and 2022. To curate this list, we started with source information from the National Association of Retirement Plan Administrators (NASRA) research and removed changes that only impacted new hires, were approved by a pension board, or that automatically occurred due to existing policy that adjusted contributions or COLAs without further input from lawmakers.

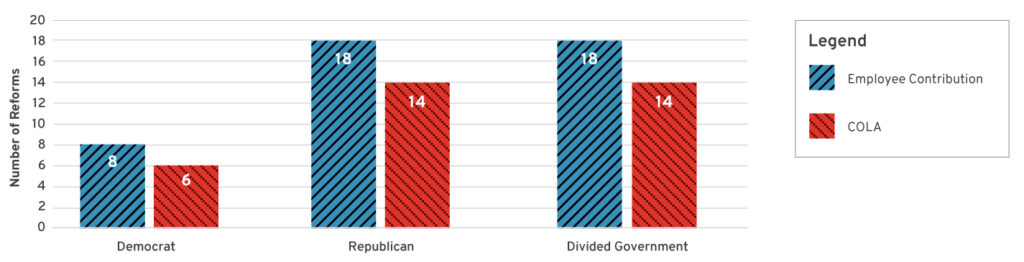

As shown in Figure 1, these types of changes to pension plans occurred in states controlled by Democrats, Republicans, and in states with shared political power. Some states made changes to more than one plan or made changes to the same plan over multiple years, so the total number of changes that occurred is higher than the number of states, with 44 contribution increases and 34 COLA reductions. Of the 78 total reforms to COLAs and contributions, 14 occurred in Democrat- controlled states, 32 in Republican-controlled states, and 32 in divided states.

Figure 1: Employee Contribution Increases and COLA Reductions by Control of State Government (2010-2022)

These numbers show that states controlled by Republicans or that had divided governments approved more than twice as many changes than states controlled by Democrats. Two factors likely explain this disparity.

First, Democrats controlled fewer state capitals during this time period. In any given year, each party has 50 opportunities to control a state capital. Over the 13 years from 2010-2022, there were 650 chances. Democrats fully controlled state governments 153 times compared to 281 instances for Republicans and 216 times in which the state government was divided. However, even when adjusting for the number of opportunities, Democrats still approved these changes at a lower rate, accounting for 19 percent of the reforms while controlling state government 24 percent of the time. By comparison, states controlled by Republicans and states that had divided governments accounted for the same share of the reforms—41 percent each—despite divided governments having fewer opportunities at 33 percent compared to 43 percent for Republicans.

A second factor that likely drove underperformance among Democrat-controlled states was the influence of public employee unions.38 These unions primarily support the Democratic party and are often opposed to changes to defined benefit plans that would negatively impact their members.39 Absent the constraint from union supporters, Republicans can more easily pursue adjustments DB plans or pursue more aggressive pension reforms like transitioning to a DC plan.

With that being said, there are other factors beyond political control that impact whether pension plan reforms occur, such as the financial health of the systems, and, in the case of COLA reductions, whether the plan has an automatic COLA to reduce in the first place. This review suggests that political party control did have a meaningful impact on the likelihood of pension plan reform. However, as we will demonstrate in the next section, bipartisan support was still common when enacting COLA reductions, even in states controlled by a single party.

Legislative Review: Cost-of-Living Adjustments

Like Social Security, most public pension plans provide an automatic, formula- driven COLA adjustment that helps mitigate the effect of inflation and maintain the purchasing power of a retiree’s benefit over time. These could come in the form of an automatic annual adjustment of a set percentage, an increase tied to the consumer price index, or an increase that occurs if certain funding or investment performance conditions are achieved. Automatic COLAs are in place in 40 states; in the remaining 10 states, they are granted on an ad-hoc basis, meaning the legislature would need to act each year.

COLA reductions are a common policy response because they provide the only viable option to reduce plan liabilities in the near term. The laws governing pension plans vary by state, but, in general, accrued benefits—meaning benefits that have already been earned by an employee or retiree—are protected and cannot be lowered. In many states, reductions to core benefits or creating a new plan design can only apply prospectively, meaning that the change can only impact new workers or future benefit accruals for current workers. As a result of this legal constraint, most pension benefit reforms do not impact existing liability and take time to improve plan finances.

Since 2010, state lawmakers have reduced or eliminated COLAs for active workers and retirees 34 times across 24 states. Next, we look to how these changes were commonly approved with broad bipartisan support, and often as part of a pension reform package that impacted other segments of the population beyond active workers and retirees.

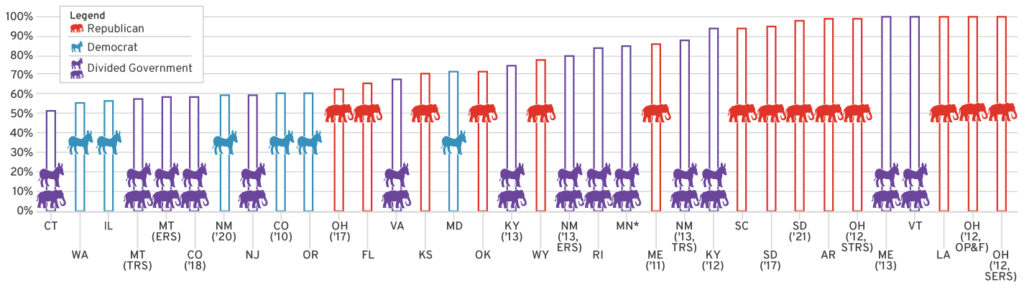

Shared Political Risk, Shared Sacrifice

To further assess the level of cooperation and bipartisanship beyond the determination of which party or parties held power, we collected and analyzed the vote counts for the 34 COLA changes approved by lawmakers. Included as part of Appendix 2 and summarized below in Figure 2, approval margins ranged from 52 percent to 100 percent with an average of 78 percent, and all changes received some level of bipartisan support. Republican-controlled states tended to have wider voter margins than those controlled by Democrats. State governments that were politically divided delivered both the slimmest and widest vote margins in the sample.

Figure 2: COLA Approval Margin by State and Party Control (2010-2022)

We found that half of the COLA reductions were approved with “strong” bipartisan support—defined as those bills receiving affirmative votes from a majority of both the Republican and Democratic caucuses that voted on each bill. It makes sense that strong bipartisanship would be common because bipartisan support makes it harder for one side to launch a political attack on the other based on the reform. It is important that those seeking to reform Social Security similarly come together, as meaningful reform will require both parties.

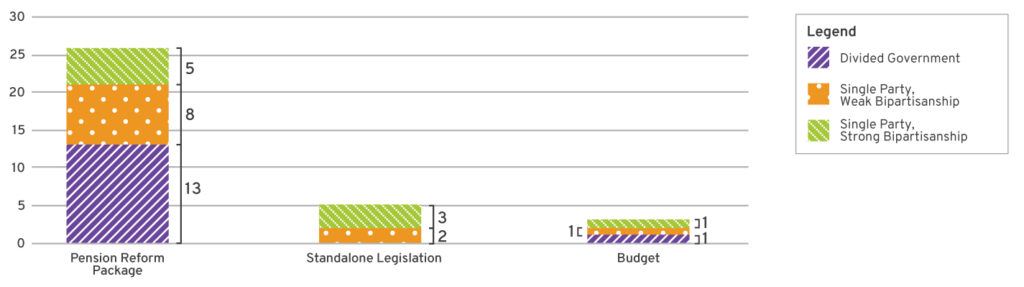

A similar story of mutual aid emerges when looking to COLA reductions and how they were approved. As shown in Figure 3, COLA reductions were most commonly enacted as part of reform packages, meaning the enabling legislation contained changes to other aspects of the pension plan, such as contribution rates or plan design. This suggests that lawmakers were commonly crafting and approving legislative packages that required shared sacrifice among different constituencies.

Figure 3: COLA Changes by Approval Method, Party Control, and Strength of Bipartisanship (2010-2022)

Looking closer at the 26 COLA reductions approved as part of a reform package, 18 occurred in states governed by divided government or—for those approved in states governed by a single party—with strong bipartisan support from both Republicans and Democrats. This suggests that a divided government and a commitment to bipartisan cooperation provides fertile ground to craft impactful entitlement reforms that distribute impacts broadly across different constituencies, while sharing in the resulting political risks. This, once more, reinforces the notion that meaningful reforms to Social Security will require both parties to come together.

Conclusion

Congress faces a daunting challenge to improve the sustainability of Social Security, and many of the policy options available are similar to those used by states to improve funding of public employee pensions throughout the 2010s. This review of the legislative history of state-level reforms finds that they were commonly approved in states governed by Democrats and Republicans alike. It also finds that the most impactful reforms—including those that applied to retiree benefits— were commonly enacted as part of a package requiring shared sacrifice across constituencies and in states where Democrats and Republicans shared the political risk associated with the reform. By following a similar approach in Congress, lawmakers have an opportunity to overcome Social Security’s long-standing reputation of being the third rail of American politics, and to strengthen the system’s ability to support millions of Americans who are retired or disabled.

About the Author

Chris McIsaac is a governance fellow at the R Street Institute.

Appendix 1: Employee Contribution Increases Impacting Active Employees and Approved by State Lawmakers, by Year and Political Party Control. 2010-2022

NOTE: Using pension data from the National Association of Retirement Plan Administrators and state political composition data from the National Conference of State Legislatures, this table summarizes the distribution of 44 active employee contribution increases enacted since 2010 across states fully controlled by Republicans, Democrats, and where control of the Executive and Legislative branches were divided between the two parties. The Nebraska Legislature is nonpartisan and falls under “Divided Government.” States listed twice for the same year include a reference to the plan impacted.

Source: Keith Brainard and Alex Brown, “Significant Reforms to State Retirement Systems,” National Association of State Retirement Administrators, December 2018, pp. 8-97. https://www.nasra.org/files/Spotlight/Significant%20Reforms.pdf; “State Partisan Control,” National Conference of State Legislatures, Nov. 28, 2023. https://www.ncsl.org/about-state-legislatures/state-partisan-composition.

TABLE ACRONYM KEY

ERS—Employees Retirement System

OP&F—Ohio Police & Fire Pension Fund

PERA—Public Employee Retirement Administration

PERS—Public Employees Retirement System

SERS—State Employees Retirement System

TFFR—Teachers’ Fund for Retirement

TRS—Teachers’ Retirement System

Appendix 2: Summary of COLA Reductions Impacting Active Employees and Retirees and Approved by State Lawmakers. 2010-2022

NOTE: Using pension data from the National Association of Retirement Plan Administrators, state political composition data from the National Conference of State Legislatures, analysis of the legislative text, and vote count for each reform, this table summarizes the distribution of 34 COLA reductions by state political party control, the membership group subject to the reduction, the method used to approve the change, and the level of support. “High” bipartisanship means that legislation received affirmative votes from more than half of the Republican and Democratic caucuses. Those with less than half are categorized as “Low.” Changes noted with an asterisk (*) were challenged in court and upheld while those with two asterisks (**) were challenged and struck down. Pension benefits are subject to collective bargaining in Connecticut, and the 2017 vote reflects the House and Senate actions on whether to confirm the agreement between the State of Connecticut and the State Employee Bargaining Agent Coalition. The COLA changes struck down by the Oregon Supreme Court were included in two separate bills but are presented as a single reform for the purpose of this analysis.

Source: “NASRA Issue Brief: Cost-of-Living Adjustments,” National Association of State Retirement Administrators, June 2023, p. 3. https://www.nasra.org/files/Issue Briefs/NASRACOLA Brief.pdf; “State Partisan Control,” National Conference of State Legislatures, Nov. 28, 2023. https://www.ncsl.org/about-state-legislatures/state- partisan-composition.

TABLE ACRONYM KEY

ERB—Educational Retirement Board

ERS—Employees Retirement System

OPERS—Ohio Public Employees Retirement System

OP&F—Ohio Police & Fire Pension Fund

SERS—School Employees Retirement System

TRS—Teachers’ Retirement System