The Great Jobs Deception

Claims of misinformation and disinformation have become commonplace in U.S. politics over the past several years, with what was once a mere technical concern now becoming virtually apocalyptic. As one news outlet has warned: Disinformation poses “an unprecedented threat in 2024.” An equally worried research group proclaimed: “Misinformation is eroding the public’s confidence in democracy.”

But among the political diatribes and distractions, there is at least one place we can turn for solid, verified intelligence, free of mis- and disinformation: U.S. government data. As one prominent data curator has noted, the U.S. government “remains one of the most reliable and widely accepted sources of data reflecting the overall health of our country, our economy, and our democracy… [O]verall, government data remains widely accepted as nonpartisan, transparent, and accurate.”

Some Especially Good News

Case in point: The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). Established in 1884, the BLS recently celebrated its 140th birthday. With this heritage, the BLS obviously knows what it’s doing, and it’s easy to understand—given its richly detailed datasets—why the BLS is widely regarded as one of the world’s foremost data repositories. Indeed, the agency goes to great lengths to ensure that its data is as accurate as possible, and for good reason: it produces some of the United States’ most sensitive and important information, upon which the president, Congress, and federal policymakers rely in order to make critical public policy decisions, and to which news media, businesses, and the general public turn in order to evaluate the effect of those policies.

And lately, the BLS has had some especially good news to report in its prime area of responsibility: U.S. employment data. Since the beginning of 2024, BLS data has been showing a positively booming U.S. jobs market:

- In January, the BLS reported an originally estimated 353,000 new jobs, nearly two times the Dow Jones projection of 185,000 new positions.

- In February, according to the BLS, an initially calculated 275,000 new jobs were created, topping what all but one bank out of 76 major financial institutions had expected.

- And in March, total nonfarm employment was up by a provisionally estimated 303,000, beating even Wall Street’s top forecast of 290,000. It was, in the words of CNN, a “blowout jobs report.”

This over-the-top optimism briefly vanished in April, with just an originally estimated 175,000 new jobs having been added. But May’s initial print was again glowing, at +272,000, beating all forecasts and leading The White House to proclaim: “The great American comeback continues.”

Or so it seemed.

Revisions Up and Down

Unfortunately, by the time June came around, economic tremors already had begun rippling across the landscape. The BLS’ initially announced jobs gains for June fell to 206,000, while July’s new-jobs totals plummeted even further, to an anemic 114,000. And then those tremors became an earthquake: On Aug. 21, the BLS revealed that it had “far overestimated the recent labor market recovery,” saying that the country had added 818,000 fewer jobs from April 2023 to March 2024 than it had previously estimated. This new figure reduced total nonfarm employment growth for the 12-month period by nearly one-third, from the 2.9 million new jobs in the previous monthly estimates to about 2.1 million in the corrected counts—the largest such downward revision in 15 years.

To those who were paying attention, this sharp retrenchment shouldn’t have been a surprise. In a March 2024 state-by-state survey, the Philadelphia Federal Reserve Bank warned—in what turned out to be a very prescient prediction—that U.S. payrolls appeared to be overstated by at least 800,000 workers. But the Philadelphia Fed’s figure, stark as it was, was merely icing on the proverbial cake, as it came on top of the nearly 300,000-job downward adjustment that the BLS had already doled out, month by month.

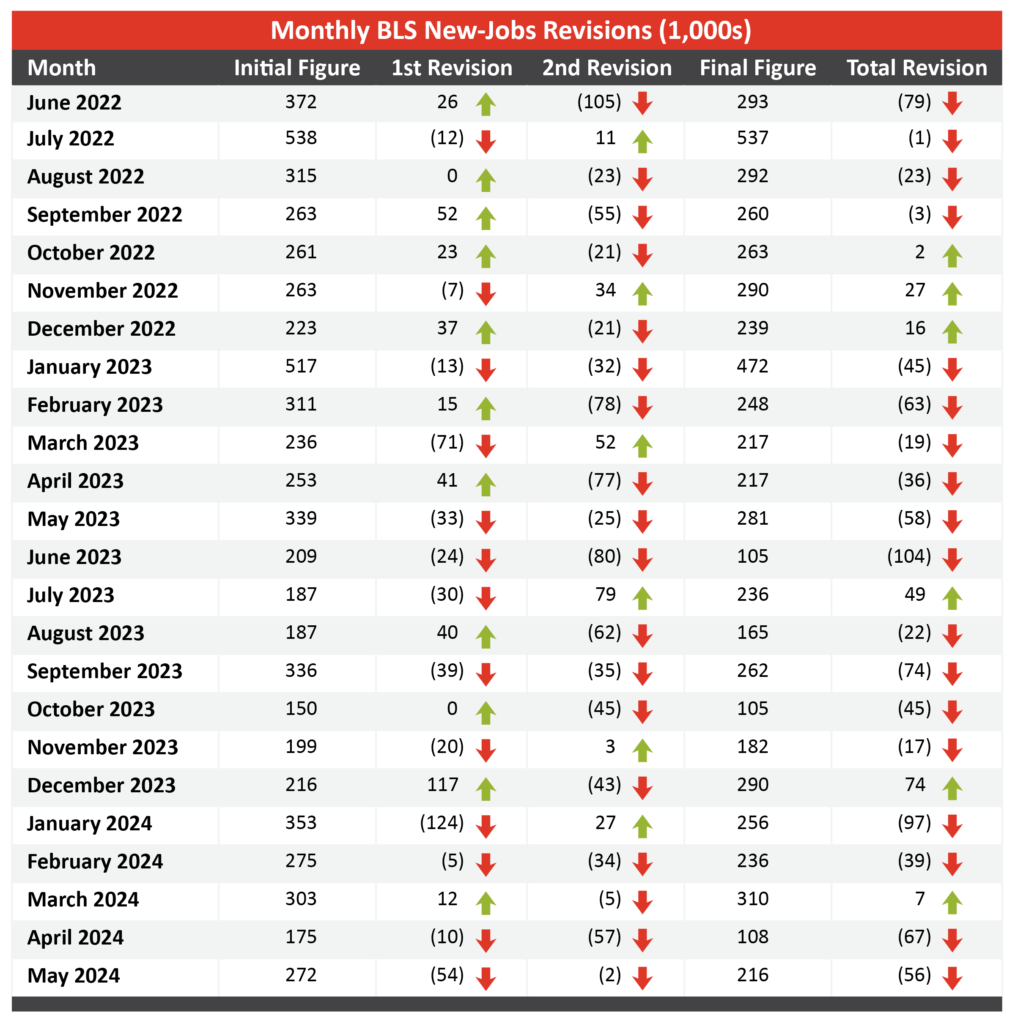

In fact, over the past few years, the BLS has become quite accomplished in downwardly revising its jobs data. Specifically, the BLS releases its employment numbers each month, and then adjusts those numbers in each of the next two months as more data is collected. As one would expect, these adjustments have historically varied—up some months, and down in others. However, for the 24 months from June 2022 to May 2024, the BLS monthly new-jobs totals were downwardly revised 18 times, while being upwardly revised only six times. In terms of magnitude, these monthly downward revisions averaged 47,000 per “down” month while upward revisions averaged only 29,000 per “up” month, for an average 24-month net revision of negative 28,000 per month.

Source: Calculated from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

The Great Jobs Deception

The dynamics of this statistical aberration, barely noticed when viewed superficially, become all too clear as one probes more deeply: When jobs numbers are first reported—and thus receive plenty of mainstream media coverage—they often look rather stunning, to the credit of those in power. But when the jobs numbers in later months are revised—usually substantially downward and hence far less stunning than their forebears—these more accurate figures typically receive no mainstream media airtime whatsoever, making them essentially invisible to the public eye.

Call it “The Great Jobs Deception.”

Are the jobs numbers being manipulated due to politically motivated directives from on high? Although there is no clear evidence one way or the other, the mainstream media and their fact-checking allies strongly deny it. As The Washington Post declares: “A preliminary revision to jobs data is: 1) normal; 2) preliminary; and 3) not a sign that data is being manipulated.” Yet others aren’t so sure. One research report concludes that, while economic reports are routinely revised, “it’s odd how frequently the revisions [have been] worse than the original estimates” over the past few years.

But regardless of the underlying motives or mechanisms, one conclusion is undeniable: Vastly inaccurate numbers like these cannot help but seriously undermine and even distort economic policy decision-making. As is now obvious, the U.S. labor market for the past year has been far weaker than advertised. Had this truth been known earlier, policymakers might have been persuaded to make much different economic decisions than they in fact did—decisions like reducing the destructively high interest rates or enacting tax cuts to stimulate economic growth—that could have saved or created perhaps millions of jobs and diverted the economy from a possible 2025 recession.

Uncomfortable Facts

To be sure, the fact that more than 161 million Americans are employed is a very good thing—an undeniable economic success that is clearly demonstrated by BLS jobs data. But beneath this comfortable blanket of economic appearances lie some very uncomfortable facts largely kept hidden by the Great Jobs Deception: Employment is growing much more slowly than expected, the U.S. economy has been less successful at creating jobs than it seems, millions of people have to hold multiple jobs in order to make ends meet, and millions more can find only part-time work.

These uncomfortable facts don’t deny the economic progress that has been made—and that continues to be made. But they do need to be seen for what they are, and be taken fully into account when making public policy. For unless we pierce this Great Job Deception, then it ultimately may stymie America’s workers in ways that we quite likely do not want to contemplate.