“PR” Should Stand for Proportional Representation, Not Petty Redistricting

America’s system of representative government faces a dire threat. Both major parties are openly racing to redraw congressional maps mid-decade, purely for partisan gain. This gambit undermines the very essence of representative government and ritualizes the process of legislatures—themselves frequently produced by gerrymandered maps—choosing winners instead of the voting public. With more than 7,000 state and federal political districts to draw throughout the country, one solution appears poised to reduce the impact of partisan gerrymandering: proportional representation (PR).

Every 10 years, states redraw their legislative and congressional maps based on new census data in a process known as redistricting. While meant to reflect population changes, this process has increasingly become a tool for partisan advantage. In states where one party controls both the legislature and the governorship, they often draw district lines to maximize their own political power. For example, Democrats in Illinois redrew maps after the 2020 Census in order to squeeze more congressional seats out of already favorable territory. Republicans did the same in North Carolina, crafting maps that turned previously competitive districts into safe GOP seats. This kind of “manufactured representation” locks in political power, disconnecting it from voter preferences and reducing meaningful competition. In the end, voters are left with fewer real choices at the ballot box.

Now, off-cycle from the standard, constitutionally mandated redistricting, many states are looking at drawing the lines once again. The effort began in Republican-led states. At the behest of President Donald J. Trump, Texas Gov. Greg Abbott convened a special session to redraw congressional boundaries in advance of the 2026 midterms. The new proposed map seeks to flip five currently Democratic-held districts. GOP efforts in Ohio, Missouri, and Florida have followed suit.

Not to be outdone, Democrats are looking to respond with their own gerrymandering offensive. In states like California, New York, Maryland, and Illinois, Democrats have proposed their own mid-cycle redistricting plans, much to the chagrin of Republican Vice President JD Vance. Just like that, the parties initiated yet another shameless and unethical contest of political brinksmanship. All told, these efforts to redraw districts mid-cycle for unabashed partisan gain affect more than 40 percent of the U.S. population.

Political scientists often associate this kind of self-dealing electoral system with authoritarian or oligarchic regimes, many of which predate the emergence of genuine democracy in several countries. Instead of candidates competing for votes, parties compete for control over the rules themselves. In the process, voters become mere resources for the parties to divide, and President Abraham Lincoln’s vision of a government “by the people, of the people, [and] for the people” loses meaning.

Fortunately, a policy solution may help mitigate a political problem. In PR, an electoral system used in places like Brazil and most of Europe, multiple winners are selected in each district in proportion to each party’s percentage of the vote. For example, if one party earns 30 percent of the votes in a multi-seat district, then they win approximately 30 percent of the seats. This structure reduces the impact of gerrymandering as larger, multi-seat districts become significantly more difficult to manipulate. While PR is unlikely to end partisan gerrymandering entirely, the net result of a PR electoral system should better reflect a state’s overall partisan makeup—a substantial improvement from the wildly skewed maps we see today.

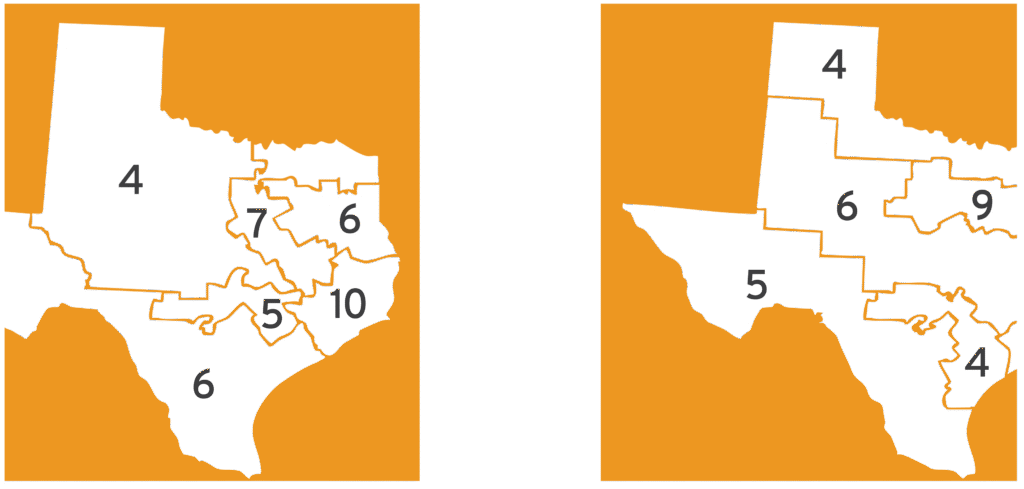

Recent research backs this up: “[E]ven some of the most gerrymandered maps in the nation would produce fair outcomes if existing gerrymandered districts were combined into multimember districts and seats were allocated to parties proportionally.” Look at these potential PR maps for Texas, for example:

The map on the right shows the state’s congressional district plan for the 2022 elections, while the one on the left is based on a proposal submitted by Rep. Chris Turner. The 38 single-member districts are combined into six multi-member districts on both maps.

Each district is displayed with the number of representatives it would elect. Under PR, each party wins roughly the same share of seats as the share of votes it receives in that district. The currently proposed map seeks to further dilute minority voters’ voice by lumping Democratic voters in urban areas into a handful of districts and spreading the rest among majority Republican districts. This surgical election manipulation becomes far more difficult with the large, multi-member districts where urban areas are grouped with their surrounding rural areas and winners determined by proportionality.

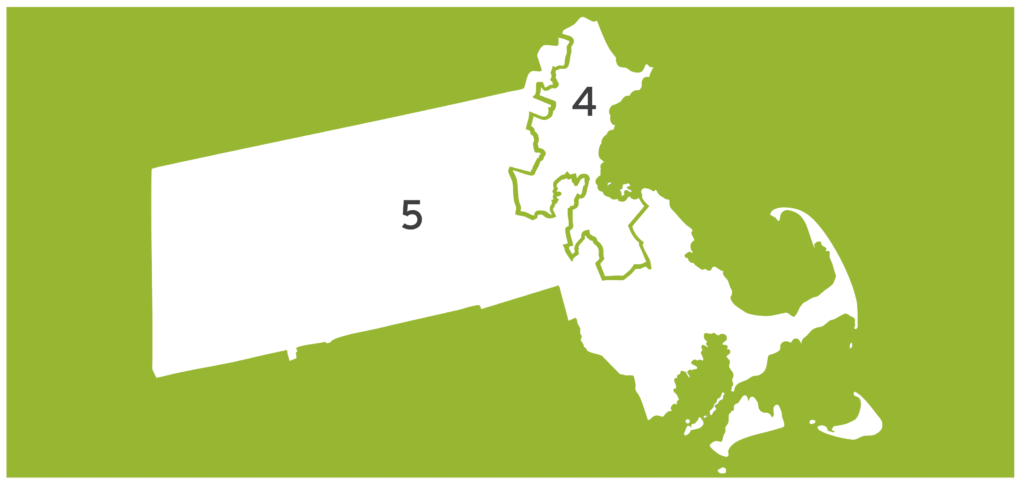

The effect would eliminate the benefits of partisan gerrymandering in either direction. The same exercise was applied to Massachusetts, where Democrats currently control all nine seats despite the fact that more than a third of the population consistently votes Republican. This is not due to gerrymandering; rather, current districting rules and the fact that Republican voters are spread out across the state make a Republican-leaning district impossible to draw.

Again, Republicans become competitive as seats are allocated by voter percentage rather than a winner-takes-all system. For example, in a hypothetical election with similar voting percentages as exist now, Massachusetts Republicans would go from zero to three representatives—almost perfectly in line with the vote share for Republicans in the state. This way, every vote counts and every voter is represented, even those in the minority.

PR won’t magically fix everything, as politicians will still be incentivized to adjust the rules in their favor. However, it implements democracy better than mid-decade gerrymandering wars by shifting power away from legislatures and back to the people—the “only legitimate fountain of power.”