Live and Don’t Learn: 90 Years Later, Washington Repeats Botched Response to Corn Surplus

While the eyes of the nation were on Washington’s shutdown, the hands, heads, and other parts of many farmers were in the field, reaping an extraordinarily bountiful harvest. As anticipated, this year’s grain crop is expected to be one for the record books, pouring cold water on prices and generating despondency and dire headlines. In response, administration officials have promised farmers billions of dollars in cash payments and commodity purchases on top of increased subsidies already secured in the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act.” This is a costly, unnecessary, and altogether wrong response to the current farm economy.

How do we know this? We’ve been here before—and we made the same mistakes then, too.

In its World Agricultural and Demand Estimates for 2025/26, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) predicts that farmers will harvest 90 million acres of corn—the most since 1933—on 98.7 million acres of land—the largest planted area since 1936. Though there’s nearly a century between now and then, Americans today might recognize some things from 1933:

- A trade war and American protectionism had dramatically deepened and exacerbated the Great Depression. The Smoot-Hawley tariff of 1930 is described as “among the most catastrophic acts in congressional history.”

- Farmers had fewer export options following World War I.

- New farm technology (e.g., hybrid corn, greater use of tractors) increased yields, making some farmers more efficient while worsening overproduction.

Today, a similarly unjustified trade war is wreaking havoc on farm exports. And adoption of new technologies—though costly, such as the tools of precision agriculture—are making agribusinesses more efficient. While these similarities might lead to the conclusion that a farm crisis is underway (and while tragic images of the Dust Bowl’s darkest days loom large in our imaginations and agriculture policy), there are more differences between 1933 and 2025 than there are parallels.

Finances: 1933 vs. Today

The farmers of 1933 and today are worlds apart, particularly when it comes to finances. Though apples-to-apples comparisons can be difficult due to changes in how and what data the government tracks, some clear inferences can be made from available information.

| 1933 | Today(ish) |

| The Internal Revenue Service found that the number of “agriculture and related industries” ending the year with losses (3,950) was over 40 percent greater than those ending with profits (2,779). Even at the height of the Great Depression, all other industrial groups had more profitable than unprofitable businesses. | Farm solvency is considered stable, with debts in line with assets. The USDA expects farm operators to reap their second-highest returns of the past decade in 2025. |

| Gross farm income fell by 56 percent between 1929 and 1932. | Median farm household income exceeded all median U.S. household income by 23 percent in 2024 and is expected to rise to $109,515 this year. |

| Farmland values had fallen by 80 percent. | Farmland values are high and continue to rise, creating a major hurdle for young or beginning farmers looking to enter the sector. |

| Forced farm sales were 26.1 per 1,000 in 1931; by 1932, they had soared to 41.7 per 1,000—around 300 percent greater than the 2025 rate. | There were 216 Chapter 12 bankruptcies out of 1.88 million total farms nationwide in 2024; between April 2024 and March 2025, there were 259. (0.14 per 1,000 farms in 1933 terms.) |

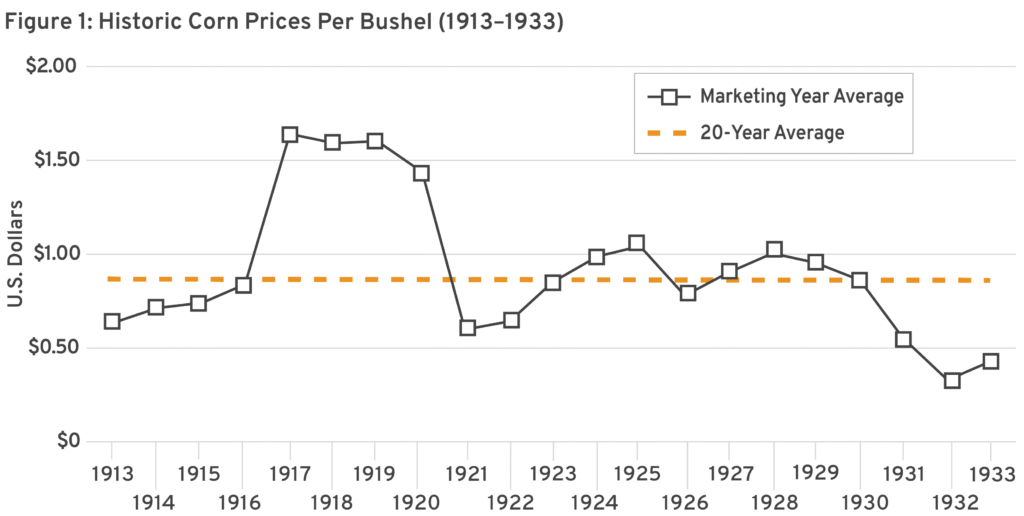

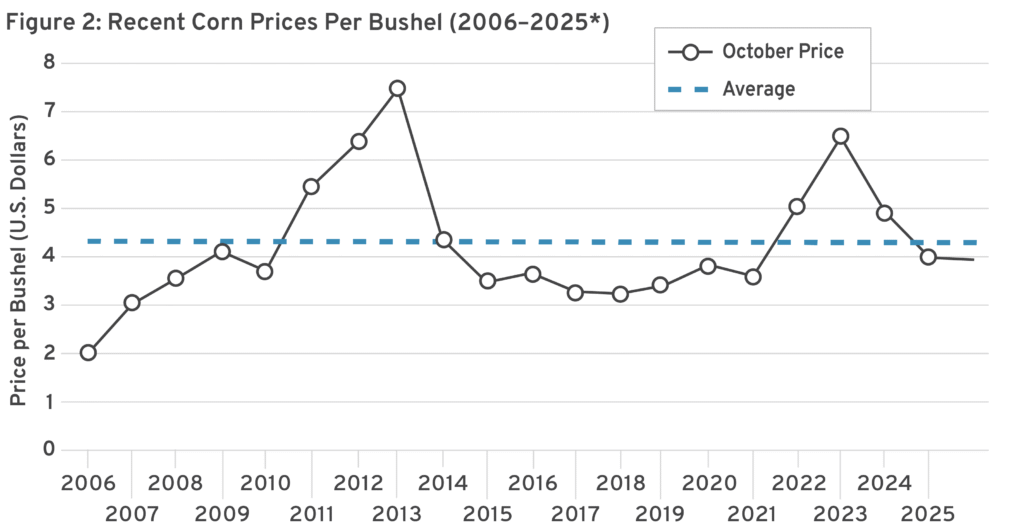

| Never brought in line with new market conditions and reduced consumer demand, record corn production resulted in prices lower than they had been pre-Depression (see Figure 1). | Though corn prices have fallen recently, they are still within spitting distance of the 20-year average (see Figure 2), and futures are strong. |

National Context: 1933 vs. Today

If farm finances of 1933 and today are worlds apart, then the world in which farmers now operate is a universe removed from their predecessors’.

| 1933 | Today(ish) |

| Farming occupied 25 percent of the population. | Farm producers make up only 1 percent of the U.S. population. |

| Of the total U.S. population, 44 percent lived in rural areas. | Just under 25 percent of the total U.S. population lives in rural areas. |

| The agriculture sector contributed 8.3 percent of gross domestic product (GDP). | Agriculture contributes 5.5 percent of GDP. |

Federal Solutions

Despite these profound differences, the response to the 1933 corn glut and today’s corn price concerns are eerily familiar in several key ways:

- Unfair Farm Bill. As part of the New Deal, Washington, D.C. undertook a massive federal intervention in the agriculture industry with the first major “Farm Bill,” the Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA), which gave the secretary of agriculture the authority to dispense payments to farmers who reduced acreage or production. Like today, farmers rightly complained that large farms—often more successful operations with greater assets—benefited more than smaller producers, who were undermined by the program. Others noticed neighbors “farming” the program by removing their less valuable land from production to take advantage of AAA set-aside payments while still reaping income from their fertile fields. Some producers still do this today by planting on low-quality or environmentally sensitive land, knowing taxpayers will guarantee a profit regardless of yield.

- Price Fixing. Corn growers “demand[ed] an emergency program to raise prices” when the long-term legislative plan fell short (just as some agribusinesses are claiming now). In 1933, the USDA’s newly formed Commodity Credit Corporation launched a loan program to restrict the corn supply and artificially boost prices, operating similarly to today’s farm subsidy reference price scheme.

- Commodity Purchases. The Franklin D. Roosevelt administration organized the Federal Surplus Relief Corporation to buy up surplus crops and redistribute them to those in need. Secretary of Agriculture Brooke Rollins has likewise promised that the USDA will purchase millions of bushels of commodities to assist farmers. Though corn prices have recently fallen, they are still within spitting distance of the 20-year average (see Figure 2), and futures are strong.

- Ethanol. Corn growers in Iowa sought a new outlet for excess corn and organized around the “power alcohol movement” with the goal of creating a statewide (and later nationwide) corn ethanol mandate. One farmer stated, “Instead of having our horses eat the corn, we can make the tractor eat it.” A national debate raged, and the mandate proposals ultimately failed in favor of other relief options. Even in 1933, knowledge was widespread that alcohol-blended gasoline had serious drawbacks including “smaller mileage, the need of expensive blends to hold two alien liquids together, [and] the corrosive effect on certain metals.” Environmentally harmful corn ethanol remains a mainstay of farm aid.

Advocates are aggressively seeking year-round approval for higher ethanol blends to spur artificial demand. The head of the Iowa Renewable Fuels Association made the case for greater ethanol consumption, explaining that “[f]armers were very good at overproducing their markets.” Both aching for market options, corn and soy growers also see new aviation and marine fuels as opportunities to expand their business models in lieu of modernizing them.

Worse, in addition to these failed subsidies and the much more resilient economic position of today’s farmers, President Donald J. Trump and his administration have promised billions of dollars in direct payments.

Though the Supreme Court eventually struck down the AAA in 1936, the federal government’s actions in 1933 would lay the foundation for an expensive, expansive, and (so far) permanent federal agriculture apparatus centered on the principle of transferring business-related risks from farmers to taxpayers. As a New Deal architect and USDA administrator of the AAA later lamented, “The problems of another generation were created by the policies of 1933, and absolutely nothing was done to avert what was plainly to be a disaster.”

Nearly four generations later, we are still responding to changes in the farm economy in the same ways, with the AAA at the core of our federal agriculture policies. Sadly for both the farm industry and the taxpayers footing the bills, it seems Washington is stuck in 1933. Despite decades of changes, improved agriculture science and technology, and monumental differences in circumstance, decision-makers still reach for the same failed tools of central planning and handouts.

Historic harvests like this year’s are a testament to American ingenuity and hard work. That same ingenuity should be applied to farm policy reform to prevent making the same mistakes again.