Clearing Homeless Encampments May Reduce Public Disorder, but It Doesn't Keep Communities Safer

More than 770,000 people experience homelessness on any given night in the United States. Of these, almost 20 percent are chronically homeless and over one third are “unsheltered,” meaning they slept in locations not intended for habitation, like cars, bus or train stations, or outdoors. The Trump administration made homelessness an early target of its agenda, issuing an executive order that rewards communities for criminalizing sleeping outdoors and increases involuntary commitment and deployment of federal troops to clear homeless encampments. The administration justifies these crackdowns by linking homelessness to crime and blaming it for reduced public safety.

A robust body of evidence reveals a complex, cyclical relationship between homelessness and crime, suggesting that compared to housed individuals, homeless people are:

- more likely to interact with law enforcement;

- disproportionately charged with survival crimes; and

- more likely to be victims of crime.

However, research is limited on the consequences of criminalizing homelessness and displacing homeless individuals. A recent study published in the Journal of Urban Health begins to fill this gap by evaluating the “spatiotemporal relationship between involuntary displacement events … and short-term changes in nearby crime in a large U.S. metropolitan area.”

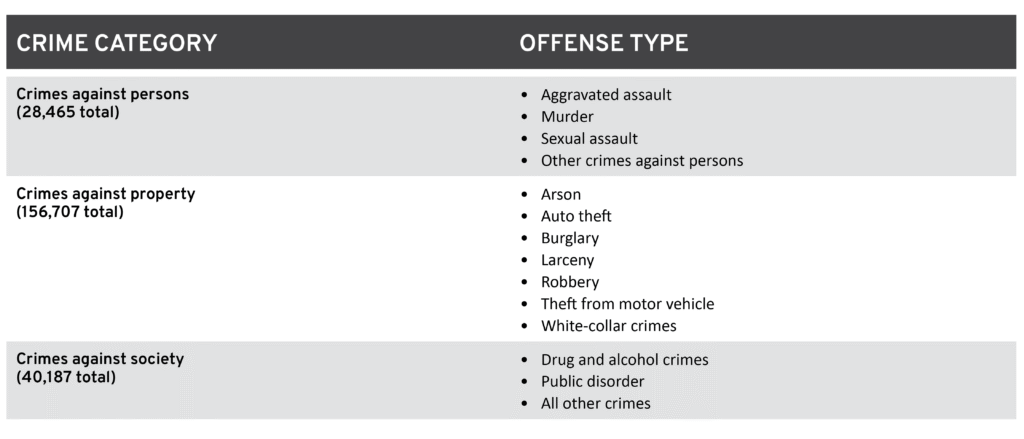

To do this, Pranav Padmanabhan and colleagues examined what happened to neighborhood crime rates in the days and weeks following homeless encampment sweeps in Denver, Colorado, between November 2019 and July 2023. The research team used data on encampment sweeps—including date, time, and encampment location—from the Denver City Council and crime data from the Denver Police Department as recorded in the publicly accessible National Incident-Based Reporting System, dividing it into three categories and 13 offense types. Crimes against property accounted for nearly 60 percent of the 265,011 total crimes, followed by crimes against society (just under 20 percent) and crimes against persons (nearly 11 percent).

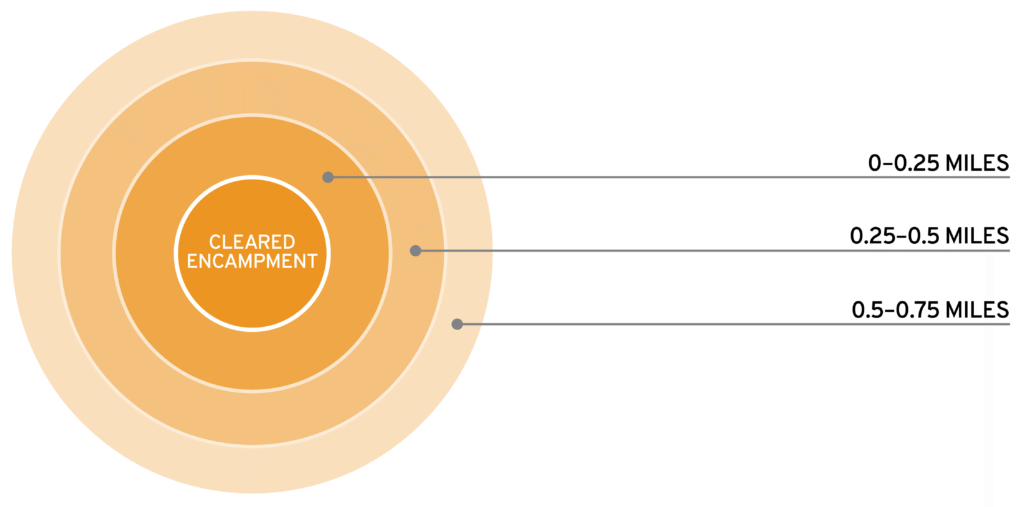

The research team defined their geographic areas of analysis as the “donuts” around cleared encampments at radii of 0 to 0.25 miles, 0.25 to 0.5 miles, and 0.5 to 0.75 miles.

To understand whether the encampment sweeps caused a change in crime, the research team looked at the likelihood that crimes would cluster in these specified areas 7, 14, and 21 days before and after the intervention. The researchers compared these calculations to “expected” crime during the same time and space windows to ensure that any patterns or changes relate to the displacement of homeless individuals.

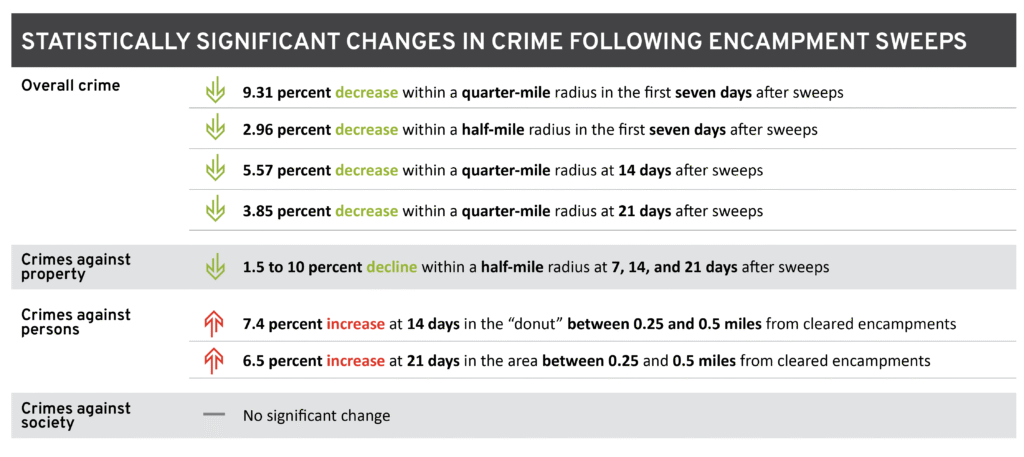

The analysis revealed that overall crime fell modestly in the surrounding areas following encampment sweeps due to large drops in specific crime categories. However, crimes in the category of “crimes against persons” actually increased. See the following table for more detail.

Further breaking down this examination, the authors found that a limited number of crime types were responsible for most of the significant changes. In particular, roughly half (49 to 59 percent) of the decreases in crime at a quarter-mile radius were driven by just two types of crime: auto theft and public disorder (e.g., criminal mischief, loitering, prostitution, harassment, disturbing the peace). Increases were the result of upticks in murder at 0.75 miles from sweeps and by “other crimes against persons” (primarily simple assaults) between 0.25 and 0.5 miles from the cleared encampments.

The Padmanabhan study is the first to assess and quantify the relationship between crime and encampment sweeps in this way. The study does have limitations—especially challenges with crime data—but the authors acknowledge this and use statistically sound methods to account for and mitigate these issues. Another limitation of this study is its relatively narrow time scope. Because the authors only looked at the impact of sweeps on crime rates in the first three weeks following the intervention, they provide no insight as to what happens in the longer term. Similarly, the rather small geographic radii assessed leaves a blind spot around the potential impact of these sweeps on broader surrounding neighborhoods.

Despite these limitations, the study is robust and the authors do an excellent job of contextualizing their findings within the broader literature. For example, they help bring meaning to the increase in crimes against persons by drawing on qualitative research that demonstrates how displacement disrupts known social networks and increases violence between homeless individuals, not violence perpetrated by homeless individuals on random community members.

Thus, this study represents an important and timely contribution to the literature on homelessness and crime, providing a unique perspective on how criminalizing people for sleeping in public impacts not just those targeted, but public safety more broadly. To further the utility of this research, Padmanabhan and colleagues should conduct similar research in a range of cities across the United States.