America’s Prison Numbers Are Dropping—But Don’t Cheer Just Yet

We’re told that America’s shrinking prison population is a sign of progress, and it may very well be. But if we dig a little deeper, we might see it as a warning sign instead. While the United States is on track to cut its prison population 60 percent by 2035, a closer look at the arrest data reveals a more complicated reality—one shaped by evolving enforcement strategies, shifting public behavior, and institutional strain. This reduction may not result from lower crime or thoughtful system modernization alone, though—it’s also likely a product of low case clearance rates, falling arrest rates, depleted police forces, underreporting of crimes, and reduced capacity.

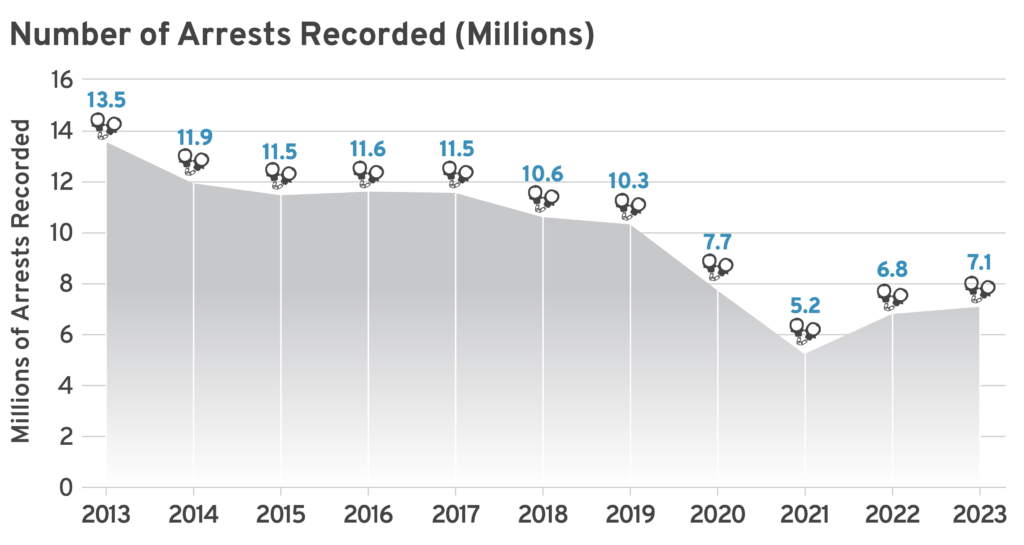

Arrests fell nearly 48 percent between 2013 and 2023. But did crime itself disappear, or was it the ability—or willingness—to make arrests? Departments are understaffed, morale is tanking, and proactive policing has taken a backseat to political risk aversion. Add in eroding public trust and the continuing number of unreported crimes, and it’s clear: We’re not locking up fewer people because we’ve solved more crime—we’re doing it because officers are too overwhelmed, demoralized, or under-resourced to respond effectively. When communities lose faith in the justice system, witnesses go silent, tips dry up, and critical evidence is lost. Overloaded investigators are forced to triage cases for solvability, often prioritizing those with immediate leads while sidelining others indefinitely. Meanwhile, growing backlogs and mounting pressure contribute to burnout, further weakening investigative follow-through. As unsolved crimes accumulate, clearance rates fall—and with them, any real sense of justice or deterrence.

Total arrests dropped from about 13.5 million in 2013 to just over 7.1 million in 2023. The trend was gradual through the mid-2010s before sharply accelerating between 2019 and 2021. Arrests stood at 10.3 million in 2019 but plunged to just 5.2 million—the lowest point of the decade—by 2021. (Both the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s transition to the National Incident Based Reporting System and reduced agency reporting likely contributed.) Although the numbers have slightly rebounded since, we’re still nowhere near pre-pandemic levels. And while violent crime fell by about 3 percent nationally in 2023, over 50 percent of violent crimes and nearly 70 percent of property crimes weren’t even reported to law enforcement. In short, fewer arrests doesn’t always mean fewer crimes—it often means fewer reports, fewer responses, and fewer officers available to act.

Some of the changes are intentional and commendable, particularly in how agencies respond to behavioral health crises. Programs like Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion in Longmont, Colorado cut re-arrests in half by diverting low-level offenders into treatment. In Chicago, Illinois, the Crisis Assistance Response and Engagement program deploys mental health professionals and paramedics alongside police to 911 calls, successfully resolving over 1,300 behavioral health incidents without a single arrest or use of force. In Fairfax County, Virginia, specially trained officers and clinicians respond jointly to mental health calls. In Gloucester, Massachusetts, officers refer individuals struggling with addiction directly to care—no arrest required. And in New York City, the Behavioral Health Emergency Assistance Response Division dispatches EMTs and behavioral health professionals instead of police for certain 911 calls, doubling the likelihood that individuals accept care and sharply reducing arrests—another example of how these models can work well when used to supplement law enforcement.

Unfortunately, not all of the drop in incarceration is due to thoughtful innovation. Two forces are distorting the picture. First is the rise of “depolicing.” Since Ferguson in 2014—and more dramatically post-2020—some departments have retreated from proactive enforcement. Stops, summonses, and public-order arrests have been scaled back—not because they’re ineffective, but because officers worry about liability and backlash. Second, there is a full-blown staffing crisis. Nearly 70 percent of agencies report hiring and retention struggles. Many departments operate with only 91 percent of their authorized strength. That translates to fewer patrols, fewer follow-ups, and fewer arrests, which significantly impacts case clearance rates. In 2023, just 51 percent of homicides and 41 percent of violent crimes were cleared—numbers that reflect both reduced capacity and the ripple effects of public distrust and underreporting.

Meanwhile, the justice system continues to jail staggering numbers of people—often for the wrong reasons. In 2023, over 900,000 individuals were booked into local jails (as opposed to state prisons) for probation or parole violations, more than half a million of which were for so-called “technical” violations like missing curfews, failing to check in, or other non-criminal infractions. These are people incarcerated not for committing new crimes, but for slipping up on conditions. By contrast, only 691,000 people remain behind bars for violent offenses, and just 137,000 for drug-related crimes. This lopsided system prioritizes technical rule-breaking over public safety, straining resources and jail capacity without reducing crime. Even as some policymakers tout declining prison numbers as evidence of success, America still imprisons more people per capita than any other developed country at roughly 580 per 100,000 residents. Cycling thousands through jail for nonviolent missteps while more serious offenses go unsolved isn’t justice—it’s dysfunction.

A drop in incarceration should be the result of deliberate strategy, not unintended collapse. Alternatives for low-level offenders can reduce recidivism, and officers should absolutely have tools beyond handcuffs. But we cannot abandon enforcement altogether. When departments are hollowed out, when crime goes unreported and uninvestigated, when the thin blue line becomes stretched too thin—that’s not progress. It’s a risk. Policymakers would do well to stop measuring success by raw headcounts and focus on rebuilding operational strength instead. Justice only works when the system has the bandwidth to enforce it. That means reinvesting in personnel, backing officers with the tools and training they need, and pairing innovation with real capacity.

Because justice without enforcement isn’t justice—it’s just neglect.