Countries don’t go bankrupt? The 20th century proves otherwise

How risky is sovereign debt?

One memorable answer, “Countries don’t go bankrupt,” is attributed to Walter Wriston, the most prominent banker of his day and the chairman of Citibank from 1967 to 1984. That is right in a narrow legal sense, since a sovereign government cannot be put into bankruptcy. But in the general sense, everybody knows it is disastrously wrong: governments can and do go broke and not pay on their debt.

The 1980s dramatically falsified the Wriston answer. A large number of governments with heavy borrowings from U.S. banks were broke and defaulting. This led to highly-placed fears that the entire American banking system might be insolvent. So Paul Volcker, then Chairman of the Federal Reserve, papered over the crisis by ordering that the banks’ books be cooked and losses postponed. When the crisis broke in 1982, Volcker is reported to have said one Friday evening, “The American banking system might not last until Monday”!

More recently, we have had the European sovereign debt crisis of 2009-2012, which threatened the entire European banking system, imposed huge losses on lenders to the government of Greece-they got 25 cents on the dollar in the 2012 debt restructuring–and raised the possibility of more big losses on the debts of Italy, Spain and Portugal. Of course, the insolvency of the Greek government is still playing out. Demonstrating a typical lack of imagination, European officials had claimed that sovereign defaults in Europe were unthinkable.

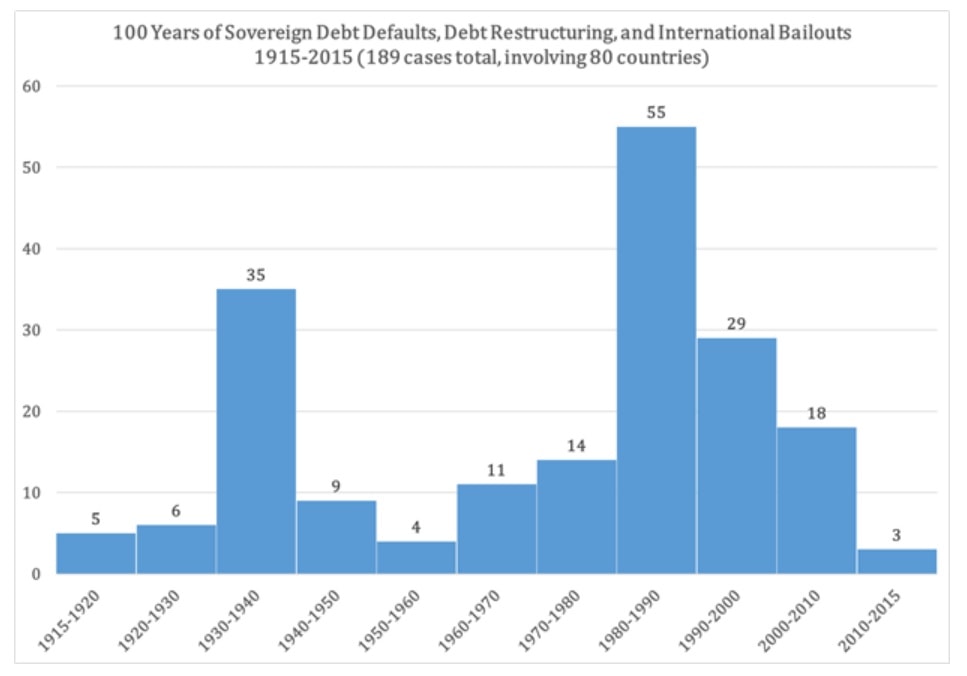

How often do governments go broke and default on their debts? Quite often, it turns out. In the last 100 years, from 1915 to 2015, there were 189 cases of sovereign defaults and restructurings. This involved 80 countries-many were multiple defaulters. In the last 50 years, from 1965 to now, there have been 123 defaults involving 68 countries. In this period, many new sovereign nations had been created, so it gave the possibility, or rather near certainty, or more sovereign defaults.

The following chart displays the 100-year pattern of sovereign defaults by decade. Note the peaks in the 1930s and 1980s, 50 years apart. The 1990s are in third place for this dubious prize, followed by the decade 2000-2010.

Sources: Reinhart, Carmen M., and Kenneth S. Rogoff. 2008. “The Forgotten History of Domestic Debt.” NBER

The defaults on this graph include many Latin American, African and Asian countries, but Europe and North America are also well represented.

The United States government appears three times: when it defaulted on its gold bonds in 1933; when it rejected its obligation to redeem silver certificates for silver in 1968; and when it reneged on its Bretton Woods commitment to redeem dollars for gold in 1971. With this last default, it launched the world into an unprecedented experiment in pure fiat currencies with floating exchange rates-an experiment whose implications we are still discovering. Note that each of the U.S. government’s defaults involved refusing to honor its promise to pay in precious metals. Now its debt is payable only in a paper currency which its central bank earnestly promises to depreciate every year in perpetuity.

To give a flavor of the variety of countries in the sovereign default club, here are the lists for the worst three decades of the last century:

1930s: Austria, Bolivia, Brazil, Bulgaria, Canada (Alberta), Chile, China, Columbia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Germany, Greece, Guatemala, Hungary, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Poland, Romania, Spain, Turkey, United Kingdom, United States, Uruguay, Yugoslavia.

1980s: Angola, Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Central African Republic, Chile, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Egypt, El Salvador, Ghana, Guatemala, Guyana, Honduras, Ivory Coast, Jordan, Liberia, Mexico, Morocco, Mozambique, Myanmar, Nigeria, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Philippines, Poland, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Trinidad and Tobago, Tunisia, Turkey, Uruguay, Venezuela, Yugoslavia, Zambia.

1990s: Algeria, Angola, Antigua and Barbuda, Brazil, Bulgaria, Croatia, Ecuador, Gabon, Iran, Iraq, Kenya, Kuwait, Mongolia, Morocco, Nigeria, Russia, Rwanda, Sierra Leone, Solomon Islands, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Sudan, Thailand, Ukraine, Uruguay, Venezuela.

“The history of government loans is really a history of government defaults,” wrote Max Winkler, in his instructive and cynical book, Foreign Bonds: An Autopsy. History “is replete with instances of governmental defaults,” Winkler observed. “When payment is resumed, the past is easily forgotten and a new borrowing orgy ensues.” That was written in 1933, but is fully up to date.

In all cases, of course, it is a government which is in debt and defaulting, not the country itself. One source of sovereign default is when governments are overthrown and the new regime repudiates the debt of the old one. Notable cases are Russia in 1917 and China in 1949. Another source of default is losing a big war and disappearing as a government, as with Germany, Japan and the Confederate States of America.

But far more common is years of excessive borrowing, whether optimistic or opportunistic, followed by simply being broke and inviting the creditors to join in the losses.

How risky is sovereign debt? Far riskier than good times complacently assume.

As many emerging market countries struggle financially and economically today, are we approaching a new round of sovereign defaults and restructurings? There is certainly no reason to believe that government defaults are out of style. They will occur as long as governments love to spend and love to borrow to keep spending, and as long as lenders have short memories-that is, forever.