How Not to Grow Government

While I was out enjoying a good old fashioned Texas Christmas, Dan Mitchell of the Cato Institute wrote a thoughtful critique of some of my recent articles on the carbon tax that I think warrants a response. In a recent report and accompanying op-ed, I note a somewhat peculiar fact (known as Hauser’s Law, after Kurt Hauser, who first brought it to public attention): since WWII, the amount of tax revenue collected by the federal government has hovered around 19 percent of GDP. This is despite the fact that the tax code has been radically overhauled several times during this period, with top tax rates fluctuating from below 30 percent to above 90 percent.

By some logic, changes to the tax code should result in major shifts in tax revenue. It’s not like we could cut all tax rates to zero and keep them there while expecting the federal government to continue taking in 19 percent of GDP. Therefore, the seeming imperviousness of tax revenues to changes in the tax code is best explained as a political rather than an economic phenomenon. Ultimately, the purpose of taxes is to pay for government spending. When tax revenues fall too far below what is needed to do this, the political pressure for revenue increases grows. By contrast, when tax revenues start to grow beyond what is expected, the political hand of those who want to cut taxes is strengthened. This is how things have gone in the United States for the last 70 years.

Whatever the cause, I argue that Hauser’s Law gives at least some reason to think that a revenue-neutral carbon tax swap would be unlikely to increase taxes over the long term. On this point, however, Mitchell cries foul. Although he concedes the validity of Hauser’s Law in general, he argues that it doesn’t apply to certain types of taxes, like a value added tax (VAT) or carbon tax:

It would be very comforting if politicians in Washington could never seize more than 20 percent of the private sector’s output. Sadly, that’s simply not the case. Just look at Europe, where central governments routinely extract far more than 40 percent of economic output. All that’s required is taxes that target lower- and middle-income taxpayers. That’s happened in Europe because of harsh value-added taxes, punitive payroll taxes, onerous energy taxes, and income taxes that impose very high rates on ordinary people. Needless to say, a carbon tax would be a step in that direction.

Indeed, unbeknownst to Mitchell, my paper originally included a section that compared carbon taxes to a VAT and cited his own proposition that VATs are exempt from Hauser’s Law. Here is the relevant excerpt:

Dan Mitchell, for example, has argued that Hauser’s Law would not apply to the introduction of a consumption tax such as a value added tax (VAT). Since a carbon tax functions as a sort of consumption tax, Mitchell’s argument against a VAT might also apply to a carbon tax as well.

However, that section ultimately ended up on the cutting room floor because I thought it seemed too extraneous (given Mitchell’s response, perhaps I was wrong about that). In any event, the evidence that a VAT grows government is pretty weak. Mitchell points to Europe, where countries have VATs and collect a higher share of GDP in taxes. But, as Reihan Salam has written, this difference has more to do with the greater appetite for government spending by European voters than with the existence of consumption taxes:

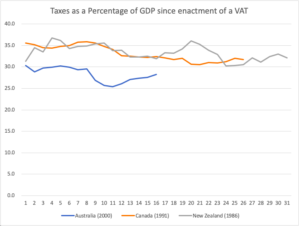

Not all VATs are created equal. Canada has had a federal VAT since 1991. Since then, it has never been increased, and former Conservative Prime Minister Stephen Harper actually cut it in his first term. Australia has its own VAT, established in 2000. A number of Australian politicians, on the right and the left, have tried to hike the VAT, but all have failed. Why have the Canadians and Australians successfully resisted VAT hikes while European taxpayers have not? It’s fairly simple. Like Americans, Canadians and Australians are less favorably disposed to government than, say, Belgians or Swedes.

In fact, since they enacted a VAT, taxes as a share of GDP have remained flat or even fallen in countries like Australia, Canada and New Zealand.

Nevertheless, it should be conceded that Hauser’s Law alone is not an ironclad argument against carbon taxes leading to bigger government. The fact that something hasn’t changed in a long time doesn’t mean that it can’t change. This is why, as noted in my study, a carbon tax is particularly ill-suited as a mechanism for increasing tax revenues. Unlike, say, income or sales taxes, which will grow along with the economy even without an increase in tax rates, carbon tax revenues at a given tax rate are likely to decline over time because the thing they tax (carbon emission) is likely to decrease.

Mitchell notes that even if this is true, it would still be possible to get quite a lot of revenue from taxing emissions—at least in the short term. I accept that point and, in fact, view it as a feature, since it means a carbon tax swap could be used to enact major cuts to existing taxes rather than just tinkering around the edges of the current system. From a limited-government perspective, it might be that worries about the growth of a carbon tax are best addressed by pursuing a swap that includes a higher initial carbon price in order to leave less room for the tax to grow later.

In any event, I’d like to thank Dan Mitchell for his constructive response to my arguments, and am grateful for the opportunity to continue the conversation going forward.