California Does Not Have a Wildfire Insurance Crisis

It’s understandable that wildfire is on the top of mind for California lawmakers this session. Coming on the heels of the 2017 wildfire season that saw $13.2 billion in insured losses, the fires last November that destroyed the town of Paradise have produced $12 billion of losses, the single-costliest blaze in state history.

But while there’s a strong case for California to take action to mitigate its wildfire risk and better prepare for future blazes, some of the responses being pursued in Sacramento risk repeating the mistakes that the State of Florida is just now starting to undo. As the state Assembly appears ready to vote on AB 740, it’s important to remember how starkly California’s wildfire problem differs from Florida’s experience with hurricanes.

Moved by the Assembly to third reading May 28 after unanimous votes by the Assembly’s Appropriations and Insurance committees, AB 740 declares the Legislature’s intent to create what sponsors call the “California Catastrophic Wildfire Victims Fund” (previously, the “Climate Change Catastrophe Compensation Fund”), ostensibly modeled on the Florida Hurricane Catastrophe Fund.

One must say “ostensibly” because precisely how this compensation fund would work remains muddy. Where the Florida Cat Fund provides reinsurance coverage that every property insurer operating in the state must purchase, California’s proposed fund offers scant details regarding both how the fund would be funded and who would receive payouts.

The bill’s most recent draft drops text that explicitly named insurers as one of the fund’s intended funding sources, as well as one of its potential beneficiaries. Where earlier drafts declared the fund would be used “to reimburse insurers, insureds, and local governments for their losses after a wildfire caused by climate change or an electrical corporation,” the most recent version states only that it shall be used “to reimburse victims for their losses after a catastrophic wildfire.”

And while the prior version listed “electrical corporation shareholders, ratepayers, and insurance company shareholders” among the fund’s expected funding sources, the amended version offers only the vague assertion that “the California Catastrophic Wildfire Victims Fund should be funded by multiple entities…”

If the goal of those changes is to move away from any suggestion the proposed fund operate as a part of the state’s insurance market, that’s very much a welcome change. While wildfire losses have been devastating, there is no crisis in California’s homeowners insurance market. If lawmakers want to ensure that insurers continue to provide coverage even as the effects of climate change become more apparent, the most important reforms they could undertake are those that permit risk-based rates.

The same is not necessarily true of California’s utility market, where there’s evidence of significant dislocation. A report issued last month by Gov. Gavin Newsom recommended that the state make changes to its inverse condemnation and strict liability doctrines that hold utilities responsible for disasters arising from their equipment, even in the absence of a finding of negligence. That doctrine was a driver of the $30 billion in liabilities Pacific Gas and Electric Co. incurred from 2017 and 2018 wildfires, ultimately forcing the company and its parent to file for bankruptcy. More recently, S&P Global Ratings downgraded the state’s other two major investor-owned utilities Southern California Edison Co. and San Diego Gas & Electric Co., noting that the companies “will continue to experience catastrophic wildfires because of climate change and without sufficient regulatory protections due to California’s common law application of the legal doctrine of inverse condemnation.”

Creating some form of fund to better manage the utilities’ wildfire exposure could be a sound idea, provided that it was structured, like the California Earthquake Authority, in such a way as to accurately reflect risk. A utility-centered fund also could, like the CEA, take advantage of the deep pools of capital in the global reinsurance market to transfer risk outside of California, rather than forcing the state’s taxpayers to bear that undiversified risk locally. Whether this works in practice will depend quite a bit on how it is implemented.

But there simply isn’t evidence that there is a need for insurance companies to participate in such a fund. In the bill’s preamble, the sponsors note that “the number of homeowners in the wildland urban interface who complained about policy nonrenewal more than tripled from 2010 to 2016.” That’s not surprising. Wildfire risk is correlated by geography and the recent conflagrations have no doubt led some insurers to rethink their concentrations in wildfire-prone areas. There’s only a problem to address if policyholders can’t find anyone to insure that risk.

For that evidence, we need to turn to California’s Fair Access to Insurance Requirements (FAIR) Plan. California is one of 30 states that operate FAIR plans to serve consumers who find they cannot get adequate coverage in the market. Another five states sponsor specialized pools for coastal windstorm risks (“beach plans”). Mississippi, North Carolina and Texas operate both FAIR plans and wind pools, while Florida and Louisiana sponsor state-run insurance companies that operate as both wind pools and FAIR plans.

AB 740’s authors see a crisis brewing with California’s FAIR plan, noting in the bill’s text that over “the last five years, the number of FAIR Plan policies written in brushfire and wildfire areas has increased from 22,397 policies to 33,898 policies, equating to a 51-percent increase.”

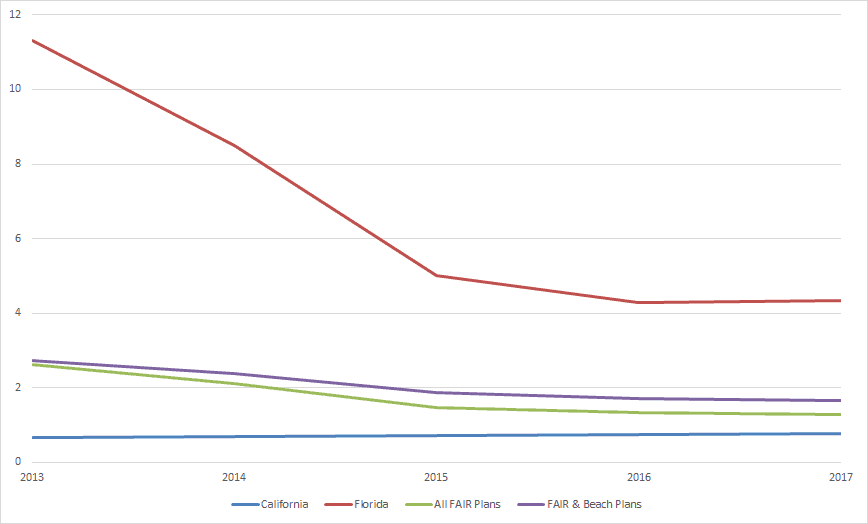

It is true that California’s FAIR Plan has grown in recent years, and wildfire risk considerations are no doubt a major part of that. But it’s important to keep that growth in perspective. According to data from the Property Insurance Plans Service Office (PIPSO), as of 2017, the California FAIR Plan accounted for just 0.77 percent of the market. That’s up from 0.66 percent in 2013, but it still marks California as one of the smaller FAIR plans in the country.

Indeed, the California plan has just a fraction of the market share of Florida’s Citizens Property Insurance Corp., even as the latter’s monumental efforts to shrink to a more reasonable size have been rightly hailed as a smashing success. As the following graphic demonstrates, even as California bucks the general shrinking trend of FAIR and Beach plans nationwide, it has only roughly half the market share of the typical state residual property insurance market.

MARKET SHARE (%) OF STATE RESIDUAL PROPERTY INSURANCE MARKETS

Moreover, to the extent that insurers are showing themselves less eager to extend coverage to properties in the wildland-urban interface, those are market signals we should heed, not try to override. Mitigation can be a powerful tool, and property owners and insurers alike are rightly taking a harder look at expanding zones of defensible space around wildfire-exposed properties and considering an area’s slope, fuel load and access to properties. Significant improvements in the area of mitigation and firefighting could help keep more properties insurable and tamp down the rates that would otherwise be necessary.

But under California’s Proposition 103 system, insurers lack many of the options they would need to incorporate this data. They cannot, for instance, consider changes in the cost of reinsurance in their rate filings. They are limited in how they may use catastrophe models, forcing underwriters to rely on historical loss data even where the evidence is overwhelming that future losses will be far worse. Already limited in their ability to non-renew policies in exposed areas, insurers are now hearing from state lawmakers who want to force them to take all comers.

Accepting the reality of climate change necessarily means grappling with difficult questions of adaptation. Market price signals offer a way to make the pain of such adjustments more gradual and bearable. Recent research by Headwaters Economics finds that nearly half of all new homes are built in the wildfire-prone wildland-urban interface. Rather than seeking to cap insurance rates via regulation or to displace the capital of insurers and reinsurers via a new catastrophe fund, California lawmakers should allow natural market forces to arrest and reverse those settlement patterns.

There is no crisis in California’s homeowners insurance market today. But there will be, if we refuse to hear what price signals are loudly trying to tell us.