The Fed may have triggered the ’08 crash by accident

The gut-wrenching slide of the 2008 stock market crash is unforgettable for those caught in it. In the six weeks from the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy on Sep. 17, the stock market lost over 40 percent of its value.

A quarter of trading days had plunges of 4 percent or more. Investors saw life’s savings dissipate. Traders saw a year’s work and bonus compensation vaporize.

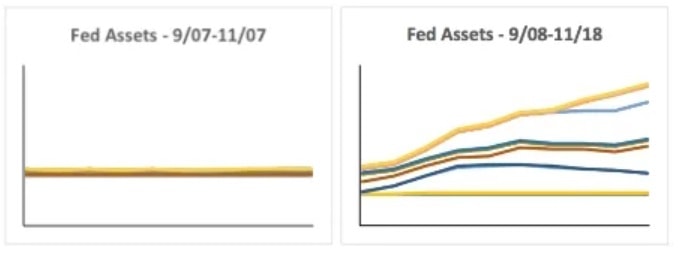

The Federal Reserve and U.S. Treasury, which had been scrambling to cope with the developing financial crisis, accelerated their efforts to a frenetic pace, developing program after program to stem the panic. A chart of the Fed’s balance sheet during this time looks like an EKG gone haywire:

A consequence of the government’s frantic activity was to withdraw nearly a trillion dollars of liquidity from the financial markets over 2008, most of which coincided with the crash. Could the unprecedented policies that squeezed liquidity from the U.S. financial markets inadvertently have triggered the September crash?

Special programs for the crisis

Difficulties in housing and mortgage markets surfaced throughout 2007. In February, sales of existing homes peaked, later to fall 25 percent by September. By June, resale home prices peaked before falling 8 percent by September.

Mortgage foreclosure rates doubled over the course of 2007. Housing market problems led to mortgage market problems, shutting off some banks access to capital.

Responding to the emerging financial crisis in December 2007, the Fed instituted its first programs to maintain credit for financial institutions and provide foreign central banks with dollar funding for their countries’ banks.

March 2008 saw more Fed action. Bear Stearns’ failure and merger needed the Fed’s assumption of questionable assets. Financing problems for primary dealers, the major banks and investment banks licensed to interface directly with the Fed, spurred a program to lend them U.S. Treasury securities to finance operations.

All told, from December 2007 to just before the September 2008 crash, the Fed launched $296 billion of emergency programs to combat the crisis.

Financing these programs was a dilemma for the Fed. Normally, when a central bank sells securities, it receives money out of the regular banking system, which should reduce inflation and/or slow an economy.

Conversely, when a central bank buys securities, it injects money into the banking system, which can speed up an economy and/or increase inflation as banks in turn lend out new money to support economic activity.

Often in a crisis, central banks create money to support emergency lending, but, in the long run, this may be inflationary. The Fed had seen its preferred inflation measure increase from under 2 percent in 2003 to 4 percent in 2008.

A gallon of gasoline was over $4.00. Instead of creating money and risking inflation, the Fed reshuffled its balance sheet, selling Treasury securities to fund emergency programs. The Fed hoped its $296 billion of stimulative emergency lending would offset $290 billion of contractionary securities sales and not affect the banking system or overall economy.

Fed security sales accelerated from $61 billion before March to $229 billion between then and September. Bank lending and investing ground to a halt. From September 2007 to March 2008, bank assets grew 6 percent. From March to September 2008, they fell 1 percent.

The stock market also fell, down 13 percent from December to the crash (measured by the broad-based Wilshire 5000 index).

The 2008 crash

Monday, Sep. 15, 2008 brought bombshell news of Lehman Brothers’ bankruptcy. That day saw a 5-percent decline, followed by a Tuesday bounce of 2 percent accompanying news of AIG’s bailout.

Wednesday saw the market swing sharply down 5 percent, but this was followed by bounces up on Thursday and Friday of 5 percent and 4 percent, respectively. The week of the Lehman bankruptcy and AIG bailout, the stock market actually rose as it had the previous week when rumors swirled of the firms’ demises.

The market slide commenced on Sep. 22 and kept going with a big 8-percent drop on Sep. 29 when Congress initially rejected the bank bailout plan. Final passage of the bailout didn’t help nor did Fed and international central bank guarantees of bank accounts, money market funds or commercial paper.

The market bottomed on Nov. 20, down 41 percent from before Lehman Brothers’ bankruptcy filing.

Rationality isn’t necessarily expected from the stock market, but the 2008 crash’s pattern is curious. The stock market rose as Lehman Brothers and AIG went belly up and plummeted as the world’s most powerful financial authorities introduced program after program to alleviate the crisis. Perhaps there is another explanation.

Financing the Fed during the crisis

The Fed risked running out of resources for emergency lending after selling $290 billion of securities. Its portfolio was down to $485 billion from $719 billion in March, and $200 billion was reserved to finance primary dealers. To provide more resources, Treasury issued debt with proceeds remaining on deposit at the Fed.

Although the procedure is slightly different, the process of Treasury selling debt, obtaining money from the financial markets and leaving it with the Fed has the same contractionary impact as the Fed selling securities directly.

The new Treasury-Fed emergency financing commenced on Sep. 18 with $100 billion in a couple of days. By the following week’s end, $238 billion had been raised. In just seven business days, the Fed and Treasury sold more securities to finance Fed emergency lending than had been done in the previous six months.

To be sure, this funding did not disappear; it was lent to banks through the Fed’s emergency programs, but these distressed banks were filling financial holes and in no position to relend proceeds to recirculate them into the markets and economy.

Even as the Fed began growing its balance sheet in late September and October, banks only slowly increased lending with the crash’s terrible conditions. The Fed and Treasury created a liquidity vacuum where money was withdrawn from the capital markets and economy much faster than it was reinvested with new bank lending.

The brunt of this liquidity vacuum fell on primary dealers transacting directly with the Fed. As the Treasury and Fed issued up to $690 billion of new emergency financing, primary dealers reduced their securities lending by $480 billion by year end.

During this period, there were widespread difficulties with repurchase financing that had lubricated securities markets and funded investment firms.